The Neurologic Examination

Tips and Techniques to Help Improve Your Yield

Tips and Techniques to Help Improve Your Yield

The neurologic exam can be fairly simple to perform and interpret if you approach it systematically as you do the history. Keep the NeurAxis in mind as you assess the patient, learn the correct method for performing each portion of the exam, and apply appropriate terminology to help avoid confusion.

“The neurologic exam was stone-cold normal.”

This is what the neurologist often hears near just before detecting several subtle but significant abnormalities on his or her neurologic exam. A brief screening exam can be useful for triaging patients but may not always reveal subtle abnormalities. These incomplete exams are sometimes reported as “stone-cold normal.” Remember that neurologic patients often exhibit subtle abnormalities that are exposed only when you focus on a particular region or “push the edge of the envelope” with regard to testing nervous system function. One of the most sensitive, albeit impractical, methods of assessing the nervous system would be to observe patients in their own environment. Watching them ride a bike, prepare a meal, balance a checkbook, or plan a vacation would all be very telling. Because this is rarely possible, simple suggestions are offered throughout this chapter to help you improve your yield in identifying and recording abnormalities on the mental status, cranial nerve, motor, and sensory portions of your exam.

“Neurologic exam was grossly normal.”

The author of this particular statement knows what he found on the examination. Unfortunately, nobody else can really be certain. Almost as important as the examination is the record of it. Accurate documentation allows others to know what was done and what was found. Many who record a “grossly normal exam” will admit that they didn’t actually test strength or sensation, but the patient “seemed normal” when observed during a brief encounter (sometimes from the doorway).

If muscle strength is entirely normal, then briefly list the muscles tested and record muscle power in these as normal. If your exam is incomplete, avoid the urge to label strength “pretty good throughout” or “grossly normal.” Briefly note which tests were performed (e.g., gait, station, strength) and complete the exam later when time allows. Using more specific, less ambiguous terms is also helpful, so avoid generalizations and eponyms when possible. Results written

descriptively are useful for the examiner and can even be reinterpreted later by others, if necessary.

descriptively are useful for the examiner and can even be reinterpreted later by others, if necessary.

|

Member: secret service

Some residents refer to dermatologists, neurologists, and ophthalmologists as members of the “secret service” because few seem to inherently understand their jargon. Unfortunately, semantic confusion in medicine can be a real problem, occasionally leading to time-consuming delays in management. A good way to avoid this is to use descriptive language in lieu of confusing terms and misunderstood eponyms. As one of our residents added, “If eponyms impress the friends you hang out with, then maybe you should get out more.” Reporting what you found in a more straightforward manner helps streamline care and avoid unnecessary delays in management.

“He had a left-sided stroke.”

If you have ever written something similar, it was obvious to you at the time what you meant. However, “left-sided stroke” may refer to left-sided weakness (due to a right hemisphere stroke) or right-sided weakness (due to a left hemisphere stroke). In my experience, the student or resident usually means left-sided somatic weakness. If you have ever been called to reevaluate a stroke patient quickly (especially late at night when the admitting team is not present), you know the value of a precise and descriptive diagnosis. Try this next time: “Mr. Jones suffered from a right cerebral hemisphere infarct and exhibits left-sided face, arm, and leg weakness.” You might even shorten it to the following when you are summarizing the patient’s condition: “Right hemisphere infarct with left body weakness.”

“She was stuporous yesterday but obtunded this morning.”

Is it clear to you whether this patient’s condition has improved or worsened over the past 24 hours? Terms like these rarely provide useful information beyond the obvious implication that the patient is not entirely normal. A simple description of the patient’s condition would be much more helpful in day-to-day care and for those who may follow the examiner. The best description usually originates with a mental picture of how the patient appears to you at the time. For

example, see if this description helps you more than either of the previous terms: “Ms. Doe is currently supine, intubated, and breathing spontaneously above the ventilator setting of 12 breaths per minute. She opens her eyes to vigorous shaking but not to verbal stimulation/command.” Make a habit of using specific terms that add clarity, not those that tend to confuse others and obscure the clinical picture.

example, see if this description helps you more than either of the previous terms: “Ms. Doe is currently supine, intubated, and breathing spontaneously above the ventilator setting of 12 breaths per minute. She opens her eyes to vigorous shaking but not to verbal stimulation/command.” Make a habit of using specific terms that add clarity, not those that tend to confuse others and obscure the clinical picture.

“Mental status seemed normal.”

The mental status exam consists of more than asking a person if they can recall their name, current date, and three objects. There are more questions that need to be asked and different ways to perform the exam, depending on how the information is to be used. The mental status exam and “Mini Mental State” exam are not synonymous. The Mini Mental State exam is a simple standardized cognitive screening test that can be used as a research tool and in the clinic. However, it is not a particularly sensitive test of cognitive function. Many intelligent and highly educated patients may perform very well on this brief exam, even when suffering from early dementia. There are other similar brief tests of cognitive function with good interrater reliability that have also been copyrighted (e.g., the Short Test of Mental Status). Remember, family members may notice problems at home or in the work environment long before these types of tests are significantly abnormal, especially in highly educated patients.

For a more comprehensive picture of higher-level cognitive function, take the time to carefully interview the patient’s family and/or friends. Then discuss current events, hobbies, and other interests with the patient him- or herself. Open-ended questions such as “Who runs the country?” or “What do you like to do?” allow for individuality of answers. Narrow or overgeneralized responses are common in early dementia. Asking “What’s going on in the world right now?” will lead to responses such as “chaos,” “wars everywhere,” or “lots of trouble.” With follow-up questioning, these patients are often unable to provide a description, explanation, or any significant/accurate details. “The president” may be all this patient offers when asked “Who runs the country?” Be careful not to give credit for a correct answer just because you agree with their opinion they jokingly respond, “Oh, that rascal, you know who it is….” Those functioning at a normal level will usually provide a proper name and may even spontaneously provide details related to the inner workings of a representative republic. If your patient is a sports fan, then discuss his or her favorite team. If your

patient is a gardener, then talk with him or her about plants. Patients with dementia will provide fewer details and shorter lists (e.g., types of flowers or vegetables one might grow, different animals found on a farm, or teams in a league). These and similar questions will provide much more information than the standard dementia profile and are less awkward than asking “Do you know where you are?” or “Can you tell me your full name?”

patient is a gardener, then talk with him or her about plants. Patients with dementia will provide fewer details and shorter lists (e.g., types of flowers or vegetables one might grow, different animals found on a farm, or teams in a league). These and similar questions will provide much more information than the standard dementia profile and are less awkward than asking “Do you know where you are?” or “Can you tell me your full name?”

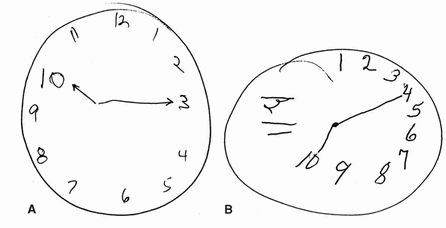

Clock drawing test

If you are interested in a screening test and not a full mental status evaluation, a very good test that assesses executive function quickly is the clock drawing test. It takes only a minute or two to perform, is easy to interpret, and crosses cultural and educational boundaries. Just ask the patient to draw the face of a clock with the numbers on it. Then ask them to show a specific time on the clock, such as “twenty ’til eleven” or “ten fifteen.” Each number should be correctly located and evenly spaced. There should be two hands of different lengths that point at or near the correct numbers for the time indicated.

These two patients (see clocks) were asked to indicate “ten fifteen” on their clocks. You can see that patients do not need to speak English or have a formal education to draw a simple clock face. Can you easily tell which of these two is abnormal?

These two patients (see clocks) were asked to indicate “ten fifteen” on their clocks. You can see that patients do not need to speak English or have a formal education to draw a simple clock face. Can you easily tell which of these two is abnormal?

|

“I didn’t have a vision card to test acuity.”

Two important tests often omitted from the cranial nerve exam are visual acuity and visual fields. Patients are quick to detect and report complete loss of vision or change in acuity but may not even be aware of diminished peripheral vision. Loss of peripheral vision in either or both eyes can occur insidiously if progression is slow. You should check the respective visual fields in each eye by confrontation testing. Visual acuity can be reliably estimated even if you don’t have a formal vision card available. Use a newspaper, magazine, or even your ID tag. Standard newsprint at half an arm’s length requires about 20/40 acuity. Using a magazine or newspaper, start with the headlines or larger print and move to smaller letters or numbers based on the patient’s ability. This information will be useful immediately and will help later, especially if vision changes are reported.

Pupils should be tested with the overhead lights off to allow for full dilation, and for accurate comparison of size and shape between sides. A very useful tool for examining small or minimally reactive pupils is a lighted magnifying glass. These can be purchased for a few dollars at your local drugstore. If you like to use the abbreviation “PERRLA” be sure to actually test for accommodation. You may want to simply describe size, shape, and reactivity instead. Most

students realize quickly that the funduscopic exam is simple but not always easy. Seize the opportunity to practice your funduscopic exam on younger patients while the light is dimmed. This will help you develop the skill necessary to see the fundus in older patients with small pupils or mild cataract.

students realize quickly that the funduscopic exam is simple but not always easy. Seize the opportunity to practice your funduscopic exam on younger patients while the light is dimmed. This will help you develop the skill necessary to see the fundus in older patients with small pupils or mild cataract.

“I didn’t watch them walk.”

Deciding which portions of the exam to perform can be difficult when time is short or the patient’s cooperation is limited. Two of the most useful neurologic tests overall are assessment of walking and talking. If time or other constraints prevent a complete exam, then these two will usually be at the top of your short list. Ironically, both are sometimes omitted in the hospitalized patient. In an effort to avoid “bothering” the person who appears ill or tired, a full mental

status exam and even conversation are bypassed. Likewise, gait analysis can be cumbersome and is, therefore, often omitted when several “lines” are in place (e.g., IV, oxygen, urinary catheter).

status exam and even conversation are bypassed. Likewise, gait analysis can be cumbersome and is, therefore, often omitted when several “lines” are in place (e.g., IV, oxygen, urinary catheter).

There are several reasons that assessment of gait and station, speech, and language are so valuable. If gait appears entirely normal, then balance, lower extremity strength, and coordination are all probably good. Even minor abnormalities can affect the speed of walking, rhythm, or symmetry of movements. A substantial amount of neurologic function is also reflected in a brief verbal exchange. If the examiner is attentive, then speech, language, mentation, and even emotion can all be at least partially assessed. Learn to focus all of your attention on the patient during the interview because other problems such as subtle facial asymmetry, fluctuations in voice, fasciculations, and abnormal limb movements may be transient.

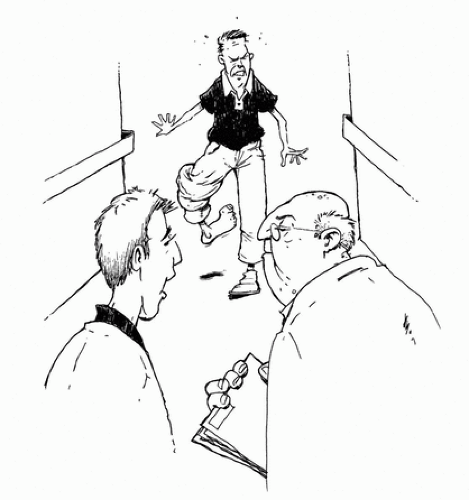

The 30-second neurologic exam

This exercise will help you hone your neurologic skills and streamline your evaluation at the same time. It will also prove to you how much information assessment of walking and talking provides. Before you formally evaluate a clinic patient with any neurologic symptom, formulate a presumptive diagnosis with limited information as follows: Note the chief complaint, and then simply watch the patient walk down the hall into the examination room. Carefully observe the patient’s gate, the way he or she moves, and how he or she interacts with others along the way. At that point, you should have enough information to come up with a relatively short list of potential diagnoses. This brief encounter will provide valuable clues by helping you answer the following questions: Was the patient’s gait smooth and steady with good rhythm and arm swing? Was limping, staggering, or pain evident? Were upper and lower extremity movements symmetric and coordinated? Did the patient sway, stagger, touch the wall for balance, or stop for rest? Was assistance or a walking aid necessary? How did the patient respond to the desk personnel, and was the patient attentive and conversing intelligibly with his or her family? Was the patient’s speech slurred or voice hypophonic? Did the patient appear confused, tired, anxious, or happy? The information you now have will take you a long way toward a likely diagnosis.

For instance, right upper extremity adduction with elbow/wrist flexion and circumduction of the right lower extremity would suggest pyramidal predilection (upper motoneuron) weakness. If combined

with ipsilateral facial weakness or paraphasic language errors, then a left cerebral hemisphere problem could be presumed (possibly cerebral infarction in the elderly patient). If, instead, the patient was limping and/or grimacing with each step, then a more peripheral problem may be suspected (possibly mechanical in nature). You might consider a cardiac, respiratory, or peripheral vascular problem if the patient stopped to rest. Bending forward at the waist along the way to ease leg discomfort would suggest spinal stenosis.

with ipsilateral facial weakness or paraphasic language errors, then a left cerebral hemisphere problem could be presumed (possibly cerebral infarction in the elderly patient). If, instead, the patient was limping and/or grimacing with each step, then a more peripheral problem may be suspected (possibly mechanical in nature). You might consider a cardiac, respiratory, or peripheral vascular problem if the patient stopped to rest. Bending forward at the waist along the way to ease leg discomfort would suggest spinal stenosis.

This simple exercise is valuable for patient care, and encourages use and manipulation of the NeurAxis. Try it along with a fellow student or colleague and compare notes. No wagering, please.