Anatomy

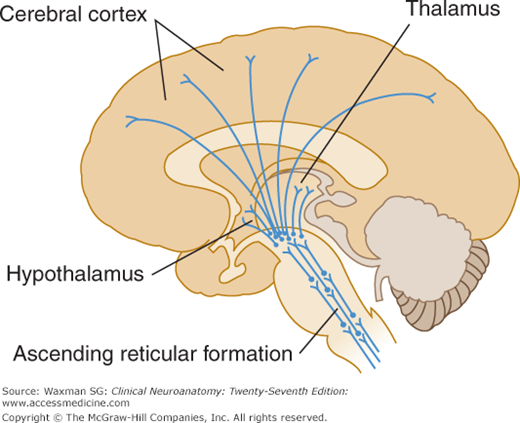

The reticular formation plays a central role in the regulation of the state of consciousness and arousal. It consists of a complex network of interconnected circuits of neurons in the tegmentum of the brain stem, the lateral hypothalamic area, and the medial, intralaminar, and reticular nuclei of the thalamus (Fig 18–1). Many of these neurons are serotonergic (using serotonin as their neurotransmitter), or noradrenergic. Axons from these nonspecific thalamic nuclei project to most of the cerebral cortex, where, as noted later, they modulate the level of activity of large numbers of neurons. The term reticular formation itself derives from the characteristic appearance of loosely packed cells of varying sizes and shapes that are embedded in a dense meshwork of cell processes, including dendrites and axons. The reticular formation is not anatomically well defined because it includes neurons located in diverse parts of the brain. However, this does not imply that it lacks an important function. Indeed, the reticular formation plays a crucial role in maintaining behavioral arousal and consciousness. Because of its crucial role in maintaining the brain at an appropriate level of arousal, some authorities refer to it as the reticular activating system.

In addition to sending ascending projections to the cortex, the reticular formation gives rise to descending axons, which pass to the spinal cord in the reticulospinal tract. Activity in reticulospinal axons appears to play a role in modulating spinal reflex activity and may also modulate sensory input by regulating the gain at synapses within the spinal cord. The reticulospinal tract also carries axons that modulate autonomic activity in the spinal cord.

Functions

Regulation of arousal and level of consciousness is a generalized function of the reticular formation. The neurons of the reticular formation are excited by a variety of sensory stimuli that are conducted by way of collaterals from the somatosensory, auditory, visual, and visceral sensory systems. The reticular formation is, therefore, nonspecific in its response and performs a generalized regulatory function. When a novel stimulus is received, attention is focused on it while general alertness increases. This behavioral arousal is independent of the modality of stimulation and is accompanied by electroencephalographic changes from low-voltage to high-voltage activity over much of the cortex. The nonspecific thalamic regions project to the cortex, specifically to the distal dendritic fields of the large pyramidal cells. If the reticular formation is depressed by anesthesia or destroyed, sensory stimuli still produce activity in the specific thalamic and cortical sensory areas, but they do not produce generalized cortical arousal.

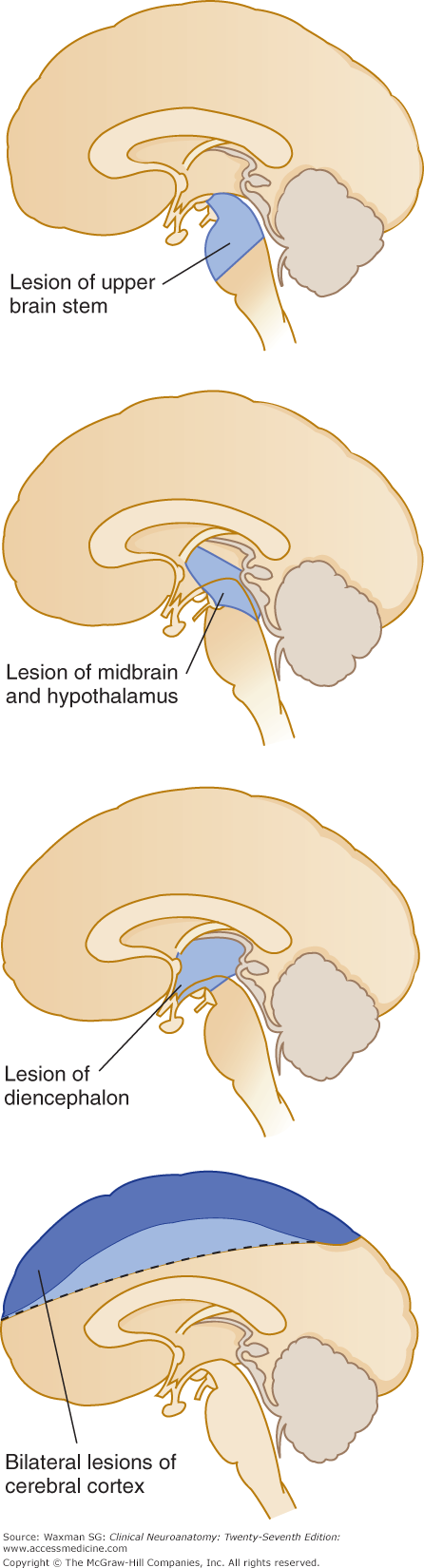

Many regions of the cerebral cortex produce generalized arousal when stimulated. Because different attributes of the external world (eg, color, shape, location, sound of various external stimuli) are represented in different parts of the cortex, it has been suggested that “binding” of neural activity in these different areas is involved in conscious actions and conscious recognition. Arousal, which is abolished by lesions in the mesencephalic reticular formation, does not require an intact corpus callosum, and many regions of the cortex can be injured without impairing consciousness. The cortex and the mesencephalic reticular activating system are mutually sustaining areas involved in maintaining consciousness. Lesions that destroy a large area of the cortex, a small area of the midbrain, or both produce coma (Fig 18–2).

The loss of consciousness in syncope (fainting) is brief in duration and sudden in onset; more prolonged and profound loss of consciousness is described as coma. A patient in a coma is unresponsive and cannot be aroused. There may be no reaction, or only a primitive defense movement such as corneal reflex or limb withdrawal, to painful stimuli. Stupor and obtundation are still lesser grades of depressed consciousness and are characterized by variable degrees of impaired reactivity. Acute confusional states must be distinguished from coma or dementia (see Chapter 22). In the former case, the patient is disoriented and inattentive and may be sleepy but reacts appropriately to certain stimuli.

Coma may be of intracranial or extracranial origin. Intracranial causes include head injuries, cerebrovascular accidents, central nervous system infections, tumors, and increased intracranial pressure. Extracranial causes include vascular disorders (shock or hypotension caused by severe hemorrhage or myocardial infarction), metabolic disorders (diabetic acidosis, hypoglycemia, uremia, hepatic coma, addisonian crisis, electrolyte imbalance), intoxication (with alcohol, barbiturates, narcotics, bromides, analgesics, carbon monoxide, heavy metals), and miscellaneous disorders (hyperthermia, hypothermia, severe systemic infections). The Glasgow Coma Scale offers a practical bedside method of assessing the level of consciousness based on eye opening and verbal and motor responses (Table 18–1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree