The Sodium Amytal and Benzodiazepine Interview and Its Possible Application in Psychogenic Movement Disorders

Susanne A. Schneider

Kailash P. Bhatia

ABSTRACT

Sodium amytal, a medium-acting barbiturate, was first described in 1861. Since then it has been popular for its effectiveness in facilitating diagnostic and therapeutic interviewing, and we have reviewed its use here. Early studies that found particular utility in catatonia mainly focused on the responses of psychiatric patients. Amytal has also been found to be useful in conversion reactions, including those manifesting as movement disorders. Beneficial effects in posttraumatic torticollis and amelioration of posture and pain have been demonstrated. Furthermore, sodium amytal can help to differentiate conversion disorder from malingering and factitious behavior.

Combining the amytal interview with the use of video feedback was reported to lead to full recovery and a restoration of lost body function, and may be a useful tool in movement disorder patients.

Overall, sodium amytal is a relatively safe and useful drug facilitating diagnostic and therapeutic interviewing. However, there is a relative paucity of studies for the use in psychogenic movement disorders. Further studies including controlled investigations are needed. The amytal or benzodiazepine interview may also be a useful tool to increase our understanding of the pathophysiology of psychogenic movement disorders.

INTRODUCTION

As far back as 1861, Griesinger had described notable improvements in psychotic states after narcotic- or anesthetic-induced sleep (1,2). The synthesis of sodium amytal, a medium-acting barbiturate, by Schonle and Moment in 1923 led to the facilitation of diagnostic and therapeutic interviewing (2,3).

In 1930, Bleckwenn first reported the use of sodium amytal to produce “sleep and physical rest in psychotic patients” (4,5). In order to “break down the stubborn insomnia of the more severe psychoses” and to “simplify the management and materially shorten the course of the illness,” he administered repeated injections of sodium amytal by means of general anesthesia to the patients (6,7). He noticed “a lucid interval for 1 to 2 minutes before the patient fell asleep” during which the patient “was rational and had complete insight into his condition” (2). Barbiturates have a sedating effect, and sodium amytal became the drug of choice to assist interviewing due to its rapid induction time and the elicited effect of released speech. These initial observations led to the practice of the use of sodium amytal for both diagnostic and therapeutic interviewing for over 75 years.

In the early 1960s, the recognition of barbiturate dependency and the introduction of alternative drugs like benzodiazepines, however, led to a decline in the use of amytal. In recent years, there has been fresh interest in amytal interviewing as a tool in clinical practice. Beneficial diagnostic use and successful treatment of conversion disorders, especially those with movement disorders like abnormal or fixed postures, have been described. Videotaping of amytal interviews has become possible and, in fact, is recommended, as such videos can be used as feedback in following sessions. They give evidence to the patient of the ability to move fixed or paralyzed body parts and may help to improve such symptoms.

Thus, amytal-assisted interviews may have a role in the diagnosis and therapy of psychogenic movement disorders. In this review, we will look at the historical aspects, method of use, and suggested clinical indications for amytal/benzodiazepine-assisted interviews and also review the aspect of its potential use for psychogenic movement disorders.

HISTORICAL ASPECTS

Following Bleckwenn mentioned above (4,5), Lindemann used subanesthetic doses of amytal to promote self-disclosure in both normal and abnormal individuals (8). He was the first to demonstrate possible benefits of the interview in a nonpsychotic population, as well (8,9). In 1935, an influential study by Thorner described the beneficial effects of sodium amytal in catatonia (10). He studied 18 patients, ten of whom, previously mute, began talking. Waxy flexibility (cerea flexibilitas) was successfully ameliorated in all five affected cases. Twelve of 14 patients with previously compromised eating and nourishment “requested food and ate ravenously.”

The event of World War II led to a marked increase in the use of sodium amytal. Battle traumatized soldiers would develop a variety of neurotic symptoms to escape the rigors of trench warfare. At this time, Horsely (1936) introduced a new technique termed “narcoanalysis.” This defined a popular seven-stage procedure used to treat acute, traumatic neuroses (7,11). Retrieval and reintegration of “repressed memories” were achieved. In 1945, Grinker and Spiegel carried the work further. They used “narcosynthesis” to encourage “abreaction”—the free expression and release of previously repressed emotion (2,12). They outlined the importance of an early beginning with treatment before symptoms became fixed (9). At the technique’s peak in popularity in 1949, Tilkin enthusiastically described “the future of narcosynthesis [as] infinite and possibilities [being] endless” (2,13). Narcosuggestion (14) and narcocatharsis were other new terms to make their appearance at that time.

One dubious application included the use of sodium amytal as a so-called “truth serum” for interviewing suspected criminals and also for prediction of response to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in schizophrenia (15).

By the 1960s, however, the use of sodium amytal started to wane due to a number of reasons. First, the risk of barbiturate dependency was increasingly recognized. Second, the appearance of new drugs, specifically neuroleptics like chlorpromazine in 1952 to treat catatonic schizophrenia or psychosis had a major effect on the decline in the use of sodium amytal interviewing (2). In addition, tricyclic antidepressants became available. Concurrently, benzodiazepines as safer alternative drugs to sodium amytal were introduced in those cases that needed it. Benzodiazepines were suggested as the preferred agent due to their possible reversibility by the GABA antagonist flumazenil and their broader therapeutic index.

CHEMICAL AND PHARMACOLOGIC PROFILE

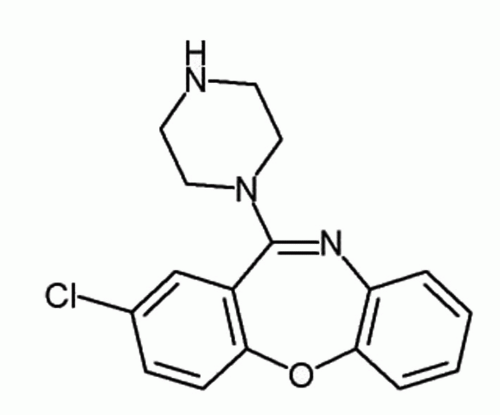

Sodium amytal is a medium-acting barbiturate. Other names are amobarbital and isoamylethylbarbiturate. Chemically, amytal is 5-ethyl-5-(3-methylbutyl) barbituric acid or 5-ethyl-5-(3-methylbutyl)-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-pyrimidinetrione (16) (Fig. 28.1). As a consequence of their lipophilic chemical structure, barbiturates reach the brain quickly and need to be titrated carefully. As a mediumacting agent, amytal sedates more gradually; on the other hand, narcosis is more persistent (17). It depresses the cerebral cortex leading to changes in social behavior and intellectual operations (17). Due to this suppression of

higher functions, the subject becomes less observant and more suggestible.

higher functions, the subject becomes less observant and more suggestible.

STUDIES AND SUGGESTED INDICATIONS FOR AMYTAL INTERVIEWS

Most of the early studies were either open-label or had relatively few cases, and there was a relative paucity of controlled studies focusing on sodium amytal interviewing. It was not until the 1960s that the first controlled studies to evaluate the usefulness of sodium amytal were attempted. Kavirajan, in a detailed review, analyzed the literature on the therapeutic and diagnostic studies using sodium amytal (15), and we will document some of the main findings below. In 1954, Weinstein and Malitz asserted the expediency of sodium amytal to identify organic brain injury, where it would cause disorientation and denial of illness, which would not occur in healthy subjects (15,18).

Around the same time, in a placebo-controlled trial, Shagass studied and outlined the usefulness of sodium amytal interviewing to differentiate between neurotic and psychotic depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, organic psychosis, and hysteria (19). He based his conclusions on the observation of the “sedation threshold” which defined the dose at which an individual manifested speech changes and specific EEG abnormalities (15,19).

Also, several controlled studies for catatonia were attempted, some of which had a favorable conclusion (20,21). Elkes observed increased accessibility, mobilization, and speech in catatonic patients who were given sodium amytal (20). Elkes also noted that saline in controls did not lead to a response. In contrast, Dysken published a more sceptical study in 1979 regarding the effects and utility of the amytal interview (22,23). In a placebo-controlled clinical trial, where subjects acted as their own controls, he investigated the diagnostic role in acute psychotic patients. Dysken perceived both the drug and the placebo to be clinically useful. He found no significant superiority of amytal over placebo in promoting disclosure of diagnostically useful information (23). Dysken was uncertain to what extent the benefit was a specific pharmacologic effect of sodium amytal or the result of the patient’s expectation that a special drug would facilitate talking. In conclusion, his findings would argue against widespread use of sodium amytal as a diagnostic tool in psychiatric illness (15). On the whole, various studies regarding catatonia were attempted over the years (24,25), but no unambiguous result was achieved. Kavirajan outlined a consensus from his review. He cited a study by Tollefson, who found that catatonic patients with primary psychiatric illness would at least transiently show an increased verbal expression. In contrast, those with “organic” catatonia would worsen or remain unchanged (15,26).

Similar results were found in patients with confusion (15,27,28). Amytal helped clear the sensorium in patients with functional confusion, while organic confusion was increased (27).

Subsequently, a “general rule” was described claiming that organic and nonorganic patients would show different reactions to administration of sodium amytal (15). However, it was pointed out that not all the cases of hysteria might improve (15,27).

Studies also aimed at evaluating the efficacy of sodium amytal compared to other agents and saline. Again, some studies were more favorable than others.

Hain, who used amobarbital, methamphetamine, hydroxydione, or saline for interviewing in psychoneurosis, found no significant differences among the different agents in promoting emotional expression or recall (15, 29). However, he noted that amytal was associated with less emotional change than was the placebo. Smith reanalysed the same data in a follow-up paper. He found that abreaction during the interview did not correlate with subsequent clinical change (30). In a later paper, he stressed that interviewer effects reached significance in measures of interview quality and outcome (31).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree