3 The neurological examination

Cranial nerves

CN II (optic nerve)

This requires four separate tests: field, fundi, acuity and pupils.

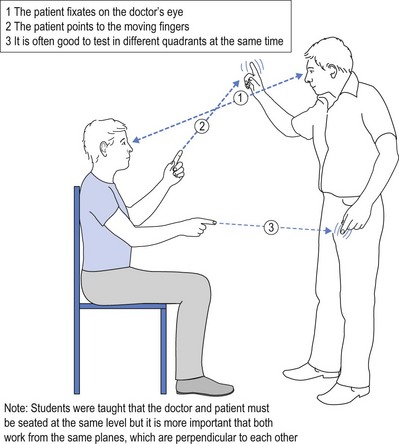

Fields are tested by confrontation, by standing in front of the patient and randomly wiggling fingers in each of the four quadrants of the visual fields (Fig 3.1).

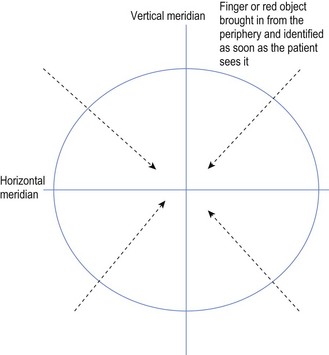

The patient is asked to point at the wiggling fingers, and at times it is worth wiggling fingers in more than one quadrant to encourage the patient to pay extra attention. If this test suggests abnormality, then each eye should be tested individually by covering the other eye. The crude test has the doctor wiggle the finger in each of the four quadrants of the visual field and the patient must identify the wiggling finger. More sophisticated testing has the doctor move the fingers in on the diagonal in each quadrant (see Fig 3.2).

The patient is asked to indicate as soon as the finger is seen, and the doctor compares this to their own perception of the finger to see if there is parity between doctor and patient. Use of a red object, such as a red pin, produces a more precise definition of the field of vision. The patient is asked to nominate when the pin is clearly perceived as red, thereby relying on colour vision, rather than a relatively large moving object. Loss of vision must respect the horizontal and vertical meridians to be anatomically sound (see Fig 3.2).

When the patient is uncooperative and will not point to the moving finger or object, an alternative method for testing visual fields is to use ‘menace’. Menace employs a motion as if the examiner is going to poke the patient in the eye, either with a fist or flattened hand, stopping just short of the point of contact. If the patient has preserved vision within the quadrant being tested, it is almost impossible for the patient to avoid blinking. This is an innate, self-protective reflex evoked by the patient seeing the menacing object, such as a fist, approach. Failure to blink in the face of such menace suggests blindness in the fields being tested. It is not absolute but it is very suggestive.

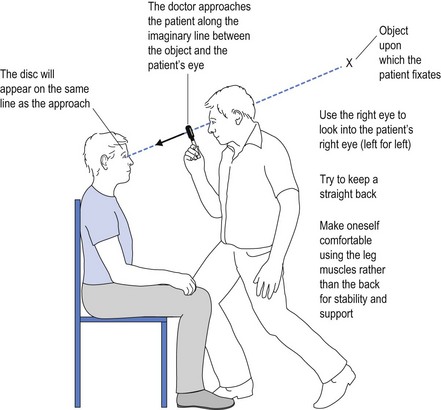

Fundi are tested using an ophthalmoscope. It is important to use the right eye to examine the right eye, to approach the patient from directly in front to avoid the forehead covering the line of vision of the other eye (the one not being examined) and to place the disc (that is, optic nerve) where it is most convenient to view it, rather than looking for it. The way to do this is to ask the patient to look at a convenient object that allows the examiner to approach using that line which follows an imaginary line drawn between the object and the eye (Fig 3.3).

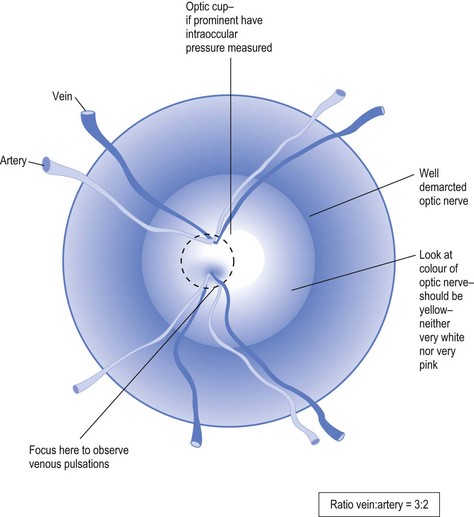

The optic disc contains within it an internal ‘cup’. If this is very obvious it may simply be a variant of normal but it may also herald the first sign of glaucoma and, hence, if noted, should alert the examiner to seek measurement of intraocular pressure from either the optometrist or ophthalmologist.

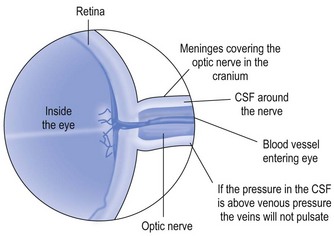

If the disc margins are ‘blurred’, this may reflect any number of normal conditions, such as medullated nerve fibres (fibres with myelin still in place) but it may also reflect papilloedema. Papilloedema is usually accompanied by haemorrhages and an angry looking disc (see Fig 3.6). Perhaps the first sign of papilloedema is a loss of venous pulsations, which can be seen in 90% of normal people. To seek out venous pulsations, the operator must identify the disc and focus upon it. The relative ratio of arteries to veins is 2 : 3, with the veins being the wider and darker vessels. The doctor selects the end of the vein before it disappears into the nerve, and focuses on that end. If venous pulsations are present then the vein will fill and empty while being observed. Alternatively, the vein may change from fatter to thinner in rhythmic fashion while pulsating. The presence of venous pulsations automatically excludes the presence of raised intracranial pressure but, as already stated, up to 10% of the normal population do not demonstrate such pulsations. Thus, absence of venous pulsations need not reflect raised intracranial pressure, while their presence excludes it (see Figs 3.4 and 3.5).

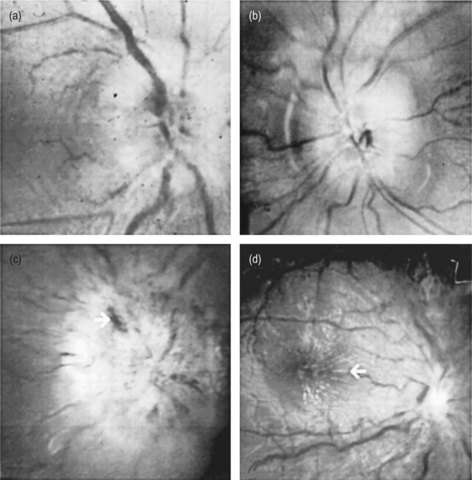

FIGURE 3.6 Papilloedema.

(Kliegman. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18th edn. 2007 Saunders; Figure 591-1 (a) Mild papilloedema. Blurred disc margins and venous congestion. (b) Moderate papilloedema. Disc oedematous and raised. Vessels buried within substance of nerve tissue. (c) Severe papilloedema. Haemorrhages are evident within disc (arrow), and there are microinfarcts (soft exudates) in the nerve fibre layer. (d) Macular star (arrow) with oedema residues distributed within the Henle layer of the macula.)

There are basically only four causes of ptosis:

Shining the light into the right pupil and shielding that light from the left eye should evoke constriction of both pupils. The right eye constricts because of direct response of the light onto the right optic nerve. The left pupil constricts because that message from the right CN II is transmitted consensually to the left pupil via CN III and parasympathetic fibres. Thus blindness in the right eye will prevent the process happening, and damage to the transmission via CN III, assuming functioning right eye, will result in no pupillary response on the left.

Having evoked the response from the right pupil, the shielded light is focused onto the left eye. This should result in a repetition of the above response. If the left eye is blind and does not constrict, then both pupils may dilate as a relaxation of the previous constriction. This does not imply the dilatation is evoked by the left eye, but rather that the left eye cannot perceive the light and does not prevent the dilatation consequent to the earlier constriction. This is known as the ‘swinging lantern sign’.