CHAPTER 42 The Surgical Management of Cerebellopontine Angle Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

Meningiomas comprise up to 15% of adult intracranial tumors. These tumors, usually benign and slow-growing, may affect various anatomic structures in the posterior fossa and specifically the cerebellopontine angle. The term cerebellopontine angle (CPA) meningioma has been used widely to describe meningiomas that share a common location, that is, occupancy of the CPA, although these tumors may have diverse origins with regard to the site of dural attachment, which can be outside the CPA.1

The first report of a tumor that would now be classed as a CPA meningioma was by Rokitansky2 in 1856. Virchow3 later described a psammoma originating from the posterior lip of the acoustic meatus. In 1928, Cushing and Eisenhardt4 reported on seven patients with meningiomas “simulating acoustic neuromas,” emphasizing the high surgical risk in dealing with these tumors. Several surgical series of posterior fossa meningiomas involving the CPA have been reported since then. Microsurgical series were reported by Yasargil,5 Sekhar and Janetta,6 Ojemann,7 Al-Mefty,8 Haddad and al-Mefty,9 Harrison and al-Mefty,10 Matthies and colleagues,11 Samii and Ammirati,12 and Samii and colleagues.13,14

SURGICAL PROCEDURE

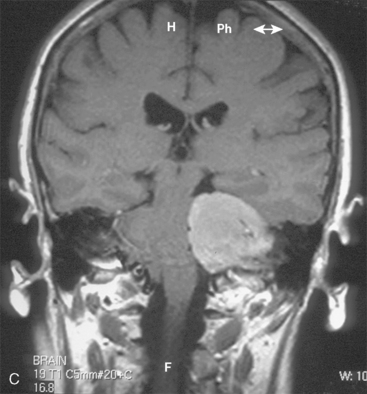

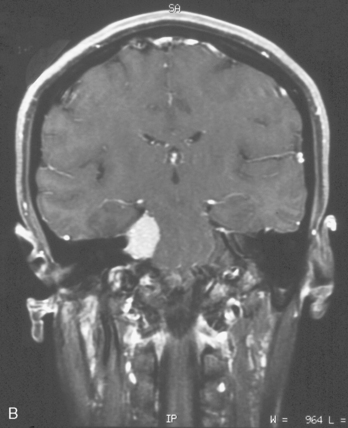

CPA meningiomas may arise from any area of the dura on the posterior surface of the petrous bone (Fig. 42-1A–C). Four general categories of tumor are found, depending on where they arise and their relationship to the VIIth and VIIIth nerve complex:

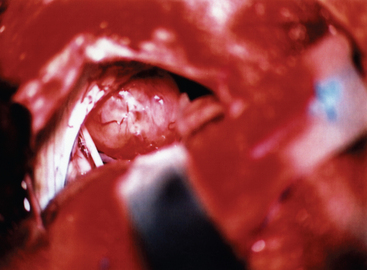

At this stage, the operating microscope is introduced into the surgical field. Great care should be taken to preserve the arachnoid planes during the dissection, as this helps to protect the adjacent cerebellum and cranial nerves. The margins of the tumor are identified, and the tumor margins are dissected away from the adjacent cerebellum and vascular and neural structures, with care being taken to preserve the arachnoid. Any feeding vessels are coagulated and divided, but great care must be taken to preserve all vascular and neural structures that may be densely adherent to the tumor capsule (Fig. 42-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree