- Parasomnias are unwanted motor or sensory nocturnal phenomena that are usually categorised by the sleep stage (e.g. non-REM or REM) from which they most commonly arise

- Phenomena such as sudden body jerks at the wake–sleep transition are common as isolated events but can produce more elaborate or complex symptoms that interfere with sleep onset

- Abnormal partial arousals from the deep stages of non-REM sleep reflect the most common type of parasomnia, affecting up to 20% of children at some point in their development

- Sleepwalking, night terrors and confusional arousals from sleep probably reflect different manifestations of the same process (i.e. non-REM sleep parasomnia)

- In adults, non-REM sleep parasomnia activity may lead to antisocial or dangerous nocturnal behaviours that may be ‘goal-directed’ or ‘instinctive’ in the absence of voluntary or conscious control

- There is very little evidence to guide treatment protocols for troublesome parasomnias

- Nightmares and occasional episodes of sleep paralysis reflect the commonest forms of parasomnia occurring from REM sleep

- Prolonged motor activity during REM sleep producing dream enactment is abnormal and may indicate REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD)

- RBD is important to recognise as it may reflect the earliest manifestation of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease

- Several motor phenomena at night disturb the bed partner more than the sleeping subject (e.g. bruxism, nocturnal groaning and fragmentary myoclonus)

Parasomnias are loosely defined as undesirable motor or sensory phenomena arising from sleep itself or the sleep–wake transition. The majority can be explained in terms of an abnormal or inefficient transition from one distinct brain state (i.e. wake, non-REM sleep or REM sleep) to another. Alternatively, elements of one sleep state (e.g. the bizarre or unpleasant visual imagery in REM sleep) can intrude or persist into the wakeful state.

The range of possible experiences and behaviours is enormous, from simple visual images to complex and seemingly purposeful motor activities. Many parasomnias are disturbing both to the subject and bed partner, with fear responses or physical aggression as major components. However, it is not uncommon for subjects to have no subsequent recollection of their nocturnal disturbances, even if complex and prolonged. Some parasomnias are simply ‘annoying’ to the bed partner, with no obvious adverse consequences to the sleeping subjects themselves.

Parasomnias are generally classified according to the state of sleep from which they arise.

Parasomnias at the wake–sleep transition

Hypnic jerks are common slightly unsettling experiences that occur just at the point of sleep onset. Likened to a sudden sensation of falling through space, an abrupt and generalised ‘body twitch’ occurs, occasionally in association with brief a sensory symptom such as a ‘flash’ or ‘explosion’. Although this can cause alarm and produce a degree of sleep onset insomnia, drug treatment is rarely appropriate. Given the possible link to sleep deprivation, advice on sleep hygiene and reassurance are usually sufficient and appropriate.

A rare condition termed propriospinal myoclonus may also cause vigorous jerks whilst lying flat at the point of sleep onset. The movements tend to cause flexion of the trunk and occur on a nightly basis as the subject drifts to sleep. Insomnia may result and be difficult to treat. Occasionally a spinal cord lesion may generate these movements and spinal magnetic resonance imaging is indicated.

Often on a background of head banging or body rocking as young children, some adults may exhibit persistent rhythmical movements as they are dropping off to sleep. This may be viewed as a comforting habit or an aid to sleep onset but, surprisingly, movements also occur during deep sleep and disturb the bed partner. Typical patterns of movement include rolling of the body or slow rhythmical shaking of the head from side to side. Drug treatment is rarely helpful.

Parasomnias from deep non-REM (slow wave) sleep

A spectrum of abnormal behaviours may occur from the deepest stages of non-REM sleep (slow wave sleep) and may affect up to 2% of adult populations. There is usually a history of parasomnia activity in childhood which can range from simple sleep talking or walking to agitated night terrors. A positive family history is also frequently seen.

As with children, this type of parasomnia is thought to reflect partial arousal from the first period of deep non-REM sleep. The subject may appear awake and have open eyes but there is little or no conscious awareness. Recollection of the disturbance the following morning is usually minimal. Behaviours are often benign but can be surprisingly complex and involve navigation through rooms or the use of familiar household objects.

Non-specific fear or agitation is a common association and may cause the subject to shout out or rapidly leave the bed. There is rarely true dream recall although a sense of a ‘presence’ in the room may be reported. Other common themes are visual hallucinations of spiders, for example, or simply a sense of impending doom. In this state, injurious behaviours may result in the rush to leave the room or aggression can be displayed to bed partners, particularly by male subjects.

Compared to children, during non-REM sleep parasomnias adults tend to display more instinctive behaviours that are goal-orientated. Uninvited sexual advances to a bed partner may cause marital disharmony or, at the very least, embarrassment. Similarly, nocturnal eating or cooking with no clear conscious control can be hazardous and also cause excessive weight gain. Some male subjects will regularly urinate in inappropriate places, such as cupboards.

The cause of non-REM sleep parasomnias remains obscure. Although unproven, an abnormality of neurodevelopment or maturation involving the sleep centres in the brainstem appears most plauible. Particularly in adults, factors that deepen sleep (typically sleep deprivation) or inhibit full arousal from sleep (short-acting hypnotic agents) can occasionally trigger parasomnias. Equally, factors that potentially cause partial arousals from deep sleep are often relevant. Examples include an uncomfortable sleeping environment such as a sofa, snoring or extraneous noise, a full bladder, or excessive leg movements. Anecdotally, increased stress or having an ‘overactive mind’ can be a relevant precipitant (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1 Predisposing and precipitating factors in non-REM parasomnias (‘arousal disorders’).

| Important factors | Comment | |

| Predisposition for non-REM parasomnias (e.g. sleepwalking) | Abnormal maturation of ‘sleep centres’ in brain during early childhood The process is presumably under genetic control | Proposed mechanism to explain abnormal partial arousals from deep non-REM sleep There is commonly a strong family history of non-REM sleep parasomnias although the nature may vary across generations (e.g. night terrors versus benign sleepwalking); Relevant genetic linkage studies are awaited |

| Potential triggers or precipitants | Deeper non-REM sleep than usual | Prior sleep deprivation or previous night shift work are common factors causing deeper non-REM sleep as a ‘rebound’ phenomenon Deep non-REM sleep becomes less pronounced by early adulthood potentially explaining why many ‘grow out’ of sleepwalking, for example |

| Arousals to full wakefulness inhibited | Common examples include CNS depressant drugs such as short-acting hypnotics, alcohol, major tranquilisers or lithium, often in combination | |

| Increased arousals from deep non-REM sleep | Environmental stimuli such as loud noises can be used experimentally to induce sleepwalking in predisposed adults; Any cause of ‘secondary insomnia’ can potentially fuel arousals that lead to a parasomnia Snoring and medical disorders such as oesophageal reflux may predominate in adults In children, fevers are common triggers | |

| Psychological distress | Increased anxiety levels are often reported as a trigger although systematic evidence is lacking |

The role of alcohol as a potential trigger for non-REM parasomnia activity is controversial, particularly if violent or antisocial behaviour has occurred, potentially leading to medico-legal consequences. Significant alcohol intake before bed can certainly influence the nature and quality of any subsequent sleep but no rigorous studies have addressed its specific effects on sleepwalking in those predisposed to the phenomenon. In clinical practice, some subjects report a definite link to excessive alcohol intake whereas others claim it makes them less likely to exhibit disturbances. It seems probable that the secondary effects of excessive alcohol may be particularly important as possible triggers for parasomias. For example, associated sleep deprivation, increased snoring, a full bladder or sleeping in an uncomfortable environment such as the sofa may increase the likelihood of a parasomnia occurring.

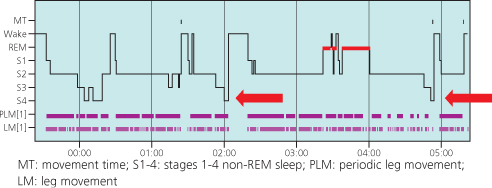

It is rare for investigations to help greatly either in the diagnosis or management of non-REM parasomnias unless there is a co-morbid sleep disorder fuelling the situation. It is not uncommon for clinicians to wrongly suspect nocturnal epilepsy as an alternative diagnosis, which may justify overnight polysomnographic recording (Chapter 8 gives more discussion on this differential diagnosis). In a sleep laboratory, it is rare to capture parasomnia events although several sudden arousals from deep non-REM sleep to apparent wakefulness during the night, even in the absence of confusion, may act as a useful marker in those predisposed to the phenomenon (Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 The overnight hypnogram of a young adult subject experiencing frequent agitated parasomnias. The arrows at around 2:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m. indicate two sudden arousals from deep (stage 4) non-REM sleep with brief apparent awakenings and associated confusion. Such arousals are commonly seen in those predisposed to non-REM sleep parasomnias such as sleepwalking.

In this case, there are very frequent periodic leg movements as seen on the PLM trace. These leg movements were important as triggers for the abnormal partial arousals that led to parasomnia activity. Drug treatment of the excessive leg movements resolved the parasomnia.