The NeurAxis Chart

Putting It All Together

Putting It All Together

The rare conditions in medicine are seen infrequently, and the common ones are seen often. For instance, carpal tunnel syndrome is much more common than thoracic outlet syndrome. This rule of commonality applies to both individual conditions and expected patterns of symptoms. When several different symptoms or problems begin at the same time, we are usually correct in assuming they are related to the same condition. The nervous system is also fairly predictable in its behavior based on the level of injury. Each level of the nervous system accounts for a certain amount of neurologic function, so a problem at each particular level presents with its own characteristic set of symptoms and exam findings (signs). The nervous system is diverse but behaves consistently by level, and it is the predicted patterns that will most often and most easily lead you to the correct diagnosis.

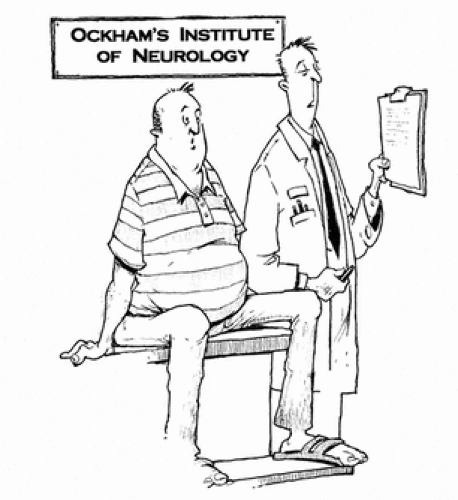

“Pluralitas non est ponenda sine necessitas.”

This latin maxim translates to “Plurality should not be posited without necessity.” William of Ockham (1285-1349) was a controversial 14th-century philosopher often credited with the supposition, “Things should not be multiplied unnecessarily,” although many

experts take exception and argue that this is not exactly how he originally stated what is now called the law of parsimony or “Ockham’s Razor” (sometimes spelled Occam’s Razor). Regardless of origin or intent, the general rule that the simplest explanation tends to be the best (or most likely) serves us well in clinical neurology. For instance, if a person is weak on the entire left side of their body (face, arm, and leg), it is most likely related to a single “lesion.” You know from basic neuroanatomy that this problem would likely be located in the right cerebral hemisphere. Even Ockham himself (with limited knowledge of neuroanatomy) would agree that this pattern could not realistically be attributed to an abnormality of every nerve or root on the left side of the body (without any on the right being affected). Similarly, it is your basic understanding of neuroanatomy that will allow you to postulate which area of the nervous system is most likely affected given the patient’s presenting signs and symptoms. Remember to KEEP IT SIMPLE! Assume from the start that the simplest explanation is the most likely (i.e., The law of parsimony or Ockham’s Razor).

experts take exception and argue that this is not exactly how he originally stated what is now called the law of parsimony or “Ockham’s Razor” (sometimes spelled Occam’s Razor). Regardless of origin or intent, the general rule that the simplest explanation tends to be the best (or most likely) serves us well in clinical neurology. For instance, if a person is weak on the entire left side of their body (face, arm, and leg), it is most likely related to a single “lesion.” You know from basic neuroanatomy that this problem would likely be located in the right cerebral hemisphere. Even Ockham himself (with limited knowledge of neuroanatomy) would agree that this pattern could not realistically be attributed to an abnormality of every nerve or root on the left side of the body (without any on the right being affected). Similarly, it is your basic understanding of neuroanatomy that will allow you to postulate which area of the nervous system is most likely affected given the patient’s presenting signs and symptoms. Remember to KEEP IT SIMPLE! Assume from the start that the simplest explanation is the most likely (i.e., The law of parsimony or Ockham’s Razor).

“It sounds like there may be as many as eight different problems that all started at the same time.” |

If after proper use of this four-step process the patient’s diagnosis remains elusive, then you may assume the problem is more complex than first hypothesized (e.g., possibly involving several different levels of the NeurAxis). However, you should still rely on the patient’s signs and symptoms to direct you to the next most likely level(s) of the NeurAxis for appropriate testing.

“Where is the lesion?”

Students of neuroanatomy will frequently hear this throughout their studies. The question may sound intimidating, but it doesn’t have to be. Start by assuming that there is a simple explanation for the constellation of findings (remember the law of parsimony?). In clinical neurology, arriving at the correct diagnosis usually depends on first simply “bracketing” the problem to two or three potential levels based on the presenting information. These initial possibilities can then be narrowed down further with more focused questioning, a good neurologic examination, and then laboratory testing if indicated. The column of axis levels (see chart) consists of ten functionally separate areas. A distinct pattern of symptoms and abnormal signs is expected when damage or dysfunction occurs at any particular level. Keeping the chart in mind during the evaluation will help you conceptualize the nervous system as a set of interrelated levels instead of an overwhelming list of unrelated diseases. Because some overlap exists between the levels, your initial impression may include several potential areas of involvement and will quickly evolve as additional information becomes available. Your focused history and examination will extract the necessary additional information, leading you to an accurate final impression. The signs and symptoms listed across the top of the chart are a very good place to start (but, of course, are not exhaustive). They consist mainly of the more discriminating and/or common ones encountered and should provide a sense of direction (guide) when collecting and compiling clinical data. The remainder of this chapter covers salient issues related first to each of the NeurAxis levels, and then to the individual signs and symptoms.

NeurAxis levels

The NeurAxis levels are listed as follows:

Cerebral hemisphere

Brainstem

Cerebellum

Spinal cord

Anterior horn cell

Nerve root

Plexus

Peripheral nerve

Muscle

AXIS LEVELS | Cognitive | Seizure | Language (aphasia) | Dysarthria | Visual Field Loss | Dysconj. Gaze | B/B Incont. | Atrophy | Fasciculations | Upgoing toe | Hyperreflexia | Pain, severe | Sens loss | Weak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hemisphere | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

Brainstem | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

Cerebellum | + | |||||||||||||

Cord | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

AHC | + | + | + | |||||||||||

Root | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

Plexus | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

Nerve | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

+ | + | + | ||||||||||||

Muscle | + | + | + | + |

CEREBRAL HEMISPHERE

Problems in one cerebral hemisphere (left or right) typically cause contralateral weakness and/or sensory change. The face, arm, and leg, or any combination of these, may be affected. The amount of dysfunction seen clinically depends on the size of the lesion and precise location of the area involved. Our understanding of the cortical representation of these areas relies heavily on the work of Dr. Wilder Penfield, a famous Canadian neurosurgeon. In the 1930s, using direct brain stimulation techniques, his group mapped the somatic motor and sensory representation in the cerebral cortex on approximately 400 brain surgery patients under local anesthesia (i.e., while awake). A separate motor and sensory homunculus was then drawn along the surface of each cerebral hemisphere, representing the areas of the body that each portion of the cortex serves. The sensory man and motor homunculus (see figures) are products of this work. Understanding cortical representation can be very useful in diagnosing disorders of the cerebrum such as stroke, and is critically

important when considering neurosurgical procedures for problems such as brain tumor or intractable epilepsy.

important when considering neurosurgical procedures for problems such as brain tumor or intractable epilepsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree