The External Carotid Artery and Extracranial Circulation

Key Points

The anatomy of the extracranial circulation is in many ways more challenging than that of the intracranial system. Proficiency in this domain is essential for the prevention of severe complications from endovascular procedures, including tissue necrosis, cranial nerve injury, and blindness.

Anastomotic connections between the extracranial vessels and the intracranial circulation are an ever-present danger during extracranial embolizations and should always be evaluated before proceeding.

The branches of the external carotid system are named according to their respective territories without regard to the site of origin of the vessel or pattern of division of the external carotid artery. Certain patterns of branching can be seen as characteristic and, when present, will help in identification of named vessels. The capacity of the external carotid artery to compensate for a restriction on flow in one branch by developing collateral flow through a number of other pathways becomes a major consideration in interventional procedures. The preocclusion angiogram does not necessarily indicate which anastomoses are lying dormant waiting to assume a greater hemodynamic role. In a vascular field being embolized, potential anastomoses with dangerous collateral pathways to the internal carotid artery or ophthalmic artery may not fill during the initial part of the procedure. However, as the outflow from the field becomes restricted by progressive embolization, previously unseen pathways emerge, turning what may have initially seemed a safe embolization procedure into a dangerous one.

Therefore, in learning the anatomy of the external carotid system, flexibility must be incorporated into one’s conception of the arborization of the vessel. The territory of destination is the factor that determines the nomenclature of a vessel; its relationship to bony structures and tissue planes helps to confirm its identity. A vessel’s location and identity guide the interpreter toward an awareness of the potentially dangerous anastomoses that may be relevant. One’s thinking should also take reckoning of nonvisualization of supply to a particular area. An assumption that the supply is coming from an alternative source must be entertained.

On the AP view of the external carotid artery, most of the proximal vessels are superimposed on the outer aspect of the face in an area that is prone to technical overexposure. For these reasons, and because most of the branches of the external carotid artery run in an AP plane, most images of the proximal external carotid artery branches are depicted in the lateral plane. An important component for understanding the angiographic anatomy of the external carotid artery is the tissue plane in which a particular vessel lies. Vessels that cross one another on the angiographic image without anastomosing lie in different anatomic planes. Vessels that appear to cross a bony barrier, such as the skull base, without a deflection in their course, must lie in a more superficial tissue plane.

Branches of the External Carotid Artery

Superior Thyroidal Artery

In approximately 75% of patients, the external carotid system arises as a common trunk in an anteromedial relationship to the internal carotid artery between C3 and C5. It usually divides quickly, giving an inferiorly directed superior thyroidal artery as the first branch (Figs. 17-1 and 17-2). In the normal state, this is a small, tapered vessel projecting anteriorly and medially with a number of branches to the larynx and related structures, thyroid gland, and parathyroid glands. If injected directly, the normal thyroid gland will give a discernible dense blush. The superior thyroidal artery may arise as a common trunk with other branches of the external carotid artery or from the common carotid artery. There are rich anastomoses within and around the thyroid gland between the superior and inferior thyroidal arteries. The inferior thyroidal artery is a branch of the thyrocervical trunk or, less commonly, of the vertebral artery, subclavian artery, or common carotid artery. The thyroid ima artery arises from the aortic arch.

Ascending Pharyngeal Artery

The ascending pharyngeal artery is usually a long, needle-thin vessel arising from the posterior aspect of the proximal external carotid trunk. Variant sites of origin include a

common trunk with the occipital artery or origin from the internal carotid artery.

common trunk with the occipital artery or origin from the internal carotid artery.

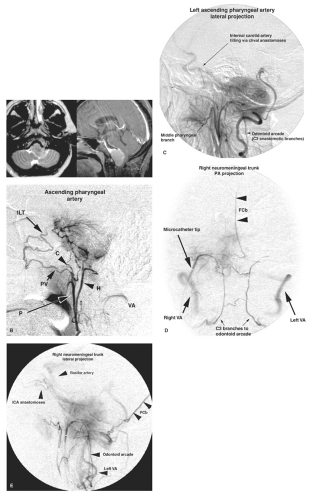

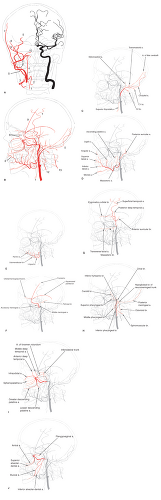

Figure 17-1. (A–D) External carotid artery. A and B: PA and lateral illustrations of the external carotid artery circulation, while the internal carotid artery is illustrated on the anatomic left side for reference. (1, superior thyroidal artery; 2, lingual artery; 3, facial artery; 4, ascending pharyngeal artery; 5, occipital artery; 6, posterior auricular artery; 7, superficial temporal artery; 8, deep temporal artery; 9, middle meningeal artery; 10, accessory meningeal artery; 11, internal maxillary artery; 12, ascending cervical artery (from thyrocervical trunk); 13, deep cervical artery from the costocervical trunk.) B: Template for subsequent illustrations of individual arteries. C: The superior thyroidal artery and occipital artery are highlighted. The C1 and C2 branches of the occipital artery are indicated, as are the stylomastoid and transmastoid branches of the occipital artery. The stylomastoid and transmastoid branches may arise from other external carotid branches. The occipital artery may also give rise frequently to the neuromeningeal trunk, which is illustrated in Figure 17-1H in its more common form as a branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery. The occipital artery is illustrated giving rise to the artery of the falx cerebelli. This dural artery more commonly arises from the vertebral artery or posterior inferior cerebellar artery. D: The facial artery and posterior auricular artery are highlighted. The branches of the facial artery are labeled. The shepherd’s hook appearance of the ascending palatine artery illustrated here is characteristic of this vessel. It is often this curve that catches one’s attention when this territory is filled via collateral flow. In (A), notice the superficial course of the posterior auricular artery relative to the occipital artery. They may occasionally arise together as a common trunk. The curve of the posterior auricular artery in (A) is characteristic of the vessel. It can be difficult to cannulate if the external carotid artery proximal to that point is tortuous. (E–H) E: The lingual artery is highlighted. The dorsal artery of the tongue with its ranine branches is a characteristic feature. Its circulation at the floor of the mouth and around the submandibular gland is in variable balance with the adjacent branches of the facial artery. F: The middle meningeal artery is highlighted. It is illustrated here with a common exocranial trunk shared by the accessory meningeal artery. However, the accessory meningeal artery may have a separate origin from the internal maxillary artery. The branches of the middle meningeal artery are indicated (petrous branch (a dangerous vessel during embolization as it can supply the vasa nervorum of the VII nerve in the middle ear); lacrimal branch to the orbit (variable); frontal branch; squamous branch). G: The superficial temporal artery and related arteries are highlighted. These include the posterior deep temporal artery, anterior auricular artery, transverse facial artery, and masseteric branches of the latter. The arrow indicates the characteristic intersection of the transverse facial artery and the underlying buccal artery. The zygomatico-orbital branch of the superficial temporal artery is indicated because this is an important branch for superficial temporal artery to ophthalmic artery reconstitution. When the zygomatic branch is prominent, the transverse facial artery is not well seen, and vice versa. H: The lateral appearance of the ascending pharyngeal artery is illustrated. The main branches of the ascending pharyngeal artery are labeled (see text for discussion). (I–J) I: Various branches and anastomotic relations of the internal maxillary artery are highlighted (anterior deep temporal; middle deep temporal; artery of the foramen rotundum connecting to the inferolateral trunk, lesser descending palatine artery supplying the soft palate; greater descending palatine artery; sphenopalatine arteries; infraorbital artery). The deep temporal arteries are sometimes described as having a “pseudomeningeal appearance,” which refers to their smooth straight course. However, they do not deflect at the skull base, as is the case of the middle meningeal artery. Furthermore, they have a very straight superficial course on the PA view (see A). The tortuous appearance of the artery of the foramen rotundum is very characteristic as it directs itself toward the floor of the sella. This is one of the most important anastomoses in internal maxillary artery embolization. The infraorbital artery is easy to recognize. It has the shape of an upturned boat hull, giving a small orbital branch directed superiorly as indicated. The lateral (short) sphenopalatine arteries conform to the curves of the turbinate bones. J: More branches of the internal maxillary artery are labeled (pterygovaginal artery; inferior alveolar (dental) shown here arising from a common trunk with the middle deep temporal artery, a common variant; antral branch arising as a common alveoloantral trunk with the superior alveolar artery, buccal artery connecting the facial and internal maxillary arteries). |

The ascending pharyngeal artery is directed superiorly in a straight course toward the posterior nasopharynx, appearing to lie in front of or on the vertebral column on the lateral view, and in a position medial to the main external carotid trunk on the AP view. It is an important supply route to the pharynx, dura, and lower cranial nerve foramina of the skull base, and to the middle ear. The ascending pharyngeal artery usually divides into a number of identifiable branches or trunks, several of which have important collateral anastomoses to intracranial vessels:

Pharyngeal trunk

Superior pharyngeal branch

Middle pharyngeal branch

Inferior pharyngeal branch

Neuromeningeal trunk

Hypoglossal branch

Jugular branch

Inferior tympanic artery

Musculospinal artery

The configuration is prone to variability. The pharyngeal trunk may not have all three branches present in an identifiable form. The inferior tympanic artery may be a branch of one of the other trunks. Some components or the entire neuromeningeal trunk may be a branch of the occipital artery.

The pharyngeal branches of the ascending pharyngeal artery can be most easily seen on the lateral view anterior to the ascending pharyngeal artery itself and are described and frequently seen as three in number: Superior, middle, and inferior (Fig. 17-3). These can be thought of as corresponding with the nasopharynx (Eustachian tube region), oropharynx (and soft palate), and hypopharynx, respectively.

The superior pharyngeal branch gives an important intracranial anastomosis through the foramen lacerum, the carotid branch, which anastomoses with the recurrent laceral branch of the inferolateral trunk of the internal carotid artery. In the posterior nasopharynx, the superior pharyngeal branch anastomoses with the internal maxillary artery system via the pterygovaginal artery. The superior pharyngeal branch also makes variable anastomoses with pharyngeal branches of the accessory meningeal artery and with the mandibular artery, when present.

The neuromeningeal trunk is also a long straight artery diverging posteriorly from the pharyngeal trunk, ascending to overlap the foramen magnum on the lateral view. Its major posteriorly directed branches are the hypoglossal artery and the jugular artery, which access the endocranial space through the respectively named foramina. The hypoglossal artery is the more medial of the two branches on the AP view.

The hypoglossal branch of the neuromeningeal trunk is an extremely important vessel. Its normal function is to supply the neural structures of the hypoglossal canal and a variable dural territory in the posterior fossa. It may give rise to the artery of the falx cerebelli, the posterior meningeal artery, or rarely, the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. Its important anastomotic branches can be divided into those that ascend along the back of the clivus, and those that descend through the foramen magnum and along the back of the body of the C2 vertebral body where it meets the C3 branch of the ipsilateral vertebral artery. This bilateral connection between the vertebral artery and the ascending pharyngeal artery behind the body of C2 is called the arcade of the odontoid process.

Clival branches of the hypoglossal branch of the neuromeningeal trunk ascend the dorsum of the clivus to meet with medial clival branches from the meningohypophyseal trunk or equivalent internal carotid artery hypophyseal branches (Fig. 17-3). Thus, opacification of the posterior aspect of the pituitary gland can be seen occasionally during superselective injections of the ascending pharyngeal artery. More importantly, this route of collateral flow from the ascending pharyngeal artery to the internal carotid artery can form the basis for dangerous anastomoses during embolization. Alternatively, flow through this route may be visible on the lateral angiogram, allowing reconstitution of the cavernous internal carotid artery. In this manner, clival branches of the neuromeningeal trunk may simulate the “string sign” for persistent internal carotid artery flow in the setting of internal carotid artery occlusive disease.

The jugular branch of the neuromeningeal trunk supplies the neural structures and adjacent dura of the jugular foramen. It is prominently seen in the setting of vascular tumors, such as glomus jugulare, in the region of the jugular foramen. In the normal state, it may also send branches anteromedially toward the Dorello canal containing cranial nerve VI. It anastomoses in this region with lateral clival branches of the internal carotid artery. Dural branches of the jugular branch of the neuromeningeal trunk directed toward the sigmoid sinus may have prominent anastomoses with dural branches of the middle meningeal artery and transosseous dural branches of other sources from the external carotid artery.

The inferior tympanic artery is usually a tiny vessel and steers a middle course between the neuromeningeal and pharyngeal trunks on the lateral view. It may arise from either trunk. It gains access to the middle ear via the inferior tympanic canaliculus, which it shares with the Jacobson branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve. It is therefore prominently involved in glomus tympanicum tumors. Within the middle ear, the inferior tympanic artery anastomoses with:

The stylomastoid branch of the occipital artery, which enters the middle ear via the canal of that name, running with the VII nerve.

The petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery.

The caroticotympanic branch of the internal carotid artery.

The musculospinal branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery is directed posteriorly and inferiorly on the lateral view at the level of the third cervical space. It supplies the cervical musculature, cranial nerve XI, and the superior sympathetic ganglion. It has important anastomoses to the ascending and deep cervical arteries and with the vertebral artery.

Lingual Artery

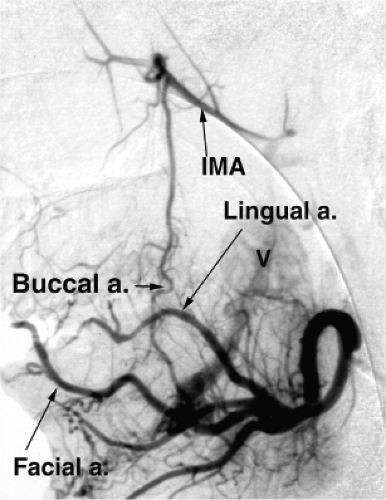

The lingual artery supplies the tongue, floor of mouth, and suprahyoid area. The largest branch is the terminal dorsal artery of the tongue, which is most easily identified on the lateral view. It extends toward the tip of the tongue and gives characteristic parallel ranine branches to the musculature of the tongue (Fig. 17-1E). Particle or other embolization in the lingual artery needs to be performed conservatively because the tongue has no alternative route of arterial supply, and iatrogenic tongue injuries can be very debilitating to the patient. In the floor of the mouth, the lingual artery has rich anastomoses with the facial artery. The facial artery territory in the region of the mandible, floor of mouth, and lower face may be supplanted completely by the lingual artery. The lingual artery contributes in varying degrees to the supply

of the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands. The lingual artery and facial artery may arise as a common linguofacial trunk. These two arteries are hemodynamically balanced; hypoplasia of one is compensated by dominance of the other.

of the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands. The lingual artery and facial artery may arise as a common linguofacial trunk. These two arteries are hemodynamically balanced; hypoplasia of one is compensated by dominance of the other.

Facial Artery

The facial artery arises more distally than the lingual artery, or they may share a common origin from the external carotid artery (Fig. 17-4). The usual musculocutaneous distribution of the facial artery is extensive, and its many branches have rich anastomoses to territories supplied by other external carotid artery branches. Therefore, when these other branches are prominent or “dominant,” the facial artery will be correspondingly smaller or hypoplastic. The facial artery usually arises medial to the angle of the mandible. To gain access to the facial structures outside the plane of the mandible, the facial artery must make an inferiorly and laterally directed loop to course around the body of the mandible. This point corresponds with the anterior edge of the masseter muscle insertion (Fig. 17-1D). To make this loop on the lateral projection, it must dip below the level of the lingual artery, creating potential confusion between the two vessels at this point.

The ascending palatine artery arises from the proximal deep segment of the facial artery or adjacent external carotid artery. It ascends toward the soft palate along the levator palati muscle with a very characteristic shepherd’s crook configuration. It anastomoses with the other arteries to the soft palate, particularly the middle branch of the pharyngeal trunk of the ascending pharyngeal artery, the lesser descending palatine artery from the internal maxillary artery, and the pharyngeal branch of the accessory meningeal artery. In cases of delayed post-tonsillectomy bleeding, this is the most likely site of injury due to necrosis or sloughing of the tonsillar bed.

The facial artery supplies the superficial facial structures, giving named branches to the submandibular gland, the submental foramen, the mandible (mental branch), the superior and inferior labial area, the cheek (jugal branches), and the ala of the nose (alar branch). It terminates as a nasoangular branch tapering along the lateral aspect of the bridge of the nose, or alternatively as a naso-orbital branch when directed toward the inner canthus of the eye.

The jugal vessels may arise as a common trunk or as separate anterior, middle, and posterior branches from the facial artery. The jugal branches are directed superiorly toward the muscles of the cheek and masseter muscle. A prominent buccal branch may be seen connecting this system to the internal maxillary artery superiorly (Fig. 17-1J). Identification of the buccal artery can be assisted sometimes by identifying how it crosses deep to the transverse facial artery without intersecting with it at the level of the pterygoid plates. The buccal artery and posterior jugal artery may be the site of origin of lower masseteric branches from the facial artery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree