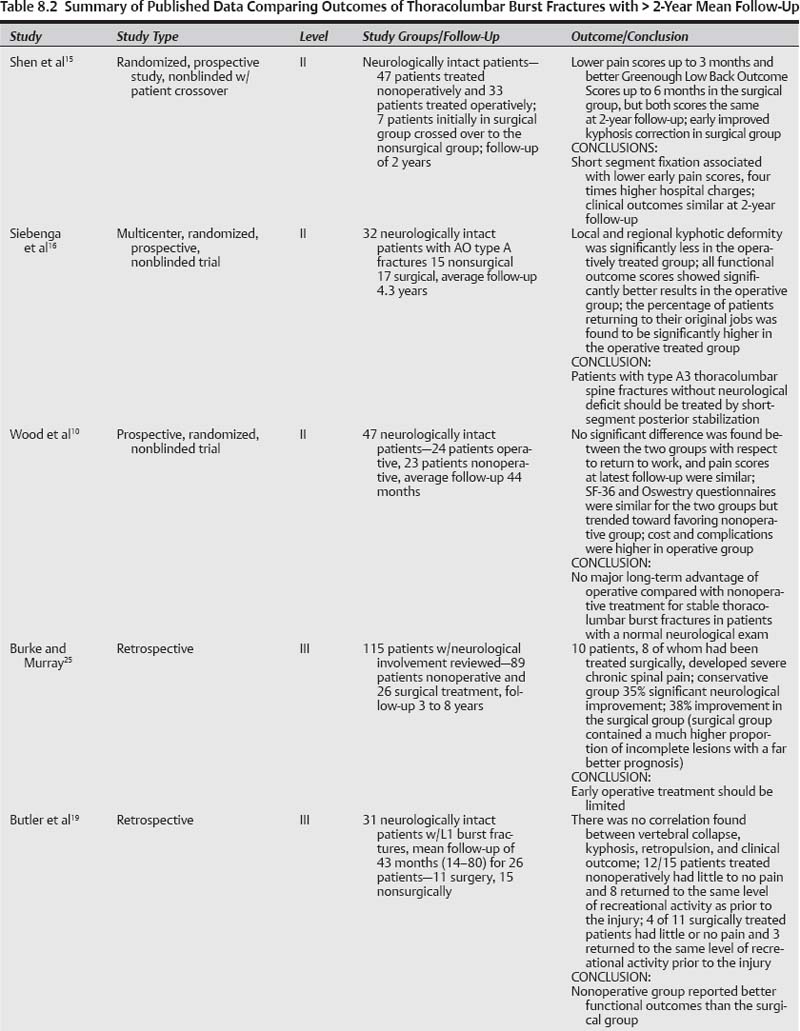

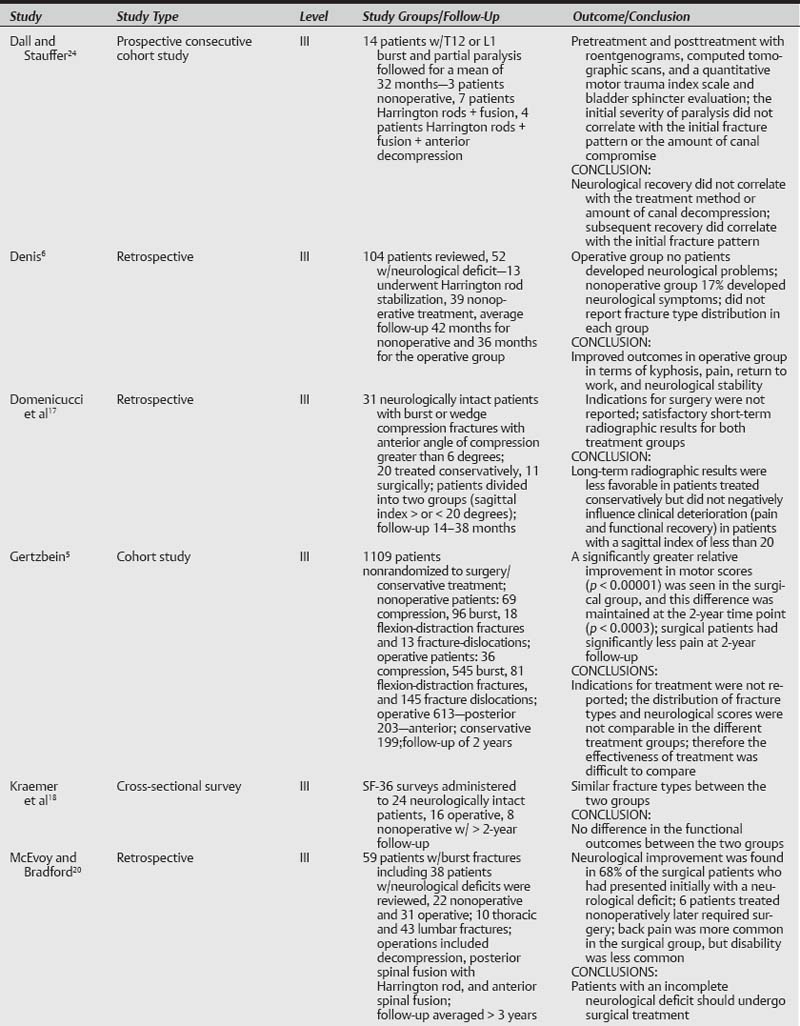

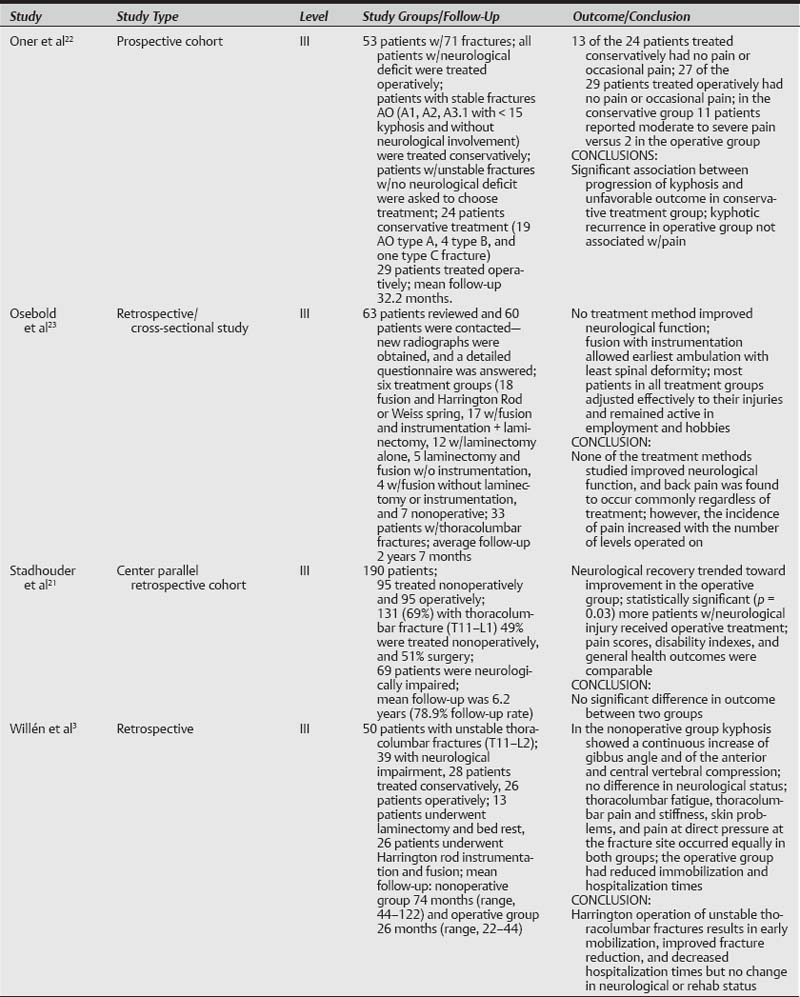

8 The thoracolumbar junction (T10–L2) is a common site of spinal injury occurring in an estimated 6% of patients experiencing blunt trauma.1 In this region, the rigid, kyphotic thoracic spine joins the more mobile, lordotic lumbar spine. The biomechanics of this junction make it particularly susceptible to injury. Burst fractures of the spine result primarily from failure of the vertebral body under axial compression. Typically, varying amounts of bone are retropulsed into the spinal canal, and the fractured body can have widely varied degrees of comminution. In making treatment decisions, the surgeon must take into account the resultant stability of the fracture and attempt to predict whether future mechanical failure will occur under physiological loads. Conservative management of burst fractures has traditionally been through bed rest and/or by fitting in a cast or brace.2,3 Surgical treatment usually involves stabilization of the injured motion segment (s) and possible decompression of the neural elements.4,5 The optimal management of thoracolumbar burst fractures continues to be one of the most controversial topics in all of spinal trauma. Diversity of the trauma patient population, heterogeneity of fracture morphology, and varying degrees of neurological injury make comparison of treatment outcomes challenging. Our goal was to review the available evidence-based literature to determine if a consensus could be reached as to whether operative or nonoperative care was best for these fractures. We subdivided our analysis of those fractures with or without neurological injury and then, again, as to whether one treatment was superior to the other if the fracture was biomechanically unstable or not. Two of the predominant classification systems for the characterization of injuries of the thoracolumbar spine that have been utilized are the Denis classification6 and the AO classification.7 In the Denis classification system, injuries are classified into four different types: compression fractures, burst fractures, seat-belt-type injuries, and fracture dislocations.6 In 1994, a comprehensive classification system of thoracolumbar burst fractures was introduced by Magerl et al.7Derived from a 10-year review of 1445 thoracolumbar injuries, the AO system is based on a hierarchical scale of increasing anatomical damage and morbidity. The three main types described in this system are type A (compression), type B (distraction), and type C (fracture-dislocation) injuries. Each of those three main types is further subdivided into three subgroups (1 through 3), and each of these is again divided into three subdivisions (e.g., A.1.1, A1.2, A1.3, A2.1, etc.). The most recent attempt to classify thoracolumbar fractures is the Thoracolumbar Injury Severity Score/Thoracolumbar Injury Classification and Severity Score (TLISS/TLICS) system.8 This scoring system is useful in making determinations about the stability of a fracture, and it considers both the neurological status of the patient and the integrity of the posterior osteoligamentous complex. The system is also useful in guiding treatment decisions and even surgical approaches. A comprehensive review of the literature was performed to access the published data on this topic. The search utilized the Medline database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) for terms “thoracic and lumbar fracture” limited to English language studies using human subjects. The initial search returned 1776 articles published between July 1964 and May 2009. These articles were screened by two independent reviewers for clinical studies related to trauma to the thoracolumbar junction with a minimum average follow-up of 2 years. These articles were graded independently according to the level of evidence ratings of Wright et al.9 In the event that there was a disparity between the gradings of the two independent reviewers (WL and DL), the senior author (KBW) entered a grade to resolve the conflict. The majority of these studies were level IV studies such as case series, case reports, biomechanical studies, and review articles, which were not included. A summary of the results of the literature review and level of evidence gradings are shown in Tables 8.1 and 8.2.

Thoracolumbar Burst Fracture: Surgery versus Conservative Care

Methods

Methods

Level | Number of Studies | Study Type |

|---|---|---|

I | 0 | No well-conducted level I studies |

II | 3 | – Single-center randomized, controlled trial nonblinded (2 studies) – Multicenter prospective randomized, nonblinded (1 study) |

III | 12 | – Retrospective (6 studies) – Prospective cohort study (4 studies) – Retrospective/cross-sectional study (1 study) – Cross-sectional survey (1 study) |

Thoracolumbar Burst Fractures in the Neurologically Intact Patient

Thoracolumbar Burst Fractures in the Neurologically Intact Patient

Level I Data

There are no level I data directly comparing long-term outcomes of operative and nonoperative treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures without a neurological deficit.

Level II Data

Three studies were reviewed representing level II data.

One prospective study of neurologically intact patients with stable thoracolumbar junction (T10–L2) burst fractures randomized 53 patients into operative and nonoperative groups.10 Wood et al followed these patients clinically and radiographically for a mean of 44 months (minimum of 24 months). Forty-seven patients were available for final examination (follow-up rate of 89%). The operative group (n = 24 patients) underwent posterior or anterior arthrodesis and instrumentation, and the nonoperative group (n = 23 patients) were treated by application of closed reduction on a Risser-like cast table, and then a body cast or orthosis.

There was no significant difference in the duration of hospitalization or average fracture kyphosis, and canal compromise at the time of admission and at final follow-up. The visual-analogue scale (VAS),11 modified Roland and Morris disability questionnaire,12 Oswestry back-pain questionnaire13 and the Short Form-36 (SF-36) health survey14 were used to evaluate clinical outcomes. Overall final scores on the SF-36 and Oswestry questionnaires were similar for the two groups. The only significant differences between the groups were found with respect to physical function (p = 0.002) and physical role (p = 0.003) on SF-36 scores. No significant difference was found between the two groups with respect to pain at the time of presentation and final follow-up exam. Those who were treated nonoperatively reported significantly lower Roland and Morris functional disability scores (mean 8.16 points operative and 3.9 points nonoperative, p = 0.02). There was no association found between any clinical symptoms and radiographic parameters such as kyphotic fracture angle and percentage of correction lost at final follow-up. Cost of hospitalization was more than four times greater in the operative than the nonoperative group, and the complication rate was higher in the operative group.

This study marked the first prospective, randomized study to compare nonoperative to operative treatment of neurologically intact patients with a stable burst fracture of the thoracolumbar junction (T10–L2). The authors found no major long-term advantage of operative compared with nonoperative treatment of neurologically intact patients with a stable thoracolumbar burst fracture. Limitations of this study include the six patients (11%) lost to follow-up and the relatively small numbers.

Another randomized prospective clinical trial was performed in 80 neurologically intact patients with single-level burst fractures (T11–L2) by Shen et al.15 Forty-seven patients were treated nonoperatively (allowed activity until the point of pain in a hyperextension brace), and 33 patients were treated operatively by posterior three-level fixation. Lower pain scores were seen up to 3 months and improved Greenough Low Back Outcome Scores up to 6 months in the surgical group. However, at 2 years follow-up pain scores (1.5 ± 1.3 and 1.8 ± 1.3) and Low Back Outcome Scores (65 ± 10 and 61 ± 11) were equivalent.

Radiographically, the kyphosis angle increased in the non-surgical group by an average of 4 degrees (range, 24 degrees to 6 degrees). In the surgical group, there was good initial correction of the kyphosis angle from an average of 23 degrees to 6 degrees (corrected by 17 degrees). However, even with use of the more rigid three-level fixation technique, the correction was gradually lost by the 2-year time point—the kyphosis angle increased to 12 degrees. The increased kyphosis angle, however, did not correlate with clinical outcomes. Short-segment posterior fixation appeared to provide early kyphosis correction and some pain relief; however, hospital charges were four times higher in the surgical group. This level II study was limited by a high level of patient crossover (seven patients initially randomized to the surgical group refused surgery).

A multicenter prospective study in which 34 neurologically intact patients were randomized to surgery and conservative care was performed by Siebenga et al.16 Inclusion criteria were a traumatic fracture (T10–L4) and AO type A morphology (excluding AO type A.1.1). At a mean follow-up of 4.3 years, both local and regional kyphotic deformity was significantly less in the operatively treated group; however, no correlation was found between radiographic and functional results in both groups. Functional outcome scores [VAS pain, VAS spine score, and RMDQ-24 (Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire) validated questionnaire] were significantly better in the operative group, and a significantly higher return to their original job was found as well.

Level III Data

Four studies met the criteria for level III evidence.

Domenicucci et al17 retrospectively studied 31 patients with thoracolumbar fractures, 20 treated conservatively and 11 operatively. The short-term radiographic results of both treatment groups were satisfactory; however, the long-term radiographic results were considered less favorable in patients treated conservatively. The long-term radiographic results, however, were not associated with clinical deterioration (pain and functional recovery) in patients with a sagittal index of less than 20. In a cross-sectional study performed by Kraemer et al,18 24 patients with thoracolumbar burst fracture without neurological deficit were administered the SF-36 survey. Of the eight patients managed surgically and the 16 patients treated conservatively, there was no difference in the functional outcome between the two groups. It is difficult to draw conclusions from these studies, given the small size of the study groups.

Twenty-six neurologically intact patients with L1 burst fractures were reviewed retrospectively by Butler et al.19 Fifteen patients treated nonoperatively and 11 operatively were followed for a mean period of 43 months (range, 14 to 80). There was no correlation between vertebral collapse, kyphosis, retropulsion, and clinical outcome. Twelve of 15 patients treated nonoperatively described little or no pain, and eight returned to the same level of recreational activity as to prior to the injury. Four of 11 surgically treated patients experienced little or no pain, and three returned to the same level of recreational activity prior to the injury. Overall, patients treated nonoperatively reported good functional outcomes, and those who required surgical stabilization reported poorer functional outcomes. Patients selected for surgical treatment had one of the following characteristics: greater than 50% anterior body compression, greater than 15 degrees kyphosis, or greater than 50% spinal canal compromise. Patients not meeting these criteria were managed conservatively. This study was thus limited by these different injury patterns in each of the treatment groups.

The retrospective analysis by Denis et al4 reported on 52 patients with thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurological deficits. Thirteen patients were treated with Harrington instrumentation, and 38 patients were treated nonoperatively. Mean follow-up period was 42 months in the nonoperative group and 36 months for the operative group. In the operative group, no patient developed neurological problems; however, 17% of patients in the nonoperative group were reported to develop neurological symptoms—primarily urological. Moreover, an unacceptably large number of patients (25%) in the nonoperative group were unable to return to work. In the operative group, all patients were able to return to work full time. Denis and colleagues thus recommended stabilization and fusion of thoracolumbar burst fractures in the neurologically intact patient; however, they conceded the need for future prospective studies. One flaw of this study is that, while the authors reported the overall distribution of Denis classification types in their study, they did not report the distribution in each treatment group.

Summary of Data

There is limited level II data that suggest there is no major long-term advantage of operative compared with nonoperative treatment of neurologically intact patients with a stable thoracolumbar burst fracture.10 However, another level II study suggests the opposite, that improved functional outcome scores may be seen in those treated surgically.16 Across all studies, there was no correlation between the final amount of kyphosis and the clinical outcomes in terms of pain and disability. This is consistent with prior studies that have shown that the correlation between posttraumatic back pain and radiographic parameters (e.g., progression of kyphosis, canal clearance) is poor on long-term follow-up.2,20

There is limited level III data to suggest that long-term radiographic results were less favorable in patients treated conservatively. Conservative treatment did not negatively influence clinical outcome (pain and functional recovery) in patients with a sagittal index of less than 20.17 There is no conclusive level III data to suggest a benefit for surgical or conservative treatment.4,18,19

Pearls

• Level II evidence suggests there is no correlation between the final amount of kyphosis and the clinical outcomes in neurologically intact patients with a stable thoracolumbar burst fracture.

• Additional level II data suggest there is no long-term advantage of operative compared with nonoperative treatment of neurologically intact patients with a stable thoracolumbar burst fracture.

• There are no level I data comparing operative and nonoperative treatment of burst fractures without a neurological deficit.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree