The Principles of Clinical Assessment in General Psychiatry

John E. Cooper

Margaret Oates

Introduction

This chapter is focused on the needs of the clinician in a service for general adult psychiatry, who has to carry-out the initial assessment of the patient and family, working either in the context of a multi-disciplinary team or independently. Within this quite wide remit, the discussion is limited to general principles that guide the practice of all types of psychiatry. The chapter does not include the special procedures and techniques also needed for assessment of children and adolescents, the elderly, persons with mental retardation, persons with forensic problems, and persons requiring assessment for suitability for special types of psychotherapy.

It is assumed that the reader has already had significant experience of clinical psychiatry and has completed the first stages of a postgraduate psychiatric training programme. Therefore details of the basic methods recommended in commonly used textbooks or manuals of instruction for obtaining and recording information on essentials such as the history, personal development, mental state, and behaviour of the patient are not included in this chapter.(1)

Three topics have been given special attention. These are assessment by means of a multi-disciplinary team, the trio of concepts diseases, illness, and sickness, and the development of structured interviewing and rating schedules. The first two have a special connection that justifies emphasis in view of the recent increase in multi-disciplinary styles of assessment. For instance, when different members of the team appear to be in disagreement about what should be done, it is usually a good idea to ask the question: ‘What is being discussed—is it the patient’s possible physical disease, the patient’s personal experience of symptoms and distress, or the interference of these with social activities?’ It will then often become apparent that the issues in question are legitimate differences in emphasis and priority of interest, rather than disagreements. The third topic is given prominence in order to illustrate some aspects of the background of the large number of such schedules (or ‘instruments’) that are now available. They are usually given the shortest possible mention in research reports, but since most advances in clinical methods and service developments come from studies in which an assessment instrument has been used, clinicians should know something about them.

The aim of the initial clinical assessment is to allow the clinician and team to arrive at a comprehensive plan for treatment and management that has both short-term and longer-term components. The achievement of this will be discussed under the following headings.

Concepts underlying the procedures of assessment

Contextual influences on assessment procedures

Assessment as a multi-disciplinary activity

Instruments for assessment

The condensation and recording of information

Making a prognosis

Reviews

Writing reports

Concepts underlying the procedures of assessment

The separation of form from content, and from effects on activities

In psychiatric practice more than in other medical disciplines, the key items of information that allow the identification of signs and symptoms of psychiatric disorders are often embedded in a mixture of complaints about disturbed personal and social relationships, together with descriptions of problems to do with work, housing, and money. These complaints and problems may be a contributing cause or a result of the symptoms of psychiatric disorders, or they may simply exist in parallel with the symptoms. A preliminary sorting out into overall categories of information is therefore essential.

The distinction between the form and the content of the symptoms is particularly important, together with the differentiation of both of these from their effects upon the functioning of the patient (function is used here in a general sense as applying to all activities, in contrast to the specific meaning given to it in the classification of disablements). This differentiation is discussed in Chapter 1.7, so only a brief mention is needed here.

The presenting complaint of the patient is often the interference with functions, but enquiry about the reasons for this should then reveal the contents of the patient’s thoughts and feelings. The form of the symptoms (i.e. the technical term, such as phobia or delusion used to identify a recurring pattern of experience or behaviour known to be important) allows the identification of the psychiatric disorder. Knowledge of the effects on functions is essential for decisions about the management of patient and family, and is an important aspect of the severity of the disorder.

This sorting into different types of information often implies a conflict of priorities during the interview. The clinician must be seen to acknowledge the concerns and distress of the patient, but also must ask questions that will allow the identification of symptoms. Learning to balance this conflict of interest is an essential part of clinical training, and has been well recognized by previous generations of descriptive psychiatrists, including Jaspers. The separation of the social effects of a symptom from the symptom itself is also a necessary part of the assessment process. Further comments on this and related issues have been made by Post(2) and by McHugh and Slavney.(3)

Categories of information: subjective, objective, and scientific

Is there such a thing as a truly objective account of events? If ‘objective’ is intended to mean absolutely true and independent of all observers, the answer must be negative. Students and trainee psychiatrists often come to psychiatric clinical work from medical and surgical disciplines where they have been encouraged to ‘search for the facts’ with the implication that ‘true’ facts exist. They may need to be reminded that the supposed facts of all medical histories, even those of clearly physical illnesses, depend upon the perceptions, opinions, and memories of individuals who may give different versions of the same events at different times.

‘Objective’ has several shades of meaning in ordinary usage, but in clinical assessment it’s most useful meaning is that an account of an event or behaviour is based on agreement between two or more persons or sources. In contrast, ‘subjective’ can be used to indicate that the account comes from only one person. Objective information is likely to be safer to act upon than subjective, so efforts should always be put into raising as much as possible of the information about a patient into the objective category. Nevertheless, many of the most important symptoms in psychiatry can only be subjective, since they refer to the inner experience of the one person who can describe them.

When assessing the reliability and usefulness of other types of information, such as the results of treatment or possible explanations of causes, a further useful distinction can be made between objective defined as above and ‘scientific’, taking this to mean that systematic efforts have been made to obtain evidence based upon comparisons (or ‘controls’) which demonstrate that one explanation can be preferred out of several possibilities that have been considered.

Simple definitions such as these are useful in clinical discussions, but it must be remembered that in the background are many complicated and unsolved problems of philosophy and semantics. Some of these suggestions on the status of information in clinical work are based upon the writings and clinical teaching of Kraupl Taylor.(4)

Disease, illness, and sickness

These concepts have existed in the medical and sociological literature for many years, and are best regarded as useful but inexact concepts that refer to different but related aspects of the person affected, namely pathology (disease), personal experience (illness), and social consequences (sickness), respectively.(5) They are useful as a trio because they serve as a reminder that all three levels should be considered in a clinical assessment, even though for different patients they will vary greatly in relative importance. There are no simple answers to questions about how they are best defined and how exactly they are related to each other, but time spent on these issues is not wasted because they reflect quite naturally some of the different interests and priorities of the different health professions (and are therefore often the basis of different viewpoints put forward by various members of a multi-disciplinary team).

Another reason for being familiar with these concepts is that in legal and administrative settings, simple and categorical pronouncements about the presence of mental illness or mental disease and their causes and effects may be required whatever the medical viewpoint might be about the complexity of these concepts.

Clinicians of any medical discipline know from everyday experience that the complete sequence of disease—illness—sickness does not apply to many patients. Although disease usually causes the patient to feel ill and the state of illness then usually interferes with many personal and social activities, in practice there are many exceptions. Potentially serious physical, biochemical, or physiological abnormalities (disease) may be discovered in surveys of apparently healthy persons before any symptoms, distress, or interference with personal activities (illness) have developed, and some patients may have either or both of illness and sickness (interference with social activities) without any detectable disease.

A number of sociologists, anthropologists, and philosophers have joined psychiatrists in trying to define mental illness and mental health, but without achieving much clarification. Aubrey

Lewis(6) and Barbara Wootton,(7) although writing from the different contexts of clinical psychiatry and sociology, both arrived at the conclusion that neither mental illness nor mental health could be given precise definitions, although they are useful terms in everyday language (and the same applies equally to physical health and physical illness).

Lewis(6) and Barbara Wootton,(7) although writing from the different contexts of clinical psychiatry and sociology, both arrived at the conclusion that neither mental illness nor mental health could be given precise definitions, although they are useful terms in everyday language (and the same applies equally to physical health and physical illness).

More positive conclusions have resulted from attempts to define disease, in that Scadding (a general physician) has suggested that it should be defined as an abnormality of structure or function that results in ‘a biological disadvantage’.(8,9) This seems reasonable if one is dealing only with conditions that have a clear physical basis, but if applied in psychiatry it implies that, for instance, behaviours such as homosexuality that reduce the likelihood of reproduction would have to be regarded as diseases alongside infections, carcinoma, and suchlike. This seems to be stretching a traditional concept too far, and different approaches clearly need to be explored.

One way forward is to accept that simple definitions and concepts encompassed by one word cannot cope with complicated ideas such as disease or health, and to take care to differentiate between definitions of these as concepts in their own right, and attempts to develop models of medical practice. The debate noted above refers to concepts of health, disease, and disorder, and it has been continued more recently with respect to psychiatry in two quite extensive reviews, in terms of the types of concepts,(10) and of their possible contents.(11) What follows below is better regarded as about models of medical practice, and two points are suggested as a basis for the discussion. First, more than one dimension or aspect of the person affected always needs to be included in descriptions of health status. Second, models of medical practice and thinking do not necessarily have to start with the assumption that physical abnormalities (diseases) are the basic concept from which all others are derived.

Regarding the first point (of more than one aspect or dimension), soon after the contribution of Susser and Watson(5) noted above, Eisenberg, a psychiatrist with social and anthropological interests,(12) made a plea for all doctors, but particularly psychiatrists, to recognize the importance of appropriate illness behaviours in addition to giving the necessary attention to the diagnoses and treatment of serious and dangerous disorders.(13) He gave special emphasis to the need to minimize problems that may arise from discrepancies between disease as it is conceptualized by the physician and illness as it is experienced by the patient: ‘when physicians dismiss illness because ascertainable disease is absent, they fail to meet their socially assigned responsibilities’. A similar model with a more overtly three-dimensional structure usually referred to as ‘bio-psychosocial’ has also been described by Engel.(14) and also by Susser.(15) Historically, all these can be regarded as variations on and explicit developments of a theme that has been accepted implicitly by generations of psychiatrists influenced by the ‘psychobiology’ of Adolf Meyer and his many distinguished pupils, manifest in the importance given to the construction of the traditional clinical formulation.

The second point, to do with the disease level not being the best starting point for conceptual models of medical practice, is of more recent and specifically psychiatric origin. Both Kraupl Taylor(16) and, more recently, Fulford(17) give detailed arguments for the conclusion that the illness experience of the patient is the most satisfactory starting point from which to develop a model of medical practice. Taylor presents his case as a matter of logic, and Fulford works through lengthy philosophical and ethical justifications. This new viewpoint has the virtue of starting with the encounter between patient and doctor, which has the strength of being one of the few things that is common to all types of clinical practice. In Taylor’s terms, by describing symptoms and distress the patient arouses ‘therapeutic concern’ in the doctor and so first establishes ‘patienthood’. Whether or not a diagnosis is reached or a disease is later found to be present, and whether or not the social activities of the patient are also interfered with, are other issues of great importance, but they do not diminish the primary importance of the first interaction; in this, both patient and doctor play their appropriate roles according to their personal, social, cultural, and scientific backgrounds.

If medical training and practice are guided by this model, there is no interference with the essential obligation of the doctor to identify and treat any serious disease that may be present. However, a parallel obligation to satisfy the patient and family that the illness (comprising complaints and distress) and the sickness (interference with activities) have also been recognized and will be given attention, is equally clear.

How to answer questions by the patient and family about whether the patient has a mental illness or not, and what this implies, needs careful discussion. Within a multi-disciplinary team it is usually best for the team to reach early agreement on a particular way of describing the patient’s illness so that conflicting statements will not be made inadvertently by different members if asked about it. This is because the patient or family may expect this type of statement, and not because distinctions between, for instance, mental illness and physical illness, or between nervous illness and emotional upset, are regarded as fundamental from a psychiatric viewpoint. This difficult issue will be made easier if something about the patient’s ideas about the nature and implications of terms such as ‘mental illness’ and ‘nervous breakdown’ is always included as part of the initial assessment information. Similarly, all members of the team need to be familiar with the concept of illness behaviour and the way this is determined by cultural influences(18) (see Chapter 2.6.2).

The diagnostic process: disorders and diagnoses

Psychiatrists learn during their general medical training that the search for a diagnosis underlying the presenting symptoms is one of the central purposes of medical assessment. This is because if an underlying cause can be found, powerful and logically based treatments may be available. But even in general medicine, as Scadding pointed out ‘the diagnostic process and the meaning of the diagnosis which emerges are subject to great variation … the diagnosis which is the end-point of the process may state no more than the resemblance of the symptoms and signs to a previously recognized pattern’.(8,9) In psychiatry, ‘may’ becomes ‘usually’, and this has been recognized by the compilers of both ICD-10 and DSM-IV, in that these are presented not as classifications of diagnoses, but of disorders. These classifications use similar definitions of a disorder; the key phrases in ICD-10 are ‘the existence of a clinically recognizable set of symptoms or behaviour associated in most cases with distress and with interference with personal functions’, and in DSM-IV ‘a clinically significant behavioural or psychological syndrome or pattern that occurs in an individual and that is associated with present distress or disability …’.

The use of such broad definitions is necessary because of the present limited knowledge of the causes of most psychiatric disorders, and a similarly limited understanding of processes that underlie their constituent symptoms. To avoid overoptimistic assumptions, there is much to be said for psychiatrists avoiding the use of the term ‘diagnosis’ except for the comparatively small minority of instances in which it can be used in the strict sense of indicating knowledge of something underlying the symptoms. A consequence of this viewpoint is that the currently used ‘diagnostic criteria’ in both these classifications should be relabelled as ‘criteria for the identification of disorders’.

In spite of this, it must be accepted that the patient and family are likely to expect statements to be made about the cause of their distress and symptoms. The members of all human groups expect their healers to discover the causes of their misfortunes (i.e. to make a diagnosis), and to provide remedies. This is so whether the group is a sophisticated and scientifically oriented modern society, or a non-industrialized society that relies on ethnic healers and folk remedies. The obvious relief of a patient or family on the pronouncement of an ‘official’ diagnosis is often evident in any type of healing activity, even though the diagnostic terms themselves mean very little. The pronouncement of an official diagnosis is taken to show that the doctor knows what is wrong, and therefore will be able to provide successful treatment or advice. If the diagnosis is expressed in terms that the patient can understand, it will have additional power as an explanatory force.

The readiness of ethnic healers and practitioners of complementary (or alternative) medicine to provide a diagnosis and treatment in terms that have a meaning and therefore a powerful appeal to their customers is probably one of the main reasons for their continued survival and popularity alongside scientifically based medicine. This is a separate issue from the question of whether or not the treatments of complementary practitioners are successful in the sense of having effects that could be demonstrated by means of a controlled clinical trial.

Within psychiatry and clinical psychology, the medical habit of searching for a diagnosis has at times been misunderstood as an unjustified preoccupation with the presence of physical disease as a cause of mental disorders. This was most marked in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s, expressed particularly in the writings of Menninger in which the diagnostic process and attempts to classify patients were dismissed as a waste of time.(19) This viewpoint ignores two points made here and by many others; first, the choice of a diagnostic term is only one part of the overall process of assessment that leads also to a personal formulation. Second, any assessment of a person, whether made as statements about psychodynamic processes, as statements about structural and biochemical abnormalities, or as statements about interference with activities, is unavoidably an act of classification of some sort.

Concepts of disablement

Disablement will be used here as an overall term to cover any type of interference with activities by illness. This is often of more concern to the patient than the symptoms of the illness itself, since the fear of long-term dependence upon others is usually present, even though not voiced in the early stages. The question arises whether to leave the description and assessment of disablement to different members of the team as it arises in various forms, or whether in addition to encourage reference to one of the systematic descriptive schemes that are now available. Even if not used as fully as their authors intend, these have the merit of serving as checklists or reminders for the whole team, to ensure that the many different effects of the illness have been considered.

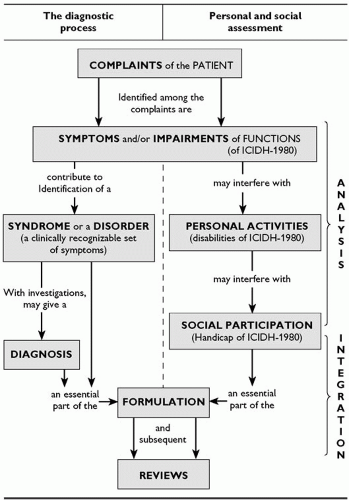

Two widely used descriptive schema are the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF),(22) and a broadly similar framework described by Nagi(23) that is often used in the United States, particularly by neurologists. These are best regarded as descriptive conceptual frameworks rather than classifications, sharing a basic structure of several levels of concepts. For the ICIDH, these are functioning, disability, and the contextual factors (both environmental and personal) relevant to what is being assessed. These terms and concepts are defined in the manuals published by WHO Geneva. The ICF is published as both a short and a long version, and it is probably wise for interested users to start by examining the short version. As noted in Fig. 1.8.1.1, these three concepts can be put alongside the sequence of ideas that leads from complaints, through symptoms to the identification of disorders or diagnoses. This may represent a causal sequence in some individuals, and this is clearest in acute physically based illnesses. But for many patients encountered in psychiatric practice, whose illnesses often have prominent social components, causal relationships may be absent or even in the opposite direction. For instance, sudden bereavement, i.e. loss of a social relationship, may be the clear cause of interference with the ability to perform daily activities (disability), and also of uncontrolled weeping (an impairment of the normal control of emotions). Social handicaps can also be imposed unjustifiably by other persons, as when a patient who is partly or fully recovered from long-standing psychiatric illness and quite able to work is refused employment due to the prejudice of a potential employer.

Many mental health workers find that to use a scheme such as Fig. 1.8.1.1 or the ICF helps to clarify how different aspects of a patient’s problems fit together. Similarly, the different members of the team may be able to see more clearly how their activities with the patient and family complement one another, since the different concepts in the framework correspond approximately with the interests of different health disciplines. Social workers will focus on assessment of work and social relationships, occupational therapists will have a special expertise in the assessment of daily activities, and clinical psychologists are skilled in the assessment of cognitive and other psychological functions. Researchers in the various health disciplines have naturally devised rating scales that reflect their own interests and ideas, independently of the ICF or other overall schema, but it is usually found that such scales correspond quite closely with one or other of the concepts just discussed. The reluctance of both researchers and clinicians to adopt a standard set of terms to cover the various levels or concepts continues to be a problem; the reader needs to be aware that the terms impairment, disability, and handicap are often used synonymously by different authors.

The description of social and interpersonal relationships is in principle included in comprehensive schemas such as the ICF and that of Nagi, but many separate instruments that cover relationships in great detail have been devised over the years by psychotherapists, family therapists, and others.(24, 25 and 26)

The sequence of assessment: collection, analysis, synthesis, and review

As information accumulates and is discussed, several different but related aspects of the patient and the illness have to be kept in mind. Good psychiatric practice is a part of what is sometimes referred to as ‘whole-person medicine’ in which at different times the contrasting but complementary processes of both analysis and synthesis of the information available will be needed. The patient must be seen both as an individual with a variety of attributes, abilities, problems, and experiences, and as a member of a group that is subject to family, social, and cultural influences; at different stages in the process of assessment each of these aspects will need separate consideration.

Analysis is needed to identify those attributes, experiences, and problems of the patient and the family that might require specific interventions by different members of the team. This must then be followed by several types of synthesis (or bringing together of information) to enable attempts to understand both subjective and objective relationships between the patient and the illness. First, possible interventions must be placed in order of priority for action. Second, the whole programme needs to be reviewed at intervals so as to assess progress and decide about any additional interventions that are required. At these times of review, and particularly towards the end of the whole episode of illness, global statements about ‘overall improvement’, or changes in ‘quality of life’ may be additional useful ways of summarizing and evaluating what has been happening from the viewpoint of the patient.

From complaints to formulation

Figure 1.8.1.1 demonstrates how the information contained in the complaints presented by the patient needs to be sorted out into different conceptual categories so that it can form the basis of actions by the various members of the multi-disciplinary team.

The top box represents the complaints. Unpleasant symptoms are likely to head the list, but inability to do everyday activities or a description of problems with relationships may well come first. Symptoms that give a clue to disorders, diagnoses, and possible treatments may not be identified without close questioning by someone who knows what to ask about.

The second box indicates that the complaints need to be sorted out into symptoms and impairments (an impairment in this sense is interference with a normal physiological or psychological function, as explained below). Some complaints are both symptoms and impairments: symptoms because it is known that they can contribute towards the recognition of an underlying diagnosis or towards the identification of a disorder, and impairments because they indicate measurable interference with the function of a part of the body or of a particular organ. For instance, inability to remember the time of the day is a symptom (disorientation in time) that may contribute towards a diagnosis of some kind of dementia. It is also an impairment of cognitive functioning that is likely to interfere with the performance of everyday activities such as getting up and going to bed at the correct time, and organizing housework.

The left-hand side of Fig. 1.8.1.1 represents the progress towards the identification of a disorder and perhaps even an underlying diagnosis. These are important concepts because they may indicate useful treatments and likely eventual outcomes. The right-hand side shows the progression from impairment of functions of parts of the body or organs, through interference with personal and daily activities to interference with participation in social activities.

A clinical assessment is not complete until all the components of both sides of Fig. 1.8.1.1 have been considered. In doing this, the different components and the two pathways of concepts will need to be given widely varying emphasis for different patients, and also for the same patient at different times. For instance, if there is a physical cause for a disturbance of behaviour, an accurate diagnosis of this will lead to the best possible chance of rapid and successful treatment. In contrast, if a disturbance of social behaviour has its origin in personal relationships or has been imposed upon the patient by the social prejudices of others, the correct diagnostic category is unlikely to add much. An assessment of social networks and supportive relationships will be more relevant to deciding upon useful actions.

Life events and illness

For clarity, the right-hand side of Fig. 1.8.1.1 is given in a very compressed form, but in practice it is likely to need dividing into several components. The possibility of discovering relationships in time between life events and the onset of symptoms or interference with activities, particularly if repeated, should always be kept in mind, since this may be relevant to management plans and the

assessment of prognosis. The best guide to this will be a lifechart. The opinions of patients and families about the causes of illness must be listened to with respect, while bearing in mind that the attribution of illness to the effects of unpleasant experiences is a more or less universal human assumption that often has no logical justification. Clinicians have to arrive at their own conclusions about such relationships by means of experience, common sense, and some acquaintance with research findings. Researchers seeking robust evidence on this topic are faced with a very difficult task, since the assessment of vulnerability to life events is a surprisingly complicated and controversial issue. The leading method in this field is the Life Events and Difficulties Schedule developed by Brown and Harris; a bulky training manual has to be mastered during a special course, and this then serves as a guide to an interview which may last for several hours. The length and detail of these procedures illustrate well the technical and conceptual problems that have to be faced.(27, 28 and 29)

assessment of prognosis. The best guide to this will be a lifechart. The opinions of patients and families about the causes of illness must be listened to with respect, while bearing in mind that the attribution of illness to the effects of unpleasant experiences is a more or less universal human assumption that often has no logical justification. Clinicians have to arrive at their own conclusions about such relationships by means of experience, common sense, and some acquaintance with research findings. Researchers seeking robust evidence on this topic are faced with a very difficult task, since the assessment of vulnerability to life events is a surprisingly complicated and controversial issue. The leading method in this field is the Life Events and Difficulties Schedule developed by Brown and Harris; a bulky training manual has to be mastered during a special course, and this then serves as a guide to an interview which may last for several hours. The length and detail of these procedures illustrate well the technical and conceptual problems that have to be faced.(27, 28 and 29)

Psychodynamics and the life story

‘Psychodynamics’ refers in a general sense to the interactions between discrete life events, personal relationships, and personality attributes, in addition to its use to cover internal psychological processes (such as defence mechanisms and coping strategies). All of these need to be examined when trying to understand which of several possible causes of an illness at a particular time is the most likely.

A mixture of knowledge about local social and cultural influences and more technical psychological issues is needed for this appraisal of the patient’s life story, and suggestions about different components of the overall pattern may well come from different members of the team.

The internal psychodynamics of the patient often need to be considered in detail, and one way to do this would be to construct a subdivision of the right-hand side of Fig. 1.8.1.1 to show interpersonal relationships and psychodynamic processes. In some patients a major conclusion of the initial assessment will be that these aspects are paramount, indicating the need for referral to a specialist psychotherapy service. The assessment of suitability for specific forms of psychotherapy and cognitive behavioural approaches are dealt with in section 6.

Contextual influences on assessment procedures

The place of assessment should not be regarded as automatically fixed in the outpatient or other clinical premises. One or more assessment interviews at home should be considered,(30) since the patient and family may feel much more at ease and therefore likely to express themselves more freely in familiar surroundings, but with the proviso that privacy may be more difficult to achieve. The assessor will often be surprised how much useful information about the home and family circumstances is gained from an interview at home, even when there appeared to be no special reason for this at first. In addition, the behaviour of both the patient and family members in the clinic or hospital is often different from that observed in familiar home surroundings. There are also obvious advantages to both assessment and care at home for mothers who have psychiatric disorders in the puerperium.(31)

Interviews on primary care premises are also often appreciated by patients who dislike going to hospitals of any sort, and the ease of consultation with the general practitioner is an additional advantage. The adoption of regular visits by a consultant psychiatrist to primary care premises as a major element in cooperation between psychiatrists and general practitioners is a style of work that seems to be spreading, with advantages to all concerned.(32)

Privacy of interviewing and confidentiality of what is discussed needs careful consideration; there are few absolute rules, but the following points of procedure should be explained clearly to both patient and relatives from the start. First, the patient and any member of the family should know that if they wish they are entitled to speak to the doctor in private, and they must be able to feel that what they say will not be conveyed to any other member of the family unless they request this. Second, in addition to the usual rules of professional secrecy, the patient must agree not to question other family members about what they said to the doctor, and vice versa. These may seem to be elementary points to trained professionals, but they are often not appreciated by patients or relatives who may be in fear of each other, or at least apprehensive about the reaction of the other on learning that statements they might construe as critical have been made about them. These are all points by which trust is established and maintained between patient and doctor, and for the same reason any attempts by relatives to seek interviews on condition that the occasion is kept secret from the patient should be firmly resisted.

An interpreter should always be sought if the patient cannot speak fluently in the language of the interviewer. Mental health professionals who can also act as interpreters are increasingly available nowadays due to the presence of almost all communities of sizeable ethnic minorities. Because of the issues of confidentiality noted above, a professional of the same sex as the patient should always be preferred to family members when interpretation is needed.

Language barriers are usually, but not always, accompanied by a cultural difference. The interviewer must remember that the concept of a private interview between two strangers in which personal and often unpleasant events and experiences are discussed freely comes from ‘middle-class western’ culture, and is not necessarily shared by persons from other cultures. A discussion of this point before the interview with a mental health professional familiar with the patient’s background will help the interviewer to determine what to aim at in terms of intimate or possibly distressing information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree