Theories of Personality and Psychopathology

4.1 Sigmund Freud: Founder of Classic Psychoanalysis

4.1 Sigmund Freud: Founder of Classic Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalysis was the child of Sigmund Freud’s genius. He put his stamp on it from the very beginning, and it can be fairly stated that, although the science and theory of psychoanalysis has advanced far beyond Freud, his influence is still strong and pervasive. In recounting the progressive stages in the evolution of the origins of Freud’s psychoanalytic thinking, it is useful to keep in mind that Freud himself was working against the background of his own neurological training and expertise and in the context of the scientific thinking of his era.

The science of psychoanalysis is the bedrock of psychodynamic understanding and forms the fundamental theoretical frame of reference for a variety of forms of therapeutic intervention, embracing not only psychoanalysis itself but various forms of psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapy and related forms of therapy employing psychodynamic concepts. Currently considerable interest has been generated in efforts to connect psychoanalytic understandings of human behavior and emotional experience with emerging findings of neuroscientific research. Consequently, an informed and clear understanding of the fundamental facets of psychoanalytic theory and orientation are essential for the student’s grasp of a large and significant segment of current psychiatric thinking.

At the same time, psychoanalysis is undergoing a creative ferment in which classical perspectives are constantly being challenged and revised, leading to a diversity of emphases and viewpoints, all of which can be regarded as representing aspects of psychoanalytic thinking. This has given rise to the question as to whether psychoanalysis is one theory or more than one. The divergence of multiple theoretical variants raises the question of the degree to which newer perspectives can be reconciled to classical perspectives.

The spirit of creative modifications in theory was inaugurated by Freud himself. Some of the theoretical modifications of the classic theory after Freud have attempted to reformulate basic analytic propositions while still retaining the spirit and fundamental insights of a Freudian perspective; others have challenged and abandoned basic analytic insights in favor of divergent paradigms that seem radically different and even contradictory to basic analytic principles.

Although there is more than one way to approach the diversity of such material, the decision has been made to organize this material along roughly historical lines, tracing the emergence of analytic theory or theories over time, but with a good deal of overlap and some redundancy. But there is an overall pattern of gradual emergence, progressing from early drive theory to structural theory to ego psychology to object relations, and on to self psychology, intersubjectivism, and relational approaches.

Psychoanalysis today is recognized as having three crucial aspects: it is a therapeutic technique, a body of scientific and theoretical knowledge, and a method of investigation. This section focuses on psychoanalysis as both a theory and a treatment, but the basic tenets elaborated here have wide applications to nonpsychoanalytic settings in clinical psychiatry.

LIFE OF FREUD

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) was born in Freiburg, a small town in Moravia, which is now part of the Czech Republic. When Freud was 4 years old, his father, a Jewish wool merchant, moved the family to Vienna, where Freud spent most of his life. Following medical school, he specialized in neurology and studied for a year in Paris with Jean-Martin Charcot. He was also influenced by Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault and Hippolyte-Marie Bernheim, both of whom taught him hypnosis while he was in France. After his education in France, he returned to Vienna and began clinical work with hysterical patients. Between 1887 and 1897, his work with these patients led him to develop psychoanalysis. Figures 4.1-1 and 4.1-2 show Freud at age 47 and 79, respectively.

FIGURE 4.1-1

Sigmund Freud at age 47. (Courtesy of Menninger Foundation Archives, Topeka, KS.)

FIGURE 4.1-2

Sigmund Freud at age 79. (Courtesy of Menninger Foundation Archives, Topeka, KS.)

BEGINNINGS OF PSYCHOANALYSIS

In the decade from 1887 to 1897, Freud immersed himself in the serious study of the disturbances in his hysterical patients, resulting in discoveries that contributed to the beginnings of psychoanalysis. These slender beginnings had a threefold aspect: Emergence of psychoanalysis as a method of investigation, as a therapeutic technique, and as a body of scientific knowledge based on an increasing fund of information and basic theoretical propositions. These early researches flowed out of Freud’s initial collaboration with Joseph Breuer and then, increasingly, from his own independent investigations and theoretical developments.

THE CASE OF ANNA O

Breuer was an older physician, a distinguished and well-established medical practitioner in the Viennese community (Fig. 4.1-3). Knowing Freud’s interests in hysterical pathology, Breuer told him about the unusual case of a woman he had treated for approximately 1.5 years, from December 1880 to June 1882. This woman became famous under the pseudonym Fräulein Anna O, and study of her difficulties proved to be one of the important stimuli in the development of psychoanalysis.

FIGURE 4.1-3

Joseph Breuer (1842–1925).

Anna O was, in reality, Bertha Pappenheim, who later became independently famous as a founder of the social work movement in Germany. At the time she began to see Breuer, she was an intelligent and strong-minded young woman of approximately 21 years of age who had developed a number of hysterical symptoms in connection with the illness and death of her father. These symptoms included paralysis of the limbs, contractures, anesthesias, visual and speech disturbances, anorexia, and a distressing nervous cough. Her illness was also characterized by two distinct phases of consciousness: One relatively normal, but the other reflected a second and more pathological personality.

Anna was very fond of and close to her father and shared with her mother the duties of nursing him on his deathbed. During her altered states of consciousness, Anna was able to recall the vivid fantasies and intense emotions she had experienced while caring for her father. It was with considerable amazement, both to Anna and Breuer, that when she was able to recall, with the associated expression of affect, the scenes or circumstances under which her symptoms had arisen, the symptoms would disappear. She vividly described this process as the “talking cure” and as “chimney sweeping.”

Once the connection between talking through the circumstances of the symptoms and the disappearance of the symptoms themselves had been established, Anna proceeded to deal with each of her many symptoms, one after another. She was able to recall that on one occasion, when her mother had been absent, she had been sitting at her father’s bedside and had had a fantasy or daydream in which she imagined that a snake was crawling toward her father and was about to bite him. She struggled forward to try to ward off the snake, but her arm, which had been draped over the back of the chair, had gone to sleep. She was unable to move it. The paralysis persisted, and she was unable to move the arm until, under hypnosis, she was able to recall this scene. It is easy to see how this kind of material must have made a profound impression on Freud. It provided convincing demonstration of the power of unconscious memories and suppressed affects in producing hysterical symptoms.

In the course of the somewhat lengthy treatment, Breuer had become increasingly preoccupied with his fascinating and unusual patient and, consequently, spent more and more time with her. Meanwhile, his wife had grown increasingly jealous and resentful. As soon as Breuer began to realize this, the sexual connotations of it frightened him, and he abruptly terminated the treatment. Only a few hours later, however, he was recalled urgently to Anna’s bedside. She had never alluded to the forbidden topic of sex during the course of her treatment, but she was now experiencing hysterical childbirth. Freud saw the phantom pregnancy as the logical outcome of the sexual feelings she had developed toward Breuer in response to his therapeutic attention. Breuer himself had been quite unaware of this development, and the experience was quite unnerving. He was able to calm Anna down by hypnotizing her, but then he left the house in a cold sweat and immediately set out with his wife for Venice on a second honeymoon.

According to a version that comes from Freud through Ernest Jones, the patient was far from cured and later had to be hospitalized after Breuer’s departure. It seems ironic that the prototype of a cathartic cure was, in fact, far from successful. Nevertheless, the case of Anna O provided an important starting point for Freud’s thinking and a crucial juncture in the development of psychoanalysis.

THE INTERPRETATION OF DREAMS

In his landmark publication The Interpretation of Dreams in 1900, Freud presented a theory of the dreaming process that paralleled his earlier analysis of psychoneurotic symptoms. He viewed the dream experience as a conscious expression of unconscious fantasies or wishes not readily acceptable to conscious waking experience. Thus, dream activity was considered to be one of the normal manifestations of unconscious processes.

The dream images represented unconscious wishes or thoughts, disguised through a process of symbolization and other distorting mechanisms. This reworking of unconscious contents constituted the dream work. Freud postulated the existence of a “censor,” pictured as guarding the border between the unconscious part of the mind and the preconscious level. The censor functioned to exclude unconscious wishes during conscious states but, during regressive relaxation of sleep, allowed certain unconscious contents to pass the border, only after transformation of these unconscious wishes into disguised forms experienced in the manifest dream contents by the sleeping subject. Freud assumed that the censor worked in the service of the ego—that is, as serving the self-preservative objectives of the ego. Although he was aware of the unconscious nature of the processes, he tended to regard the ego at this point in the development of his theory more restrictively as the source of conscious processes of reasonable control and volition.

The analysis of dreams elicits material that has been repressed. These unconscious thoughts and wishes include nocturnal sensory stimuli (sensory impressions such as pain, hunger, thirst, urinary urgency), the day residue (thoughts and ideas that are connected with the activities and preoccupations of the dreamer’s current waking life), and repressed unacceptable impulses. Because motility is blocked by the sleep state, the dream enables partial but limited gratification of the repressed impulse that gives rise to the dream.

Freud distinguished between two layers of dream content. The manifest content refers to what is recalled by the dreamer; the latent content involves the unconscious thoughts and wishes that threaten to awaken the dreamer. Freud described the unconscious mental operations by which latent dream content is transformed into manifest dream as the dream work. Repressed wishes and impulses must attach themselves to innocent or neutral images to pass the scrutiny of the dream censor. This process involves selection of apparently meaningless or trivial images from the dreamer’s current experience, images that are dynamically associated with the latent images that they resemble in some respect.

Condensation

Condensation is the mechanism by which several unconscious wishes, impulses, or attitudes can be combined into a single image in the manifest dream content. Thus, in a child’s nightmare, an attacking monster may come to represent not only the dreamer’s father but may also represent some aspects of the mother and even some of the child’s own primitive hostile impulses as well. The converse of condensation can also occur in the dream work, namely, an irradiation or diffusion of a single latent wish or impulse that is distributed through multiple representations in the manifest dream content. The combination of mechanisms of condensation and diffusion provides the dreamer with a highly flexible and economic device for facilitating, compressing, and diffusing or expanding the manifest dream content, which is derived from latent or unconscious wishes and impulses.

Displacement

The mechanism of displacement refers to the transfer of amounts of energy (cathexis) from an original object to a substitute or symbolic representation of the object. Because the substitute object is relatively neutral—that is, less invested with affective energy—it is more acceptable to the dream censor and can pass the borders of repression more easily. Thus, whereas symbolism can be taken to refer to the substitution of one object for another, displacement facilitates distortion of unconscious wishes through transfer of affective energy from one object to another. Despite the transfer of cathectic energy, the aim of the unconscious impulse remains unchanged. For example, in a dream, the mother may be represented visually by an unknown female figure (at least one who has less emotional significance for the dreamer), but the naked content of the dream nonetheless continues to derive from the dreamer’s unconscious instinctual impulses toward the mother.

Symbolic Representation

Freud noted that the dreamer would often represent highly charged ideas or objects by using innocent images that were in some way connected with the idea or object being represented. In this manner, an abstract concept or a complex set of feelings toward a person could be symbolized by a simple, concrete, or sensory image. Freud noted that symbols have unconscious meanings that can be discerned through the patient’s associations to the symbol, but he also believed that certain symbols have universal meanings.

Secondary Revision

The mechanisms of condensation, displacement, and symbolic representation are characteristic of a type of thinking that Freud referred to as primary process. This primitive mode of cognitive activity is characterized by illogical, bizarre, and absurd images that seem incoherent. Freud believed that a more mature and reasonable aspect of the ego works during dreams to organize primitive aspects of dreams into a more coherent form. Secondary revision is Freud’s name for this process, in which dreams become somewhat more rational. The process is related to mature activity characteristic of waking life, which Freud termed secondary process.

Affects in Dreams

Secondary emotions may not appear in the dream at all, or they may be experienced in somewhat altered form. For example, repressed rage toward a person’s father may take the form of mild annoyance. Feelings may also appear as their opposites.

Anxiety Dreams

Freud’s dream theory preceded his development of a comprehensive theory of the ego. Hence, his understanding of dreams stresses the importance of discharging drives or wishes through the hallucinatory contents of the dream. He viewed such mechanisms as condensation, displacement, symbolic representation, projection, and secondary revision primarily as facilitating the discharge of latent impulses, rather than as protecting dreamers from anxiety and pain. Freud understood anxiety dreams as reflecting a failure in the protective function of the dream-work mechanisms. The repressed impulses succeed in working their way into the manifest content in a more or less recognizable manner.

Punishment Dreams

Dreams in which dreamers experience punishment represented a special challenge for Freud because they appear to represent an exception to his wish fulfillment theory of dreams. He came to understand such dreams as reflecting a compromise between the repressed wish and the repressing agency or conscience. In a punishment dream, the ego anticipates condemnation on the part of the dreamer’s conscience if the latent unacceptable impulses are allowed direct expression in the manifest dream content. Hence, the wish for punishment on the part of the patient’s conscience is satisfied by giving expression to punishment fantasies.

TOPOGRAPHICAL MODEL OF THE MIND

The publication of The Interpretation of Dreams in 1900 heralded the arrival of Freud’s topographical model of the mind, in which he divided the mind into three regions: the conscious system, the preconscious system, and the unconscious system. Each system has its own unique characteristics.

The Conscious

The conscious system in Freud’s topographical model is the part of the mind in which perceptions coming from the outside world or from within the body or mind are brought into awareness. Consciousness is a subjective phenomenon whose content can be communicated only by means of language or behavior. Freud assumed that consciousness used a form of neutralized psychic energy that he referred to as attention cathexis, whereby persons were aware of a particular idea or feeling as a result of investing a discrete amount of psychic energy in the idea or feeling.

The Preconscious

The preconscious system is composed of those mental events, processes, and contents that can be brought into conscious awareness by the act of focusing attention. Although most persons are not consciously aware of the appearance of their first-grade teacher, they ordinarily can bring this image to mind by deliberately focusing attention on the memory. Conceptually, the preconscious interfaces with both unconscious and conscious regions of the mind. To reach conscious awareness, contents of the unconscious must become linked with words and thus become preconscious. The preconscious system also serves to maintain the repressive barrier and to censor unacceptable wishes and desires.

The Unconscious

The unconscious system is dynamic. Its mental contents and processes are kept from conscious awareness through the force of censorship or repression, and it is closely related to instinctual drives. At this point in Freud’s theory of development, instincts were thought to consist of sexual and self-preservative drives, and the unconscious was thought to contain primarily the mental representations and derivatives of the sexual instinct.

The content of the unconscious is limited to wishes seeking fulfillment. These wishes provide the motivation for dream and neurotic symptom formation. This view is now considered reductionist.

The unconscious system is characterized by primary process thinking, which is principally aimed at facilitating wish fulfillment and instinctual discharge. It is governed by the pleasure principle and, therefore, disregards logical connections; it has no concept of time, represents wishes as fulfillments, permits contradictions to exist simultaneously, and denies the existence of negatives. The primary process is also characterized by extreme mobility of drive cathexis; the investment of psychic energy can shift from object to object without opposition. Memories in the unconscious have been divorced from their connection with verbal symbols. Hence, when words are reapplied to forgotten memory traits, as in psychoanalytic treatment, the verbal recathexis allows the memories to reach consciousness again.

The contents of the unconscious can become conscious only by passing through the preconscious. When censors are overpowered, the elements can enter consciousness.

Limitations of the Topographical Theory

Freud soon realized that two main deficiencies in the topographical theory limited its usefulness. First, many patients’ defense mechanisms that guard against distressing wishes, feelings, or thoughts were themselves not initially accessible to consciousness. Thus, repression cannot be identical with preconscious, because by definition this region of the mind is accessible to consciousness. Second, Freud’s patients frequently demonstrated an unconscious need for punishment. This clinical observation made it unlikely that the moral agency making the demand for punishment could be allied with anti-instinctual forces that were available to conscious awareness in the preconscious. These difficulties led Freud to discard the topographical theory, but certain concepts derived from the theory continue to be useful, particularly, primary and secondary thought processes, the fundamental importance of wish fulfillment, the existence of a dynamic unconscious, and a tendency toward regression under frustrating conditions.

INSTINCT OR DRIVE THEORY

After the development of the topographical model, Freud turned his attention to the complexities of instinct theory. Freud was determined to anchor his psychological theory in biology. His choice led to terminological and conceptual difficulties when he used terms derived from biology to denote psychological constructs. Instinct, for example, refers to a pattern of species-specific behavior that is genetically derived and, therefore, is more or less independent of learning. Modern research demonstrating that instinctual patterns are modified through experiential learning, however, has made Freud’s instinctual theory problematic. Further confusion has stemmed from the ambiguity inherent in a concept on the borderland between the biological and the psychological: Should the mental representation aspect of the term and the physiological component be integrated or separated? Although drive may have been closer than instinct to Freud’s meaning, in contemporary usage, the two terms are often used interchangeably.

In Freud’s view, an instinct has four principal characteristics: source, impetus, aim, and object. The source refers to the part of the body from which the instinct arises. The impetus is the amount of force or intensity associated with the instinct. The aim refers to any action directed toward tension discharge or satisfaction, and the object is the target (often a person) for this action.

Instincts

Libido. The ambiguity in the term instinctual drive is also reflected in the use of the term libido. Briefly, Freud regarded the sexual instinct as a psychophysiological process that had both mental and physiological manifestations. Essentially, he used the term libido to refer to “the force by which the sexual instinct is represented in the mind.” Thus, in its accepted sense, libido refers specifically to the mental manifestations of the sexual instinct. Freud recognized early that the sexual instinct did not originate in a finished or final form, as represented by the stage of genital primacy. Rather, it underwent a complex process of development, at each phase of which the libido had specific aims and objects that diverged in varying degrees from the simple aim of genital union. The libido theory thus came to include all of these manifestations and the complicated paths they followed in the course of psychosexual development.

Ego Instincts. From 1905 on, Freud maintained a dual instinct theory, subsuming sexual instincts and ego instincts connected with self-preservation. Until 1914, with the publication of On Narcissism, Freud had paid little attention to ego instincts; in this communication, however, Freud invested ego instinct with libido for the first time by postulating an ego libido and an object libido. Freud thus viewed narcissistic investment as an essentially libidinal instinct and called the remaining nonsexual components the ego instincts.

Aggression. When psychoanalysts today discuss the dual instinct theory, they are generally referring to libido and aggression. Freud, however, originally conceptualized aggression as a component of the sexual instincts in the form of sadism. As he became aware that sadism had nonsexual aspects to it, he made finer gradations, which enabled him to categorize aggression and hate as part of the ego instincts and the libidinal aspects of sadism as components of the sexual instincts. Finally, in 1923, to account for the clinical data he was observing, he was compelled to conceive of aggression as a separate instinct in its own right. The source of this instinct, according to Freud, was largely in skeletal muscles, and the aim of the aggressive instincts was destruction.

Life and Death Instincts. Before designating aggression as a separate instinct, Freud, in 1920, subsumed the ego instincts under a broader category of life instincts. These were juxtaposed with death instincts and were referred to as Eros and Thanatos in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. The life and death instincts were regarded as forces underlying the sexual and aggressive instincts. Although Freud could not provide clinical data that directly verified the death instinct, he thought the instinct could be inferred by observing repetition compulsion, a person’s tendency to repeat past traumatic behavior. Freud thought that the dominant force in biological organisms had to be the death instinct. In contrast to the death instinct, eros (the life instinct) refers to the tendency of particles to reunite or bind to one another, as in sexual reproduction. The prevalent view today is that the dual instincts of sexuality and aggression suffice to explain most clinical phenomena without recourse to a death instinct.

Pleasure and Reality Principles

In 1911, Freud described two basic tenets of mental functioning: the pleasure principle and the reality principle. He essentially recast the primary process and secondary process dichotomy into the pleasure and reality principles and thus took an important step toward solidifying the notion of the ego. Both principles, in Freud’s view, are aspects of ego functioning. The pleasure principle is defined as an inborn tendency of the organism to avoid pain and to seek pleasure through the discharge of tension. The reality principle, on the other hand, is considered to be a learned function closely related to the maturation of the ego; this principle modifies the pleasure principle and requires delay or postponement of immediate gratification.

Infantile Sexuality

Freud set forth the three major tenets of psychoanalytic theory when he published Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. First, he broadened the definition of sexuality to include forms of pleasure that transcend genital sexuality. Second, he established a developmental theory of childhood sexuality that delineated the vicissitudes of erotic activity from birth through puberty. Third, he forged a conceptual linkage between neuroses and perversions.

Freud’s notion that children are influenced by sexual drives has made some persons reluctant to accept psychoanalysis. Freud noted that infants are capable of erotic activity from birth, but the earliest manifestations of infantile sexuality are basically nonsexual and are associated with such bodily functions as feeding and bowel–bladder control. As libidinal energy shifts from the oral zone to the anal zone to the phallic zone, each stage of development is thought to build on and to subsume the accomplishments of the preceding stage. The oral stage, which occupies the first 12 to 18 months of life, centers on the mouth and lips and is manifested in chewing, biting, and sucking. The dominant erotic activity of the anal stage, from 18 to 36 months of age, involves bowel function and control. The phallic stage, from 3 to 5 years of life, initially focuses on urination as the source of erotic activity. Freud suggested that phallic erotic activity in boys is a preliminary stage leading to adult genital activity. Whereas the penis remains the principal sexual organ throughout male psychosexual development, Freud postulated that females have two principal erotogenic zones: the vagina and the clitoris. He thought that the clitoris was the chief erotogenic focus during the infantile genital period but that erotic primacy shifted to the vagina after puberty. Studies of human sexuality have subsequently questioned the validity of this distinction.

Freud discovered that in the psychoneuroses, only a limited number of the sexual impulses that had undergone repression and were responsible for creating and maintaining the neurotic symptoms were normal. For the most part, these were the same impulses that were given overt expression in the perversions. The neuroses, then, were the negative of perversions.

Object Relationships in Instinct Theory

Freud suggested that the choice of a love object in adult life, the love relationship itself, and the nature of all other object relationships depend primarily on the nature and quality of children’s relationships during the early years of life. In describing the libidinal phases of psychosexual development, Freud repeatedly referred to the significance of a child’s relationships with parents and other significant persons in the environment.

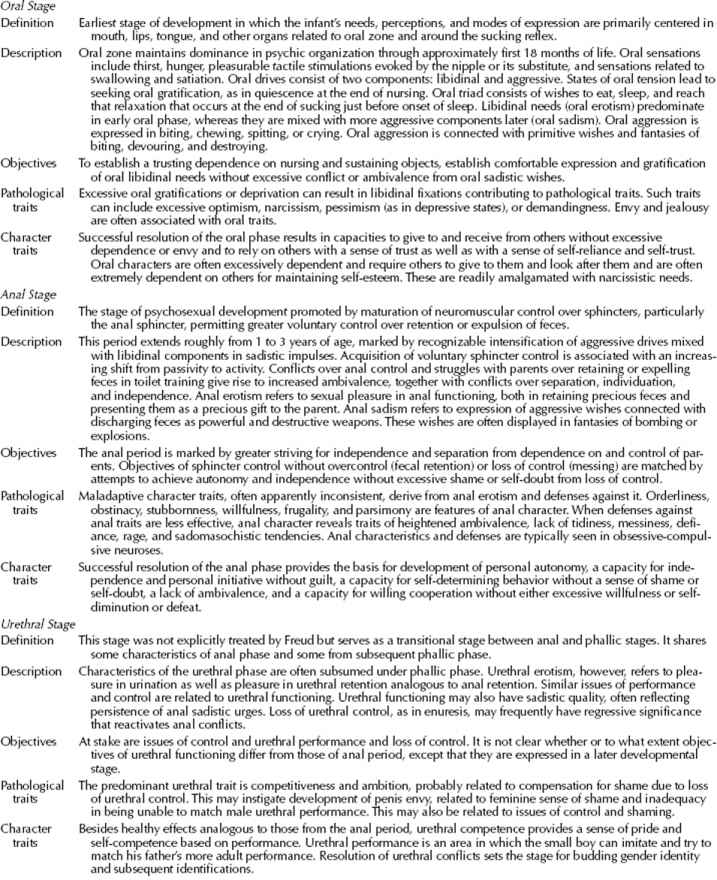

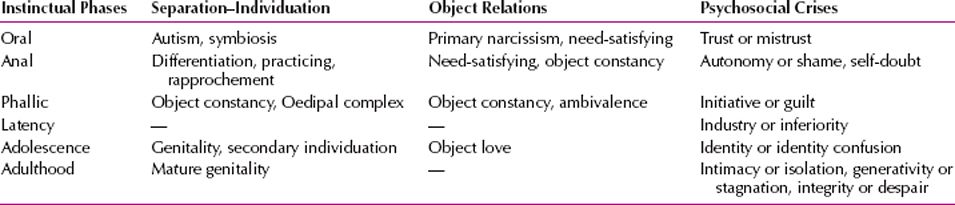

The awareness of the external world of objects develops gradually in infants. Soon after birth, they are primarily aware of physical sensations, such as hunger, cold, and pain, which give rise to tension, and caregivers are regarded primarily as persons who relieve their tension or remove painful stimuli. Recent infant research, however, suggests that awareness of others begins much sooner than Freud originally thought. Table 4.1-1 provides a summary of the stages of psychosexual development and the object relationships associated with each stage. Although the table goes only as far as young adulthood, development is now recognized as continuing throughout adult life.

Table 4.1-1

Table 4.1-1

Stages of Psychosexual Development

Concept of Narcissism

According to Greek myth, Narcissus, a beautiful youth, fell in love with his reflection in the water of a pool and drowned in his attempt to embrace his beloved image. Freud used the term narcissism to describe situations in which an individual’s libido was invested in the ego itself rather than in other persons. This concept of narcissism presented him with vexing problems for his instinct theory and essentially violated his distinction between libidinal instincts and ego or self-preservative instincts. Freud’s understanding of narcissism led him to use the term to describe a wide array of psychiatric disorders, very much in contrast to the term’s contemporary use to describe a specific personality disorder. Freud grouped several disorders together as the narcissistic neuroses, in which a person’s libido is withdrawn from objects and turned inward. He believed that this withdrawal of libidinal attachment to objects accounted for the loss of reality testing in patients who were psychotic; grandiosity and omnipotence in such patients reflected excessive libidinal investment in the ego.

Freud did not limit his use of narcissism to psychoses. In states of physical illness and hypochondriasis, he observed that libidinal investment was frequently withdrawn from external objects and from outside activities and interests. Similarly, he suggested that in normal sleep, libido was also withdrawn and reinvested in a sleeper’s own body. Freud regarded homosexuality as an instance of a narcissistic form of object choice, in which persons fall in love with an idealized version of themselves projected onto another person. He also found narcissistic manifestations in the beliefs and myths of primitive people, especially those involving the ability to influence external events through the magical omnipotence of thought processes. In the course of normal development, children also exhibit this belief in their own omnipotence.

Freud postulated a state of primary narcissism at birth in which the libido is stored in the ego. He viewed the neonate as completely narcissistic, with the entire libidinal investment in physiological needs and their satisfaction. He referred to this self-investment as ego libido. The infantile state of self-absorption changes only gradually, according to Freud, with the dawning awareness that a separate person—the mothering figure—is responsible for gratifying an infant’s needs. This realization leads to the gradual withdrawal of the libido from the self and its redirection toward the external object. Hence, the development of object relations in infants parallels the shift from primary narcissism to object attachment. The libidinal investment in the object is referred to as object libido. If a developing child suffers rebuffs or trauma from the caretaking figure, object libido may be withdrawn and reinvested in the ego. Freud called this regressive posture secondary narcissism.

Freud used the term narcissism to describe many different dimensions of human experience. At times, he used it to describe a perversion in which persons used their own bodies or body parts as objects of sexual arousal. At other times, he used the term to describe a developmental phase, as in the state of primary narcissism. In still other instances, the term referred to a particular object choice. Freud distinguished love objects who are chosen “according to the narcissistic type,” in which case the object resembles the subject’s idealized or fantasied self-image, from objects chosen according to the “anaclitic,” in which the love object resembles a caretaker from early in life. Finally, Freud also used the word narcissism interchangeably and synonymously with self-esteem.

EGO PSYCHOLOGY

Although Freud had used the construct of the ego throughout the evolution of psychoanalytic theory, ego psychology as it is known today really began with the publication in 1923 of The Ego and the Id. This landmark publication also represented a transition in Freud’s thinking from the topographical model of the mind to the tripartite structural model of ego, id, and superego. He had observed repeatedly that not all unconscious processes can be relegated to a person’s instinctual life. Elements of the conscience, as well as functions of the ego, are clearly also unconscious.

Structural Theory of the Mind

The structural model of the psychic apparatus is the cornerstone of ego psychology. The three provinces—id, ego, and superego—are distinguished by their different functions.

Id. Freud used the term id to refer to a reservoir of unorganized instinctual drives. Operating under the domination of the primary process, the id lacks the capacity to delay or modify the instinctual drives with which an infant is born. The id, however, should not be viewed as synonymous with the unconscious, because both the ego and the superego have unconscious components.

Ego. The ego spans all three topographical dimensions of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious. Logical and abstract thinking and verbal expression are associated with conscious and preconscious functions of the ego. Defense mechanisms reside in the unconscious domain of the ego. The ego, the executive organ of the psyche, controls motility, perception, contact with reality, and, through the defense mechanisms available to it, the delay and modulation of drive expression.

Freud believed that the id is modified as a result of the impact of the external world on the drives. The pressures of external reality enable the ego to appropriate the energies of the id to do its work. As the ego brings influences from the external world to bear on the id, it simultaneously substitutes the reality principle for the pleasure principle. Freud emphasized the role of conflict within the structural model and observed that conflict occurs initially between the id and the outside world, only to be transformed later to conflict between the id and the ego.

The third component of the tripartite structural model is the superego. The superego establishes and maintains an individual’s moral conscience on the basis of a complex system of ideals and values internalized from parents. Freud viewed the superego as the heir to the Oedipus complex. Children internalize parental values and standards at about the age of 5 or 6 years. The superego then serves as an agency that provides ongoing scrutiny of a person’s behavior, thoughts, and feelings; it makes comparisons with expected standards of behavior and offers approval or disapproval. These activities occur largely unconsciously.

The ego ideal is often regarded as a component of the superego. It is an agency that prescribes what a person should do according to internalized standards and values. The superego, by contrast, is an agency of moral conscience that proscribes—that is, dictates what a person should not do. Throughout the latency period and thereafter, persons continue to build on early identifications through their contact with admired figures who contribute to the formation of moral standards, aspirations, and ideals.

Functions of the Ego

Modern ego psychologists have identified a set of basic ego functions that characterizes the operations of the ego. These descriptions reflect the ego activities that are generally regarded as fundamental.

Control and Regulation of Instinctual Drives. The development of the capacity to delay or postpone drive discharge, like the capacity to test reality, is closely related to the early childhood progression from the pleasure principle to the reality principle. This capacity is also an essential aspect of the ego’s role as mediator between the id and the outside world. Part of infants’ socialization to the external world is the acquisition of language and secondary process or logical thinking.

Judgment. A closely related ego function is judgment, which involves the ability to anticipate the consequences of actions. As with control and regulation of instinctual drives, judgment develops in parallel with the growth of secondary process thinking. The ability to think logically allows assessment of how contemplated behavior may affect others.

Relation to Reality. The mediation between the internal world and external reality is a crucial function of the ego. Relations with the outside world can be divided into three aspects: the sense of reality, reality testing, and adaptation to reality. The sense of reality develops in concert with an infant’s dawning awareness of bodily sensations. The ability to distinguish what is outside the body from what is inside is an essential aspect of the sense of reality, and disturbances of body boundaries, such as depersonalization, reflect impairment in this ego function. Reality testing, an ego function of paramount importance, refers to the capacity to distinguish internal fantasy from external reality. This function differentiates persons who are psychotic from those who are not. Adaptation to reality involves persons’ ability to use their resources to develop effective responses to changing circumstances on the basis of previous experience with reality.

Object Relationships. The capacity to form mutually satisfying relationships is related in part to patterns of internalization stemming from early interactions with parents and other significant figures. This ability is also a fundamental function of the ego, in that satisfying relatedness depends on the ability to integrate positive and negative aspects of others and self and to maintain an internal sense of others even in their absence. Similarly, mastery of drive derivatives is also crucial to the achievement of satisfying relationships. Although Freud did not develop an extensive object relations theory, British psychoanalysts, such as Ronald Fairbairn (1889–1964) and Michael Balint (1896–1970), elaborated greatly on the early stages in infants’ relationships with need-satisfying objects and on the gradual development of a sense of separateness from the mother. Another of their British colleagues, Donald W. Winnicott (1896–1971), described the transitional object (e.g., a blanket, teddy bear, or pacifier) as the link between developing children and their mothers. A child can separate from the mother because a transitional object provides feelings of security in her absence. The stages of human development and object relations theory are summarized in Table 4.1-2.

Table 4.1-2

Table 4.1-2

Parallel Lines of Development

Synthetic Function of the Ego. First described by Herman Nunberg in 1931, the synthetic function refers to the ego’s capacity to integrate diverse elements into an overall unity. Different aspects of self and others, for example, are synthesized into a consistent representation that endures over time. The function also involves organizing, coordinating, and generalizing or simplifying large amounts of data.

Primary Autonomous Ego Functions. Heinz Hartmann described the so-called primary autonomous functions of the ego as rudimentary apparatuses present at birth that develop independently of intrapsychic conflict between drives and defenses. These functions include perception, learning, intelligence, intuition, language, thinking, comprehension, and motility. In the course of development, some of these conflict-free aspects of the ego may eventually become involved in conflict. They will develop normally if the infant is raised in what Hartmann referred to as an average expectable environment.

Secondary Autonomous Ego Functions. Once the sphere where primary autonomous function develops becomes involved with conflict, so-called secondary autonomous ego functions arise in the defense against drives. For example, a child may develop caretaking functions as a reaction formation against murderous wishes during the first few years of life. Later, the defensive functions may be neutralized or deinstinctualized when the child grows up to be a social worker and cares for homeless persons.

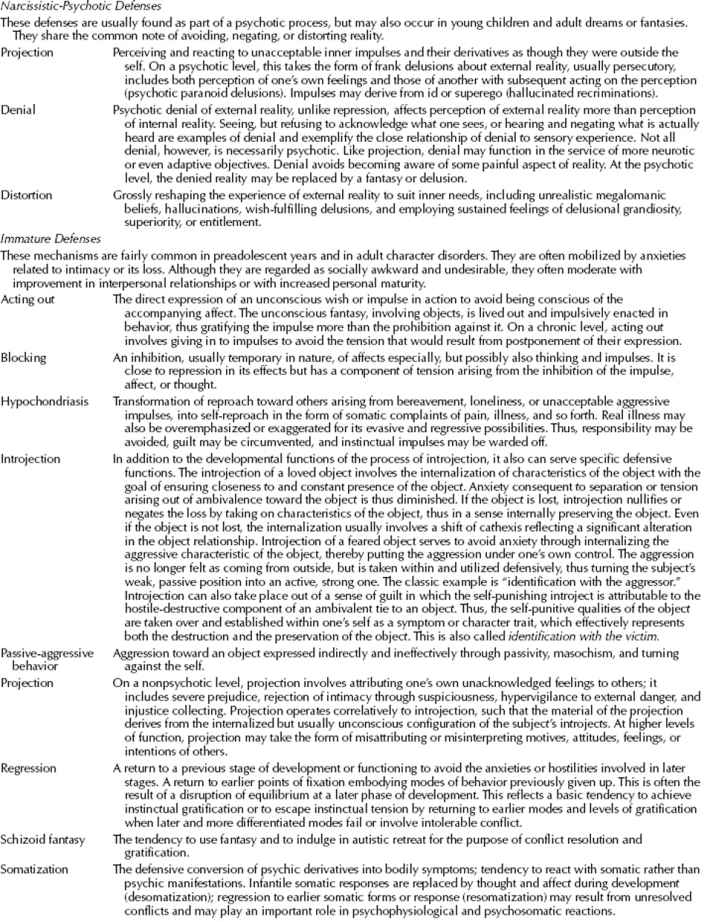

Defense Mechanisms

At each phase of libidinal development, specific drive components evoke characteristic ego defenses. The anal phase, for example, is associated with reaction formation, as manifested by the development of shame and disgust in relation to anal impulses and pleasures.

Defenses can be grouped hierarchically according to the relative degree of maturity associated with them. Narcissistic defenses are the most primitive and appear in children and persons who are psychotically disturbed. Immature defenses are seen in adolescents and some nonpsychotic patients. Neurotic defenses are encountered in obsessive-compulsive and hysterical patients as well as in adults under stress. Table 4.1-3 lists the defense mechanisms according to George Valliant’s classification of the four types.

Table 4.1-3

Table 4.1-3

Classification of Defense Mechanisms

Theory of Anxiety

Freud initially conceptualized anxiety as “dammed up libido.” Essentially, a physiological increase in sexual tension leads to a corresponding increase in libido, the mental representation of the physiological event. The actual neuroses are caused by this buildup. Later, with the development of the structural model, Freud developed a new theory of a second type of anxiety that he referred to as signal anxiety. In this model, anxiety operates at an unconscious level and serves to mobilize the ego’s resources to avert danger. Either external or internal sources of danger can produce a signal that leads the ego to marshal specific defense mechanisms to guard against, or reduce, instinctual excitation.

Freud’s later theory of anxiety explains neurotic symptoms as the ego’s partial failure to cope with distressing stimuli. The drive derivatives associated with danger may not have been adequately contained by the defense mechanisms used by the ego. In phobias, for example, Freud explained that fear of an external threat (e.g., dogs or snakes) is an externalization of an internal danger.

Danger situations can also be linked to developmental stages and, thus, can create a developmental hierarchy of anxiety. The earliest danger situation is a fear of disintegration or annihilation, often associated with concerns about fusion with an external object. As infants mature and recognize the mothering figure as a separate person, separation anxiety, or fear of the loss of an object, becomes more prominent. During the oedipal psychosexual stage, girls are most concerned about losing the love of the most important figure in their lives, their mother. Boys are primarily anxious about bodily injury or castration. After resolution of the oedipal conflict, a more mature form of anxiety occurs, often termed superego anxiety. This latency-age concern involves the fear that internalized parental representations, contained in the superego, will cease to love, or will angrily punish, the child.

Character

In 1913, Freud distinguished between neurotic symptoms and personality or character traits. Neurotic symptoms develop as a result of the failure of repression; character traits owe their existence to the success of repression, that is, to the defense system that achieves its aim through a persistent pattern of reaction formation and sublimation. In 1923, Freud also observed that the ego can only give up important objects by identifying with them or introjecting them. This accumulated pattern of identifications and introjections also contributes to character formation. Freud specifically emphasized the importance of superego formation in the character construction.

Contemporary psychoanalysts regard character as a person’s habitual or typical pattern of adaptation to internal drive forces and to external environmental forces. Character and personality are used interchangeably and are distinguished from the ego in that they largely refer to styles of defense and of directly observable behavior rather than to feeling and thinking.

Character is also influenced by constitutional temperament; the interaction of drive forces with early ego defenses and with environmental influences; and various identifications with, and internalizations of, other persons throughout life. The extent to which the ego has developed a capacity to tolerate the delay of impulse discharge and to neutralize instinctual energy determines the degree to which such character traits emerge in later life. Exaggerated development of certain character traits at the expense of others can lead to personality disorders or produce a vulnerability or predisposition to psychosis.

CLASSIC PSYCHOANALYTIC THEORY OF NEUROSES

The classic view of the genesis of neuroses regards conflict as essential. The conflict can arise between instinctual drives and external reality or between internal agencies, such as the id and the superego or the id and the ego. Moreover, because the conflict has not been worked through to a realistic solution, the drives or wishes that seek discharge have been expelled from consciousness through repression or another defense mechanism. Their expulsion from conscious awareness, however, does not make the drives any less powerful or influential. As a result, the unconscious tendencies (e.g., the disguised neurotic symptoms) fight their way back into consciousness. This theory of the development of neurosis assumes that a rudimentary neurosis based on the same type of conflict existed in early childhood.

Deprivation during the first few months of life because of absent or impaired caretaking figures can adversely affect ego development. This impairment, in turn, can result in failure to make appropriate identifications. The resulting ego difficulties create problems in mediating between the drives and the environment. Lack of capacity for constructive expression of drives, especially aggression, can lead some children to turn their aggression on themselves and become overtly self-destructive. Parents who are inconsistent, excessively harsh, or overly indulgent can influence children to develop disordered superego functioning. Severe conflict that cannot be managed through symptom formation can lead to extreme restrictions in ego functioning and fundamentally impair the capacity to learn and develop new skills.

Traumatic events that seem to threaten survival can break through defenses when the ego has been weakened. More libidinal energy is then required to master the excitation that results. The libido thus mobilized, however, is withdrawn from the supply that is normally applied to external objects. This withdrawal further diminishes the strength of the ego and produces a sense of inadequacy. Frustrations or disappointments in adults may revive infantile longings that are then dealt with through symptom formation or further regression.

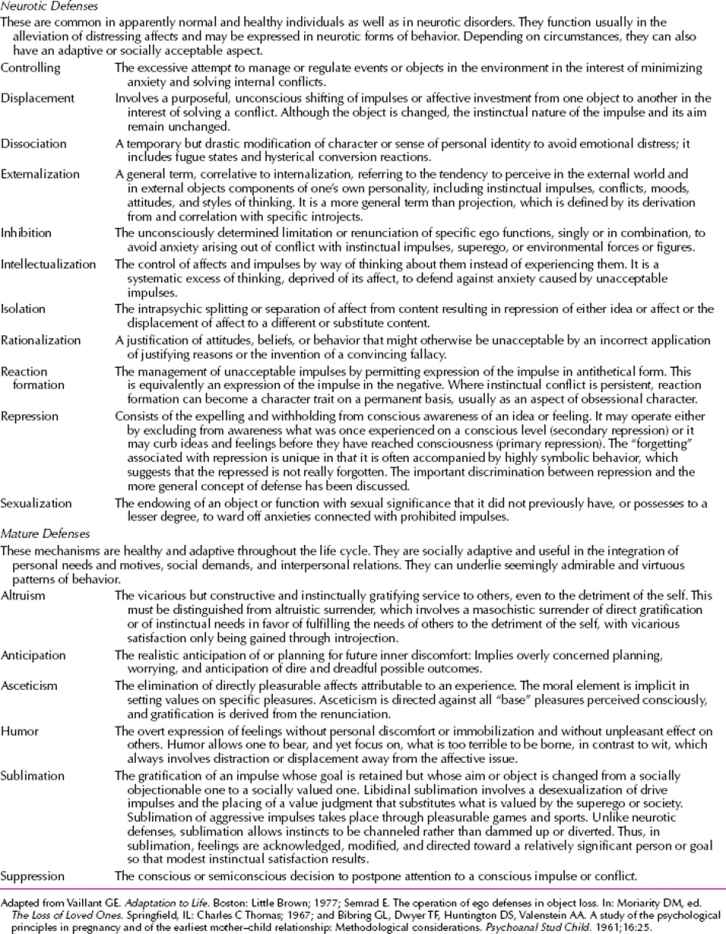

In his classic studies, Freud described four different types of childhood neuroses, three of which had later neurotic developments in adult life. This well-known series of cases shown in tabulated form in Table 4.1-4 exemplifies some of Freud’s important conclusions: (1) neurotic reactions in the adult are associated frequently with neurotic reactions in childhood; (2) the connection is sometimes continuous but more often is separated by a latent period of nonneurosis; and (3) infantile sexuality, both fantasized and real, occupies a memorable place in the early history of the patient.

Table 4.1-4

Table 4.1-4

Classic Psychoneurotic Reactions of Childhood

Certain differences are worth noting in the four cases shown in Table 4.1-4. First, the phobic reactions tend to start at about 4 or 5 years of age, the obsessional reactions between 6 and 7 years, and the conversion reactions at 8 years. The degree of background disturbance is greatest in the conversion reaction and the mixed neurosis, and it seems only slight in the phobic and obsessional reactions. The course of the phobic reaction seems little influenced by severe traumatic factors, whereas traumatic factors, such as sexual seductions, play an important role in the three other subgroups. It was during this period that Freud elaborated his seduction hypothesis for the cause of the neuroses, in terms of which the obsessive-compulsive and hysterical reactions were alleged to originate in active and passive sexual experiences.

TREATMENT AND TECHNIQUE

The cornerstone of psychoanalytic technique is free association, in which patients say whatever comes to mind. Free association does more than provide content for the analysis: It also induces the necessary regression and dependency connected with establishing and working through the transference neurosis. When this development occurs, all the original wishes, drives, and defenses associated with the infantile neurosis are transferred to the person of the analyst.

As patients attempt to free associate, they soon learn that they have difficulty saying whatever comes to mind, without censoring certain thoughts. They develop conflicts about their wishes and feelings toward the analyst that reflect childhood conflicts. The transference that develops toward the analyst may also serve as resistance to the process of free association. Freud discovered that resistance was not simply a stoppage of a patient’s associations, but also an important revelation of the patient’s internal object relations as they were externalized and manifested in the transference relationship with the analyst. The systematic analysis of transference and resistance is the essence of psychoanalysis. Freud was also aware that the analyst might have transferences to the patient, which he called countertransference. Countertransference, in Freud’s view, was an obstacle that the analyst needed to understand so that it did not interfere with treatment. In this spirit, he recognized the need for all analysts to have been analyzed themselves. Variations in transference and their descriptions are contained in Table 4.1-5. The basic mechanisms by which transferences are effected—displacement, projection, and projective identification—are described in Table 4.1-6.

Table 4.1-5

Table 4.1-5

Transference Variants

Table 4.1-6

Table 4.1-6

Transference Mechanisms

Analysts after Freud began to recognize that countertransference was not only an obstacle but also a source of useful information about the patient. In other words, the analyst’s feelings in response to the patient reflect how other persons respond to the patient and provide some indication of the patient’s own internal object relations. By understanding the intense feelings that occur in the analytic relationship, the analyst can help the patient broaden understanding of past and current relationships outside the analysis. The development of insight into neurotic conflicts also expands the ego and provides an increased sense of mastery.

REFERENCES

Bergmann MS. The Oedipus complex and psychoanalytical technique. Psychoanalytical Inquir. 2010;30(6):535.

Breger L. A Dream of Undying Fame: How Freud Betrayed His Mentor and Invented Psychoanalysis. New York: Basic Books; 2009.

Britzman DP. Freud and Education. New York: Routledge; 2011.

Cotti P. Sexuality and psychoanalytic aggrandisement: Freud’s 1908 theory of cultural history. Hist Psychiatry. 2011;22:58.

Cotti P. Travelling the path from fantasy to history: The struggle for original history within Freud’s early circle, 1908–1913. Psychoanalysis Hist. 2010;12:153.

Freud S. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. 24 vols. London: Hogarth Press; 1953–1974.

Gardner H. Sigmund Freud: Alone in the world. In: Creating Minds: An Anatomy of Creativity Seen Through the Lives of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, Stravinsky, Eliot, Graham, and Ghandi. New York: Basic Books; 2011:47.

Hoffman L. One hundred years after Sigmund Freud’s lectures in America: Towards an integration of psychoanalytic theories and techniques within psychiatry. Histor Psychiat. 2010;21(4):455.

Hollon SD, Wilson GT. Psychoanalysis or cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa: the specificity of psychological treatments. Am J Psychiatry . 2014;171:13–16.

Meissner WW. Classical psychoanalysis. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:788.

Meissner WW. The God in psychoanalysis. Psychoanal Psychol. 2009;26(2):210.

Neukrug ES. Psychoanalysis. In: Neukrug ES, ed. Counseling Theory and Practice. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole; 2011:31.

Perlman FT, Brandell JR. Psychoanalytic theory. In: Brandell JR, ed. Theory & Practice in Clinical Social Work. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011:41.

Tauber AI. Freud, the Reluctant Philosopher. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2010.

Thurschwell P. Sigmund Freud. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2009.

4.2 Erik H. Erikson

4.2 Erik H. Erikson

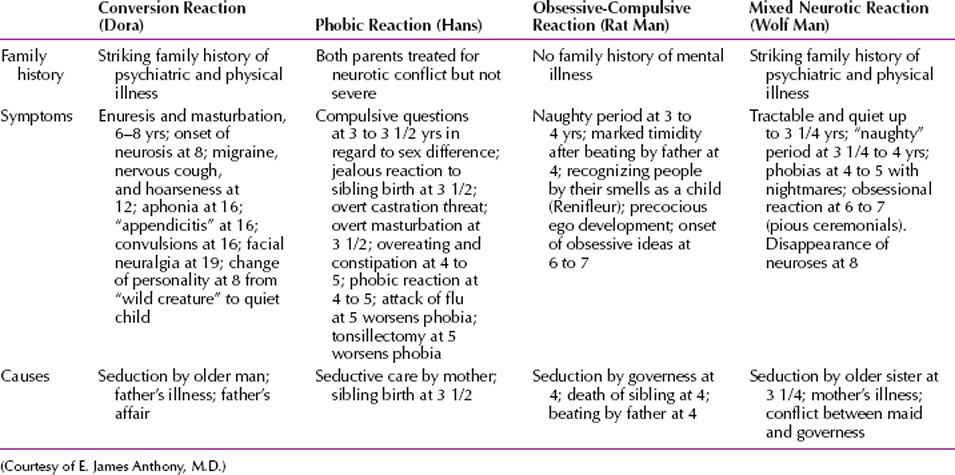

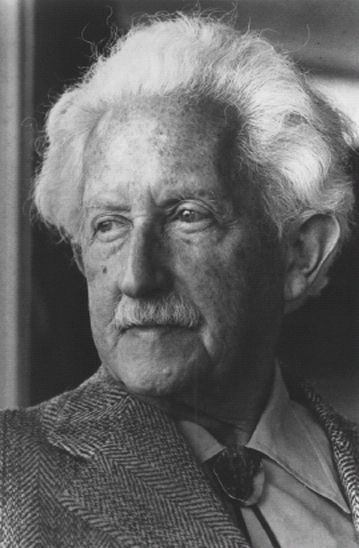

Erik H. Erikson (Fig 4.2-1) was one of America’s most influential psychoanalysts. Throughout six decades in the United States, he distinguished himself as an illuminator and expositor of Freud’s theories and as a brilliant clinician, teacher, and pioneer in psychohistorical investigation. Erikson created an original and highly influential theory of psychological development and crisis occurring in periods that extended across the entire life cycle. His theory grew out of his work first as a teacher, then as a child psychoanalyst, next as an anthropological field worker, and, finally, as a biographer. Erikson identified dilemmas or polarities in the ego’s relations with the family and larger social institutions at nodal points in childhood, adolescence, and early, middle, and late adulthood. Two of his psychosexual historical studies, Young Man Luther and Gandhi’s Truth (published in 1958 and 1969 respectively), were widely hailed as profound explorations of how crucial circumstances can interact with the crises of certain great persons at certain moments in time. The interrelationships of the psychological development of the person and the historical developments of the times were more fully explored in Life History and the Historical Moment, written by Erikson in 1975.

FIGURE 4.2-1

Erik Erikson (1902-1994).

Erik Homburger Erikson was born June 15, 1902 in Frankfurt, Germany, the son of Danish parents. He died in 1994. His father abandoned his mother before he was born, and he was brought up by his mother, a Danish Jew, and her second husband, Theordor Homburger, a German-Jewish pediatrician. Erikson’s parents chose to keep his real parentage a secret from him, and for many years he was known as Erik Homburger. Erikson never knew the identity of his biological father; his mother withheld that information from him all her life. The man who introduced the term “identity crisis” into the language undoubtedly struggled with his own sense of identity. Compounding his parents’ deception about his biological father—their “loving deceit,” as he called it—was the fact that, as a blond, blue-eyed, Scandinavian-looking son of a Jewish father, he was taunted as a “goy” among Jews, at the same time being called a Jew by his classmates. His being a Dane living in Germany added to his identity confusion. Erikson was later to describe himself as a man of the borders. Much of what he was to study was concerned with how group values are implanted in the very young, how young people grasp onto group identity in the limbo period between childhood and adulthood, and how a few persons, like Gandhi, transcend their local, national, and even temporal identities to form a small band of people with wider sympathies who span the ages.

The concepts of identity, identity crisis, and identity confusion are central to Erikson’s thought. In his first book Childhood and Society (published in 1950) Erikson observed that “the study of identity…becomes as strategic in our time as the study of sexuality was in Freud’s time.” By identity, Erikson meant a sense of sameness and continuity “in the inner core of the individual” that was maintained amid external change. A sense of identity, emerging at the end of adolescence, is a psychosocial phenomenon preceded in one form or another by an identity crisis; that crisis may be conscious or unconscious, with the person being aware of the present state and future directions but also unconscious of the basic dynamics and conflicts that underlie those states. The identity crisis can be acute and prolonged in some people.

The young Erikson did not distinguish himself in school, although he did show artistic talent. On graduation, he chose to spend a year traveling through the Black Forest, Italy, and the Alps, pondering life, drawing, and making notes. After that year of roaming, he studied art in his home city of Karlruhe and later in Munich and Florence.

In 1927 Peter Blos, a high school friend, invited Erikson to join him in Vienna. Blos, not yet a psychoanalyst, had met Dorothy Burlingham, a New Yorker who had come to Vienna to be psychoanalyzed; she had brought her four children with her and hired Blos to tutor them. Blos was looking for a fellow teacher in his new school for the children of English and American parents and students of his new discipline of psychoanalysis. Erikson accepted his offer.

Blos and Erikson organized their school in an informal manner—much in the style of the so-called progressive or experimental schools popular in the United States. Children were encouraged to participate in curriculum planning and to express themselves freely. Erikson, still very much the artist, taught drawing and painting, but he also exposed his pupils to history and to foreign ways of life, including the cultures of the American Indian and Eskimo.

During that period Erikson became involved with the Freud family, friends of Mrs. Burlingham. He became particularly close to Anna Freud, with whom he began psychoanalysis. Anna Freud, who had been an elementary school teacher, was at that time formulating the new science of child psychiatry, trying to turn attention from the adult’s corrective backward look to a neurosis-preventative study of childhood itself. Under Anna Freud’s tutelage Erikson began more and more to turn his attention to childhood, both his own and that of the children whom he saw in the classroom. Analysis was not then the rigidly structured procedure into which it later developed; Erikson met with Miss Freud daily for his analytic hour and frequently saw her socially as well, as part of the circle of Freud’s followers and associates. Still undecided about his future, Erikson continued to teach school, at the same time studying psychoanalysis at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. He also studied to become accredited as a Montessori teacher.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree