Fig. 1.1

Bottom of the second column of the Edwin Smith Papyrus. The hieroglyphs in blue circles refer to watery fluid in context with the surface of the brain (Courtesy of The New York Academy of Medicine Library)

Case number six is of utmost interest with respect to CSF. The patient had “a gaping wound in the head with compound comminuted fracture of the skull and rupture of the meningeal membrane” (Breasted 1930). In this case the meninges were described, but moreover, the word brain (marrow of the skull) occurs the first time in any kind of literature. Apart from the anatomical details, the fluid surrounding the brain, by which the author most likely refers to the cerebrospinal fluid, is also described in this case of brain injury. A number of authors therefore refer to the Smith Papyrus as the first occurrence of the CSF in the medical literature (Clarke and O’Malley 1996; Wilkins 1964) (Fig. 1.2a, b).

Fig. 1.2

1.3 The Greek Physicians and Philosophers

After a long period of lack of documents regarding CSF, it was not before the times of the famous philosophers when further milestones in CSF discovery were achieved by physicians and scientists of ancient Greece (Woollam 1957).

With Hippocrates CSF-related topics reappeared in the literature. The Corpus Hippocraticum dating back to the fifth century BC, a work of many different authors, describes the brain as an organ attracting water from the rest of the body as a pathological process.

In contrast to Hippocrates, Aristotle thought that the heart was the centre of intelligence and the task of the brain was to alleviate the temperature that came from the heart (Clarke and O’Malley 1996). In Historia Animalium he wrote of the membranes around the brain as well as the ventricles which can be found in the “great majority of animals” (Thompson 1910).

Herophilus was specifically interested in the anatomy of the nervous system. As a member of the Hippocratic School, he found the brain to be the centre of thoughts and soul, and the latter he placed to the ventricles. He described the fourth ventricle, the most important one to his mind, as well as the meninges, and his name is still associated with the confluence of sinuses, the torcula Herophili. Also, the choroid plexus appears in his scripts for the first time.

Of note however, there is no direct mentioning of the CSF itself in the ancient Greek literature.

1.4 Claudius Galenus (Galen of Pergamon)

Galen (AD 129–216), a physician and philosopher, was an extremely influential figure in that his work was standard knowledge until the sixteenth century when postmedieval medicine developed and got generally accepted.

Galen developed the famous pneuma (spirits) theory. There were three pneumas, the pneuma zoticon (vital spirit), pneuma physicon (natural spirit) and pneuma psychicon (animal spirit).

The pneuma in general enters the body via respiration into the lungs and through the pulmonary veins as well as the portal veins and reaches the blood where it mingles with the pneuma physicon of the body. The exchange between left and right ventricle of the heart transforms it to the pneuma zoticon, and finally it becomes the pneuma psychicon in the rete mirabile – a vascular network of tiny arteries – at the base of the brain. From there on it enters the anterior horns of the cerebral ventricles and spreads to the rest of the ventricular system. The interesting part is that the pneuma moves along the nerves and by that it operates the muscles (Woollam 1957). The rete mirabile tells us that the anatomical studies were done in oxen, because it does not occur in the human cerebral circulation. Dissection of human bodies was an absolute no-go at that time and in fact for a very long period thereafter. This and the compatibility with Christian trinity were reasons why the pneuma theory held up for more than a millennium.

Before the time of a more fact-based approach, the cerebral ventricles were given various functions; mostly the lateral ventricles were assigned to imagination, the third ventricle to cognition and the fourth ventricle to memory (Sudhoff 1914).

Apart from the flow of pneumas, Galen was ascribed to have discovered a “vaporous humor in the ventricles that provided energy to the entire body” (Conly and Ronald 1983), and also Torack referred to Galen discovering the CSF (Torack 1982). Moreover, he thought that the CSF was produced in the choroid plexus of lateral ventricles and from there passed on to the third and fourth ventricles, an idea that was picked up again only much later in history. Apart from a fluidlike substance in the ventricles, he suggested a fluid between the pia and dura mater. The arachnoid was not mentioned in his books.

This status of knowledge held up through the dark medieval times and was only further developed by the next generation of researchers during the renaissance.

1.5 Leonardo Da Vinci, Andreas Vesalius, Costanzo Varolio (Varolius) and Colleagues

Further advance in the discovery of ventricular and CSF functions started in the renaissance when dissection – particularly human dissection – was reintroduced in medical science. This allowed a more fact-based approach to medical research and started a new epoch in science in general. One milestone was a wax cast of the ventricular system by da Vinci which came, however, probably from an ox’s brain as there were signs of the rete mirabile. Da Vinci used these casts for anatomical drawings of the human brain. His findings came to public knowledge only in the nineteenth century (Clark 1935). The first sketches of the ventricles showed a very vague picture of their topographical order which improved clearly after the wax casts were constructed (Fig. 1.3).

Andreas Vesalius became professor of surgery and anatomy in Padova and later taught at Bologna where he performed public dissections at the specifically designed anatomy theatre. He was strongly opposed to Galen’s work and put much effort in rewriting human anatomy which ended in his most famous book De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (Vesalius 1543). Vesalius initiated a paradigm shift from philosophical approaches to anatomy towards fact-based description of the human body. In order to achieve this goal, he relied on dissection and apparently had access to skilled draughtspersons which led to an unprecedented accurate illustration not only of the ventricles but also of the whole central nervous system. He failed, however, to describe the inter-ventricular foramina explicitly but at least gave credit to a “watery humour” which often was found to fill the ventricles. In his illustration the arachnoid granulations as well as the choroid plexus were depicted in great detail (Singer 1952). Varolius, like Vesalius teaching at the University of Padova, further developed the idea of fluid filling the ventricles rather than spirits, and since then, the pneuma theory was finally left for good (Varolius 1573).

An anatomical fact that was not well covered by the above-mentioned anatomists is the existence of the arachnoid as an important border of the CSF space. The name of the membrane was created by Gerardus Blasius one century later (Blaes 1666). Raymond Vieussens and Frederik Ruysch completed the knowledge by describing its entirety shortly thereafter (Ruysch 1737; Vieussens 1685). Around that time, Antonio Pacchioni precisely described the arachnoid granulations, and he still stands for these structures eponymously (Pacchionus 1705).

Fig. 1.3

View of the ventricles by Leonardo da Vinci before (upper panel) and after (lower panel) performing wax casts illustrating how facts influence knowledge. This fact-based approach was reintroduced during the Renaissance (Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014)

1.6 The Next Generation of Neuroanatomists: Monro, Sylvius, Von Luschka and Magendie

It was now time to discover the relationship between the ventricles and the CSF itself. Interestingly, it was Galen who found a physical communication between the lateral and third ventricle which got forgotten for a long time. The first to describe the inter-ventricular foramen in a distinct and accurate way was Alexander Monro secundus, and he also made it clear that there were no other routes of communication between both laterals as well as between the lateral and third ventricles (Monro 1783). Since then these structures are eponymously known as foramina Monro. Monro was a Scottish anatomist at the University of Edinburgh where he succeeded his father Alexander Monro primus. There were of course others who hinted to or gave partial descriptions before mainly referring to the openings, sometimes as anus or vulva (Casserio 1627; Marchetti 1665). A similar precise account of the foramina was provided by Vicq d’Azyr previous to Monro but not published before 1805.

The connection between the third and fourth ventricle, the aqueduct, has been described in full detail for the first time by Franciscus Sylvius after whom also the lateral cerebral sulcus is named (Baker 1909). Sometimes Franciscus is mixed up with Jacobus Sylvius, teacher of Andreas Vesalius, who provided a rather accurate description but misplaced it as a tube between the midbrain and the cerebellar vermis. Galen already placed a channel close to the aqueduct; it is thought however that this corresponded a portion of the subarachnoidal space of the midbrain. Julius Caesar Aranzi (Arantius), professor of anatomy and surgery at the University of Bologna, came closest to the description of the aqueduct before Sylvius. He actually named it aqueduct but still stuck to the belief that it contained the pneuma psychicon.

Finally, the efflux of CSF from the inner to the outer space – the lateral and median apertures – had to be discovered. There is no known description of these orifices in ancient and medieval literature. Maybe there was no momentum to look into this further as there was the general notion that the pneuma was not to leave the fourth ventricle. It is well established that Magendie gave the first account of the median aperture presenting a wax model of the ventricles including the foramen Magendie. As a profound novelty in brain anatomy, this discovery was a matter of debate for quite a while, not least because he was a difficult character described as vain, stubborn and rash by his contemporaries (Enersen 2014). The median foramen got finally accepted by the work of Key and Retzius (Key and Retzius 1876).

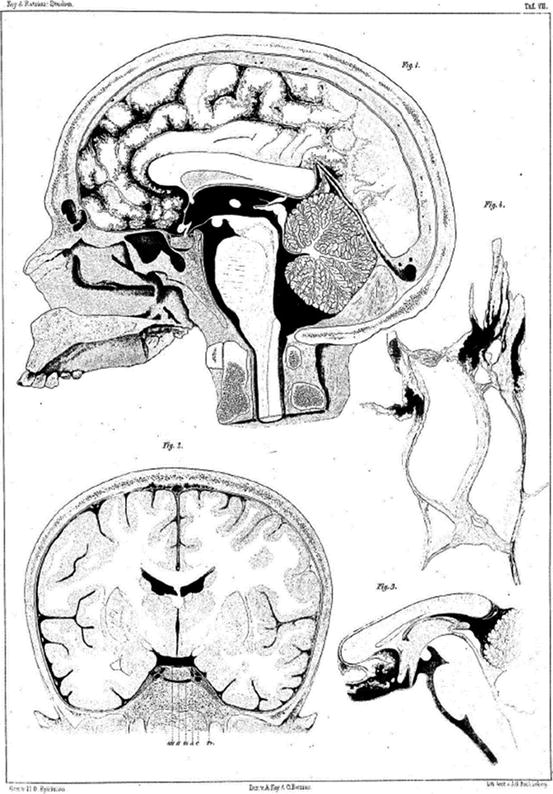

The history of the lateral apertures is less spectacular. They were described by von Luschka (foramina Luschka) (von Luschka 1855) and also by an interesting person named Swedenborg (see below) whose manuscript went unpublished and contained a detailed description of the CSF. The notion that the CSF is produced by the choroid plexus was introduced by Willis and finally established by von Luschka (Willis 1664), whereas its absorption by the arachnoid granulations was acknowledged by the landmark publication of Key and Retzius (Key and Retzius 1876) (Fig. 1.4).