2

The Diagnostic Anatomy of the Ulnar Nerve

The ulnar nerve innervates most of the hand intrinsic muscles, and therefore is the nerve that is predominantly responsible for controlling fine, coordinated hand movements. Otherwise, the ulnar nerve innervates no muscles in the upper arm, and only two in the forearm. It does not travel in the midline like the median nerve, but instead takes a direct, yet hidden, route from the axilla down to the hypothenar eminence. From proximal to distal, the ulnar nerve hides in the medial head of the triceps, passes along the backside of the elbow, runs down the forearm under the flexor carpi ulnaris, and enters finally into Guyon’s tunnel at the wrist. Commensurate with its surreptitious approach to the deep palmar area, a severe ulnar deficit can manifest itself as a claw hand. The most common location of ulnar nerve entrapment is not at the wrist, like for the median nerve, but instead behind the elbow, where the ulnar nerve is superficial and vulnerable to dynamic compression.

Anatomical Course

Anatomical Course

The Arm

The brachial plexus cords are named based on their relationship to the axillary artery under the pectoralis minor, and because the ulnar nerve is a continuation of the medial cord, it naturally begins (and remains) medial to the axillary artery. After its contribution to the median nerve, the medial cord continues distally as the ulnar nerve. The ulnar nerve comprises predominantly fibers from the C8 and T1 spinal nerves. However, C7 input may also be present (see below).

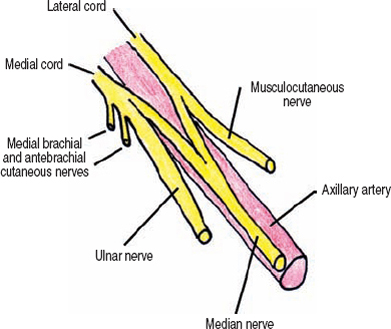

The transformation of the medial and lateral cords into their terminal branches is M-shaped, and lies over the anterior aspect of the axillary artery. The lateral leg of the letter M is the musculocutaneous nerve; the medial leg is the ulnar nerve. The center, V-shaped, convergence consists of components of the lateral and medial cords merging to become the median nerve (Fig. 2-1).

Before the medial cord becomes the ulnar nerve, it yields two important sensory branches, the medial brachial cutaneous and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves, which innervate the medial half of the arm and forearm, respectively (Fig. 2-2). Despite being branches from the medial cord, for simplicity’s sake, these nerves will be considered part of the ulnar nerve’s sensory territory. If one considers these two nerves as “very proximal” branches of the ulnar nerve, then one can simply say that the ulnar nerve’s sensory territory is the medial half of the whole upper limb, including the hand.

Figure 2-1 Origin of the ulnar nerve in the axilla. The transformation of the medial and lateral cords into their terminal branches is M-shaped, and lies over the anterior aspect of the axillary artery. The lateral leg of the letter M isthemusculocutaneous nerve; the medial leg is the ulnar nerve. The center, V-shaped convergence consists of contributions from the lateral and medial cords merging to become the median nerve.

The medial brachial cutaneous nerve pierces the superficial fascia of the arm near the axilla and then runs in the subcutaneous space innervating the medial surface of the arm. The distal portion of this nerve may reach an area posterior to the medial epicondyle, and in this region be inadvertently transected during ulnar nerve decompressions.

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve branches into an anterior and posterior branch just proximal, and anterior, to the medial epicondyle. Near this area of bifurcation, components of this nerve pierce the superficial fascia of the arm and enter the subcutaneous space. The anterior division runs along the anteromedial forearm, while the posterior branch runs along the posteromedial aspect of the forearm. The posterior branch often crosses the field of operative exposure for decompression of the ulnar nerve, while the anterior branch can be harmed when the median nerve is exposed in the antecubital fossa.

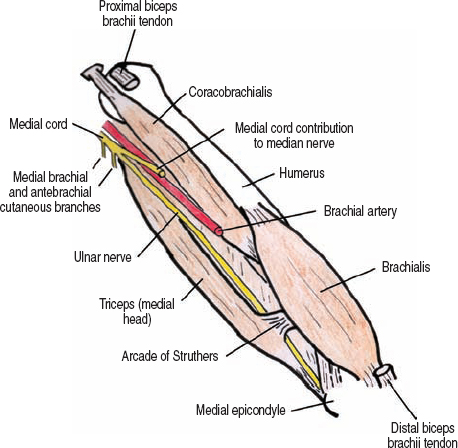

Down the upper half of the arm, the ulnar nerve runs along the brachial artery’s medial aspect, opposite the median nerve, which runs on the brachial artery’s lateral side (Fig. 2-3). Proximally, the ulnar nerve lies on the anterior border of the intermuscular septum, a thick fascial plane that separates the flexor and extensor compartments of the arm. At about the coracobrachialis muscle’s insertion into the humerus, which occurs halfway down the arm, the ulnar nerve pierces this intermuscular septum. The superior ulnar collateral artery, a branch from the brachial artery, runs with the ulnar nerve through this septum. Once piercing the intermuscular septum, the ulnar nerve becomes enveloped within the anteromedial aspect of the medial head of the triceps, inside of which it continues down the arm. In approximately 50% of persons, an extension of the intermuscular septum forms an arch, or arcade, that attaches to the medial head of the triceps. This structure is a few centimeters in length and is termed the arcade of Struthers, and is located about two thirds of the way down the arm. The ulnar nerve, which is deep and enveloped in the medial triceps head, runs under this arcade, when present. The arcade of Struthers should not be confused with the ligament of Struthers, which bridges an anomalous supracondylar ridge on the distal humeral shaft to the medial humeral epicondyle (see median nerve chapter). As the medial head of the triceps narrows into its distal tendon, the ulnar nerve emerges from its passage within this muscle and enters the posteromedial elbow region. The inferior ulnar artery, which also arises from the brachial artery, joins the ulnar nerve at this level. Branches of the inferior ulnar artery adhere to, and pass with, the ulnar nerve through the elbow region.

Figure 2-2 Course of the medial brachial and antebrachial cutaneous nerves. Before the medial cord becomes the ulnar nerve, it yields two important sensory branches, the medial brachial cutaneous and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves, which innervate the medial half of the arm and forearm, respectively.

Figure 2-3 The course of the ulnar nerve in the arm. In the proximal arm, the ulnar nerve lies on the anterior border of the intermuscular septum. Once piercing the intermuscular septum, the ulnar nerve becomes enveloped within the anteromedial aspect of the medial head of the triceps, inside of which it continues down the arm.

The mobility of the ulnar nerve changes as it passes down the medial arm. When anterior to the intermuscular septum in the upper half of the arm the ulnar nerve is mobile. However, it subsequently becomes immobilized in the lower half of the arm by being imbedded in the triceps muscle, and under the arcade of Struthers, when present. The ulnar nerve becomes once again mobile just proximal to the postcondylar groove of the elbow.

In many individuals, there is a C7 contribution to the ulnar nerve, which originates from the lateral cord. This neural communication within the brachial plexus has been labeled the lateral root of the ulnar nerve. In a minority of people the antebrachial cutaneous nerve, or even the more proximal medial brachial cutaneous nerve, can originate directly from the ulnar nerve, providing another reason for these sensory branches to be categorized with the ulnar nerve.

In many individuals, there is a C7 contribution to the ulnar nerve, which originates from the lateral cord. This neural communication within the brachial plexus has been labeled the lateral root of the ulnar nerve. In a minority of people the antebrachial cutaneous nerve, or even the more proximal medial brachial cutaneous nerve, can originate directly from the ulnar nerve, providing another reason for these sensory branches to be categorized with the ulnar nerve.

The Elbow

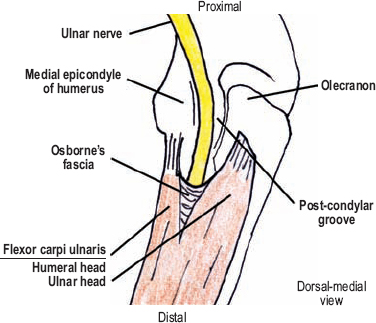

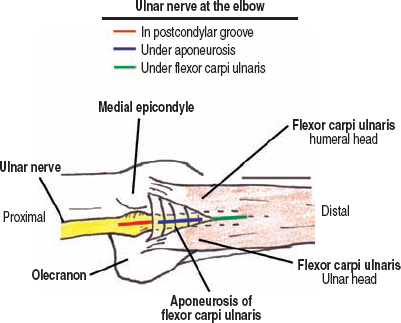

After emerging from the medial head of the triceps in the lower arm, the ulnar nerve runs subcutaneously and enters the postcondylar groove. This groove is a curvilinear bony canal between the medial epicondyle of the humerus (lying anterior and medial), and the olecranon of the ulna (posterior and lateral). It is within this grove that the ulnar nerve is most vulnerable to external trauma. After passing distal to the elbow, the ulnar nerve once again dives below a protective muscle, this time between the humeral and ulnar heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris.

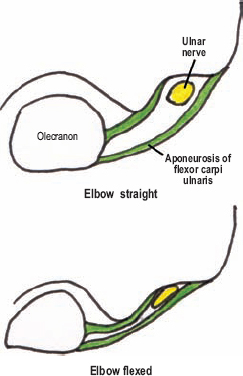

This region, just beyond the bony postcondylar groove, is the cubital tunnel. It has two segments (Fig. 2-4): The first is where the nerve passes under the aponeurosis that connects the two proximal tendons of the flexor carpi ulnaris. Although variable, this aponeurosis can extend proximally, connecting the medial epicondyle to the olecranon. Therefore, it may in fact cover the bony postcondylar groove. The second segment is where the ulnar nerve passes between, and deep to, the two muscular heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris. The aponeurosis between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris is very thick in approximately 75% of the population, and is then called Osborne’s band. As will be discussed below, Osborne’s band has been implicated in ulnar nerve compression.

Dynamic anatomy at the elbow is important. As the elbow flexes, the aponeurosis of the flexor carpi ulnaris is under tension, potentially compressing the ulnar nerve underneath (Fig. 2-5). Furthermore, with contraction of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle itself, the ulnar nerve may be further compressed under the second, more distal, portion of the cubital tunnel. This is partly why simultaneous elbow flexion and wrist flexion in an ulnar direction can precipitate symptoms of ulnar entrapment at the elbow.

The amount of aponeurosis covering the postcondylar groove, as well as the space between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris, is variable. In fact, some patients may not have this covering at all, allowing the ulnar nerve to slip, or “snap” over the medial epicondyle during forearm flexion. The anconeus epitrochlearis muscle is present in approximately 10% of the population. This muscle spans from the medial epicondyle to the olecranon, and is a potential cause of ulnar nerve irritation.

The amount of aponeurosis covering the postcondylar groove, as well as the space between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris, is variable. In fact, some patients may not have this covering at all, allowing the ulnar nerve to slip, or “snap” over the medial epicondyle during forearm flexion. The anconeus epitrochlearis muscle is present in approximately 10% of the population. This muscle spans from the medial epicondyle to the olecranon, and is a potential cause of ulnar nerve irritation.

Figure 2-4 The elbow region and the cubital tunnel. After exiting the postcondylar groove, the ulnar nerve travels through the cubital tunnel. In approximately 75% of the population, the superficial aponeurosis between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris is very thick, and is called Osborne’s band or fascia.

Figure 2-5 As the forearm flexes at the elbow, the area of the cubital tunnel decreases. Furthermore, with contraction of the flexor carpi ulnaris, the submuscular portion of the cubital tunnel also constricts (not shown). This is why simultaneous forearm flexion and wrist flexion in an ulnar direction can precipitate symptoms of ulnar entrapment at the elbow.

The Forearm

After passing deep to the two proximal heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris, the ulnar nerve continues down the forearm between this muscle superficially and the flexor digitorum profundus below. The ulnar nerve usually provides only one major branch to the flexor digitorum profundus, which arises after the branches destined for the flexor carpi ulnaris have already exited. The ulnar nerve passes in a direct trajectory from the medial epicondyle to the pisiform bone in the wrist. In the distal third of the forearm, the ulnar nerve emerges from between the flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus, where these two muscles become tendinous. At this point, the ulnar nerve is not covered by muscle and lies between the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon medially, and the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon laterally. The ulnar artery, a branch from the brachial artery in the antecubital fossa, gradually makes its way medially to pair up with the ulnar nerve proximal to the wrist. Once together, these two structures enter the hand, with the artery lateral to the nerve.

Two sensory branches originate from the ulnar nerve in the distal half of the forearm. The first is the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve, which arises approximately 5 to 10 cm proximal to the wrist crease off the dorsomedial aspect of the ulnar nerve. This branch travels to the dorsum of the distal forearm between the ulna and the tendon of the flexor carpi ulnaris. Once on the dorsal surface, it pierces the antebrachial fascia and becomes subcutaneous a few centimeters proximal to the wrist. The second sensory branch from the ulnar nerve is the palmar ulnar cutaneous nerve, which is a mirror image of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. The palmar ulnar cutaneous nerve branches from the ulnar nerve approximately 5 to 10 cm proximal to the wrist from its volar-lateral surface and runs adherent to the ulnar nerve for a few centimeters. This branch enters the subcutaneous space proximal to the distal wrist crease and arborizes over the hypothenar eminence.

Although the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve usually originates proximal to the palmar ulnar cutaneous nerve, in certain people the reverse may be true. Alternatively, the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve may actually branch from the superficial sensory radial nerve. Communication, or “cross talk,” between the ulnar nerve and the anterior interosseous nerve via the Martin–Gruber anastomosis may occur in the forearm.

Although the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve usually originates proximal to the palmar ulnar cutaneous nerve, in certain people the reverse may be true. Alternatively, the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve may actually branch from the superficial sensory radial nerve. Communication, or “cross talk,” between the ulnar nerve and the anterior interosseous nerve via the Martin–Gruber anastomosis may occur in the forearm.

The Wrist/Hand

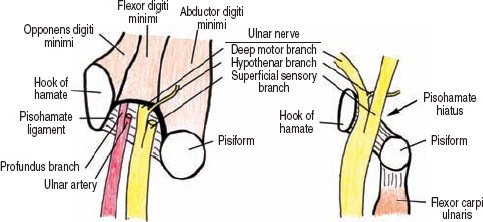

The ulnar nerve and artery enter the hand via Guyon’s tunnel (Fig. 2-6). Although Guyon’s tunnel has one proximal entrance, it has two distal exits, one going deeper into the hand, and the other remaining superficial. Upon entering this tunnel, the following structures are encountered. First, there is a large bump along the middle one half of the medial tunnel wall: the pisiform bone. Next at the distal third, there is another bump, but now on the lateral side: the hook of the hamate. At the end of the tunnel, there is a fork. The lateral pathway dives deep and almost immediately takes a sharp lateral bend. The medial pathway, however, continues in the same plane as the more proximal tunnel. In reviewing the boundaries of Guyon’s tunnel, one needs to consider its proximal and distal segments separately. Please note that in the following discussion, medial refers to the hypothenar margin of the hand and lateral refers to the thenar aspect of the hand.

In the proximal half of Guyon’s tunnel, the floor comprises the transverse carpal ligament and the roof the more superficial palmar carpal ligament (Fig. 2-7). The small palmaris brevis muscle also runs in the proximal roof of Guyon’s tunnel. By passing deeper on the lateral margin of Guyon’s tunnel, the superficial palmar carpal ligament briefly fuses with the transverse carpal ligament, thereby actually forming the lateral wall of Guyon’s tunnel. However, the superficial palmar carpal ligament is the lateral wall for only the proximal portion of the tunnel. The flexor carpi ulnaris tendon and the more distal pisiform bone (first bump in the wall described earlier) form the proximal, medial wall of the tunnel.

For the distal half of the tunnel, the lateral wall is formed by the hook of the hamate (second bump in the wall described previously), and the shorter medial wall by the pisiform bone. The distal floor is formed initially by the pisohamate ligament, then by the pisometacarpal ligament. The ulnar nerve passes superficial to both of these ligaments. The distal roof of Guyon’s tunnel continues to be formed by the palmar carpal ligament. However, a muscular arch of the hypothenar muscle mass, from the pisiform to the hook of the hamate, forms the roof of the deeper, distal branch tunnel. This muscular arch is mainly made up of the flexor digiti minimi. Entrance to this deeper branch tunnel has been termed the pisohamate hiatus.

Figure 2-6 The ulnar nerve at the wrist. The ulnar nerve and artery enter the hand via Guyon’s tunnel. Although Guyon’s tunnel has one proximal entrance, it has two distal exits, one going deeper into the hand, and the other remaining superficial.

Figure 2-7 Proximal cross section of Guyon’s tunnel. In the proximal half of Guyon’s tunnel, the floor comprises the transverse carpal ligament and the roof the more superficial palmar carpal ligament. By passing deeper on the lateral margin of Guyon’s tunnel, the superficial palmar carpal ligament fuses with the transverse carpal ligament, thereby also forming the lateral wall of Guyon’s tunnel.

The ulnar nerve bifurcates into a deep motor branch and a superficial sensory branch in the distal portion of Guyon’s tunnel. As their names imply, the superficial branch courses through the medial, more superficial tunnel with the main portion of the ulnar artery, while the deep branch goes down, with a profunda or deep branch of the ulnar artery, under the arch created by the flexor digiti minimi. This deep branch often pierces the opponens digiti muscle, but gives off a small side branch that innervates the hypothenar muscles just prior to it entering this deep passage. Once passing through Guyon’s tunnel into the hand, the deep motor branch curves lateral toward the midline of the hand and thenar eminence, remaining deep to the flexor tendons of the fingers. The superficial branch splits into digital nerves to the fourth and fifth digits.

Occasionally, there maybe early branching of the ulnar nerve with an anomalous course. For example, the ulnar nerve may branch proximal to the pisiform bone, with the superficial sensory branch communicating some, or all, of its sensory fibers to the palmar ulnar cutaneous nerve. A second variation occurs when the deep motor branch bifurcates prior to entering the pisohamate hiatus, with one branch entering the carpal tunnel lateral to the hook of the hamate, only to rejoin the deep branch in the palm.

Occasionally, there maybe early branching of the ulnar nerve with an anomalous course. For example, the ulnar nerve may branch proximal to the pisiform bone, with the superficial sensory branch communicating some, or all, of its sensory fibers to the palmar ulnar cutaneous nerve. A second variation occurs when the deep motor branch bifurcates prior to entering the pisohamate hiatus, with one branch entering the carpal tunnel lateral to the hook of the hamate, only to rejoin the deep branch in the palm.

Motor Innervation and Testing

Motor Innervation and Testing

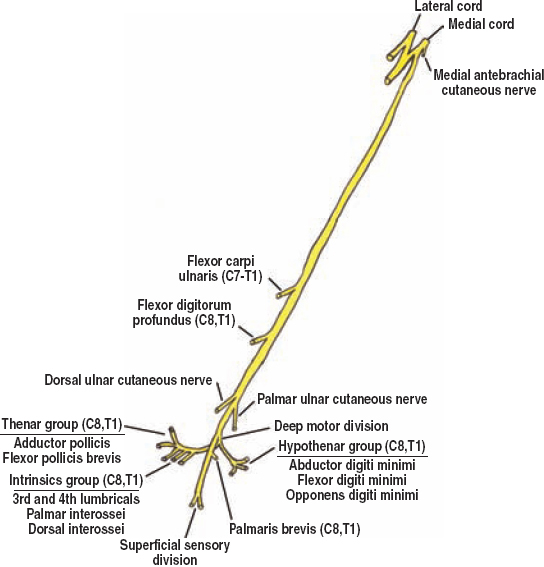

As mentioned earlier, the ulnar nerve innervates no muscles in the upper arm, but is predominantly responsible for fine, coordinated hand and finger movements (Fig. 2-8). The muscles innervated by the ulnar nerve may be grouped as follows: forearm (two muscles), hypothenar group (four muscles), hand intrinsic muscles or intrinsics (three groups of muscles), and the thenar group (two muscles).

The Forearm Group

The first muscle innervated by the ulnar nerve is the flexor carpi ulnaris (C7-T1). Branches to this muscle originate in the cubital tunnel, or just distal to it. Testing this muscle is a two-step process. First, while the patient abducts the ipsilateral fifth digit, observe and palpate the flexor carpi ulnaris’ tendon just proximal to the wrist (Fig. 2-9). The flexor carpi ulnaris contracts to stabilize the pisiform so that the abductor digiti minimi may function. Next, have the patient flex his or her wrist against resistance in an ulnar direction (Fig. 2-10), which is the primary action of this muscle.

The second muscle innervated by the ulnar nerve in the forearm is the flexor digitorum profundus (C8, T1) to the fourth and fifth digits. Branches to this muscle originate when the ulnar nerve is between the flexor digitorum profundus and the flexor carpi ulnaris in the proximal forearm. This muscle is tested in the same fashion as for its median innervated half, except one uses the fifth digit: Immobilize the proximal interphalangeal joint while the patient flexes the distal interphalangeal joint (Fig. 2-11).

In 5% of patients, branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris originate proximal to the elbow. Although the median nerve’s anterior interosseous branch may occasionally control distal interphalangeal joint flexion of the ring finger (in addition to the index and long fingers), the ulnar nerve always controls this movement in the fifth digit.

In 5% of patients, branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris originate proximal to the elbow. Although the median nerve’s anterior interosseous branch may occasionally control distal interphalangeal joint flexion of the ring finger (in addition to the index and long fingers), the ulnar nerve always controls this movement in the fifth digit.

Figure 2-8 Ulnar nerve motor innervation. The ulnar nerve innervates no muscles in the upper arm, but is predominantly responsible for fine, coordinated finger movements.

Figure 2-9 Flexor carpi ulnaris (C7-T1) assessment, stabilizing the pisiform: While the patient abducts the ipsilateral fifth digit, observe and palpate the flexor carpi ulnaris’ tendon just proximal to the wrist. The flexor carpi ulnaris contracts to stabilize the pisiform so that the abductor digiti minimi may function.

Figure 2-10 Flexor carpi ulnaris (C7-T1) assessment, wrist flexion: Have the patient flex his or her wrist against resistance in an ulnar direction, which is the primary action of this muscle.

The Hypothenar Group

As described, the ulnar nerve bifurcates into two divisions within Guyon’s tunnel: the superficial sensory and deep motor. The superficial sensory division innervates only one, often-forgotten muscle, the palmaris brevis (C8, T1). The small branch that innervates this muscle usually originates from the sensory division as it leaves the distal end of Guyon’s tunnel. The palmaris brevis is located in the roof of Guyon’s tunnel, and when contracted, corrugates the hypothenar skin. This deepens the hollow of the hand, possibly aiding in grasp. To test this muscle, have the patient forcibly abduct the fifth digit and ask them to “contract” the hypothenar eminence. Skin corrugation should occur (Fig. 2-12).

Figure 2-11 Flexor digitorum profundus (C8, T1) assessment: This muscle is tested in the same fashion as its median innervated half, except to evaluate the ulnar nerve contribution one uses the fifth digit. To test, immobilize the proximal interphalangeal joint while the patient flexes the distal interphalangeal joint against resistance.

Figure 2-12 Palmaris brevis (C8, T1) assessment: Test this muscle by having the patient forcibly abduct the fifth digit and then instructing them to “contract” the hypothenar eminence simultaneously. Skin corrugation should occur.

The deep motor division gives a small motor branch to the hypothenar eminence just before diving into the pisohamate hiatus. This branch innervates the three muscles of the hypothenar eminence: the abductor digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi, and the opponens digiti minimi. The abductor digiti minimi (C8, T1) is tested when the patient abducts the fifth digit against resistance (Fig. 2-13). One should keep in mind that this muscle is delicate, with even normal strength being easily overcome. The flexor digiti minimi (C8, T1) may be assessed by immobilizing the interphalangeal joints of the fifth digit, and instructing the patient to flex the metacarpal-phalangeal joint against resistance (Fig. 2-14). One cannot isolate this muscle’s function, however, because flexion of the fifth digit’s metacarpal-phalangeal joint is performed not only by the flexor digitiminimi, but also by the fourth lumbrical, and the interossei. Next, test the opponens digiti minimi (C8, T1) by having the patient hold the volar pads of the distal thumb and fifth digit together. While the patient maintains this position, try to force the distal fifth metacarpal away from the thumb (Fig. 2-15). Hypothenar wasting may be evident with chronic denervation of these muscles.

Figure 2-13 Abductor digiti minimi (C8, T1) assessment: This muscle is tested when the patient abducts the fifth digit against resistance. One should keep in mind that this muscle is delicate, the patient’s resistance is easily overcome even with normal strength.

Figure 2-14 Flexor digiti minimi (C8, T1) assessment: This muscle is tested by immobilizing the interphalangeal joints of the fifth digit and having the patient flex the metacarpal-phalangeal (knuckle) joint against resistance. One cannot isolate this muscle’s function, however, because flexion of the fifth digit’s metacarpal-phalangeal joint is performed by not only the flexor digiti minimi, but also by the fourth lumbrical and the interossei.

The Hand Intrinsic Muscles

The small and deeply situated hand intrinsic muscles can be placed into three groups: the lumbricals, the palmar interossei, and the dorsal interossei. The lumbricals help flex the metacarpal-phalangeal joints and extend the proximal interphalangeal joints when the metacarpal-phalangeal joints are immobilized in a hyperextended position. The dorsal interossei abduct or spread the fingers. The palmar interossei adduct or close the fingers; they also assist the lumbricals in flexing the metacarpal-phalangeal joints. The deep branch of the ulnar nerve innervates the third and fourth lumbricals (to the fourth and fifth digits), as well as all of the palmar and dorsal interossei muscles.

Figure 2-15 Opponensdigiti minimi (C8, T1) assessment: Have the patient hold the volar pads of the distal thumb and fifth digit together. While the patient maintains this position, try to force the proximal digit and distal fifth metacarpal away from the thumb.

To test the third and fourth lumbricals (C8, T1), immobilize the metacarpal-phalangeal joints of these two fingers in hyperextension and then test extension of the proximal interphalangeal joints against resistance (Fig. 2-16). A simple way to test the interossei is to concentrate on the index finger. On a flat surface have the patient both abduct (first dorsal interosseus [C8, T1 ], Fig. 2-17) or adduct (second palmar interosseous [C8, T1 ], Fig. 2-18) the index finger against resistance. Contraction or atrophy of the first dorsal interosseous muscle can be observed and palpated on the dorsum of the hand. Also secondary to dorsal interossei wasting, the extensor tendons on the dorsum of the hand may appear more prominent when compared with the normal hand. The palmar interossei may also be assessed by having the patient maintain extended fingers together as you attempt to pass a digit between them.

Figure 2-16 Third and fourth lumbrical (C8, T1) assessment: Immobilize the metacarpal-phalangeal joints of these two fingers in hyperextension and then test extension of the proximal interphalangeal joints against resistance.

Figure 2-17 First dorsal interosseous (C8, T1) assessment: On a flat surface, the patient abducts his or her index finger against resistance. Contraction or atrophy of the first dorsal interosseous muscle can be observed and palpated on the dorsum of the hand.

Figure 2-18 Second palmar interosseous (C8, T1) assessment: On a flat surface, the patient adducts the index finger against resistance. Alternatively, the patient can be instructed to keep the extended fingers together as the you attempt to pass a digit between them (not shown).

The long finger flexors (flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus) can substitute for digit adduction when the fingers are flexed. The finger extensors, in corollary, can help abduct the digits when the fingers are extended. To eliminate these substitutions and isolate the interossei, the fingers should be in extension at the metacarpal-phalangeal joints when assessed.

The long finger flexors (flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus) can substitute for digit adduction when the fingers are flexed. The finger extensors, in corollary, can help abduct the digits when the fingers are extended. To eliminate these substitutions and isolate the interossei, the fingers should be in extension at the metacarpal-phalangeal joints when assessed.

The Thenar Group

The ulnar nerve innervates two muscles of the median nerve-dominated thenar eminence. The first is the adductor pollicis (C8, T1). Test this muscle by having the patient adduct the straightened thumb in a plane parallel to the palm (Fig. 2-19). Try to separate the thumb from the lateral border of the palm. Alternatively, you may place your index finger between his or her thumb and lateral palm, applying resistance as the thumb is adducted. Because of its large size, atrophy of this muscle alone may cause thenar wasting. The second muscle is the deep head of the flexor pollicis brevis (C8, T1), with its superficial head being innervated by the median nerve. Although not a very useful muscle to test because of its dual innervation, some weakness compared with the other side may be seen with ulnar lesions. To test this muscle, the patient flexes the thumb’s metacarpal-phalangeal joint, while the interphalangeal joint is maintained in extension to minimize substitution by the flexor pollicis longus muscle (Fig. 2-20).

Figure 2-19 Adductor pollicis (C8, T1) assessment: Test this muscle by having the patient adduct a straightened thumb in the plane parallel to the palm. Try to separate the thumb from the lateral border of the palm. Alternatively, you may place your index finger between his or her thumb and lateral palm, applying resistance as the thumb is adducted (shown).

Figure 2-20 Flexor pollicis brevis (C8, T1) assessment: Although not a very useful muscle to test because of its dual innervation (median and ulnar nerves), some weakness compared with the other side may be seen with ulnar lesions. To test this muscle, the patient flexes the thumb’s metacarpal-phalangeal joint, while the interphalangeal joint is maintained in extension to minimize substitution by the flexor pollicis longus muscle.

Martin–Gruber and Riche–Cannieu Anastomoses

As mentioned in the median nerve chapter, the median and ulnar nerves may communicate with each other in the forearm between the anterior interosseus nerve and the ulnar nerve (Martin–Gruber anastomosis). A second communication may occur in the deep palm between the thenar motor branch of the median nerve and the deep motor division of the ulnar nerve (Riche–Cannieu anastomosis). It is through these two potential routes of communication that minor or major shifts in motor innervation of the hand may occur.

The Riche–Cannieu anastomosis, although anatomically present in the majority of patients, does not always communicate axons that shift innervation between median and ulnar nerves. However, when transfer does occur, this connection most commonly either returns thenar innervation that was transferred to the ulnar nerve in the forearm via the Martin–Gruber anastomosis, or acts as a conduit for the median nerve to innervate all the lumbricals, not only the first two. The important principle to remember is that when strange patterns of deficits occur following median or ulnar nerve injury, one should consider these potential communications when deciding if an injury is complete or incomplete.

Sensory Innervation

Sensory Innervation

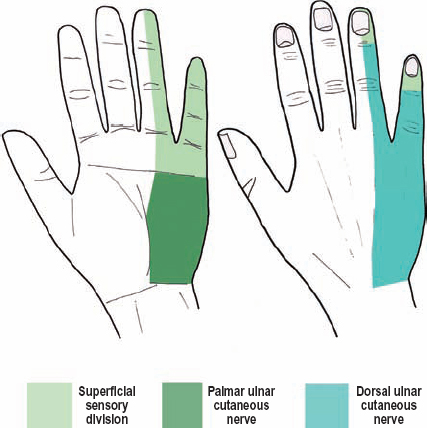

Excluding the medial brachial and antebrachial cutaneous nerves, which originate from the medial cord (described previously), the ulnar nerve has three sensory branches. These branches provide sensory innervation to the medial one third of the hand (Fig. 2-21). The dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve pierces the antebrachial fascia just proximal to the dorsomedial wrist. It crosses the wrist and ramifies to innervate the dorsomedial one third of the hand. It also innervates the dorsum of the fifth and medial one half of the fourth digits. The skin under and surrounding the fingernail is innervated however, by the superficial sensory division of the ulnar nerve, whose branches arise from the volar surface. Sensory testing for the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve should take place on the dorsal surface of the medial third of the hand.

The palmar ulnar cutaneous nerve enters the subcutaneous space of the hypothenar eminence and provides sensory innervation to this area. This nerve innervates the whole medial one third of the palm. Because of sensory territory variations, however, the best area to test this nerve’s function is on the hypothenar eminence.

The superficial sensory division of the ulnar nerve, besides innervating the palmaris brevis muscle, is a pure sensory nerve. It carries sensation from the volar surface of the fifth and medial one half of the fourth digits, including the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanges. The digital nerves carry sensation from the fingers to the superficial sensory division. The optimal area to test autonomous sensation for this nerve is on the volar aspect of the fifth digit.

Frequent variation in sensory territories between these three ulnar branches occurs. For example, the palmar ulnar cutaneous nerve can only cover the proximal hypothenar eminence, with the superficial sensory division covering the remaining medial, volar surface of the palm. Another common variation is for the median (more common), or ulnar nerve, to carry all the sensory fibers from the fourth digit.

Frequent variation in sensory territories between these three ulnar branches occurs. For example, the palmar ulnar cutaneous nerve can only cover the proximal hypothenar eminence, with the superficial sensory division covering the remaining medial, volar surface of the palm. Another common variation is for the median (more common), or ulnar nerve, to carry all the sensory fibers from the fourth digit.

Figure 2-21 Sensory innervation from the ulnar nerve. The ulnar nerve has three sensory branches. These branches provide sensory innervation to the medial one third of the hand.

Clinical Findings and Syndromes

Clinical Findings and Syndromes

In contrast to the median nerve, where entrapment usually occurs at the wrist and rarely in the proximal forearm/elbow, for the ulnar nerve the opposite is true: It is compressed most commonly at the elbow, and rarely at the wrist.

The Arm

Complete Palsy

Ulnar nerve palsies in the arm region are usually caused by trauma, including gunshot wounds, lacerations, and blunt injuries. Because of its close proximity to the median nerve and brachial artery, concomitant injury to these three structures may occur. As with the median nerve, the ulnar nerve may be compressed by using a crutch or hanging the arm over a chair (Saturday night palsy).

A complete ulnar nerve lesion is quite devastating, considering the loss of fine, coordinated hand movements. To begin, a severe ulnar lesion causes loss of sensation in the hypothenar eminence (palmar ulnar cutaneous branch), the volar surface of the fifth and half of the fourth digits (superficial sensory division), and the dorsomedial one third of the hand and fingers (dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve). However, if sensory abnormalities extend more than 2 cm proximal to the wrist crease one should alternatively consider involvement of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, and therefore the medial cord of the brachial plexus or C8/T1 nerve roots. Regarding motor loss, wrist flexion will be weak and only in a radial direction, from the unopposed contraction of the flexor carpi radialis (median innervated). The distal phalanges of the fourth and especially the fifth digits will not flex secondary to partial flexor digitorum profundus weakness. Marked hand intrinsic weakness occurs, with the only residual function provided by the median nerve innervated thenar muscles. Muscle wasting can eventually be seen, including the hypothenar eminence, the dorsal interosseous muscles, and even the thenar eminence secondary to wasting of the large adductor pollicis muscle. There is loss of finger abduction and adduction, from paralysis of both the dorsal and palmar interossei, respectively. However, as mentioned earlier, some finger abduction or adduction can still occur because of substitution by the long finger extensors and flexors.

Ulnar claw hand is when opening the hand, there is hyperextension at the metacarpal-phalangeal joints in the fourth and especially the fifth digits, along with partial flexion of both interphalangeal joints in these two fingers (Fig. 2-22). Ulnar claw hand results from a loss of function in the third and fourth lumbricals, along with paralysis of the interossei and flexor digit minimi, which causes flexion weakness at the metacarpal-phalangeal joints. The extensor digitorum communis (radial nerve) becomes unopposed, thereby placing these two metacarpal-phalangeal joints in hyperextension. Despite paralysis of the flexor digitorum profundus in these two digits, its tendons are still placed on tension. This is because of both finger’s hyperextension, as well as from residual tone in this muscle secondary to its median nerve innervated portion. Furthermore, when a severe or complete ulnar nerve lesion occurs distal to the flexor digitorum profundus (i.e., a lesion that spares this muscle), the degree of claw hand is worse because even more unopposed distal finger flexion occurs. Without proper physical therapy, ulnar claw hand may become permanent, secondary to contractures.

Figure 2-22 Ulnar claw hand (patient’s left). The ulnar claw hand occurs when opening the hand, there is hyperextension of the metacarpal-phalangeal joints in the fourth and especially the fifth digits. Both interphalangeal joints are also partially flexed in these two fingers. Atrophy of the first dorsal interosseous muscle is evident on the dorsal view (bottom). The patient’s normal right hand is shown for comparison.

Wartenburg’s sign is when the fifth digit is slightly more abducted when compared with the normal hand. This occurs because the third palmar interosseous muscle, which adducts the fifth digit, is paralyzed; the unopposed action of the extensor digiti minimi and extensor digitorum communis of the radial nerve causes the finger to rest in a slightly more-abducted position.

Froment’s sign can be elicited when the patient is asked to pull apart a piece of paper held between the complete volar surface of each straightened thumb and closed fist (Fig. 2-23). In the affected hand, the adductor pollicis is weak and thumb adduction does not occur. Instead, the interphalangeal joint of the affected thumb flexes to hold the paper through contraction of the flexor pollicis longus (median innervated).

Figure 2-23 Froment’s sign. When the adductor pollicis is weak, thumb adduction does not occur. Instead, contraction of the flexor pollicis longus muscle substitutes for this movement by flexing the interphalangeal joint of the thumb. The upper photograph illustrates a bilateral Froment’s sign when a subject attempts to pull apart a piece of paper. The lower figure reveals a Froment’s sign when the patient is instructed to hold a straightened thumb against the lateral margin of the hand.

Arcade of Struthers

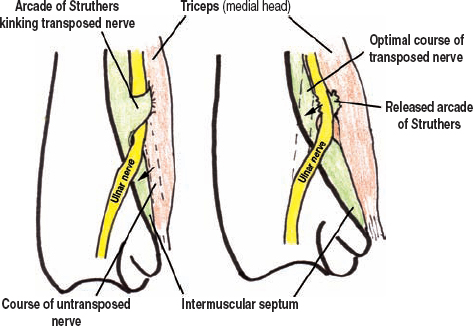

Once piercing the intermuscular septum about halfway down the arm, the ulnar nerve runs along, and slightly within, the medial head of the triceps. In approximately 50% of the population, an arcade of fascia, the arcade of Struthers, extends over the ulnar nerve from the intermuscular septum to the superficial surface of the medial head of the triceps. This arcade is a few centimeters in length and occurs approximately 8 cm proximal to the elbow.

The arcade of Struthers, in fact, does not cause primary ulnar nerve compression. Instead, it has been posited as the reason why some ulnar nerve transpositions at the elbow fail; the arcade of Struthers, when present and not transected during the original transposition surgery, may tether the relocated ulnar nerve, which leads to compression and recurrent symptoms (Fig. 2-24).

Figure 2-24 Arcade of Struthers compressing a transposed ulnar nerve. It is purported that if this fascial arcade is present and not transected during the original transposition surgery, then a medially transposed nerve at the elbow can become tethered at the arcade of Struthers leading to a new area of compression and recurrent symptoms.

The Elbow

Olecranon Notch

Compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow is a common entrapment, second only to carpal tunnel syndrome (Fig. 2-25). It usually presents with sensory changes in the fifth and fourth digits, including hyperesthesia, hypesthesia, and paresthesias. At first, these symptoms are intermittent, often induced by prolonged forearm flexion or direct compression of the ulnar nerve in the postcondylar grove. Ask about repetitive actions and a history of mild trauma. These sensory symptoms can occur at night if one sleeps with the arm in flexion or if the elbow lies on a hard surface when the forearm is extended and supinated, thus exposing the ulnar nerve to compression. Although not as common as with carpal tunnel syndrome, symptoms from ulnar nerve compression at the elbow can also wake the patient up at night. Abnormal light touch and vibration sense may be evident on examination. Provocative maneuvers, like flexing the forearm for a minute, may precipitate symptoms. The patient should also repetitively flex the elbow while you palpate the ulnar nerve in the postcondylar groove to rule out “snapping” or dislocation of either the ulnar nerve or medial triceps tendon, both of which can cause ulnar nerve irritation at the elbow. One must keep in mind, however, that the majority of patients with prolapsing ulnar nerves are asymptomatic.

Figure 2-25 Compression at the elbow. The most common point of ulnar nerve damage, as evidenced by intraoperative nerve action potential recordings, is at the postcondylar groove just proximal to its covering aponeurosis. Other points of possible ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow include between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris (cubital tunnel syndrome), and by Osborne’s fascia, when present.

As nerve damage progresses, patients usually report numbness that is more persistent. They report pain in the postcondylar region often radiating down the medial forearm to the hand. A Tinel’s sign at the postcondylar groove may be present. With more nerve damage, patients begin to have weakness in the ulnar innervated hand intrinsic muscles. They may report clumsiness with fine hand movements, like buttoning buttons or using a pen. With moderate to severe damage, two-point discrimination can also be affected. To ascertain subtle hand intrinsic weakness, one can observe the following finger movements: rapid thumb to fingertip touching (observe slowing and lack of precision), synchronous digit flexion and extension (look for early claw hand), and if available, power grip testing (usually decreased up to 80% with ulnar palsies).

With more severe and chronic compression, persistent numbness, hand intrinsic weakness, ulnar nerve tenderness at the elbow, and muscular atrophy may be present. When atrophy occurs, it is most readily noted at the hypothenar eminence and first dorsal interosseous muscle. Median nerve innervated hand intrinsics (e.g., abductor pollicis brevis) should be normal, or else a C8/T1 spinal nerve/lower trunk lesion may be present (e.g., neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome). Ulnar claw hand, Wartenberg’s sign, and Froment’s sign are all usually present in severe, chronic cases. Despite branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris often originating from the ulnar nerve distal to the postcondylar groove, weakness of this muscle in cubital tunnel syndrome is rare. This has been attributed to the fact that the sensory and hand intrinsic fibers in the ulnar nerve at the elbow are more superficial, and perhaps, more prone to irritation. If flexor carpi ulnaris weakness is present or occurs early in the presentation, a lesion more proximal to the postcondylar groove should be considered.

The most common point of ulnar nerve damage, as evidenced by intraoperative nerve action potential recordings, is at the postcondylar groove just proximal to its covering aponeurosis. Other points of possible ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow include between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris (cubital tunnel syndrome) and by Osborne’s fascia, when present.

Tardive ulnar palsy refers to a person with late-onset ulnar nerve compression at the elbow following an elbow fracture years earlier. In these patients, the fracture causes a capitus valgus deformity at the elbow (with the elbow extended, the forearm is not straight in relation to the humerus, but instead angles laterally). This anatomical situation increases tension on the medially located ulnar nerve (by increasing the distance it must travel), thereby predisposing it to compression at the elbow. On a separate note, the anconeus muscle, which runs between the medial epicondyle and olecranon in some patients, may also cause ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow. The most frequent operative positioning injury affects the ulnar nerve at the elbow.

Tardive ulnar palsy refers to a person with late-onset ulnar nerve compression at the elbow following an elbow fracture years earlier. In these patients, the fracture causes a capitus valgus deformity at the elbow (with the elbow extended, the forearm is not straight in relation to the humerus, but instead angles laterally). This anatomical situation increases tension on the medially located ulnar nerve (by increasing the distance it must travel), thereby predisposing it to compression at the elbow. On a separate note, the anconeus muscle, which runs between the medial epicondyle and olecranon in some patients, may also cause ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow. The most frequent operative positioning injury affects the ulnar nerve at the elbow.

The Forearm

Flexor-Pronator Fascia

Although exceedingly rare, the ulnar nerve may be irritated by a thickened flexor-pronator fascia. Compression by this structure would occur in the proximal to mid-forearm (approximately 5 cm distal to the medial epicondyle), where the ulnar nerve passes between the flexor carpi ulnaris and the flexor-pronator muscle mass. The fascia of this latter muscle mass may be excessively thickened, thereby predisposing one to compression. Although a clear syndrome has not been reported, repetitive forearm pronation and wrist flexion is thought to be associated with this form of compression.

The Dorsal Ulnar Cutaneous Nerve

Occasionally, the dorsal ulnar cutaneous branch may be compressed or transected as it leaves the ulnar nerve and passes to the dorsum of the wrist between the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon and the ulna. Ulnar fractures or repairs, lacerations, and/or blunt trauma may be causative. The patient presents with numbness or hypesthesia in the dorsomedial one third of the hand in this branch’s anatomical distribution. With some lesions, a Tinel’s sign can be elicited when tapping on the medial border of the ulna approximately 5 cm proximal to the wrist.

The Wrist

Guyon’s Tunnel

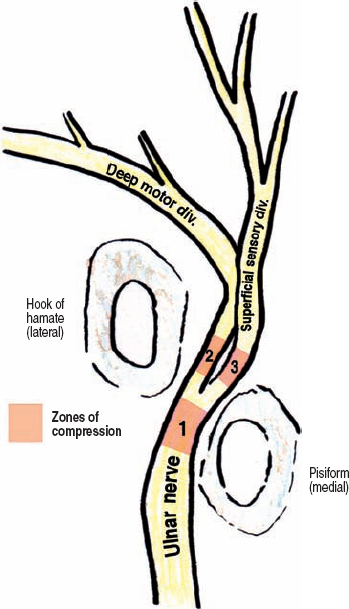

Ulnar nerve compression at the wrist is rare. Nonetheless, based on the ulnar nerve’s branching pattern in Guyon’s tunnel, three “zones” of compression have been described: zone, compression of the ulnar nerve prior to its division in Guyon’s tunnel; zone 2, compression of only the deep motor division; and zone 3, compression of only the superficial sensory division (Fig. 2-26).

Zone 1 lesions affect the ulnar nerve before it divides. The etiology is usually a fracture or ganglion cyst compressing the nerve in the proximal two thirds of Guyon’s tunnel. Sensory loss occurs on the volar surfaces of the fifth and medial half of the fourth fingers, including the nail beds. Sensation to the hypothenar eminence is commonly spared because the palmar ulnar cutaneous nerve is unaffected. Patients with zone 1 compression can have intrinsic hand muscle weakness including a claw hand, Wartenberg’s sign, and Froment’s sign. The claw hand can be quite severe because innervation to the flexor digitorum profundus is preserved.

Zone 2 lesions compress only the deep motor branch, and therefore no sensory loss occurs. The motor deficits are similar to a zone 1 lesion. To confirm that the superficial sensory division is intact, one may check for a palmaris brevis sign, which is simply observing the contraction of the palmaris brevis (Fig. 2-12). Innervation of this small muscle is from the proximal superficial sensory division, and therefore if this muscle contracts, one knows that this division is at least partially functioning. Zone 2 lesions are usually caused by ganglion cysts. Occasionally, just the hypothenar branch from the deep motor division is injured, causing isolated weakness of the hypothenar muscles.

Figure 2-26 Zones of compression in Guyon’s tunnel. Based on the ulnar nerve’s branching pattern in Guyon’s tunnel, three “zones” of compression have been described: zone 1, compression of the ulnar nerve prior to its division in Guyon’s tunnel (most common); zone 2, compression of only the deep motor branch; and zone 3, compression of only the superficial sensory division (least common).

Zone 3 lesions affect only the superficial sensory division, and are the least common variety of ulnar entrapment at the wrist. A reliable area to test for sensory loss is on the volar surface of the fifth digit. All motor function is usually spared and the palmaris brevis sign may be absent (no contraction). A distal ulnar artery thrombosis or aneurysm may be causative.

Ulnar nerve compression at the wrist can also be secondary to direct pressure. This can occur from prolonged writing, using a computer or mouse, and from riding a bicycle. These lesions present with a combination of motor and sensory symptoms and usually respond well to conservative treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree