The special psychiatric problems of refugees

Richard F. Mollica

Melissa A. Culhane

Daniel H. Hovelson

While the forced displacement of people from their homes has been described since ancient times, the past half-century has witnessed an expansion in the size of refugee populations of extraordinary numbers.(1,2) In 1970, for example, there were only 2.5 million refugees receiving international protection, primarily through the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). By 2006, UNHCR was legally responsible for 8.4 million refugees. In addition, it is conservatively estimated that an additional 23.7 million people are displaced within the borders of their own countries. Although similar in characteristics to refugees who have crossed international borders, internally displaced persons do not receive the same protection of international law. Adding all refugee-type persons together, the world is forced to acknowledge the reality that over the past decade more than 10 000 people per day became refugees or internally displaced persons.

The sheer magnitude of the global refugee crisis, the resettlement of large numbers of refugees in modern industrial nations such as Canada, the United States, Europe, and Australia, and the increased media attention to civil and ethnic conflict throughout the world has contributed to the medical and mental health issues of refugees becoming an issue of global concern. This chapter will focus on a comprehensive overview of the psychiatric evaluation and treatment of refugees and refugee communities. Although this mental health specialty is in its infancy, many scientific advances have been made that can facilitate the successful psychiatric care of refugee patients.

Definition

The definition of a refugee as outlined in the 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees is presented in Box 7.10.1.1.(3) A person or persons who has passed over from one country into another seeking protection from violence and who cannot return to his country of origin because of fear of persecution or injury is considered a refugee according to international law.

The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees was drawn up by the United Nations parallel to the creation of UNHCR. This Convention and the subsequent 1967 Protocol establishes

international law for the definition of refugees as well as the protection accorded to them. It also articulates the important principle of non-refoulement (Box 7.10.1.1), which states that no refugee can be returned to his or her country of origin or any other location where there is any probability that he or she will be harmed. These legal definitions indicate that a refugee is not an economic migrant or a traditional immigrant. Sadruddin Aga Khan, in a seminal report, was one of the first High Commissioners to acknowledge the human rights violations that are primarily responsible for the generation of refugee populations.(4) Corresponding to these international covenants, the international community has focused on the protection of refugees. There are two components to protection that are classically viewed by UNHCR as an essential aspect of its mandate. These two elements include protection against:

international law for the definition of refugees as well as the protection accorded to them. It also articulates the important principle of non-refoulement (Box 7.10.1.1), which states that no refugee can be returned to his or her country of origin or any other location where there is any probability that he or she will be harmed. These legal definitions indicate that a refugee is not an economic migrant or a traditional immigrant. Sadruddin Aga Khan, in a seminal report, was one of the first High Commissioners to acknowledge the human rights violations that are primarily responsible for the generation of refugee populations.(4) Corresponding to these international covenants, the international community has focused on the protection of refugees. There are two components to protection that are classically viewed by UNHCR as an essential aspect of its mandate. These two elements include protection against:

Box 7.10.1.1 Definations according to the 1951 convention and 1967 protocol relating to the status of refugees

Article 1—Definition of the term ‘refugee’ A(2) [Any person who] … owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence …, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it. (As amended by Article 1(2) of the 1967 Protocol.)

Article 33—Prohibition of expulsion or return (refoulement) (1) No contracting state shall expel or return (refouler) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.

1 ongoing violence and potential injury to the refugee including being denied proper asylum and involuntary repatriation;

2 lack of adequate food, water, clothing, and other forms of material assistance.

The UN Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in December 1948 and the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment adopted in December 1984 extends the basic principles of refugee protection and asylum, and reaffirms the principle of non-refoulement. In most refugee crises, not withstanding the political and military barriers to protection, UNHCR and the international community strive to offer refugees a safe asylum and basic humanitarian aid.

Trauma and torture

By definition, most refugees have experienced traumatic life events of extraordinary brutality. Since the Second World War, empirical studies have investigated the relationship between mass violence, the refugee experience, and psychiatric morbidity. The earliest research focused on survivors of the Nazi concentration camps.(5,6,7,8) Shortly after the Second World War, Eitinger and his colleagues gave a detailed account of their medical and psychiatric examinations of concentration camp survivors. They postulated that the traumatizing process had a dual nature. They described the somatic traumas of captivity, such as head injury, hunger, and infections, as leading to a ‘psycho-organic syndrome’, and the predominately psychological traumas as leading to other psychiatric disorders such as depression. Thygesan’s studies of concentration camp survivors in Denmark revealed similar results.(9, 10) These early pioneering investigations of the psychosocial sequelae of the Nazi concentration camps established a preliminary baseline of traumatic outcomes for future generations of refugees, many of whom had experienced the trauma of similar experiences in Cambodia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and elsewhere.

Increasingly, civilian populations carry the burden of ethnic conflict and mass violence. It is now estimated that more than 80 per cent of casualties caused by the recent violence in Africa, Asia, and Europe have primarily affected non-combatants.(11) Extensive research has revealed the major trauma events experienced by refugee populations fall into the eight groups below:

1 material deprivation

2 war-like conditions

3 bodily injury

4 forced confinement and coercion

5 forced to harm others

6 disappearance, death, or injury of loved ones

7 witnessing violence to others

8 brain injury

Every refugee situation will have a range of traumatic events that will fall into each of these categories that are unique or characteristic of a specific conflict. It is essential that the specific types of violence experienced by a given refugee population are well known to the psychiatric clinician who can use this knowledge to assess potential traumatic outcomes.(12) In addition to many unique forms of violence occurring in different refugee settings, the meaning of violent events also differs across cultures. Anecdotal, clinical, and epidemiological evidence suggests that certain categories of refugee trauma are more potent than others in producing psychiatric morbidity and other traumatic outcomes. Brain injury, sexual violence, torture and other forms of bodily injury, coercion, and forced confinement have great potential of causing psychiatric harm in refugees exposed to these events. Consistent with indicators of the ‘potency’ of specific trauma events, there evidence of a dose-effect relationship between cumulative trauma and psychiatric symptoms.(13) The personal aspects of human suffering associated with specific types of trauma, such as the murder of a child or the disappearance of a family member are still relatively undefined but obviously very difficult.

Many refugees have actually experienced torture. Recent research states that the most significant finding in the last 7 years may be that either torture has become more prevalent worldwide or the total number of events reported has increased, likely as a result of advocacy and elevated media attention.(14) After 25 years of research on treatment work with torture survivors, still no consensus exists for effective interventions within the field.

Conceptual model of traumatic outcomes

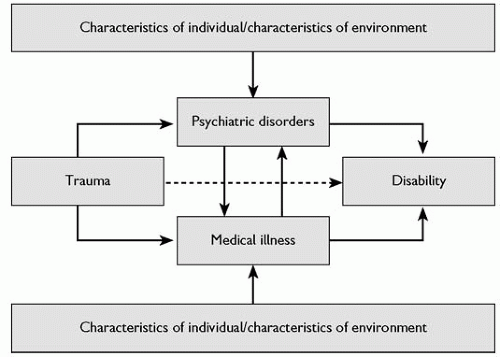

Research on refugees has revealed the persistence of negative health and social outcomes decades after their initial experience of violence and dislocation. Emergence of standardized criteria for psychiatric diagnoses and disability and the demonstrated ability to elicit trauma events through simple screening instruments in culturally diverse populations have allowed evidence to accumulate suggesting a model of traumatic outcomes associated with the refugee experience. This model is primarily based upon the classic epidemiological triad which describes the interaction between host (i.e. the refugee), agent (i.e. traumatic life experiences), and environment (e.g. refugee camp) in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders.(15, 16) This model, illustrated in Fig. 7.10.1.1, allows equal attention to be given to all aspects of the refugee experience.

The model in Fig. 7.10.1.1 has three major elements. First, it suggests that the major medical outcomes associated with the refugee experience are medical illness, psychiatric disorders, and disability. Second, trauma and the personal and environmental characteristics of the refugee describe the major risk factors associated with violent outcomes. Third, the direction of the causal arrows in the model do not imply a lack of reciprocal relationships where none is indicated; instead they indicate what most investigations consider

to be the most dominant causal relationship. Despite its limitations, this simple conceptual model can provide the psychiatric professional with a scheme for approaching the refugee patient from either a clinical or public health perspective. The importance of the socio-cultural and political context unique to each refugee situation and its impact on each of the model’s pathways cannot be overstated, since refugees come from diverse cultural groups and political experiences.

to be the most dominant causal relationship. Despite its limitations, this simple conceptual model can provide the psychiatric professional with a scheme for approaching the refugee patient from either a clinical or public health perspective. The importance of the socio-cultural and political context unique to each refugee situation and its impact on each of the model’s pathways cannot be overstated, since refugees come from diverse cultural groups and political experiences.

Health status and medical illness

Refugees experience many diseases and chronic debilitating conditions, such as starvation and landmine injuries that have both immediate and long-term effects on their physical health. Every refugee situation involves many unique but common acts of violence leading to major medical sequelae. For example, gender-based violence and rape, which were instruments of ethnic cleansing in the Balkans, resulted in pregnancy, medically complicated self-administered abortions, and sexually transmitted diseases.(17) Extensive documentation of refugee survivors of torture describes the medical sequelae of torture and the causal link between refugee trauma and medical mortality and morbidity over time.

Throughout the process of migration, refugees are frequently exposed to infectious diseases and physical or psychological trauma that can have a profound impact on their overall health and well-being. Refugees are at increased risk for diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, and often encounter significant barriers to employment and health care when attempting resettle. For these reasons, programmes implemented in the refugees’ country of resettlement designed to improve health-seeking behaviours and overall self-care can have a positive, lasting impact on refugees’ physical and mental health.(18)

Psychiatric symptoms and illness

Observations since Kinzie et al.(19) and Mollica et al.(20) first diagnosed PTSD in Cambodian refugees, have made the cultural validity of PTSD seem almost certain. However, this reality does not negate the importance of culture-specific symptoms related to trauma that are independent of PTSD criteria. Recent large-scale epidemiological studies of refugee populations have confirmed the high prevalence of major depression and PTSD in Western (e.g. Bosnian(21)) and non-Western (e.g. Cambodian(22) and Bhutanese(23)) refugee communities. The mental health impact of major depression, which presents both as a comorbid disorder with PTSD and alone, is chronic, severely disabling and demands the attention of the clinician working with refugees. Longitudinal data indicates that 45 per cent of Bosnian refugees who met criteria for PTSD, depression or both continued to meet criteria for these disorders 3 years later.(24) Similar results were found in a longitudinal study of Cambodian refugees 20 years after resettling in the United States.(25) As with Western populations, depression in refugees tends to be under-diagnosed and can be expressed as somatic complaints. A study of Vietnamese refugees showed high prevalence based on self-report, but high rate of physician under-diagnosis. Most patients with depression (95 per cent) presented with physical complaints.(26) These finding underscore the importance of depression screening especially in the primary care setting.

New research indicates that there may be memory problems in refugees with PTSD. When asked to recall traumatic events refugees with PTSD reported an increased number of traumatic or torture events over their baseline report, as compared to those with other psychiatric disorders who showed no change or decreases in number of events reported.(27) Substance use disorders are often overlooked in refugee populations but are often comorbid with PTSD.(28) Early in the 1980s reports of Hmong refugees using opium emerged.(29) Substance use disorders have been shown to have a delayed presentation of 5 to 10 years after the initial settlement of the refugee.(30) However, substance use disorders may vary by population. One recent study of Cambodian refugees in the United States reports low rates of alcohol use in the past 30 days.(31) Screening for substance use disorders especially in primary care is important. Complex grief reaction and chronic insomnia are also prevalent in this population.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree