The Economics of Spondylolysis

Rikke Soegaard

Finn Bjarke Christensen

The methodology and adaptation of health economics has emerged rapidly over the past decades. From cost-of-illness studies, which describe the economic impact of a disease, through cost-benefit, cost-utility, and cost-effectiveness evaluations, which analyze costs against consequences and thus provide a decision-analytic approach in determining which intervention that provides the best value for money. The aim of the present chapter is to (a) introduce the basics of health economic methodology relevant to spondylolysis, (b) present a selection of recent studies applying this methodology, and (c) describe the opportunities in applied health economics as seen from Denmark.

A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO THE METHODOLOGY

The Cost-of-Illness Approach

The burden of a disease to society can be estimated in economic terms by the cost-of-illness approach. Although this method has substantial limitations because it returns only an absolute point measure of costs, which is rarely comparable between societies or repeated measurements, this approach can be useful to visualize potentials for research efforts or simply to awaken politicians.

Basic considerations of a cost-of-illness study are (a) whether to adapt prevalence-based or incidence-based data, (b) whether to take a top-down or bottom-up approach, and (c) which cost categories to include. Costs are defined by “opportunity costs,” not to be confused by expenditures, which are only relevant to financial analyses (e.g., budget impact analyses). An opportunity cost reflects the value of a resource in the best alternative use (e.g., should a surgeon choose to perform an operation free of charge, the cost would still be the value of the surgeon’s time spent although the expenditure for salary would be zero).

In conducting or evaluating a cost-of-illness study, all consequences associated with the disease should be identified, measured, and valuated. Hence, the costs occurring in the health care sector, other sectors, and the patient and family sphere (e.g., transportation for treatment activities, medication, time spent, etc.) should be included. In practice, however, cost categories most often comprise the costs directly associated with the disease and occurring in the health care sector (so-called direct costs of prevention, diagnostics, treatment, and rehabilitation), production loss from absenteeism or disability, and finally, the value of informal care.

Cost-Effectiveness, Cost-Utility, and Cost-Benefit Approaches

Because of a lack of consensus regarding the definition of economic evaluation several studies are indexed as economic evaluations although in practice they are cost descriptions or cost analyses.

Drummond defines an economic evaluation from two criteria: (a) there should be a comparison of two or more alternatives and (b) both costs (inputs) and consequences (outputs) of the alternatives should be examined (1). If one of these criteria is not fulfilled, the evaluation is considered partial and should be termed “description” or “analysis” instead of “evaluation.”

The main purpose of economic evaluation is to provide a decision-analytic foundation for the decision makers who prioritize efficiency in health care. Very often, the experimental intervention at hand is an intervention that is obviously both more effective and more costly than the usual regimen. Thus, we want to document the cost-effectiveness (alternatively cost-utility or cost-benefit) of the new intervention to establish an argument for implementing it in everyday clinical practice.

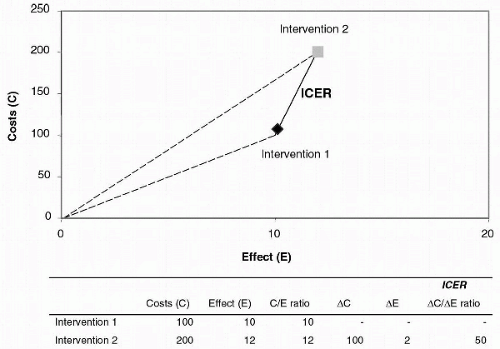

In practice, we have to identify, measure, and valuate all resources consumed in relation to the interventions at hand. This measure of total costs is put up against consequences and, thus, a ratio of cost-consequences is obtained. The higher the ratio between costs and consequences, the more efficient is the intervention. However, the meaningful ratio one should be concerned about is the incremental cost-consequence ratio, which describes the additional costs and the additional consequences one intervention imposes over another. The argument here is, of course, that we do not develop an intervention from scratch but rather, we enhance or extend the usual regimen to gain additional effect. The question is: Are we willing to accept the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for obtaining the additional effect? Most often, the average cost-effectiveness ratio (the first effect units) is far more attractive than the incremental (the last effect units). For example, the first 10 points gain in a scale of function ability or pain is obtainable by an average of x per point whereas the following point is obtainable by a cost of multiple times the x per point. The principle of the average and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) is illustrated in Figure 22.1.

TABLE 22.1. Four methods for economic evaluation | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

To set up an economic evaluation, the first step is to decide upon the perspective relevant to the purpose of the study (that of the recipients of the study, who are often the decision makers). From a theoretical viewpoint, it is difficult to vote against a societal perspective because the consequences are most often not isolated within a department, a hospital, or the health care sector. However, societal costs are often rather difficult to estimate with reasonable precision. The solution often seen is to report both the health care sector perspective (costs occurring in the health care sector) and the societal perspective (health care sector costs plus societal costs of production loss, patient costs, and family costs).

The method used for measuring consequences (output) distinguishes among the types of economic evaluation as illustrated in Table 22.1. The evaluation is defined as a cost-effectiveness when consequences are measured in physical units, which is most often the case in the field of spine research evaluation, by means of e.g., using the Dallas Pain Questionnaire (2), Low Back Pain Rating Scale (3), Oswestry Disability Index (4), SF-36 Health Survey (5) or global health assessments. Should consequences be expressed as generic health-related quality-of-life measures (e.g., quality-adjusted life years, QALYs), the evaluation is defined as a cost-utility. Finally, if consequences are measured in monetary units that reflect the patient’s willingness to pay for the consequences of the intervention provided, the evaluation is defined as cost-benefit. Put another way, the choice is a question of comparability between studies; cost-effectiveness measures allow for disease-specific comparisons (if there is consensus about effect measures), whereas the other types of measures are generic. In economic evaluation, hybrid types are often seen. Especially, a fourth type is commonly used: the cost-minimization analysis. This method is relevant if the consequences of two or more interventions have already been compared and do not differ significantly although the resources needed to accomplish the output differ. Here, the purpose is to determine which intervention demands the least costs to accomplish the output.

In conclusion, the cost-effectiveness evaluation allows for allocation of resources within one specific field (e.g., conservative versus surgical treatment in chronic low back pain), and the cost-utility approach allows for allocation within different fields of health (e.g., hip replacements versus kidney transplants), whereas the cost-benefit approach allows for allocation among different sectors in society (e.g., traffic controls versus trauma facilities). Important to recognize, however, is the fact that these studies still leave it to the decision makers to prioritize ethics and, especially in relation to the cost-effectiveness approach, to put a value on the health effects attained. Given these limitations, economic evaluations are useful tools in determining which interventions offer the best value for money, and as this discipline emerges, the methodology is continuously being improved. Because of increasing health care costs and scarcity of resources, governments and societies are increasingly demanding evidence not only for the clinical effect, but no less for

the cost-effectiveness, of various health treatments and procedures—a fact that is underlined by the World Health Organization in the text of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 announcement (6,7). Hence, economic evaluation is a need rather than an option in modern health scientific research.

the cost-effectiveness, of various health treatments and procedures—a fact that is underlined by the World Health Organization in the text of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 announcement (6,7). Hence, economic evaluation is a need rather than an option in modern health scientific research.

APPLIED HEALTH ECONOMICS IN SPONDYLOLYSIS

Applied Cost-of-Illness Methodology

Several studies have investigated the economic burden of back pain to society (11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18). In a recent review by Maetzel and Li, the socioeconomic burden of low back pain is concluded equal to the burdens of depression, heart disease, or diabetes (19). Another significant conclusion by Maetzel and Li is that the costs of low back pain are characterized by a heavily right-skewed distribution. Hence, those 5% to 9% of patients who manifest chronic pain account for 65% to 85% of costs (19).

Maniadakis and Gray (16) have conducted a cost-of-illness study in the United Kingdom concluding that the direct medical costs of back pain amount to US$4.2 billion and the associated production loss and value of informal care amount to US$27.5 billion (1998 prices). In total, these figures are equal to 1.43% of the British gross national product. This state-of-the-art study is probably one of the most comprehensive to date and takes advantage of a national survey of 6,000 adults with regard to both prevalence of back pain and related service utilization. Service utilization was validated by relevant sources (e.g., registries and statistics of medical societies), and national cost estimates per item were multiplied (e.g., 7.5 million consultations with a surgeon at US$36 per consultation) (16). The estimation of production loss however, is somehow controversial. Maniadakis and Gray faced the methodologic discrepancies by presenting two different, but commonly used approaches (a) the human capital method, in which production loss is estimated from days of absenteeism and disability multiplied by the earning potential of the person not contributing to production, and (b) the more conservative friction method, in which sick leave of a person is only considered significant if no other person can replace him or her, and thus only a limited period of friction is multiplied by the earning potential. Maniadakis and Gray found that the human capital approach yielded the estimate of US$27.5 billion and the friction approach yielded the estimate of US$12.9 billion. Health economists do not agree on which is the correct approach, and the approach chosen may depend on the purpose of the study.

A critical point of the Maniadakis and Gray study is reflected in the study by Lou et al. (15), who investigated direct medical costs of back pain in the United States. Lou et al. conclude, upon a regression analysis, that direct medical costs due to back pain comprise US$90.7 billion, but of this total only US$26.3 billion are incremental costs related to back pain. Evidently, caution should be taken in concluding that the full resource consumption in back pain patients is allocatable solely to the disease of back pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree