, Jeffrey R. Strawn2 and Ernest V. Pedapati3

(1)

Division of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

(2)

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA

(3)

Division of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry Division of Child Neurology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Anatomy is destiny.

—Sigmund Freud

Modern neuroscience has advanced significantly since Freud ’s initial Project for a Scientific Psychology (Freud 1895), in which he hoped to apply scientific principles to the emerging discipline of psychoanalysis. As such, a sophisticated quest to understand the human mind—over the last 125 years—has led to the discovery of a radically different landscape than that which Freud had envisioned. In this regard, multimodal scientific investigations have openly questioned the validity of Freud’s concepts: “[Modern] science not only fails to support the central tenets of Freudian dream theory but raises serious questions about other strongly held psychodynamic assumptions including the nature of the unconscious mind, infantile sexuality, the tripartite model of the mind, the concept of ego defense, free association and the analysis of the transference as a way of effecting adaptive change” (Hobson et al. 2000). Moreover, recent advances in neuroimaging and neurodevelopmental research have profoundly advanced our understanding of the key areas of “the relational brain,” the substrate for two-person relational psychotherapy. Herein, we will briefly review the historical developments of two-person relational psychotherapy, and in doing so, we will detail the specific advances in developmental psychology. Additionally, we will review the key theorists and researchers whose work and behavioral experiments made possible the neurophysiologic investigations, which have, in turn, given rise to our nascent understanding of the neurophysiology of attachment and intersubjectivity.

Work in affective, social, and cognitive neuroscience and neuropsychology have had a significant impact on psychodynamic psychotherapies. However, we distinguish between psychodynamic psychotherapies and psychoanalysis, because child and adolescent psychoanalysis is by and large guided by a traditional one-person psychology (Chap. 2) and has been reluctant to incorporate neuroscience and developmental psychology into current theory and practice.

7.1 Developmental Psychology: A Foundation for the Neurofunctional and Neurostructural Understanding of Two-Person Relational Psychotherapy

Developmental research, and in particular studies with infants, demonstrates that what is stored or represented in the form of memory seems not to involve words or images but rather experiences. Sander (1985) demonstrated that as early as 8 days old, an infant can store a mental representation of the experience of a feeding sequence that when disrupted (e.g., by a mother being asked to wear a ski mask during feeding) generates distress in the infant that is strong enough to suspend his or her feeding behaviors. Thus, memories of experiences are considered precursors to early forms of implicit relational knowing, a representation of how to be with another person that is not language based.

The implicit domain is richer, more complex, and larger in terms of knowing about human behavior than explicit knowledge at all ages, not just in infancy. Thus, implicit relational knowing is based in affect and action rather than in word and symbol (i.e., preverbal) (Lyons-Ruth et al. 1998). This is to say, an infant knows that feeding is a pleasurable experience when seeing and feeling attuned by his or her emotionally available mother and disruptive when the feeding is not accompanied by the mother’s affective attunement . This process is also nonconscious and nonconflicted, meaning it does need to be repressed, as was traditionally believed (Lyons-Ruth 1999). Moreover, this includes not only the desire and idea to act but also the action, the object of the action, and the goal. In an experiment, a preverbal infant observes a research assistant trying to drop an object into a bowl, but who fails by dropping the object in front of and then behind the bowl. Although the infant never sees the object dropped into the bowl, “with the invitation to imitate what he saw, he immediately drops the object directly into the bowl and seems contented with himself. The infant grasped the intention of the experimenter even though he never saw it successfully realized. He gives priority to the intention he has inferred over an action he has seen” (Meltzoff 1995; Meltzoff and Gopnik 1993). In another experiment, an infant watches an experimenter try to pull the spheres off the ends of a dumbbell-like object but fail. Later when the infant is given the object, he immediately pulls the spheres off and seems to feel good about what he has done. The control condition consists of a robot that, like the experimenter, tries to pull the ball-like ends off but also fails. However, when infants are given the dumbbell-like object after they watched the robot fail, they do not try to pull the ends off. These infants have implicitly understood that robots do not have intentions (Meltzoff 1995). Decety and Chaminade (2003) showed that an infant who would imitate a mother putting a doll to bed would not imitate her putting a toy car to bed.

7.2 Core Concepts of Development

The core concepts of development, as outlined by the National Research Council, Institute of Medicine, in the book From Neurons to Neighborhoods (2000), provide a clear and coherent road map of the developmental path of complex interactions between the infant’s innate attributes (i.e., nature) and the influence of family and the environment (i.e., nurture ) in the context of social and cultural factors. Moreover, the dynamic complexities of the relationship between “nature” and “nurture” suggest that the concepts are best understood not as “nature versus nurture, but rather nature through nurture” (Institute of Medicine 2000). Herein, we will review each concept with regard to two-person relational psychotherapy in children and adolescents.

Human development is shaped by a dynamic and continuous interaction between biology and experience

This concept is essential in understanding the complex dynamic world from which our young patients come. Relational theory, which encompasses two-person relational psychology, attends to the variability of neurobiology (e.g., innate temperament , mirror and echo neuron systems, attachment patterns, the family system, and the cultural aspects of both patient and psychotherapist). It is the amalgam of these factors that ultimately influences the interaction between the patient and psychotherapist and that allows for the cocreation of a unique intersubjective experience. Moreover, two-person relational psychotherapy can influence (through neuroplasticity -dependent mechanisms) the acquisition of a better model of adaptation to the relational world, and this process almost certainly has neurophysiologic foundations. This process in which experience facilitates neurostructural and neurofunctional changes has been eloquently demonstrated in several recent preclinical studies, which collectively suggest that the relationship between early stress and adversity, as well as poor-quality interpersonal experiences (e.g., being raised in an international orphanage), is associated with deficits of functional connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex . Additionally, in lower animals, early-life adversity is associated with changes in neuronal architecture in regions that—in humans—likely subserve the encoding of relational experiences (e.g., hippocampal neurons) (McLaughlin et al. 2007) and in cortical areas responsible for the processing of interactions (e.g., cortical pyramidal neurons) (Vyas et al. 2002). Additionally, there is evidence, again in lower animals, that chronic, early adversity may drastically alter the morphology of the neurons within the amygdala, including increased dendritic arborization and the lengthening of dendrites (Fig. 7.1) (Vyas et al. 2006).

Fig. 7.1

Chronic environmental stress (blue) results in increased arborization, increased dendritic spine density, and elongation of dendrites in the basolateral amygdala compared to dendrites from animals who have not experienced environmental adversity (red)

Culture influences every aspect of human development

As we have reviewed elsewhere (Delgado and Strawn 2014), culture —the constellation of languages, social customs , traditions, beliefs, and values shared by a group of people linked by family, race, ethnicity , region, or culture of origin—profoundly influence human development. Additionally, an individual’s culture influences what is considered the norm for loving and stable relationships. This norm will guide prenatal care, birth delivery systems accessed, feeding, sleeping, and parenting practices. Regarding concepts that are germane to two-person relational psychotherapy (e.g., “meaning making” and “implicit relational knowing”), it is clear that culture contributes to the shaping and development of these processes, as well as to the underlying neurofunctional and neurostructural bases of these processes.

Recent functional neuroimaging studies of Asians compared to Caucasian Americans have demonstrated interesting findings in this regard. When individuals from cultures that “habitually attend to the needs, perspectives, and internal experiences of others compared to the self” viewed images of others in emotional pain, increased activation of the anterior cingulate cortex and insula is observed in the Asian subjects relative to the Caucasian American subjects. This suggests that culturally bound “attunement to the subjective experience of others” may be associated with neurofunctional differences across cultures (Cheon et al. 2013). Additionally, the degree of dependency in cultures affects the processing of anger, “an emotion that implies the disruption of harmony.” In this regard, during a task of empathic processing, healthy Chinese individuals, who in this study are self-described as more interdependent than German individuals, have increased activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex , while the Germans exhibited increased activation of the inferior and superior temporal gyrus (de Greck et al. 2012). Moreover, the activation in the inferior and superior temporal gyrus correlated with the degree of independence in the sample, suggesting that increased culturally related tolerance for anger is associated with activity in the inferior and superior temporal gyrus and insula (de Greck et al. 2012). Thus, while individual differences in empathy and experience may direct these neurofunctional differences and the process is likely multidimensional with genetic and state-dependent modulation, it is clear that culture is the ever-present factor that influences the ways we communicate with patients, inhibits or enhances our understanding of their illnesses, and provides the context that explains their reactions to the event (Delgado and Strawn 2014).

The growth of self-regulation is a cornerstone of early childhood development that cuts across all domains of behavior

Children have the complex task of implicitly and nonconsciously learning to manage emotions in the context of interpersonal interactions, in addition to learning to regulate their internal physiological states. This complex task is beautifully captured by Winnicott in his famous aphorism, “There is no such thing as a baby,” meaning that without a mother, an infant cannot exist, and we now recognize that infants have an intrinsic need for interaction with their caregivers. Put differently, Emde (1987) notes that “infants’ emotions are, by their nature, relational.”

Thus, the child with a history of problems in self-regulation due to developmental or cognitive delays (e.g., autism , ADHD , learning disabilities) may benefit the most from a more structured approach or a more behaviorally oriented approach (e.g., parent–child interaction training [PCIT], behavior management) or, in the case of ADHD, from pharmacotherapy. Nonetheless, we are not implying that psychodynamic psychotherapy is not helpful to some children with self-regulation problems; we are saying that a careful assessment of these aspects will allow for a detailed identification of those that will not benefit from psychodynamic psychotherapy. Additionally, it is important to note that the capacity for self-regulation may be significantly influenced by trauma (Schore 2002). In this regard, children and adolescents with histories of maltreatment exhibit deficits in a myriad of neuropsychological domains, including attention and abstract reasoning/executive function, which likely subserve the capacity for self-regulation (Beers and DeBellis 2002). Moreover, there is also evidence to suggest that the neural circuitry of self-regulation is altered in children and adolescents who have experienced significant trauma. For example, Herringa and colleagues (2013) observed lower resting-state functional connectivity between the hippocampus and subgenual cingulate and reduced resting-state functional connectivity between the amygdala and cingulate cortex in maltreated youth relative to healthy comparison subjects. Additionally, in this sample, resting-state connectivity for these structures mediated the association of maltreatment earlier in life and the presence of internalizing symptoms in adolescence, suggesting that early maltreatment “may alter the regulatory capacity of the brain’s fear circuit, leading to increased internalizing symptoms by late adolescence” (Herringa et al. 2013).

Children are active participants in their own development, reflecting the intrinsic human drive to explore and master one’s environment

There is an innate developmental motivation on the part of a child to master his or her environment and to learn “getting along” with others. Moreover, early positive experiences with caregivers have a profound role in the developmental process in that it promotes affect regulation and the neurophysiological changes entailed. Herein, a child is an active participant in their development, seeking to elicit the affectively attuned responses needed from their caregivers for a successful process.

Human relationships and the effects of relationships on relationships, are the building blocks of healthy development

Attachment theory (see Chaps. 3 and 8) provides a longitudinal view of the way in which a child establishes early dyadic relationships with his or her parents or caregivers. In turn, these relationships determine the quality of emotional relationships that the child will have with others throughout his or her life span. As such, the internal working models of relationships and the goodness of fit both serve as foundations for and ultimately facilitate interpersonal relationships. It is recognized that developmental or behavioral disturbances in infants and toddlers may be a product of disturbances in the infant–caregiver dyad (Bowlby 1999; Sameroff and Emde 1989). In this regard, this discordance appears to have a neurofunctional basis. As such, a recent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI ) study involving mother–infant dyads observed that mothers who were more sensitive to their infants had increased activation of the right prefrontal cortex , including the right inferior frontal gyri, in response to their infants’ cry, compared to those mothers who were less sensitive to their infants (Musser et al. 2012). Additionally, in this study, mothers who exhibited more intrusive responses to their infants had increased activation in the left anterior insula and temporal pole, whereas mothers who had more harmonious interactions with their infant displayed greater activation in the left hippocampal regions (Musser et al. 2012).

The broad range of individual differences among young children often makes it difficult to distinguish normal variations and maturational delays from transient disorders and persistent impairments

Differences in cognitive and affective ability affect one’s ability to achieve developmental competency or, in other words, to participate in rewarding experiences with others. In this regard, neuroimaging studies suggest structural and functional brain abnormalities associated with the presence of cognitive and linguistic communication disorders that underlie these differences in cognitive and affective ability (Delgado et al. 2011; Frodl and Skokauskasm 2012; Lai 2013; Webster et al. 2008). Specifically, regarding learning disorders, 10 % of the general population may have learning weaknesses, and among this group, many have formal learning disabilities (Altarac and Saroha 2007; Cooper et al. 2007). Considering these statistics, there is a selective group of children and adolescents that have persistent impairments that make it difficult to assess maturational norms. Further, there is a group of children with physical disabilities, including individuals with visual impairments, hearing impairments, speech disorders, etc., who may experience maturational delays. However, it is critical to recognize that within such a group, there will be significant variability in apparent cognitive and affective ability, and it is of great importance to carefully characterize any deficits in the context of these sensory limitations.

The development of children unfolds along individual pathways whose trajectories are characterized by continuities and discontinuities as well as by a series of significant transitions

Development in children and adolescents occurs as a series of transitions that are typically punctuated by physiological and physical changes that parallel adaptive psychological advances (Emde and Harmon 1984). A range of putative mechanisms likely mediate these developmental processes, as well as heterotypic continuity and psychopathologic progression. These mechanisms include gene x environment interactions , “‘kindling’ effects, environmental influences, coping mechanisms and cognitive processing of experiences” (Rutter et al. 2006). Moreover, when developmental transitions are due to or coincide with a serious illness or traumatic event, significant physiological and physical changes that end in psychological discontinuities with maladaptive mechanisms may ensue.

An example frequently seen by mental health professionals that captures the continuities and discontinuities of children is toilet training . This process can occur along several possible pathways. For some, it may occur when developmentally expected (between 24 and 36 months) and without major difficulties, while for others, parental anxieties and wishes to have toilet training occur sooner or more quickly may result in discontinuity with varying psychological sequelae. We clearly have come a long way from early psychoanalytic thought in which problems with toilet training were considered to be due to a fixation or regression of anal-level intrapsychic conflicts.

Human development is shaped by the ongoing interplay among sources of vulnerability and sources of resilience

The way in which a child adapts to physical and emotional life challenges depends on the innate factors that activate specific gene expression patterns, resulting in the production of protective and regulatory factors. However, some children may be more vulnerable than others and may be less affected by family or environmental adversity. The susceptibility to stressful or traumatic events for a particular child continues to be difficult to determine, and it will be critical for future work to explore these factors, particularly in “dandelion children” (i.e., those youth who are psychologically resilient and able to survive under adverse circumstances) (Boyce and Ellis 2005; Dick et al. 2011). Recently, several studies of the genetic basis of resilience have focused on functional polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter promoter region. Caspi and colleagues first described this mechanism in a longitudinally followed cohort study in which this particular functional polymorphism moderated the effect of adverse events on the subsequent development of depression. In this regard, individuals who had one or two copies of the short alleles exhibited increased depressive symptoms compared to individuals who were homozygous for the long allele when they had experienced significant life adversity (Fig. 7.2), “thus providing evidence of a gene-by-environment interaction, in which an individual’s response to environmental insults is moderated by his or her genetic makeup” (Caspi et al. 2003).

Fig. 7.2

Serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism predicts likelihood of developing depression as a function of stressful life experiences. The red line represents individuals who contain two short alleles (s/s), whereas the green line represents individuals who contain one short allele and one lone allele (s/l) and the blue line represents those individuals who are homozygous for the long allele (l/l) (Adapted from Caspi et al. (2003))

The timing of early experiences can matter but, more often than not, the developing child remains vulnerable to risks and open to protective influences throughout the early years of life and into adulthood

The recognition of a children’s neurodevelopmental plasticity in response to environmental changes reflects “the capacity of the brain to reorganize its structure or function, generally in response to a specific event or perturbation” (Institute of Medicine 2000), and “varies inversely with maturation,” affirming the need for early interventions in order to achieve the best outcomes. Accordingly, the two-person relational psychotherapist facilitates brain neuroplasticity through here-and-now, intersubjectivity-based experiences, which promote the development and strengthening of specific brain circuits that are increasingly capable of processing mutual understandings when relating to others.

The course of development can be altered in early childhood by effective interventions that change the balance between risk and protection, thereby shifting the odds in favor of more adaptive outcomes

The most effective two-person relational interventions occur early in the course of development and are tailored to the physical and emotional needs of each child or adolescent and their family. The interventions should be tailored to help the child or adolescent resume their developmental tracjectory and should also facilitate the family unit’s return to a homeostatic state, rather than relying on a theoretical formulation that may limit the breadth of interventions needed.

7.3 The Neurobiology of Two-Person Relational Psychotherapy

To understand the neurobiology of two-person relational psychotherapy and of the developmental concepts described in this text, we must understand a number of key concepts in neuroscience. In the sections that follow, we will explore the neurophysiology of these key concepts: (1) neuroplasticity , (2) the mirror neuron system , (3) the default mode network , (4) social referencing and affective attunement , (5) temperament , and (6) reflective functioning . For each of these processes, the relevant brain structures and connectivity will be described.

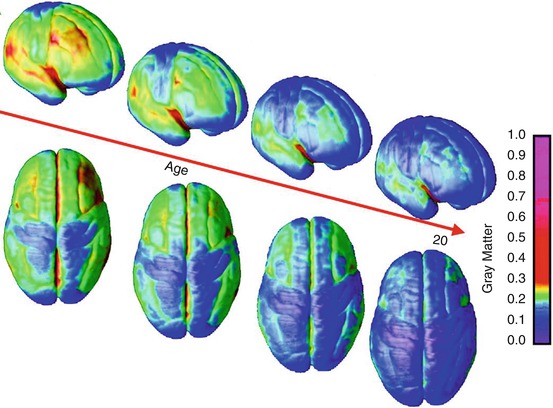

Neurodevelopment: A Broad Overview

The development of the human nervous system is dependent on a myriad of genetic and environmental factors. Additionally, there is significant remodeling of the nervous system throughout development as an effect of experience, exposure to events, learning, and through various epigenetic processes. Importantly however, while neural connectivity changes throughout life, it is during infancy, the early school age years, and then puberty that the greatest rate of change occurs. It is also during these periods that there are significant regional changes in gray matter volumes (Fig. 7.3). Many of these neurodevelopmental processes rely on neuroplasticity-related phenomena. In short, neuroplasticity refers to the changing of neural networks through both “pruning ” and also through the strengthening of synaptic connections. Thus, as the brain processes sensory information, frequently used synapses are strengthened while unused synapses weaken and eventually cease to exist. Certainly, neuroplasticity has critical importance in two-person relational psychotherapy as summarized by Buirski and Haglund (2009): “Successful treatment leads to the formation of new organizations of experience, new ways of understanding oneself, and new expectancies based on these new understandings…. What happens to the archaically formed ones? They neither disappear, are forgotten, nor are completely replaced by the newly formed ones. Rather, they persist in weakened form within the organization of the personality.” They conclude by stating that when a person is under “duress, old maladaptive organizing principles can reemerge, reviving past negative, self-defeating experiences.” In essence, two-person relational psychodynamic psychotherapy aims to provide a corrective emotional experience (Alexander et al. 1946).