8

The Diagnostic Anatomy of the Lumbosacral Plexus

Although traumatic lumbosacral plexopathy is uncommon because the pelvic rim protects this structure, the anatomy and diagnosis of these lesions is still quite underreported. This underreporting in the acute trauma patient is likely related to the following issues: (1) Nerve injury is often ignored while more life-threatening injuries are addressed; (2) orthopedic stabilizations preclude proper examination; (3) many physicians are not familiar with lumbosacral plexus anatomy and diagnosis; (4) mild, and even some moderate, lumbosacral plexus lesions can recover during the weeks to months of acute hospitalization and rehabilitation; and (5) once a residual deficit is noted by the physician, the patient is already transferred out of the trauma ward.

Like other lesions of the nervous system, a prerequisite for proper diagnosis and treatment is mastering the anatomy. As with the brachial plexus, one should have a working knowledge of the major branches of the lumbosacral plexus before attempting to tackle its more proximal anatomical relationships. Discussed in previous sections, the femoral and obturator nerves are the major terminal branches of the lumbar plexus, whereas the sciatic nerve is the main product of the sacral plexus. Fortunately, the lumbosacral plexus does not have as many interconnections, or “cross talk” between neural elements, as does the brachial plexus. The spinal nerve contributions to the lumbosacral plexus do, however, split into anterior and posterior divisions prior to forming terminal branches. Therefore, for learning purposes, the lumbosacral plexus may be artificially separated into four regions: the anterior and posterior lumbar (T12-L4) plexus, and the anterior and posterior sacral (L4-S4) plexus.

The Lumbar Plexus

The Lumbar Plexus

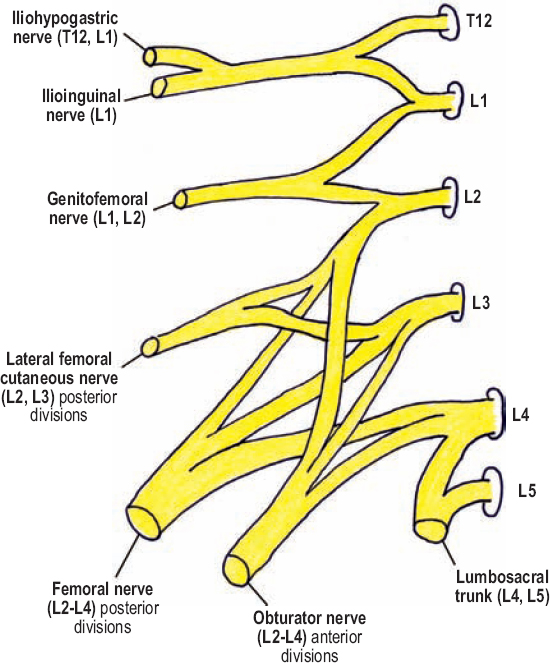

The lumbar plexus is composed of the T12 to L4 ventral rami, which intercommunicate and coalesce to form anterior and posterior divisions in the substance of the psoas major, anterior to the transverse processes (Fig. 8-1). The majority of the lumbar plexus elements are within the psoas muscle. A portion of L4 and all of L5 provide input to the sacral plexus, and not the lumbar plexus.

Overall, terminal branches of the lumbar plexus provide motor and sensory innervation to the lower abdomen, anterior thigh, and medial thigh. Besides a communication with the sacral plexus, there are six branches of significance from the lumbar plexus; two groups of three. The first group consists of major branches to the anterior and medial thigh, while the second group includes minor branches to the groin. Both groups, all six branches, constitute the inguinal complex of nerves. The anatomy and function of these branches have been described in a previous chapter.

Figure 8-1 Lumbar plexus. The lumbar plexus is composed of the T12 to L4 ventral rami, which intercommunicate and coalesce to form anterior and posterior divisions in the substance of the psoas major, anterior to the transverse processes. A portion of L4, and all of L5, provides input to the sacral plexus, and not the lumbar plexus, via the lumbosacral trunk.

The three major branches of the lumbar plexus are the femoral, obturator, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves, which arise from the L2, L3, and L4 spinal nerves. Shortly after exiting their respective foramina, these three spinal nerves bifurcate into anterior and posterior divisions. All anterior divisions coalesce to form the obturator nerve; the posterior divisions join to form the femoral nerve. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve arises from the posterior divisions of L2 and L3 prior to these divisions form the femoral nerve. The most cranial of these three branches, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, emerges from the lateral margin of the psoas major and runs around the abdominal wall to the anterosuperior iliac spine, where it exits the pelvis. The femoral nerve runs down and within the posterior aspect of the psoas major, and emerges from between it and the iliacus muscle in the pelvis, approximately 4 cm proximal to the inguinal ligament, from underneath which it enters the thigh. In contrast to the other branches of the lumbar plexus, the obturator nerve runs along the medial aspect of the psoas muscle, emerges from its medial border in the pelvis, and exits into the thigh via the obturator canal.

The three minor branches to the groin include the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, and genitofemoral nerves. The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves arise from a common trunk, which has contribution from T12 and L1. This trunk bifurcates within the substance of the psoas major, yielding the more superior (cranial) iliohypogastric nerve (T12,L1) and the more caudal ilioinguinal nerve (only L1), both of which perforate the lateral margin of the psoas major and loop around the abdominal wall toward the inguinal ligament. After being formed by its L1 and L2 spinal nerve contributions, the genitofemoral nerve, alternatively, perforates the anterior margin of the psoas major, medial to the psoas minor, and runs caudally on this muscle next to the ureter. The ventral rami of T12 to L2, which contribute to the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, and genitofemoral nerves, do not divide into anterior and posterior divisions in the psoas major; this added complexity only occurs in the lower, more major branches of the lumbar plexus.

The lumbosacral trunk, which is made up of a portion of L4 and all of L5 (ventral rami), passes caudally over the sacral ala, adjacent to the sacroiliac joint, to join the sacral plexus. The lumbosacral trunk provides much of the motor and sensory innervation to the common peroneal division of the sciatic nerve. The L4 spinal nerve is known as the furcal nerve. Furcal means “forked,” and refers to the three proximal divisions of the L4 spinal nerve (ventral ramus only): contribution to the lumbosacral trunk, anterior division to the obturator nerve, and posterior division to the femoral nerve.

A few, small motor branches also arise directly from the lumbar plexus. For example, the ventral rami of L1 to L4 provide motor innervation to the quadratus lumborum, and sometimes to the psoas major. Additionally, one or two proximal branches off the femoral nerve also provide motor innervation to the psoas major. When present, the psoas minor is innervated by proximal twigs off the L1 and L2 spinal nerves.

A few, small motor branches also arise directly from the lumbar plexus. For example, the ventral rami of L1 to L4 provide motor innervation to the quadratus lumborum, and sometimes to the psoas major. Additionally, one or two proximal branches off the femoral nerve also provide motor innervation to the psoas major. When present, the psoas minor is innervated by proximal twigs off the L1 and L2 spinal nerves.

The Sacral Plexus

The Sacral Plexus

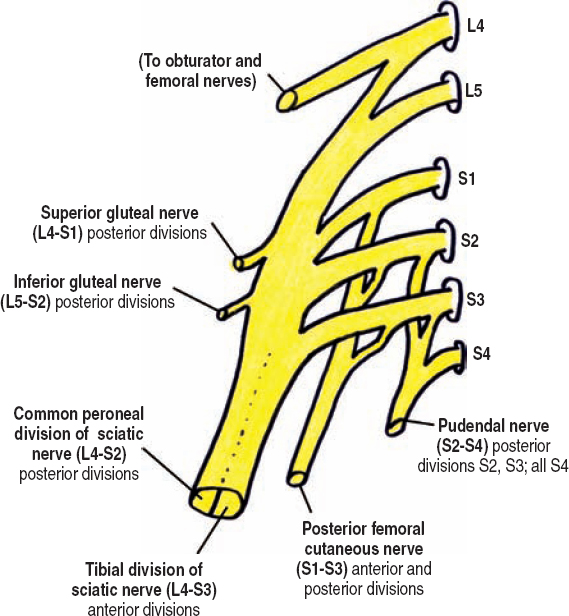

The sacral plexus is a triangular-shaped complex of neural elements over the inner surface of the sacroiliac joint (Fig. 8-2). It is made from the ventral rami of the L4 to S4 spinal nerves, of which S1 to S4 emerge from the ventral sacral foramina. The lumbosacral trunk, made of L4 and L5 contributions to the sacral plexus, passes medial to the obturator nerve, into the lesser pelvis where it joins the sacral plexus. Similar to the lower lumbar plexus, ventral rami contributions to the sacral plexus bifurcate into anterior and posterior divisions prior to forming terminal branches. Nearly all the anterior divisions coalesce to form the tibial division of the sciatic nerve (L4-S3). The posterior divisions, except S3 and S4, form the common peroneal division of the sciatic nerve (L4-S2). The fact that the common peroneal nerve is made of one less division makes sense, considering it is the smaller of the two sciatic nerve components.

In addition to the sciatic nerve, there are several other branches that originate from the sacral plexus, which may be categorized based on whether they originate from the anterior divisions, posterior divisions, or both.

Branches from the Anterior Divisions

Two branches arise from the anterior divisions of the sacral plexus. The first is the nerve to the quadratus femoris and inferior gemelli, which arises from the anterior divisions of L4, L5, and S1. The second is the nerve to the obturator internus and superior gemelli, which originates from the anterior divisions of L5, S1, and S2. Note that both of these nerves arise from three divisions, however, their origins are shifted by one spinal nerve level. These two nerves provide motor innervation to their named muscles, which together help externally rotate the thigh. Test this movement with the patient seated, legs dangling, while stabilizing the knee with one hand, instruct the patient to resist when you try to pull the lower leg inward (Fig. 8-3).

Figure 8-2 Sacral plexus. The sacral plexus is a triangle-shaped complex of neural elements over the inner surface of the sacroiliac joint. It is made from the ventral rami of the L4 to S4 spinal nerves, of which S1 to S4 emerge from the ventral sacral foramina. All spinal nerve contributions, except S4, bifurcate into anterior and posterior divisions (not shown) prior to forming terminal branches.

Branches from the Posterior Divisions

There are also two branches from the posterior divisions of the sacral plexus, each similarly originating from three divisions and being shifted by one spinal nerve level. The superior gluteal nerve arises from the posterior divisions of L4, L5, and S1, and the inferior gluteal nerve from the posterior divisions of L5, S1, and S2.

The superior gluteal nerve exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen above the pyriformis muscle and spreads to innervate the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fascia latae muscles. These three muscles act in conjunction to abduct the thigh. Abduction of an extended thigh (at the hip) is from gluteus medius and minimus contraction. Abduction of a flexed thigh is mostly secondary to tensor fascia latae contraction. To test gluteus thigh abduction, the patient should abduct the thigh against resistance while supine or standing (Fig. 8-4). Normally, you should not be able to break thigh abduction. Alternatively, to test tensor fascia latae thigh abduction the patient should spread the legs while seated on an examining bench (Fig. 8-5).

Figure 8-3 External rotation of the flexed thigh (L4-S2) assessment: Test this movement with the patient seated, legs dangling. While stabilizing the knee with one hand, instruct the patient to resist when you pull the lower leg inward.

Figure 8-4 Gluteus medius and minimus thigh abduction (L4-S1) assessment: The patient should abduct an extended thigh against resistance while standing (shown) or supine. Normally, you should not be able to break thigh abduction.

The inferior gluteal nerve innervates the gluteus maximus muscle, which extends the thigh with some assistance from the hamstrings. The gluteus maximus may be tested in isolation with the patient either prone or standing (Fig. 8-6). Start with the leg flexed at the knee to eliminate hamstring substitution, and then instruct the patient to extend the thigh at the hip. Of note, it is normal for this range of motion to be limited. This is because the rectus femoris muscle is placed stretched when the thigh is extended. The buttock may be simultaneously palpated to ascertain muscle contraction.

A Branch from Both the Anterior and Posterior Divisions

The posterior femoral cutaneous nerve originates from both the anterior and posterior divisions of S1 to S3. More specifically, it arises from the posterior divisions of S1 and S2, and the anterior divisions of S2 and S3. The posterior femoral cutaneous nerve is also called the lesser sciatic nerve, and runs medial and parallel to the sciatic nerve in the buttock region. As both of these “sciatic” nerves pass distally, the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve becomes more superficial and medial, running just lateral to the ischial tuberosity at the lower margin of the gluteus maximus. At the gluteal fold, it pierces the fascia to become subcutaneous. Its sensory territory includes the lower buttock, posterior midline of the thigh, and most of the popliteal region (Fig. 8-7). In some individuals, this territory may extend distally to include some posterior calf. Considering their close anatomical relationship, the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve may be damaged along with the proximal sciatic nerve following buttock trauma.

Damage to the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve causes numbness in the lower buttock and posterior thigh, which may be confused with an S2 radiculopathy. These two processes may be differentiated because, in addition to radiating low back pain, patients with an S2 radiculopathy usually have mild gastrocnemius weakness and a depressed ankle reflex.

Figure 8-5 Tensor fascia latae thigh abduction (L4-S1) assessment: Have the patient spread the legs while seated on an examining bench. By flexing the hip, contribution to thigh abduction from the gluteal muscles is minimized.

Figure 8-6 Thigh extension (L5-S2) assessment: The gluteus maximus may be tested in isolation with the patient either standing (shown) or prone. Start with the leg flexed at the knee to eliminate hamstring substitution, and then instruct the patient to extend the thigh at the hip. The buttock may be simultaneously palpated to ascertain muscle contraction.

Figure 8-7 Sensory territory of the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve (posterior view). This nerve’s sensory territory includes the posterior midline of the thigh, and most of the popliteal region. In some individuals, its territory may extend distally to include some posterior calf.

There are additional, proximal branches from the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve that pierce the fascia and become subcutaneous at the gluteal fold. The more lateral branches are called the inferior cluneal nerves and provide sensation to the inferior and lateral buttock. The medial branch is called the inferior pudendal nerve, which provides sensation to the scrotum or labia.

Other Branches

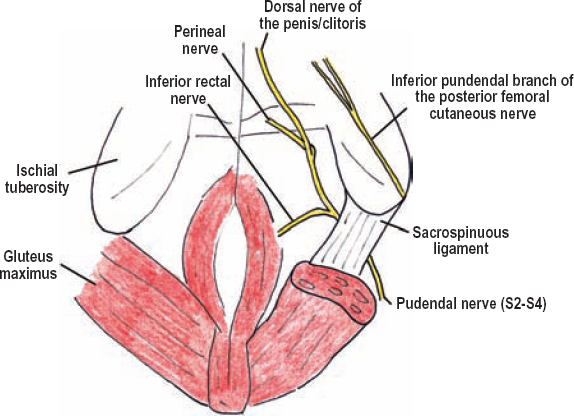

The pudendal nerve primarily originates from S4, with supplemental input from the anterior divisions of both the S2 and S3 spinal nerves. The pudendal nerve exits the medial aspect of the greater sciatic foramen, turns to enter the lesser sciatic foramen, and makes its way to the pudendal (Alcock’s) canal, which is deep to the sacrospinous ligament (Fig. 8-8). There are three named branches from the pudendal nerve: (1) the inferior rectal nerve, which innervates the external anal sphincter and skin around the anus, (2) the perineal nerve (the continuation of the pudendal nerve after the inferior rectal nerve branch), which runs with the perineal artery to innervate the posterior scrotum or labia, erectile tissue, and the external urethral sphincter, and (3) the dorsal nerve to the penis or clitoris.

Small branches off the posterior surface of the S1 and S2 ventral rami merge to become the nerve to the pyriformis. The pyriformis muscle assists in external rotation of the thigh when flexed (Fig. 8-3).

As with the brachial plexus, there is variability in the spinal nerve input to the lumbosacral plexus. When T12 provides a large contribution, and S3 only a minimal one, or none at all, the lumbosacral plexus is considered prefixed. In contrast, when T12 provides no input, L1 only a small contribution, and S4 significant input to the plexus (besides the pudendal nerve), the lumbosacral plexus is considered postfixed. Furthermore, each branch from the lumbosacral plexus may be composed of additional, or fewer, spinal nerve components than usual.

As with the brachial plexus, there is variability in the spinal nerve input to the lumbosacral plexus. When T12 provides a large contribution, and S3 only a minimal one, or none at all, the lumbosacral plexus is considered prefixed. In contrast, when T12 provides no input, L1 only a small contribution, and S4 significant input to the plexus (besides the pudendal nerve), the lumbosacral plexus is considered postfixed. Furthermore, each branch from the lumbosacral plexus may be composed of additional, or fewer, spinal nerve components than usual.

Figure 8-8 Branches of the pudendal nerve (caudal view). The pudendal nerve exits the medial aspect of the greater sciatic foramen, then turns to enter the lesser sciatic foramen, making its way into the pudendal (Alcock’s) canal deep to the sacrospinous ligament. There are three branches of the pudendal nerve: the inferior rectal nerve, perineal nerve (the continuation of the pudendal nerves after the inferior rectal nerve branch), and the dorsal nerve to the penis or clitoris.

Diagnostic Approach to the Lumbosacral Plexus

Diagnostic Approach to the Lumbosacral Plexus

When the pattern of weakness and sensory loss in a lower extremity appears to affect more than one major nerve a lumbosacral plexus lesion should be suspected. The concurrent involvement of certain other plexal branches (i.e., gluteal nerves, posterior cutaneous nerve to the thigh, and/or pudendal nerve) helps confirm this. However, besides these nerves, few other testable nerve branches arise from the lumbosacral plexus, making lesion localization within the lumbosacral plexus difficult, and sometimes impossible. The patient’s history, risk factors, co-existing injuries, and mechanism of injury provide important information that should be used to help differentiate proximal branch injuries versus true plexal damage. History of a pelvic tumor, radiation, trauma, or complicated delivery is especially pertinent (see below). Aside from motor and sensory deficits found on examination, sympathetic loss, manifesting as erythematous, dry, warm skin, can also be seen with plexal injuries that involve the sympathetic nerves. Radiographic investigations, including plain X-rays, myelography, and CT (computerized tomography) myelography are used to confirm fractures, pseudomeningoceles, hematomas, and foreign bodies, all of which can aid lesion localization. Additionally, electromyography can be quite useful in differentiating plexopathies, proximal mononeuropathies, and radiculopathies.

Lumbar plexus injuries manifest with thigh flexion, thigh adduction, and leg extension weakness. Sensory changes can occur in the lower abdomen (iliohypogastric nerve), groin (ilioinguinal nerve), genitalia/femoral triangle (genitofemoral nerve), lateral thigh (lateral femoral cutaneous nerve), anterior thigh (femoral nerve), medial thigh (femoral and obturator nerves), and medial leg down to the arch of the foot (saphenous nerve). Lumbar or sacral plexus injuries can be partial or complete. The most noticeable deficits with lumbar plexus damage are quadriceps weakness/wasting and anterior thigh sensory loss. For this reason, many patients with lumbar plexus damage are misdiagnosed as having only a femoral neuropathy. Therefore, it is important to remember that for patients with complete or partial femoral palsies, one should check for adductor weakness (obturator nerve) and sensory loss on the anterolateral thigh (lateral femoral cutaneous nerve) to help exclude a lumbar plexus injury.

Sacral plexus damage can cause sciatic nerve motor and sensory loss, sensory loss to the posterior midline thigh (posterior femoral cutaneous nerve), motor loss of the gluteal muscles (superior and inferior gluteal nerves), as well as sexual, bladder, and bowel dysfunction (pudendal nerve, autonomic nervous system). Analogous to the femoral nerve in lumbar plexus injuries, sciatic nerve palsy is the predominant finding in sacral injury patients. Therefore, patients with suspected sciatic palsies, especially those with leg flexion weakness (hamstrings), should be fully evaluated for a sacral plexus injury. Check the patient’s sensation in the posterior thigh (posterior femoral cutaneous nerve), thigh abduction and extension (superior and inferior gluteal nerves, respectively), and perianal sensation (pudendal nerve damage). Sacral plexus damage is difficult to differentiate from concurrent palsies of the sciatic, inferior gluteal, and posterior cutaneous nerves, all of which can be simultaneously injured distal to the plexus where they together exit the greater sciatic foramen below the pyriformis muscle. The superior gluteal and pudendal nerves exit the pelvis away from these other three nerves; therefore, thigh abduction weakness and perineal sensory loss would be important findings that implicate sacral plexus injury.

Focal damage to the lumbosacral trunk is particularly difficult to diagnose and requires further comment. L5 radiculopathy, lumbosacral trunk damage, sciatic nerve injury predominantly involving the common peroneal division, and common peroneal nerve palsy may all have similar clinical findings, namely a foot drop. A lumbosacral trunk lesion may be differentiated from sciatic or common peroneal palsies because it often causes weakness in the posterior tibialis as well as other more proximal muscles, including the gluteals (thigh extension and abduction). Differentiating an L5 radiculopathy from a lumbosacral trunk lesion is often not possible clinically. Imaging (to rule out nerve root compression) and electrical testing (to document paraspinal muscle denervation) help confirm an L5 radiculopathy. A fracture/dislocation of the ipsilateral sacroiliac joint on CT or X-ray may point toward lumbosacral trunk damage in trauma patients with a foot drop.

Lower sacral plexus (S3-S5) damage causes peri-neal/peri-anal sensory loss, decreased anal sphincter tone, loss of an anal reflex, and loss of a bulbocavernosus reflex. Test the anal reflex (anal wink) by scratching the skin near the anus and observing the sphincter’s reflexive contraction. Afferents for this reflex are carried by S5 and efferents by S3-S5. Test the bulbocavernosus reflex by briefly flicking the glans penis while with your other hand you palpate any bulbocavernosus muscle contraction behind the scrotum. Afferents for this reflex are carried by S3 and efferents by S3-S5.

Sympathetic fibers destined for the lower extremity originate from the upper lumbar spinal nerves and enter the sympathetic trunk to be subsequently distributed to the peripheral nerves in the lumbosacral plexus. Therefore, lumbosacral plexus and peripheral nerve (e.g., sciatic nerve) lesions can cause sympathetic abnormalities in the lower extremity (e.g., a warm, dry foot). In contrast, lower lumbar and sacral radiculopathies do not because the injury or compression is proximal to where the sympathetic nerves join the plexus.

Spinal Nerve Dermatomes and Myotomes

Being able to rule out a peripheral nerve problem in patients with presumed spinal radiculopathies is very important, especially in surgical candidates without clear-cut back and radicular pain. In this section, a summary of the respective dermatomes and myotomes for the L1 to S1 spinal nerves is provided. Overall, L2, L3, and L4 radiculopathies should be differentiated from femoral neuropathies, L5 radiculopathy from common peroneal nerve injury, and S1 radiculopathy from a tibial nerve lesion.

The L1 spinal nerve provides sensation to the hypogastric area, groin, and base of the penis/mons pubis. Muscle weakness does not occur. Pain within the L1 dermatome is, however, usually non-neural in origin. Local processes, including hernias or lymphadenitis, are often the reason for the pain. Non-neural problems should not cause sensory loss, so if numbness is present, one should strongly consider nerve injury, especially if the patient had previous surgery. Ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral neuropathies, as well as upper lumbar plexus lesions, are all in the differential diagnosis of a suspected L1 radiculopathy.

The L2 spinal nerve provides sensation to the anterior thigh and motor innervation to the iliopsoas muscles. Therefore, although both a femoral neuropathy and L2 radiculopathy may cause anterior thigh pain, numbness, or paresthesias, their motor deficits are different: femoral neuropathies cause quadriceps weakness; L2 radiculopathies cause iliopsoas weakness. Alternatively, if the motor exam is normal and spine imaging does not reveal a compressive lesion, anterolateral sensory loss on the thigh is probably meralgia paresthetica. For meralgia paresthetica the patellar reflex would be normal.

The L3 spinal nerve provides sensation to the lower anterior thigh and knee region, along with motor innervation to the quadriceps and thigh adductors. Therefore, the main differential of an L3 radiculopathy is once again a femoral neuropathy. For patients with a femoral neuropathy, however, adductor strength would be normal, which is not the case for a severe L3 radiculopathy. spine imaging and/or electrodiagnostic testing are required to differentiate an L3 radiculopathy from a lumbar plexus lesion.

The L4 spinal nerve carries sensation to the medial leg, in the distribution of the saphenous nerve. It provides substantial motor innervation to the quadriceps via the femoral nerve and the thigh adductors via the obturator nerve. It also provides motor innervation to the anterior tibialis via the common peroneal nerve. To differentiate a femoral neuropathy from a L4 radiculopathy one should check for thigh adductor weakness and foot dorsiflexion weakness, which would only be present with a radiculopathy.

The L5 spinal nerve provides sensation to the anterolateral shin, and dorsum of the foot. It also innervates all the muscles innervated by the common peroneal nerve. Therefore, a common peroneal neuropathy should be ruled out in all L5 radiculopathy patients. Fortunately, the L5 nerve root provides motor innervation to other muscles besides those innervated by the common peroneal nerve, including the posterior tibialis and glutei. Therefore, foot inversion (posterior tibialis) should be normal for patients with common peroneal lesions. Of note, many patients with a L5 radiculopathy have depressed or absent ankle jerks. This is because large herniated discs at L4/5 can also partially affect the S1 nerve root.

The S1 spinal nerve provides sensation to the lateral aspect (via the sural nerve) and sole (via the plantar nerves) of the foot. Motor innervation includes the muscles of foot plantar flexion, as well as all the foot intrinsics. This pattern of sensory and motor loss closely mimics that of the sciatic nerve’s tibial division, and/or the tibial nerve itself. The S1 nerve root, however, also innervates the gluteal muscles via the superior and inferior gluteal nerves. Therefore, in addition to the presence of low back and radicular pain, gluteal weakness helps confirm a S1 radiculopathy. Furthermore, the posterior tibialis (L4, L5; foot inversion) does not receive S1 input, and therefore would be spared with a S1 radiculopathy, but not necessarily for a sciatic or tibial injury. A tibial neuropathy can be differentiated from both a S1 radiculopathy and a proximal sciatic lesion because it would spare both the gluteal muscles and the more proximally innervated hamstrings.

Processes Affecting the Lumbosacral Plexus

Processes Affecting the Lumbosacral Plexus

As with the brachial plexus, damage to the lumbosacral plexus can be categorized as structural or nonstructural. Structural etiologies include tumors, hemorrhage, postsurgical, obstetric/gynecologic, traumatic, and injections. Nonstructural causes include lumbosacral amyotrophic neuralgia, radiation, vasculitis, diabetes, infection, and hereditary pressure palsies. Some etiologies are discussed further.

Trauma

Traumatic lumbosacral plexopathy is usually partial and is most commonly caused by high-speed deceleration (i.e., motor vehicle) accidents where the pelvis or hip is fractured/dislocated. In fact, about one quarter of all pelvic fractures are associated with nerve damage, plexal or otherwise. Most traumatic lumbosacral plexus injuries are postganglionic from stretch or traction; however, sacroiliac joint fractures or dislocations may cause spinal nerve avulsion. These avulsions may occur in or out of the spinal canal. As in the cervical region, myelography and MR imaging assists in the diagnosis of nerve avulsion by documenting pseudomeningoceles. Considering the proximity of the lumbosacral trunk to the sacroiliac joint, it may be selectively damaged with fracture/dislocations in this area. Because the lumbosacral trunk carries many fibers destined for the common peroneal division of the sciatic nerve, these patients present with a foot drop.

Traumatic or iatrogenic injury of the lumbosacral plexus may be divided into four diagnostic zones, with most patients having more then one zone either completely or partially involved. Zone 1 involves the anterior divisions of the lumbar plexus (the obturator nerve, medial thigh). Zone 2 involves the posterior divisions of the lumbar plexus (the femoral and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves, anterior, medial, and lateral thigh/leg). Zone 3 refers to the anterior divisions of the sacral plexus (the tibial division of the sciatic nerve). Zone 4 involves the posterior divisions of the sacral plexus (the common peroneal division of the sciatic nerve as well as the superior and inferior gluteal nerves). The utility of this zone-based categorization of lumbosacral injuries may prove to be limited because most injuries do not follow these convenient boundaries. Preliminary data reveals that trauma most frequently involves either the sacral plexus alone, or the complete lumbosacral plexus. Isolated, traumatic lumbar plexus injuries are quite rare.

Retroperitoneal Hemorrhage

Patients with hemophilia or taking anticoagulation medications may have spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhages. Patients with normal clotting may also have retroperitoneal bleeds following trauma, retroperitoneal surgery, or groin catheterization. Hemorrhage may be confined to the psoas muscle, iliacus muscle, or abdominal wall; larger hemorrhages may involve all three of these areas. A psoas muscle hemorrhage would selectively compress the lumbar plexus. These patients have acute, often severe, back pain radiating to their groin and anterior thigh. Weakness occurs in the quadriceps, iliopsoas, and occasionally the thigh adductors. Severe pain may limit the accuracy of the neurological assessment. Sensory loss in a lumbar plexus distribution, mostly in the groin and anterior thigh, may occur. Hip movement is painful and patients are often most comfortable with the thigh flexed at the hip.

More-extensive hemorrhages affecting the lumbar plexus can tract caudally to also compress the lumbosacral trunk and sacral plexus. Alternatively, focal hemorrhages in the iliacus muscle (i.e., iliacus compartment), which typically can occur following groin catheterization, may selectively compress the femoral nerve.

Lumbosacral Plexitis (Amyotrophic Neuralgia)

This clinical ailment of uncertain etiology affects both lumbosacral plexus as it does the brachial plexus. Patients present with an acute or subacute onset of proximal lower-extremity pain, often radiating down the anteromedial or posterior thigh, sometimes down into the lower leg. The pain is quite severe and limits motor assessment. Days to weeks later (on average 1 week), weakness appears in the distribution of the pain. Paresthesias may also occur. Plexal involvement is usually partial, affecting either multiple plexal branches, or just one (e.g., the femoral nerve). Over time, the pain and weakness slowly resolve, with many patients having close to complete resolution after several months.

Proximal Diabetic Neuropathy

Weakness is the predominant manifestation of proximal diabetic neuropathy (diabetic amyotrophy). It usually causes thigh flexion, thigh adduction, thigh abduction, and leg extension weakness (femoral, obturator, and gluteal nerves). Atrophy of the proximal thigh and hip girdle may occur. Although pain can be severe, concentrated in the back, groin, or anteromedial thigh, many patients have only mild or no pain. As with idiopathic lumbosacral plexitis, weakness and pain from proximal diabetic neuropathy usually resolves in several months (3 to 18). Residual stiffness and weakness can remain, however. Acute diabetic neuropathies only affecting the femoral nerve are quite rare; most patients actually have other, perhaps subtle, involvement of the lumbar plexus. The etiology of proximal diabetic neuropathy may be epineurial microvasculitis.

Two distinct types of proximal diabetic neuropathy can occur. The first type is descriptively called proximal asymmetric neuropathy. Patients with this type have abrupt onset of unilateral weakness as well as a severe amount of inguinal and thigh pain. Patients report trouble ambulating because of knee buckling. Diabetic patients with this type usually do not have peripheral (stocking-glove) neuropathy, and are not usually insulin dependent. A history of recent weight loss, curiously, is often present.

The second type is called proximal symmetrical neuropathy, and often occurs in insulin dependent diabetics with a history of peripheral (stocking-glove) neuropathy. The onset of weakness is slow, manifesting over days to weeks. The weakness is bilateral, although still asymmetrical. Pain can occur, but is also slow in onset.

Neoplastic and Radiation Damage

Pelvic tumors may cause plexopathy, and in these patients, severe pain, not weakness, is the primary complaint. The initial presentation is usually an insidious onset of back or pelvic pain that radiates to the thigh or leg. Weakness and/or numbness can occur, but these deficits are usually minimal. If the tumor involves the most caudal fibers of the sacral plexus bilaterally, incontinence can also occur. Primary tumors affecting the lumbosacral plexus include colorectal, uterine, prostate, and ovarian. Secondary, or metastatic, tumors involving the lumbosacral plexus include breast, sarcoma, lymphoma, testicular, and thyroid. Malignant invasion of the lumbosacral plexus has four patterns: lumbosacral involvement only, sacral plexus involvement only, complete ipsilateral lumbosacral plexus involvement, and bilateral lower sacral involvement.

Pelvic, or lower paraspinal, radiation therapy may cause lumbosacral plexopathy. Radiation doses greater than 5000 rads are usually required, with symptoms appearing slowly, on average 5 years later (range 1 to 30 years). Radiation plexopathy is usually painless, or with minimal pain, which is a key finding that helps differentiate radiation plexopathy from recurrent tumor, which is usually painful. Radiation plexopathy presents with an insidious onset of weakness. The rate of progression and completeness of the lesion are variable. The majority of cases are bilateral. Numbness and paresthesias may occur. Weakness usually stabilizes only after it is already profound. Improvement is unlikely. Myokymic discharges on needle electromyography occur in radiation plexopathy, being a useful way to help exclude recurrent tumor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree