The management of child and adolescent psychiatric emergencies

Gillian C. Forrest

‘Child’ is used throughout this chapter to refer to anyone aged under 18, to avoid the repetition of ‘child or young person’. ‘His’ and ‘her’ are used interchangeably.

Introduction

This chapter provides a practical approach to the management of psychiatric emergencies in children and adolescents. Such emergencies are challenging for a number of reasons. The professional resources available are usually very limited, and there is often confusion or even disagreement between professionals over what constitutes a psychiatric, as opposed to a social emergency. The parents or carers play a key role in the situation and need to be engaged and involved appropriately in the assessment and management; and issues of confidentiality and consent need to be taken into account. In addition, the psychiatrist may find himself or herself working in a variety of settings—the child’s home, a hospital emergency department (A and E), a police station, a children’s home, or residential school—where the facilities for assessing an angry, disturbed, or upset child may be far from ideal.

Most emergencies occurring in community settings involve externalizing behaviours: aggression, violence; deliberate self-harm, or threats of harm to self or others; or extreme emotional outbursts.(1,2) Some will involve bizarre behaviour which could be an indication of serious mental illness or intoxication by drugs or alcohol, or a combination of both. The emergency situation often arises in the context of acute family conflict or distress.

Frequently other agencies are involved before the psychiatrist is called in (for example, emergency room staff, social workers, or the police). The on-call psychiatrist needs to be familiar with or able to obtain immediate advice about his or her local child and adolescent psychiatric services, the local child protection and child care procedures, and with the relevant mental health and child care legislation.

Vignette 1:

A 12-year-old boy is in the police station, after attacking a neighbour and smashing a window. He punched a police officer when they tried to pacify him. He has refused to talk to the police, and is sweating and dishevelled, pacing up and down and muttering to himself. The police think he is psychotic. The neighbour is in the waiting room; his father has been called back from work.

After obtaining the history of the incident from the neighbour and the police, the psychiatrist interviewed the father. The boy had been diagnosed with an autistic spectrum disorder when he was 5. He was easily upset by any change of routine. His mother had gone away for a few days, leaving him in the care of a neighbour while his father was at work. This aggressive outburst was precipitated by the neighbour refusing to let him watch his favourite video. The boy calmed down with his father and a mental state assessment confirmed autistic features but no psychotic symptoms. The psychiatrist persuaded the neighbour and the police to drop charges and the boy was allowed to return home. The family were offered an out-patient appointment but declined this, and arrangements were made for his General Practitioner (GP) to review the situation in a few days’ time.

Vignette 2:

A 15-year-old girl has locked herself in the bathroom at home with a carving knife and is threatening to cut her wrists. Her parents have been unable to persuade her to come out and are now distraught. The GP was called but she refuses to speak to him.†

When the psychiatrist arrived, he asked the family to withdraw so that he could talk to the girl through the bathroom door. She was very upset and described how she had been dumped by her boyfriend earlier that day, had had a row with her step-mother about a large phone bill, and now felt that she didn’t want to live any more. The psychiatrist persuaded her to come out to talk things over with her parents. There was no evidence of a depressive disorder and after the psychiatrist helped the girl share her distress about her boyfriend with her

parents, she calmed down. There was a history of one previous attempt at self-harm, also connected with peer relationship difficulties, and the psychiatrist felt that there were some underpinning issues around family communication. He offered the family an out-patient appointment to explore these further.

parents, she calmed down. There was a history of one previous attempt at self-harm, also connected with peer relationship difficulties, and the psychiatrist felt that there were some underpinning issues around family communication. He offered the family an out-patient appointment to explore these further.

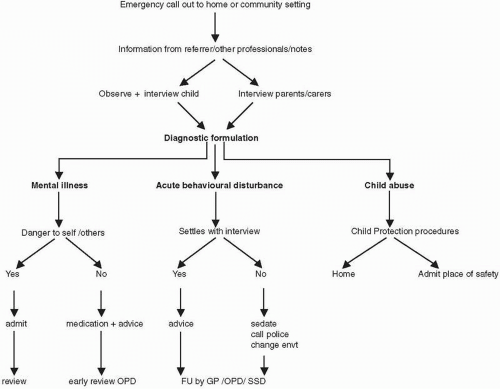

In the emergency situation, the role of the psychiatrist is to:

assess the disturbed behaviour

make a diagnostic formulation which distinguishes behaviour associated with mental illness from that which is a reaction to an upsetting event or situation

produce a care plan to manage the situation safely and effectively in the short-term.

A step-by-step approach to the management of child and adolescent emergencies is described here. The management of deliberate self-harm is dealt with in Chapter 9.2.10.

Step 1. Gathering information

Before attempting to assess the child and his or her family, it is very important to gather as much background information as possible about the incident or behaviour from any professionals who have been directly involved. They may be able to give an accurate description of the child’s behaviour and any incident which preceded it; or useful background information about the family. Take time to read any notes that are available; and talk to those involved (GP, police, paediatric staff, A and E staff, etc.).

Step 2. Interview with the child/young person

Although this is described first, parents may expect to be seen before the child, or it may be preferable to talk to them first to gather background information (see Step 3).

A disturbed or upset child in this situation will be wary of any stranger, and the more out of control they are, emotionally and behaviourally, the more likely they are to be uncooperative initially. The psychiatrist needs to calmly establish that they have come to try and help the child, that they are non-judgemental and that they can be trusted. She should always ask to see the child alone, to establish a confidential relationship, and to be able to assess the child without the influence of parents.

Honest and open communication is essential, especially if there is any possibility of child protection issues. Often the child is terrified

that they are going to be forcibly taken away from their home or family (a desperate and angry parent will often threaten this), and this fear may need to be addressed before the assessment can begin.

that they are going to be forcibly taken away from their home or family (a desperate and angry parent will often threaten this), and this fear may need to be addressed before the assessment can begin.

A useful approach is to say to the child: ‘I’m Dr ….. I’m a psychiatrist who sees children and young people with all sorts of worries and troubles. I’ve come to see you now, to try and understand what this is all about, and see if I can find a way to help’.

If the child refuses to talk at this stage, they may be angry, mistrustful, or psychotically withdrawn. Patience is required to see if this can be overcome by convincing the child that you have come to listen to them and not to ‘take them away’. Reflecting back to the child how you perceive their emotional state may also help. For example, the psychiatrist might say: ‘You are obviously very upset and angry. I wonder what it is that’s made you feel this way’. Sometimes children will choose to communicate by writing notes or drawing, rather than by using speech, and if the child is mute, the psychiatrist should try offering paper and pencil.

If the child remains violent and out of control and the behaviour is being reinforced by attention and anxiety, it will be necessary to ask everyone to withdraw for a while to give the child the chance to calm down on their own. If this still does not help to calm the situation, the psychiatrist will need to set some limits, which could include calling the police to regain control of the behaviour. Medication should only be considered as a last resort when all other strategies to deescalate the situation and calm the child have failed (see Step 5: Management of emergencies in community settings section).

When the child starts to be able to communicate with the psychiatrist, they can then be encouraged to give their account of what happened to precipitate the behaviour. As this is explored, it will be possible to assess the child’s mental state (see Chapter 9.1.3) and to form an impression about whether this is mental illness, or whether the disturbed behaviour is the result of emotional turmoil secondary to relationship problems, family conflict, or other psychosocial issues. Further information from the parents or carers will be needed to clarify this.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree