3

The Diagnostic Anatomy of the Radial Nerve

The radial nerve is the “great extensor” of the upper arm, innervating nearly all the extensor movements in the upper extremity. Although its chief importance is muscular innervation, the radial nerve also carries sensory information from a significant portion of the posterior arm, forearm, and hand.

More so than for any other nerve, a complete understanding of radial nerve palsies and entrapment syndromes requires mastery of its three-dimensional (3D) anatomy. This is because, in contrast to the median and ulnar nerves, whose paths are relatively linear and uncomplicated, the radial nerve spirals its way down the arm, back and forth between the flexor and extensor compartments. Most importantly, one must understand the location, origins, and insertions of the triceps and supinator muscles, which are intimately related to the radial nerve.

Anatomical Course

Anatomical Course

The Axilla

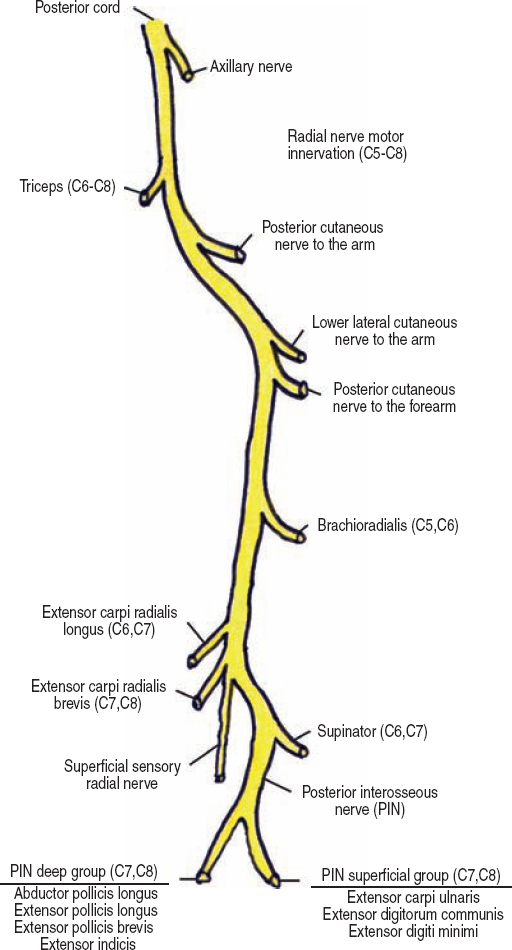

After giving off the thoracodorsal and axillary nerve branches, the posterior cord of the brachial plexus continues distally as the radial nerve. The radial nerve is the largest terminal branch from the brachial plexus. It is made up of the C5 to C8 nerve roots. The radial nerve is located posterior to the axillary artery in the axilla. This relationship with the axillary artery is in contrast to the median and ulnar nerves, both of which are located more anteriorly.

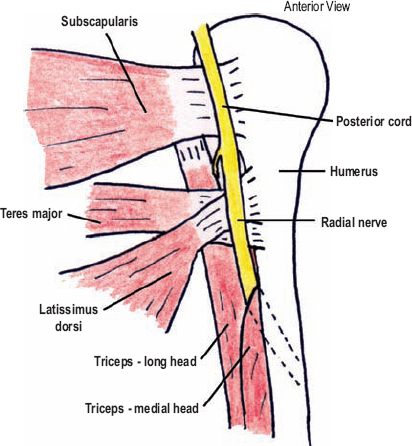

In the distal axilla and proximal arm, the radial nerve drifts further posterior to the brachial artery. As with the other brachial plexus branches, the radial nerve is located, deep to the pectoralis major and minor, when it exits the axilla, the radial nerve lies superficial to three sequential muscles, which together constitute the posterior axillobrachial border (from proximal to distal): (1) the sub-scapularis muscle that inserts into the humeral head, (2) the latissimus dorsi tendon that inserts into both the head and surgical neck of the humerus, and shortly thereafter, (3) the teres major that inserts into the surgical neck of the humerus (Fig. 3-1). In the proximal upper arm, the radial nerve continues distally by running on the anterior surface of the long head of the triceps, a muscle that originates in the axilla from the lateral scapula.

Figure 3-1 Radial nerve in the distal axilla. The radial nerve lies superficial to three sequential muscles as it exits the axilla (from proximal to distal): the subscapularis muscle that inserts into the humeral head; the latissimus dorsi tendon that inserts into both the head and surgical neck of the humerus; and the teres major that inserts into the surgical neck of the humerus. The radial nerve enters the arm upon (superficial to) the long head of the triceps, and almost immediately dives into the cleft between the long and medial triceps’ heads. Within this cleft, the nerve runs toward the most proximal portion of the spiral groove.

In approximately 10% of the population, the radial nerve also carries fibers from the T1 spinal nerve.

In approximately 10% of the population, the radial nerve also carries fibers from the T1 spinal nerve.

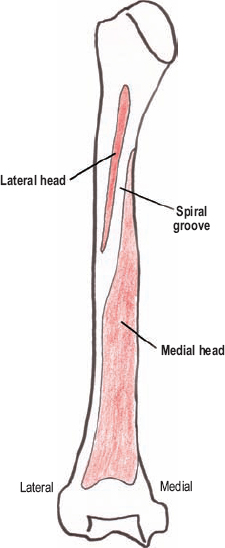

The Axilla to the Spiral Groove

The triceps has three heads—the long, medial, and lateral—all of which share a common insertion upon the olecranon, and act in unison to extend the forearm. Their names are derived from their respective origins. The long head is so named because it goes all the way from the scapula, high in the axilla, down to the olecranon. It has a relatively straight course between these two points. The medial head of the triceps originates along the medial and posterior humeral shaft, remains anterior and medial to the long head of the triceps, and posterior and medial to the humerus. The lateral head originates along the lateral shaft of the humerus, and remains lateral to both the long head of the triceps and the humerus. These origins of the lateral and medial heads of the triceps run parallel along the humerus in a spiral fashion (Fig. 3-2). This spiral insertion begins posteromedially, and curves distally by running posterior, then lateral, along the humerus. The thin, bare area of bone between the origins of the lateral and medial heads of the triceps is called the spiral groove.

After entering the arm on (superficial to) the long head of the triceps, the radial nerve almost immediately dives into the cleft between the long and medial triceps’ heads (Fig. 3-1). The brachial profunda artery runs with the radial nerve in this cleft. Together they course posteriorly and medially toward the most proximal portion of the spiral groove. Once reaching the spiral groove, the radial nerve continues distally by running posterior and lateral to the humerus between the origins of the lateral and medial heads of the triceps (i.e., along the spiral groove). The nerve remains in contact with the humerus and is covered by the lateral head of the triceps until it pierces the lateral intermuscular septum, about halfway down the arm, just distal to the deltoid’s insertion into the humerus.

Figure 3-2 Origin of medial and lateral heads of the triceps on the humerus (posterior view). The origins of these heads of the triceps run parallel along the humerus in a spiral fashion. This spiral begins posteromedially, and curves distally by running posterior, then lateral, along the humerus.

The Spiral Groove to the Supinator Muscle

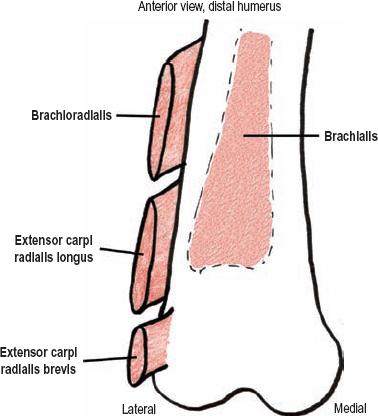

Just distal to the spiral groove, the radial nerve enters the flexor compartment by piercing the lateral intermuscular septum. At this point the radial nerve is quite immobile and superficial, and therefore prone to injury. Once in the flexor compartment, from mid-arm to antecubital fossa, the radial nerve runs underneath the following three muscles, which sequentially arcade over the nerve: (1) the brachioradialis, (2) the extensor carpi radialis longus, and (3) the extensor carpi radialis brevis (Fig. 3-3). This anatomical arrangement has been referred to as the radial tunnel. The last muscle, the extensor carpi radialis brevis, is unique in that it originates underneath the nerve, but subsequently loops over it; an anatomical arrangement that can predispose to nerve irritation. In this region, the brachialis muscle lies medial and posterior to the radial nerve and the lateral epicondyle of the humerus is posterior to the radial nerve.

Figure 3-3 Upon entering the flexor compartment at mid-arm level, the radial nerve runs underneath three muscles, which sequentially arcade over the nerve. This anatomical arrangement has been referred to as the radial tunnel. The origins of these muscles are depicted.

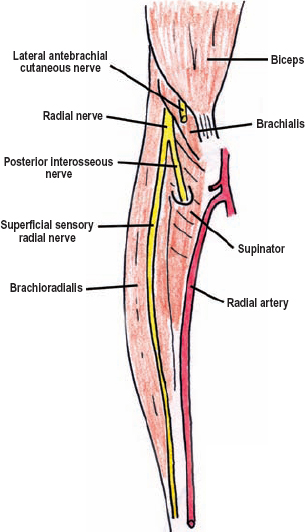

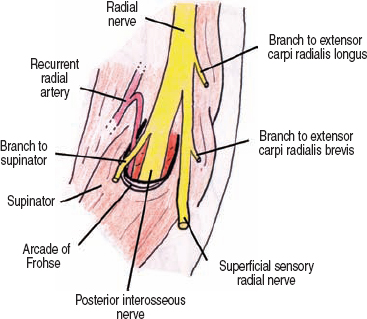

Distal to the elbow joint, the radial nerve lies on the most proximal portion of the supinator muscle’s deep head (see below). In this area, the radial nerve bifurcates into the posterior interosseous and superficial sensory radial nerves. The location of this bifurcation is quite variable, and can be either proximal or distal to the lateral epicondyle.

Allow your right arm to hang at your side in anatomical position (supinated). Grasp your right forearm with your left hand, just distal to the lateral epicondyle, so that the web space between your thumb and index finger is on the lateral border of the arm with your fingertips pointed in the direction of the elbow joint. Your left hand is the supinator muscle. The supinator muscle originates from the anterior, lateral, and posterior aspects of the radial bone (your palm), and attaches more proximally to the anterior and lateral portions of the lateral epicondyle of the humerus (thumb tip), as well as to the most superior portion of the ulna’s posterior surface (fingertips). As the forearm pronates with an extended elbow, the supinator muscle is stretched as the radius crosses anterior to the ulna. With subsequent supinator contraction, and resultant shortening of this muscle, the arm supinates.

This muscle has both a deep and superficial head. If you had two left hands and put the second one on top of the first, it would replicate the anatomical relationship between these two heads. The radial nerve has a characteristic relationship to the supinator muscle. The superficial head of this muscle forms a “pocket,” like on a pair of jeans, into which the posterior interosseous nerve descends. The edge of this pocket can be fibrous and is termed the arcade of Frohse. The superficial sensory radial nerve remains superficial to the superficial head of the supinator.

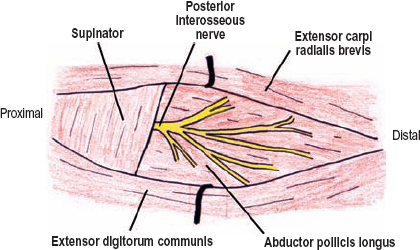

The Posterior Interosseous Nerve

The posterior interosseous nerve carries no cutaneous sensation; therefore, it is a “pure” motor nerve. It dives into the supinator pocket, deep to the arcade of Frohse. The recurrent radial artery, a branch of the radial artery, enters the supinator’s “pocket” with the posterior interosseous nerve. Once between the two heads of the supinator muscle, the posterior interosseous nerve travels laterally around the head of the radius, entering the extensor compartment of the forearm. In some people, the deep head of the supinator muscle is quite thin, or occasionally even absent, and therefore the posterior interosseous nerve may actually lie directly on the radius. After emerging from between the two heads of the supinator muscle in the extensor compartment of the forearm, the posterior interosseous nerve lies deep to the extensor digitorum communis, and superficial to the abductor pollicis longus. It then ramifies into a large number of unnamed branches, which are often called the cauda equina of the arm (Fig. 3-4). While remaining underneath the extensor digitorum communis muscle, the posterior interosseous nerve runs in sequence over the abductor pollicis longus, the extensor pollicis longus, and the extensor pollicis brevis (the three radial nerve-innervated thumb muscles). Distally, along the bottom third of the forearm, some of the branches of the posterior interosseous nerve are quite deep, lying directly on (posterior to) the interosseous membrane. Here, the posterior interosseous artery, a branch from the interosseous communis artery, which stems from the ulnar artery, joins them.

The Superficial Sensory Radial Nerve

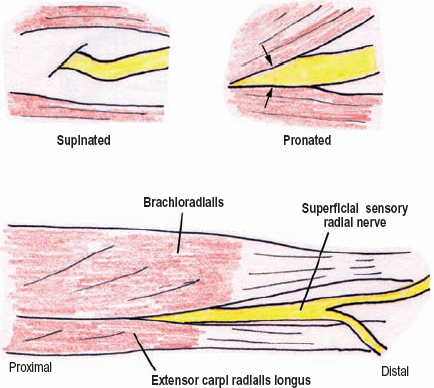

This terminal division of the radial nerve remains superficial to the supinator muscle, but deep to the brachioradialis muscle. In fact, it remains underneath the brachioradialis muscle until approximately two thirds of the way down the forearm (Fig. 3-5), running on the posterior (deep) muscular bed of the extensor carpi radialis longus. More distally, but still proximal to the wrist, the tendons of these two muscles form and separate, with the brachioradialis tendon more anterior and the extensor carpi radialis longus tendon more posterior. Between this “fork” in the tendons, and on the lateral edge of the radius, the superficial sensory radial nerve pierces the antebrachial fascia to become subcutaneous. This nerve then passes to the dorsal aspect of the wrist, and branches upon the dorsolateral aspect of the hand, superficial to the extensor retinaculum. The superficial sensory radial nerve usually has four or more terminal branches.

Figure 3-4 Once emerging from between the two heads of the supinator muscle in the extensor compartment of the dorsal forearm, the posterior interosseous nerve lies deep to the extensor digitorum communis, and superficial to the abductor pollicis longus. It then ramifies into a large number of unnamed branches, which are often called the cauda equina of the arm.

Figure 3-5 The superficial sensory radial nerve in the distal forearm. This terminal branch of the radial nerve passes distally between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis muscles.

Motor Innervation and Testing

Motor Innervation and Testing

As the great extensor of the upper extremity, the radial nerve innervates four groups of muscles: the triceps group (one muscle, three heads), the lateral epicondyle group (four muscles), the posterior interosseous nerve-superficial group (three muscles), and the posterior interosseous nerve-deep group (four muscles) (Fig. 3-6).

The Triceps Group

The long head of the triceps is the first muscle innervated by the radial nerve. Fibers to this muscle arise very proximally at the axillobrachial junction. The next muscle to be innervated is the medial triceps head, followed by the lateral triceps head. This pattern of innervation is logical considering the sequence of contact between the radial nerve and the three heads of the triceps. The main branches to the medial and lateral heads originate proximal to where the radial nerve enters the spiral groove. However, additional branches to these two muscles arise directly from the radial nerve in the spiral groove. To test the triceps (C6-C8), have the patient start by placing the upper arm parallel to the ground, which eliminates the effect of gravity. With the forearm half-extended, support the limb at the elbow and instruct the patient to extend the forearm fully against resistance (Fig. 3-7).

Figure 3-6 Motor innervation of the radial nerve. The radial nerve innervates muscles that extend the forearm, hand, and fingers. It also supinates and flexes the forearm.

In 50% of the population, the lateral head of the triceps is innervated prior to the medial head.

In 50% of the population, the lateral head of the triceps is innervated prior to the medial head.

Figure 3-7 Triceps muscle (C6-C8) assessment: Have the patient place the upper arm parallel to the ground, which eliminates the effect of gravity. Starting with the forearm half-extended, support the limb at the elbow and instruct the patient to fully extend the forearm against resistance.

The Lateral Epicondyle Group

All branches to the brachioradialis (C5, C6) originate from the radial nerve proximal to the lateral epicondyle. To test this muscle, have the patient flex the forearm against resistance with the forearm halfway between pronation and supination (Fig. 3-8). With contraction, the brachioradialis muscle becomes prominent in the lateral antecubital fossa, where it can be observed and palpated.

The two more distal muscles, the extensor carpi radialis longus (C6, C7) and brevis (C7, C8) are assessed together by having the patient extend and abduct (bend radially) the hand against resistance (Fig. 3-9), while you stabilize the distal forearm with your other hand. With the arm pronated, these muscle bellies can be seen lateral to the brachioradialis. Most branches to the extensor carpi radialis longus originate from the radial nerve above the lateral epicondyle, while branches to the extensor carpi radialis brevis originate below the lateral epicondyle.

Figure 3-8 Brachioradialis (C5, C6) assessment: The patient flexes at the elbow with the forearm halfway between pronation and supination. With contraction, the brachioradialis muscle becomes prominent in the lateral antecubital fossa, where it can be observed and palpated.

Figure 3-9 Extensor carpi radialis longus (C6, C7) and brevis (C7, C8) assessment: These two muscles are assessed together by having the patient extend and abduct (bend radially) the hand against resistance. With the arm pronated, contraction of these muscles can be seen lateral to the brachioradialis.

Distal to the lateral epicondyle in the proximal forearm, the posterior interosseous nerve innervates the supinator (C6, C7). Branches destined for this muscle originate from the posterior interosseous nerve prior to it passing into the muscle. The supinator muscle supinates the forearm. Although the biceps brachii is also a strong forearm supinator, it can be placed at a mechanical disadvantage by extending the forearm. Therefore, to isolate the supinator it should be tested with the forearm extended (Fig. 3-10).

Because the radial nerve’s point of bifurcation into the posterior interosseous and superficial sensory radial nerves is variable, the axons destined for the extensor carpi radialis brevis can originate from the radial nerve proper, or from one of these two distal branches. The brachialis muscle receives some innervation from the radial nerve in this region (in addition to its main innervation from the musculocutaneous nerve). However, this innervation to the brachialis is usually not enough to flex the arm in the presence of musculocutaneous nerve palsy.

Because the radial nerve’s point of bifurcation into the posterior interosseous and superficial sensory radial nerves is variable, the axons destined for the extensor carpi radialis brevis can originate from the radial nerve proper, or from one of these two distal branches. The brachialis muscle receives some innervation from the radial nerve in this region (in addition to its main innervation from the musculocutaneous nerve). However, this innervation to the brachialis is usually not enough to flex the arm in the presence of musculocutaneous nerve palsy.

Figure 3-10 Supinator (C6, C7) assessment: The supinator should be tested with the forearm extended, to minimize substitution by the biceps brachii. The patient maintains the forearm in supination as you attempt to pronate it.

The Posterior Interosseous Nerve

The Superficial Group

After passing through the supinator and entering the extensor compartment, the posterior interosseous nerve supplies the superficial group of extensor muscles. This group is made up of the extensor carpi ulnaris, the extensor digitorum communis, and the extensor digiti minimi, which are often supplied by a common branch. Test the extensor carpi ulnaris (C7, C8) by stabilizing the distal forearm and having the patient extend and adduct (bend in the ulnar direction) the hand (Fig. 3-11). This muscle’s tendon at the wrist can be seen and felt. The extensor digitorum communis (C7, C8) extends the second to fifth digits at the metacarpal-phalangeal (knuckle) joints. To evaluate this muscle, each finger is extended at the knuckle joint with the forearm and hand well supported in a neutral position. The second (index finger) and fifth digits (small finger) have supplementary extensors, the extensor indicis and digiti minimi, respectively, while the third and fourth do not. Apply resistance just proximal to the proximal interphalangeal joint. The distal finger joints are allowed to relax in flexion (Fig. 3-12). Another way to test finger extension at the knuckle joint is to have the patient put his or her hand and wrist on a flat surface and ask them to extend the fingers either together or individually. The patient should not be allowed to simultaneously flex at the wrist because in doing so, the fingers will extend secondary to tenodesis (i.e., passive movement of a distal joint by changing the distance that a tendon travels by flexing or extending a more proximal joint). The extensor digiti minimi (C7, C8) acts in similar fashion as the extensor digitorum communis, yet only upon the fifth digit (Fig. 3-13). Keep in mind this digit is normally quite weak and should be compared with the normal hand.

Figure 3-11 Extensor carpi ulnaris (C7, C8) assessment: Test by stabilizing the distal forearm and having the patient extend and adduct (bend in an ulnar direction) the hand. This muscle’s tendon at the wrist’s edge can be seen and felt.

Figure 3-12 Extensor digitorum communis (C7, C8) assessment: To evaluate this muscle, each finger is extended at the knuckle joint with the forearm and hand well supported in a neutral position. Resistance is applied just proximal to the proximal interphalangeal joint. The distal finger joints are allowed to relax in flexion.

The Deep Group

The deep extensor compartment group may be innervated by separate branches (more common), or it may be innervated via a common (“descending”) branch from the posterior interosseous nerve, and include muscles that act upon the thumb and forefinger: the abductor pollicis longus, the extensor pollicis longus, the extensor pollicis brevis, and the extensor indicis. These are the most distally innervated radial muscles, and therefore are the last to be reinnervated following radial nerve injury. The abductor pollicis longus (C7, C8) acts to abduct the thumb in a radial direction (in the plane of the palm), unlike the median innervated abductor pollicis brevis, which primarily controls palmar abduction of the thumb. Therefore, one should test the abductor pollicis longus by stabilizing the hand and having the patient move an already extended thumb away from the index finger in the plane of the palm (Fig. 3-14). Alternatively, thumb extension can be assessed with the hand as a fist, resting on its ulnar surface. The thumb is extended away from the other fingers, as if the patient was hitchhiking. The extensor pollicis longus (C7, C8) extends the interphalangeal joint (Fig. 3-15); the extensor pollicis brevis (C7, C8) extends at the metacarpal-phalangeal joint (Fig. 3-16). This can be remembered by thinking of the extensor pollicis longus versus the extensor pollicis brevis: the “longer” of the two crosses the more distal joint. The tendons of these three thumb muscles can be seen and palpated around the “snuff box” or scaphoid bone. The sole extensor pollicis longus tendon is the distal border, whereas the abductor pollicis longus (more medial) and extensor pollicis brevis (more lateral), together form the proximal tendinous border. The extensor indicis (C7, C8) acts only upon the index finger, and is examined like the extensor digitorum communis (Fig. 3-12).

Figure 3-13 Extensor digiti minimi (C7, C8) assessment: This muscle acts in similar fashion as the extensor digitorum communis, yet only upon the fifth digit. The fifth digit is extended at the metacarpal-phalangeal joint while its distal interphalangeal joints are relaxed in flexion.

Figure 3-14 Abductor pollicis longus (C7, C8) assessment: This muscle abducts the thumb in a radial direction (in the plane of the palm), unlike the median innervated abductor pollicis brevis, which controls palmar abduction of the thumb. Therefore, one should test the abductor pollicis longus by stabilizing the hand and having the patient move an extended thumb away from the index finger in the plane of the palm.

Figure 3-15 Extensor pollicis longus (C7, C8) assessment: Thumb extension is best assessed with the hand as a fist, resting on its ulnar surface. The thumb is extended away from the other fingers, as if the patient is hitchhiking. Resistance is applied to the distal phalange to assess the extensor pollicis longus muscle.

Figure 3-16 Extensor pollicis brevis (C7, C8) assessment: Thumb extension is best assessed with the hand as a fist, resting on its ulnar surface. The thumb is extended away from the other fingers, as if the patient is hitchhiking. Resistance is applied to the proximal phalange to assess the extensor pollicis brevis muscle.

The posterior interosseous nerve usually ends at the wrist by innervating the dorsal carpal bone joints. Rarely, this nerve can communicate with the deep motor branch of the ulnar nerve, and control the first (and perhaps the first through third) dorsal interossei muscles. This anomalous extension is called the Froment-Rauber nerve.

The posterior interosseous nerve usually ends at the wrist by innervating the dorsal carpal bone joints. Rarely, this nerve can communicate with the deep motor branch of the ulnar nerve, and control the first (and perhaps the first through third) dorsal interossei muscles. This anomalous extension is called the Froment-Rauber nerve.

Sensory Innervation

Sensory Innervation

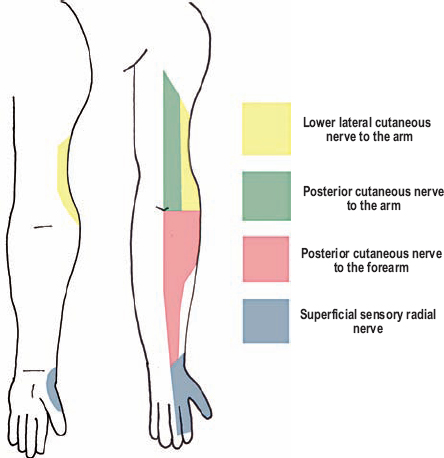

Deficits involving the radial nerve’s sensory branches can help localize the level of injury. These sensory territories are depicted in Fig. 3-17.

The Posterior Cutaneous Nerve to the Arm

The posterior cutaneous nerve to the arm is the first sensory branch from the radial nerve. It originates in the axilla, passes distally with the radial nerve between the long and medial heads of the triceps, and then pierces the lateral triceps head, or, alternatively, the fascia between the lateral and long triceps heads, to become subcutaneous. This nerve runs subcutaneously down the posterior aspect of the arm to the olecranon, a course that reflects its sensory territory. Therefore, sensory loss in the posterior arm is usually indicative of a radial nerve lesion proximal to the spiral groove.

Figure 3-17 Radial nerve sensory branches. The radial nerve carries sensation from the posterior arm, lower lateral arm, posterior forearm, and dorsomedial surface of the hand. Deficits involving these sensory branches can help localize the level of radial nerve injury.

The Lower Lateral Cutaneous Nerve to the Arm

The lower lateral cutaneous nerve to the arm originates from the radial nerve in the spiral groove, and subsequently pierces the brachial fascia at the lateral intermuscular septum to become subcutaneous. This branch’s sensory territory includes the lower lateral arm below the deltoid. Sensory loss in this territory, with preserved posterior arm sensation, points toward a radial nerve injury in the spiral groove.

The Posterior Cutaneous Nerve to the Forearm

The posterior cutaneous nerve to the forearm branches from the radial nerve in the brachial-axillary angle, proximal to the origin of the lower lateral cutaneous nerve to the arm. The posterior cutaneous nerve to the forearm runs with the radial nerve in the spiral groove, and then pierces the brachial fascia with the lower lateral cutaneous nerve to the arm at the lateral intermuscular septum. Once subcutaneous, the posterior cutaneous nerve to the forearm passes posterior to the lateral epicondyle, and lateral to the olecranon. Its sensory territory includes the dorsolateral aspect of the forearm.

The Superficial Sensory Radial Nerve

As mentioned previously, the superficial sensory radial nerve runs down the forearm in a cleft between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus muscles. After becoming subcutaneous and entering the dorsum of the wrist, this nerve provides sensation to the dorsolateral half of the hand, as well as the proximal two thirds of the second, third, and lateral half of the fourth digits. The more lateral portion of the thumb is also part of this nerve’s sensory territory. Opinions differ as to where the most “autonomous” zone for this nerve is located. Some include the anatomical snuff box (between the extensor pollicis longus and brevis tendons), the first dorsal web space, and the area over the distal one half of the second metacarpal bone.

There is much variation in sensory territories between the superficial sensory radial nerve and both the dorsal ulnar cutaneous and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerves. Because of this overlap, isolated lesions to the superficial sensory radial nerve may only yield a small area of sensory loss, which disappears over time. For this reason, the superficial sensory radial nerve is called the sural nerve of the arm, and is often harvested for graft repairs or biopsies.

There is much variation in sensory territories between the superficial sensory radial nerve and both the dorsal ulnar cutaneous and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerves. Because of this overlap, isolated lesions to the superficial sensory radial nerve may only yield a small area of sensory loss, which disappears over time. For this reason, the superficial sensory radial nerve is called the sural nerve of the arm, and is often harvested for graft repairs or biopsies.

Clinical Findings and Syndromes

Clinical Findings and Syndromes

Radial nerve deficits can be profound. Paralysis of wrist and finger extensors is debilitating because without this movement the hand cannot be placed in a functionally useful position. Furthermore, radial sensory deficits to the dorsal hand, although not important for fine finger function, may be misdiagnosed and progress to refractory neuropathic pain syndromes. Triceps palsies are rare because branches to these muscles originate high in the axilla. Even when present, triceps palsies are not too disabling because gravity helps substitute for its action. Following radial nerve injury (traumatic, idiopathic, or iatrogenic), reinnervation is frequently more robust than that seen following either median or ulnar injury, likely because the radial nerve does not innervate any hand intrinsic muscles. Nevertheless, radial nerve controlled finger and thumb extension often does not return. Because these movements are required for proper hand intrinsic function, their permanent paralysis becomes a common indication for tendon transfers.

The Arm

Complete Palsy in the Axilla

Proximal radial nerve palsies are secondary to trauma, pressure palsies, or occasionally from a posteriorly misplaced deltoid injection. Pressure palsies include crutch, Saturday night, and honeymooner’s. A high radial palsy (rare) in the axilla can cause both triceps weakness and posterior arm sensory loss, two deficits that distinguish it from more common radial nerve injuries at the spiral groove. Injuries affecting the radial nerve may be differentiated from posterior cord involvement by confirming normal deltoid (axillary off posterior cord) and latissimus dorsi (thoracodorsal off posterior cord) strength. Furthermore, patients with C7 palsies can be distinguished because they usually have numbness in both the volar and dorsal aspects of the third digit (middle finger), with sensory loss not extending proximal to the wrist. Additionally, C7 muscles innervated by the median nerve, including the pronator teres and flexor carpi radialis longus, should also be weak.

A complete radial palsy presents with sensory loss along the posterior arm and forearm, the lower anterolateral arm, as well as the dorsolateral hand. All extensors of the arm are weak. The triceps are weak and the triceps reflex is absent. Forearm flexion may be somewhat weak compared with the normal side, secondary to brachioradialis paralysis. There is a wrist drop from extensor carpi radialis (longus and brevis) and extensor carpi ulnaris weakness. The fingers cannot extend at the knuckle joint. Supination is partially weak, with residual supination performed by the biceps brachii. The wrist and hand appear limp, with the fingers semiflexed and the metacarpal bone of the thumb volar to the palm (Fig. 3-18). Distal finger extension is possible secondary to lumbrical function.

Be aware of certain movements that may mimic true proximal finger extension. When the wrist is flexed, tenodesis causes the fingers to extend. This phenomenon may be exaggerated when sclerosis is present from chronic extensor paralysis. Furthermore, with the fingers partially flexed, the hand intrinsics may partially extend the knuckle joints. To remove these effects, examine metacarpal joint extension with the wrist held in extension or on a flat surface.

Be aware of certain movements that may mimic true proximal finger extension. When the wrist is flexed, tenodesis causes the fingers to extend. This phenomenon may be exaggerated when sclerosis is present from chronic extensor paralysis. Furthermore, with the fingers partially flexed, the hand intrinsics may partially extend the knuckle joints. To remove these effects, examine metacarpal joint extension with the wrist held in extension or on a flat surface.

Figure 3-18 Wrist and finger drop secondary to a radial nerve palsy. The wrist and hand appear limp with the fingers semiflexed and the first metacarpal bone (of the thumb) volarto the palm.

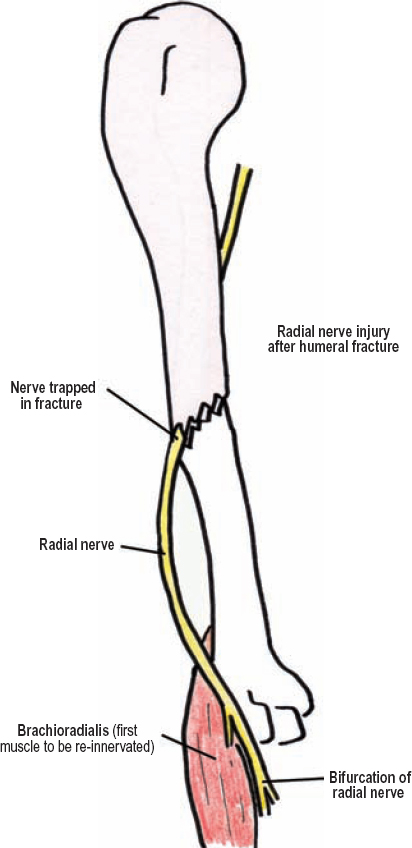

Radial Nerve Damage in the Spiral Groove

The spiral groove is the most common location for traumatic radial nerve palsy. The radial nerve can be directly contused against the humerus, or damaged by a fracture of the midhumeral shaft. It is estimated that approximately 15% of mid-humeral fractures affect the radial nerve. With a humeral fracture, the radial nerve remains tethered where it pierces the lateral intermuscular septum, and because of this immobility, can be transposed between the fractured bone ends (Fig. 3-19). A distally misplaced deltoid injection may also damage the radial nerve in this region.

Figure 3-19 Radial nerve injury following humeral fracture. With a humeral fracture, the radial nerve remains tethered where it pierces the lateral intermuscular septum; because of this immobility, it can become pinned between the two ends of fractured bone.

Radial nerve lesions at the spiral groove cause weakness of all muscles distal to the elbow, including the brachioradialis. The triceps are usually spared, as is the triceps reflex. Loss of sensation along the lower lateral arm and posterior forearm usually occurs, whereas the posterior cutaneous nerve to the arm is spared because it does not run in the spiral groove. The brachioradialis is the most proximal muscle to be reinnervated following radial nerve injury at the spiral groove, a process that usually takes 3 to 4 months.

In some patients, damage to the radial nerve at the spiral groove may cause mild triceps weakness. This is because supplementary, direct muscular branches to the lateral and medial heads from the radial nerve originate in the spiral groove, where they may be injured.

In some patients, damage to the radial nerve at the spiral groove may cause mild triceps weakness. This is because supplementary, direct muscular branches to the lateral and medial heads from the radial nerve originate in the spiral groove, where they may be injured.

The Antecubital Fossa

Radial Tunnel Syndrome

The existence of radial tunnel syndrome remains controversial. This is because, by definition, this syndrome has no objective motor or sensory deficits on examination or electrodiagnostic studies. If these are present, especially finger extension weakness, one must also consider other diagnoses, specifically posterior interosseous nerve compression at the supinator. Anatomically, radial tunnel syndrome is defined as the submuscular path where the radial nerve travels between the lateral intermuscular septum and the supinator. Between these two points, the brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, and extensor carpi radialis brevis muscles sequentially cover the radial nerve. The extensor carpi radialis brevis actually envelops the nerve, by passing both deep and superficial to it. Some experts propose that irritation of the radial nerve in the radial tunnel can be secondary to an anomalous tendinous ridge on the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle. Other compression points may include fibrous bands, or irregularities, on the anterior margin of the elbow joint or radial head, or alternatively, a fan of small arterial branches from the recurrent radial artery.

Radial tunnel syndrome and tennis elbow (i.e., lateral epicondylitis) have very similar presentations. Diagnostic criteria for radial tunnel syndrome include (1) being unresponsive to conservative treatment of tennis elbow, (2) pain at the radial tunnel (not the lateral epicondyle) during resisted third digit extension when the elbow is fully extended and the forearm supinated, and (3) nerve tenderness at rest in the radial tunnel. The third digit is believed to instigate the most pain because the extensor carpi radialis brevis inserts on the third metacarpal bone (the extensor carpi radialis longus inserts on the second). Forced supination may also cause pain if the radial tunnel is simultaneously palpated.

In contrast, tennis elbow is secondary to forced, repetitive pronation and wrist extension causing inflammation where the extensor muscles attach to the lateral epicondyle. Relief of symptoms with a cortisone injection at the lateral epicondyle is often diagnostic of tennis elbow. Patients with tennis elbow have pain at the lateral epicondyle, not the radial tunnel, and classically have worsened pain when the hand is passively pronated and flexed (putting the effected tendinous insertions on stretch). The pain of tennis elbow is often sharp and localized, whereas that for radial tunnel syndrome is more a dull ache, deep in the muscles.

In contrast, tennis elbow is secondary to forced, repetitive pronation and wrist extension causing inflammation where the extensor muscles attach to the lateral epicondyle. Relief of symptoms with a cortisone injection at the lateral epicondyle is often diagnostic of tennis elbow. Patients with tennis elbow have pain at the lateral epicondyle, not the radial tunnel, and classically have worsened pain when the hand is passively pronated and flexed (putting the effected tendinous insertions on stretch). The pain of tennis elbow is often sharp and localized, whereas that for radial tunnel syndrome is more a dull ache, deep in the muscles.

Supinator Syndrome

Supinator syndrome is usually a spontaneous palsy of the posterior interosseous nerve secondary to compression or irritation where this nerve enters the supinator muscle. The posterior interosseous nerve passes between the superficial and deep heads of this muscle, analogous to placing your index finger into the front pocket of a pair of jeans. The anterior margin of this “pocket” is termed the arcade of Frohse, and in 30% of the population is very fibrous and thought to predispose to nerve compression (Fig. 3-20). Some patients with this syndrome have a history of mild trauma to this region, or alternatively, report repetitive supination movements at work or play.

Patients with supinator syndrome often have pain localized to the supinator muscle, which worsens after a few minutes of forced supination. By history, they have either sudden or progressive finger extension weakness. The supinator muscle itself is classically spared in supinator syndrome because most branches to this muscle occur prior to the nerve entering the muscle. Sensation is normal in the territory of the superficial sensory radial nerve, and the brachioradialis muscle has normal strength. Like radial tunnel syndrome, the existence of supinator syndrome is also somewhat controversial. Some experts believe that many patients diagnosed with this syndrome actually have focal cases of inflammatory neuritis (i.e., Parsonage–Turner syndrome). Therefore, subtle palsies of other upper extremity nerves, as well as any contralateral upper extremity weakness, should be ruled out.

The healing of a proximal forearm or elbow fracture in misalignment, or with excessive pannus (including from osteomyelitis), may put the posterior interosseous nerve, which is fixed at its entrance into the supinator muscle, under tension. The resultant palsy, termed tardive radial palsy, usually occurs months to years later. This classically occurs after a Monteggia fracture: a proximal ulnar fracture with concurrent posterior dislocation of the radius. Radiographs are diagnostic.

The healing of a proximal forearm or elbow fracture in misalignment, or with excessive pannus (including from osteomyelitis), may put the posterior interosseous nerve, which is fixed at its entrance into the supinator muscle, under tension. The resultant palsy, termed tardive radial palsy, usually occurs months to years later. This classically occurs after a Monteggia fracture: a proximal ulnar fracture with concurrent posterior dislocation of the radius. Radiographs are diagnostic.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis are predisposed to finger extension weakness. They can have synovial thickening at the elbow that compresses the radial nerve directly or indirectly by elevating the supinator, which places the posterior interosseous nerve on stretch. Rheumatoid arthritis patients can also rupture extensor tendons, which can mimic nerve palsy.

Figure 3-20 Supinator syndrome. The posterior interosseous nerve may be irritated where it enters the supinator muscle. It passes between the superficial and deep heads of this muscle, analogous to placing your index finger into the front pocket of a pair of jeans. The anterior margin of this “pocket” is termed the arcade of Frohse, which may be very fibrous and cause nerve compression.

The Forearm

Posterior Interosseous Nerve Palsy

Posterior interosseous nerve palsy can be from trauma, diabetic mononeuropathy, compression at the supinator muscle (supinator syndrome), or from a space-occupying mass, or it can be idiopathic (i.e., Parsonage–Turner syndrome). The most common soft tissue mass compressing the posterior interosseus nerve is a lipoma, followed by nerve sheath tumors, ganglia, and hypertrophic synovium (rheumatoid arthritis). Considering it carries no cutaneous sensory fibers, sensation remains normal when this palsy occurs. However, patients may complain of a dull ache in the proximal forearm extensor muscles, near the radial head.

The motor weakness that occurs in a posterior interosseous palsy has two components: wrist extension weakness in an ulnar direction (radial wrist extension remains normal, mediated by the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis), and finger extension weakness at the metacarpal-phalangeal joints. Of note, patients do not have a wrist drop because the extensor carpi radialis muscles are unaffected. Upon wrist extension, however, the hand deviates in a radial direction because the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle is weak. Isolated posterior interosseous nerve palsy is further confirmed by documenting normal brachioradialis and superficial sensory radial nerve function. Patients with partial posterior interosseous nerve lesions can have variable and progressive weakness in each finger. When weakness begins in only the fourth and fifth digits, a pseudo-ulnar claw hand can be seen. By observation alone, this sign can be easily distinguished because there is no hyper-extension at the knuckle joints, as is required for true claw hand.

Supinator and extensor carpi radialis brevis weakness may also occur in a posterior interosseous nerve palsy, depending on each person’s specific branching anatomy. Nevertheless, confirming normal brachioradialis and superficial radial sensory nerve function is paramount for making this diagnosis.

Supinator and extensor carpi radialis brevis weakness may also occur in a posterior interosseous nerve palsy, depending on each person’s specific branching anatomy. Nevertheless, confirming normal brachioradialis and superficial radial sensory nerve function is paramount for making this diagnosis.

Sensory Radial Nerve Palsy (Wartenberg Syndrome)

Isolated damage to the superficial sensory radial nerve can occur from trauma, tight handcuffs or watches, venipuncture, surgery for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, and occasionally from scissor-like pinching between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus tendons. Wartenberg syndrome or cheiralgia paresthetica are synonymous with superficial sensory radial nerve palsy. Injury to this sensory nerve causes numbness, hyperesthesia, and burning pain on the dorsolateral aspect of the hand. With misdiagnosis and lack of treatment, this pain may become permanent and neuropathic, and therefore difficult to treat. The superficial sensory radial nerve pierces the antebrachial fascia approximately two thirds down the forearm at the lateral radial border, right between the tendons of the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus (Fig. 3-21). With repetitive pronation, the brachioradialis tendon normally closes the space between these two tendons in a scissor-like fashion, potentially irritating the nerve where it emerges from the fascia. In these patients, pain and numbness can be exacerbated with simultaneous forced pronation and ulnar wrist deviation, which scissors the tendons together and stretches the nerve, respectively. A Tinel’s sign can often be elicited. This diagnosis may be confirmed with electrodiagnostic testing.

Figure 3-21 Superficial sensory radial nerve entrapment in the distal forearm. With repetitive pronation, the brachioradialis tendon normally closes the space between these two tendons in a scissor-like fashion, potentially irritating the nerve where it emerges from the fascia.

De Quervain’s tenosynovitis, or stenosing tenosynovitis of the first thumb’s extensor tendon, may be confused with superficial sensory radial nerve palsy. The Finkelstein sign for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis occurs if passively bending the hand (as a fist) in an ulnar direction causes pain in the lateral wrist area. A superficial sensory radial nerve palsy may also have a positive Finkelstein sign. These two problems are clinically differentiated by the fact that the nerve palsy more frequently causes sensory loss.

De Quervain’s tenosynovitis, or stenosing tenosynovitis of the first thumb’s extensor tendon, may be confused with superficial sensory radial nerve palsy. The Finkelstein sign for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis occurs if passively bending the hand (as a fist) in an ulnar direction causes pain in the lateral wrist area. A superficial sensory radial nerve palsy may also have a positive Finkelstein sign. These two problems are clinically differentiated by the fact that the nerve palsy more frequently causes sensory loss.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree