CHAPTER 5 The social context of behaviour

The material in this chapter will help you to:

Introduction

In Chapter 4 it was argued that the biomedical model of health was inadequate in explaining the patterns of mortality and morbidity for populations and individuals. A biopsychosocial model of health was proposed and a brief outline of the social determinants of health was presented. This chapter takes the ‘social’ aspects of the biopsychosocial model of health and examines the evidence, debates and theories that argue that illness and disease for individuals, populations and nations is not simply a matter of germs and viruses (biomedical) or individual psychology and behaviour (biopsychological), but a complex interaction between the social system of a given society and the individual (biopsychosocial) and their particular genetic inheritance (biomedical).

Traditionally there has been a stand-off between biomedical, biopsychological and social models of health. This stand-off is counterproductive and contrary to the evidence. Over the past three decades particular population groups within affluent nations have failed to make the promised biomedical and health promotion gains (Raphael et al 2005). Evidence of this has been obtained from long-term studies of health differences between sections of society in Western nations (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006). Comparisons of health outcomes between individuals and nations have shown that although baseline improvements in life expectancy, infant mortality and death from childhood injury have occurred in countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and the United States, there are marked differences in health status between individuals in these countries, as well as marked differences between countries (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006).

These differences appear to be the result of life chances and the kind of social institutions and welfare policies a country has. For example, in the Scandinavian countries, while the gains in health have mirrored those in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and the United States, the population as a whole has made further health gains as the percentage of people on low incomes is lower than in English-speaking countries (Raphael 2006). This is best explained through the kinds of social policies in place in the Scandinavian countries.

The social model of health and the social determinants of health

The social model of health

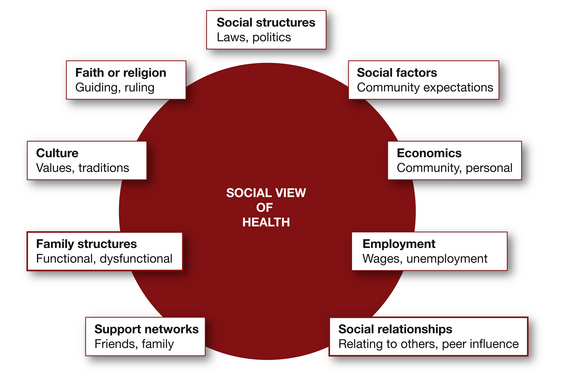

There are two major components to a social model of health. First, health and illness are seen to be partly attributed to the social circumstances of individuals and populations. These social circumstances include their level of income in absolute terms and relative to other people in the population, their education, employment, gender, culture and status. Epidemiological evidence provides clear proof of differences in health status between individuals based on these factors. For instance, research on the social gradient (one of the social determinants of health) explains how the perception of one’s social position can be a predeterminant of a chronic stress response that may create long-term physical and psychological illness (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006).

A social model of health identifies the social determinants of health

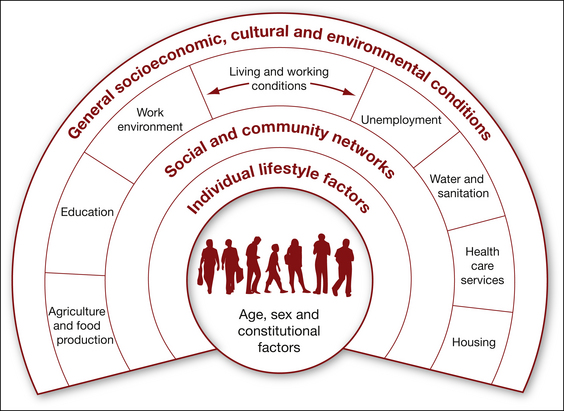

The factors that make up the social model of health are known as the social determinants of health (SDH). These SDH explain the differences in health outcomes between individuals and populations. Each social determinant of health describes a set of circumstances that influences a particular health outcome. The SDH listed in Figure 5.2 were developed by Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991). In their model the social determinants include three layers. The first or outer level includes the socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions; the second layer includes agricultural and food production, education, the work environment, unemployment, sanitation and water supplies, healthcare services and housing. Dahlgren and Whitehead add a third layer that suggests that social networks also impact on health outcomes. It is not until the fourth layer that the individual and their behaviour are listed. This diagram is not simply a listing of features in a society. The authors are suggesting that the outer layers are features of a society that determine the health of its members and that each layer shapes the next inner layer.

Other theorists have suggested alternative social determinants. These include childhood poverty, differences in social class between groups, stress (Marmot 2001), social exclusion, unemployment (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006), type of work (Bartley et al 2006), lack of social support (Stansfeld 2006), social patterns of addiction (Jarvis & Wardle 2006), quality and quantity of food supplies (Robertson et al 2006) and transport (McCarthy 2006).

Figure 5.2 and the brief outline above have highlighted how complex and interdependent the SDH are. The SDH also provide a means of addressing inequalities in health outcomes in a manner that the biomedical model of health cannot. For example, by providing affordable, reliable, public transport to outer suburbs, a number of the social determinants could be addressed. This is because transport contributes to a reduction in social isolation, increases the chance of poor people entering a city for employment and the opportunities to accessing health services can be increased. Thus, one government policy action can have a flow-on effect.

CLASSROOM ACTIVITY

AUSTRALIAN STUDENTS

Using the social health atlas for your state or territory (see http://www.publichealth.gov.au/publications/a-social-health-atlas-of-australia-[second-edition]—volume-1:-australia.html), click on the fact sheet and read one of the identified areas, such as children, youth or women. Examine this fact sheet and be prepared to bring information to class for your tutorial for discussion. Select facts that highlight the social determinants of health.

FOR NEW ZEALAND STUDENTS

Go to the Social Report and click on ‘Health Report’ at http://www.socialreport.msd.govt.nz/health/index.html

Be prepared to come to class with information on the relationship between health, ethnicity and age. You could explore such relationships in terms of life expectancy, suicide and obesity.

The history and the formation of the social determinants of health

The acknowledgment of the importance of the social model of health was demonstrated by the formation of the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1948. The WHO constitution clearly outlines the need for a whole-of-government approach to health. Unfortunately, in the 30 years that followed governments around the world pursued a technologically driven model of health that only addressed the downstream, curative approach of health (Solar & Irwin 2007), thus failing to direct health policy towards the upstream, structural determinants of health. The term structural is used here to make the point that the problem lies in the organisation of a society or group, not in individual behaviour.

The 1978 Alma Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care and the Health for All movement attempted to revive action on the SDH through promoting a social model of health. While many governments in principle embraced the Health for All concepts and acknowledged the importance of incorporating a broader view of health that addressed aspects such as housing, education and employment on health (Solar & Irwin 2007), neo-liberal economic policies were gaining favour. The neo-liberal policies encouraged governments to reduce public spending on health, housing, employment and other welfare services thus turning away from a social model.

However, work defining and refining the social model and the SDH has continued. The previously mentioned deficits in the biomedical model of health were highlighted by the seminal work of McKeown and Illich (Solar & Irwin 2007) and the Black Report in the United Kingdom (Turrell et al 1999). The work of McKeown, Illich and Black and his colleagues was instrumental in highlighting the gaps in health outcomes of population groups that were directly related to social conditions (Black et al 1980, Kelly et al 2006, Turrell et al 1999). The SDH have again risen to prominence in light of the mounting evidence that the efficiency models of the neo-liberal economic policies are exacerbating the health differences between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’ such that, in Australia, there is now a 20-year mortality difference between those individuals in the highest socioeconomic group and those in the lowest (RACP 2005). In 2003 WHO created the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (Kelly et al 2006). The commission delivered its final report in 2008 which has placed the SDH and their ongoing refinement and definition firmly on the policy and research agenda (WHO 2008).

Why support a social model of health? The social justice argument and the implications for government policy

Health as a human right

As health professionals and as a society it is important to qualify our notions of health and the availability of health services. One way of achieving this is through defining and understanding health as a core value or human right. Values can be defined as: ‘the beliefs of a person or group which contain some emotional investment or held as sacrosanct; while core is the most essential or vital part of some idea’ (Morales & Gilner 2002). The idea of health as a core value is espoused in the notion of health as a human right, as this places health as a central ideal and a ‘right for all’ (Lie 2004).

If health is a right for all humans then it falls outside the individual to solely provide for it and becomes a joint responsibility of the individual and the government or society to provide. As a right for all, the provision of health becomes an entitlement and thus falls on governments to ensure (Baum 2005). By viewing health as a human right it enables governments to legislate to protect those rights and enables service providers to broaden the constructs of health to be inclusive of social conditions such as housing and education.

Health as a right ensures equity

When governments incorporate health as a human right into their policy agenda the advancement of health equity is also ensured (Lie 2004). Where health is a human right health services are provided regardless of people’s socioeconomic position, gender, educational level, ethnicity or religion (Baum 2005, Solar & Irwin 2007). To charge people for health services is to charge them for something that is regarded as a right. Unfortunately, in many countries where healthcare is not free, factors such as socioeconomic position determine the level of health that can be enjoyed by an individual (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006).

Theoretical models for understanding the social determinants of health

If morbidity and mortality rates for a population are a result of social conditions it is important to identify what these SDH are and to introduce policy that will reduce the impact. One approach is to examine each SDH for how it impacts on health status and to make recommendations for the kind of social policy required to eliminate the negative effects (Raphael 2006). A number of social epidemiologists have taken this approach by identifying a range of social determinants they view as important in the higher rates of morbidity and mortality of some population groups.

The socioeconomic and political context

The first factor impacting on the SDH is the socioeconomic and political context of a society. While this refers to the impact of the political and cultural system of a society on the health of the population, it is best understood in concrete terms as the impact of economic, social and public policy on the life chances of the population. Examples of economic policy include those governing the industrial relations such as rates of pay and the casualisation of work for young people, including hours of work. Social policies include those dealing with welfare issues such as access to housing, disability, old age and sickness benefits, while public policies cover issues such as access to education, the provision of healthcare and utilities such as power, water and communications. Policies that enable poor people to access resources such as power, water, education and healthcare, or protect workers from discrimination, or support workers during times of unemployment go some way towards achieving a reduction in inequality.

The health impact of such policies is illustrated in the differences in mortality rates between the United Kingdom (free universal healthcare to all), the United States (private system with access to free healthcare means tested in its extension to the poor and elderly only) and Australia with a mixed public–private system. In 2007 the probability of dying under five years of age was 6/1000 in the United Kingdom and Australia and 8/1000 in the United States. These differences, while not stark, are explained partly as a result of healthcare policy where access to care is free in Australia and the United Kingdom, but not so in the United States (World Health Statistics 2007)

The SDH can be further categorised into those determinants that are ‘structurally’ produced and addressed through changes at a societal level via policy intervention and those determinants that act more directly on individuals and are ‘intermediary’ determinants that can be addressed through community health programs and individual health interventions and behaviour change (Solar & Irwin 2007). Dividing the SDH into these two categories makes health promoting action clearer. The necessary policy for creating a healthy environment becomes evident whether this is through policy directed towards alleviating poverty (structural) or programs to help individuals change their behaviour (intermediary). The pathway between the structural and intermediary also goes some way to integrating the social and psychological.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree