The Value of Bone Scintigraphy and CT Scan in Diagnosis and Treatment of Active Spondylolysis in Elite Athletes

J. Sys

J. Michielsen

Low back pain accounts for 5% to 8% of athletic injuries (1). Spondylolysis is one of the major causes of low back pain in young athletes (1,2,3,4,5,6). Incidences of spondylolysis of over 40% have been reported in studies among female gymnasts, football players, weightlifters, wrestlers, and divers (7,8,9,10). In these studies, no distinction was made between acute and chronic spondylolysis. Micheli and Wood found spondylolytic stress fractures or acute spondylolysis of the pars interarticularis in 47% of 100 adolescent athletes (11). In adolescent and young adult athletes, special attention should be given to fatigue fractures of the pars interarticularis because of their possible evolutive nature (4,11,12,13,14,15).

Although genetic and racial factors may predispose an individual to spondylolysis (16,17,18), the most generally favored theory is that spondylolysis is a fracture caused by mechanical stress and that the mode of failure is fatigue (19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27). In general, the prevalence of spondylolysis is not higher in athletes than it is in nonathletes, although participation in sports involving large stress reversals in the pars interarticularis appears to be associated with disproportionately higher rates of spondylolysis (3). The mechanical etiology of this fatigue fracture is controversial, and many experimental studies have been carried out to determine the fatigue strength of the pars interarticularis and to delineate the movements causing failure (12,28,29,30,31,32). Experiments on cadaveric lumbar motion segments have shown that full flexion and extension movements bend the inferior articular process sufficiently to cause a fatigue fracture of the pars interarticularis (33). The likelihood of fatigue failure would be greater in activities that require alternating flexion and extension of the lumbar spine, because this would involve large stress reversals in the pars interarticularis (22,33,34). Movements of this type occur in gymnastics, volleyball, tennis, pole vaulting, cricket, etc. Also, the clinical outcome of nonoperative treatment seems to be unfavorable in athletes participating in these high-risk sports (35)

Athletes with spondylolysis present with pain during certain performance activities. The onset of pain can be either acute or progressive. The pain may become more chronic and dull with time. Clinical examination frequently reveals paraspinal muscle spasm and hamstring tightness (13).

TERMINOLOGY

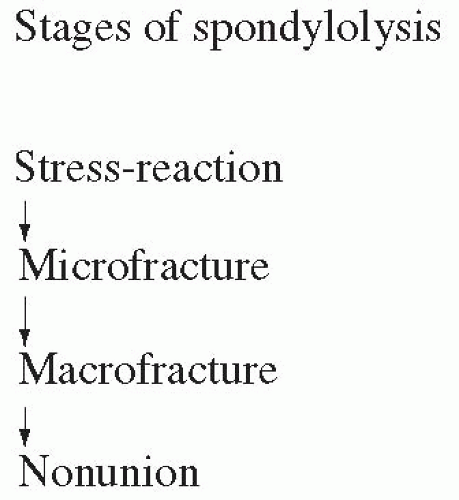

It may be assumed that a stress reaction, a microfracture, a macrofracture, and spondylolisthesis can be the consecutive stages of the same overuse injury at the pars interarticularis (4,13,15,36,37,38) (Fig. 7.1). No single imaging or scintigraphic technique allows

differentiation between these stages. Several authors have discerned early, progressive, and terminal stages, either with standard radiography (x-ray) (15), computed tomographic (CT) scan (4), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (37,39,40). Rather than using the terms acute or chronic, early or late, we prefer using the terms active and inactive, with reference to the appearance on bone scintigraphy.

differentiation between these stages. Several authors have discerned early, progressive, and terminal stages, either with standard radiography (x-ray) (15), computed tomographic (CT) scan (4), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (37,39,40). Rather than using the terms acute or chronic, early or late, we prefer using the terms active and inactive, with reference to the appearance on bone scintigraphy.

Sys et al. have advocated differentiation between bilateral and pseudobilateral spondylolysis (Fig. 7.2) according to the scintigraphic appearance (41). When tracer uptake is present on both sides of one vertebra and uptake is clearly asymmetrical, the lesion is called pseudobilateral. In pseudobilateral spondylolysis, only the fracture with a highly increased uptake on bone scintigraphy is considered recent or active. The fracture on the other side is an older or scintigraphically less active lesion. The terms active and inactive provide a better understanding of the true nature of the lesion. The term acute spondylolysis is related to the appearance of symptoms rather than to the age of the lesion(s). From this study, we know that these do not always correlate.

Lesions can be classified as unilateral, bilateral, or pseudobilateral, according to their scintigraphic appearance (41). The relative number of counts at one side of a lesion needs to be compared with the number of counts on the other side. The average count from 10 transverse cuts is calculated for each side with the center of the vertebral body as a reference. When the ratio of the most active side to the least active side is between 0.8 and 1.19, the lesion is considered bilateral; when the ratio is more than 2.0, the lesion is considered unilateral. Lesions with a ratio between 1.2 and 2.0 are considered pseudobilateral.

DIAGNOSIS AND FOLLOW-UP

Early radiographic features of spondylolysis and prespondylolytic stress reactions such as vertebral anisocoria have been described extensively (42,43). Nevertheless, the sensitivity of different lumbosacral radiographic views in the detection of spondylolysis is limited (4,36,41,44,45). Bone scintigraphy is the most sensitive tool for early diagnosis of acquired spondylolysis in young athletes (4,19,36,38,46,47,48,49). With single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), spatial separation of overlapping bony structures is possible: The anatomic localization of a hot spot is improved and sensitivity is increased (8,38,44,46). A scintigraphic active pars interarticularis defect is associated with a healing process, which may elicit pain, whereas a normal bone scan in the presence of a radiographically demonstrable pars defect is consistent with a healed (fibrous), pain-free nonunion or pseudarthrosis (27,38,44,46,47).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree