Tic Disorders

Michael H. Bloch

James F. Leckman, M.D

Tic disorders are transient or chronic conditions associated with difficulties in self-esteem, family life, social acceptance or school or job performance that are directly related to the presence of motor and/or phonic tics. Tic disorders have been noted since antiquity. The first identified case of TS in historical literature was recounted in Malleus Maleficarium (The Witches’ Hammer), a 1482 treatise on recognizing and curing demonic possession. Sprenger and Kraemer, the authors of Malleus Maleficarium, provide a detailed description of a young priest with motor and vocal tics, who is saved from a fiery death at the stake only by successful treatment with exorcism (1). In later French historical archives, there is a chilling account of one Prince de Conde, a seventeenth century French nobleman in the court of Louis XIV, who resorted to stuffing objects in his mouth to prevent an involuntary bark when in the presence of his royal highness (2).

Although reported since antiquity, recognition of TS as a distinct neuropsychiatric syndrome, and systematic study of individuals with tic disorders, began only with the reports of French neurologists Itard (1825) and Gilles de la Tourette (1885) in the nineteenth century. Gilles de la Tourette, in his classic study of 1885, described nine cases characterized by motor “incoordinations” or tics, “inarticulate shouts accompanied by articulated words with echolalia and coprolalia (3).” In addition to identifying the cardinal features of severe tic disorders, his report noted an association between tic disorders and obsessive-compulsive symptoms, as well as the hereditary nature of the syndrome in some families.

Since the case series presented by Gilles de la Tourette, we have learned that TS typically has a much more benign course than initially suggested in his account. We have also developed some effective pharmacological, psychological, and now, even surgical, treatments for individuals with TS. With increasing longitudinal assessment of children with tic disorders we have learned that many present or develop a broad array of behavioral difficulties, including disinhibited speech or conduct, impulsivity, distractibility, motoric hyperactivity, and obsessive compulsive symptoms (4). In this chapter, a presentation of the phenomenology and classification of tic disorders precedes a review of the epidemiology, clinical course, neurobiological substrates, assessment and management of tic disorders and their associated comorbidities.

Definition

Tics are sudden, repetitive movements, gestures, or phonic productions that typically mimic some aspect of normal behavior. Usually of brief duration, individual tics rarely last more than a second. Many tics tend to occur in bouts, with brief inter-tic intervals of less than one second (5). Individual tics can occur singly or together in an orchestrated pattern. They vary in their intensity or forcefulness. Motor tics, which can be viewed as disinhibited fragments of normal movement, can vary from simple, abrupt movements such as eye blinking, nose twitching, head or arm jerks, or shoulder shrugs to more complex movements that appear to have a purpose, such as facial or hand gestures or sustained looks. These two phenotypic extremes of motor tics are classified as simple and complex motor tics respectively. Similarly, phonic tics can be classified into simple and complex categories. Simple vocal tics are sudden, meaningless sounds such as throat clearing, coughing, sniffing, spitting, or grunting. Complex phonic tics are more protracted, meaningful utterances, which vary from prolonged throat clearing to syllables, words or phrases, to even more complex behaviors such as repeating one’s own words (palalalia) or those of others (echolalia) and, in rare cases, the utterance of obscenities (coprolalia) (6). Clinicians typically characterize tics by their anatomical location, number, frequency, duration, forcefulness and complexity as outlined above. Each of these elements has been incorporated into clinician rating scales that have proven to be useful in monitoring tic severity (7).

Many individuals with tics, especially those above the age of ten, are aware of premonitory urges that may either be experienced as a focal perception in a particular body region where the tic is about to occur (like an itch or a tickling sensation) or as a mental awareness (8,9). A majority of patients also report a fleeting sense of relief after a bout of tics has occurred, and most individuals are able to suppress their tics for short intervals of time (9,10).

Diagnostic Classification

The currently accepted diagnostic criteria for TS as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Text-Revision (DSM-IV-TR) include: 1) presence of multiple motor tics, 2) presence of one or more vocal tics, 3) onset before age 18, 4) tics that may appear many times a day, either everyday or intermittently, 5) presence of tics for a period longer than 1 year, 6) change in anatomic location and character of tics over time and 7) occurrence of tics not attributable to CNS disease (Huntington disease or postviral encephalopathies) or psychoactive medication or substance usage (Table 5.6.1).

Tics that appear in childhood are often ephemeral. When a patient exhibits motor and/or vocal tics for less than a year, a diagnosis of a transient tic disorder is made, regardless of tic frequency or severity. If either motor or phonic tics (but not both) are present for a year or more, then a diagnosis of chronic motor or phonic tic disorder, respectively, can be made, according to DSM-IV-TR. Chronic tics are viewed by experts

as a milder phenotypic expression of TS, while transient tic disorders are generally viewed as a separate entity (4).

as a milder phenotypic expression of TS, while transient tic disorders are generally viewed as a separate entity (4).

TABLE 5.6.1 DSM-IV-TR TIC DISORDER CLASSIFICATION | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clinical Course of TS

The onset of TS is usually characterized by the appearance of simple, transient motor tics that affect the face (typically eye blinking) around the age of 5–7 (11). Over time these simple motor tics generally progress in a rostrocaudal direction affecting other areas of the face, followed by the head, neck, arms and last and less frequently, the lower extremities (12). Phonic tics usually appear several years after the onset of motor tic symptoms, at 8–15 years of age. Phonic tics seldom appear in isolation without the prior onset of motor tics— fewer than 5% of all patients with tic disorders have isolated phonic tic disorder, whereas the vast majority of children afflicted with tic disorders have isolated motor symptomatology (10). Tic complexity, also, generally evolves with age. During the first years of TS onset there is a steady unfolding of symptoms with single, rapid motor tics evolving into stereotyped, complex movements and nonsense sounds developing into elaborate words and phrases. The character of these complex phonations and movements are highly unique to the individual. Due to the rapid progression of symptoms during childhood, the vast majority of TS cases are diagnosed by age 11 (10).

Typically, as they grow older, children with TS gain an increasing ability to recognize when tics will ultimately strike and gain control over them. The first transient motor tics TS patients experience in the latency years are usually sudden, involuntary, unconscious movements. Often the afflicted individual is only made aware of the presence of these movements through the reactions of others around him. By the age of 10 or 11, however, many children report premonitory urges: feelings of tightness, tension, or itching that are accompanied by a mounting sense of discomfort or anxiety that can be relieved only by the performance of a tic (9). These premonitory urges are similar to the sensation preceding a sneeze or an itch. Premonitory urges cause many TS patients to suffer from an endless cycle of rising tension and tic performance because the relief provided by tic performance is ephemeral. Thus, soon after tic performance the tension of the premonitory urge again rises to a crescendo (13).

With increasing awareness of premonitory urges, TS patients begin to exhibit a variable degree of voluntary control over tic performance. Ninety-two percent of TS subjects in one study reported that the tics they exhibited were either partially or totally voluntary (9). However, this voluntary control should be likened to that governing control of eye blinking. Eye blinking and tics can both be inhibited voluntarily, but only for a limited period of time and only with mounting discomfort. Thus, some adult TS patients are able to demonstrate nearly complete control over the situation when expression of their tics will occur. However, when complete or near complete control of tics is present, resistance to the mounting tension of premonitory urges can produce mental and physical exhaustion even more impairing and distracting than the tics themselves (12).

The severity of tics in TS waxes and wanes throughout the course of the disorder. The tics of TS and other tic disorders are highly variable from minute to minute, hour to hour, day to day, week to week, month to month and even year to year (5). Tic episodes occur in bouts, which in turn also tend to cluster. Tic symptoms, however, can be exacerbated by stress, fatigue, extremes of temperature and external stimuli (in echolalia tics) (14). Intentional movements attenuate tic occurrence over the affected area and intense involvement and concentration in activities tends to dissipate tic symptoms. The power of this effect in many patients with TS is illustrated beautifully in Oliver Sacks’ short story, A Surgeon’s Life. As Sacks writes:

And, indeed, whenever the stream of attention and interest was interrupted, Bennett’s (the surgeon) tics and iterations immediately reasserted themselves— in particular, obsessive touchings of his mustache and glasses. His mustache had constantly to be smoothed and checked for symmetry, his glasses had to be “balanced”— up and down, side to side, diagonally, in and out— with sudden, ticcy touchings of the fingers, until these, too, were exactly “centered.” There were also occasional reachings and lungings with his right arm; sudden, compulsive touchings of the windshield with both forefingers (“the touching has to be symmetrical,” he commented); sudden repositionings of the knees, or the steering wheel (“I have to have the knees symmetrical in relation to the steering wheel. They have to be exactly centered”); and sudden, high-pitched vocalizations, in a voice completely unlike his own, that sounded like “Hi, Patty,” “Hi, there,” and, on a couple occasions, “Hideous!”

Sacks keenly observes that Dr. Bennett’s tics and tic-related compulsive behavior are noticeably absent in two situations: 1) in the morning when he is conducting preparatory reading for his later surgeries while simultaneously riding an exercise bike and 2) when performing surgery (15).

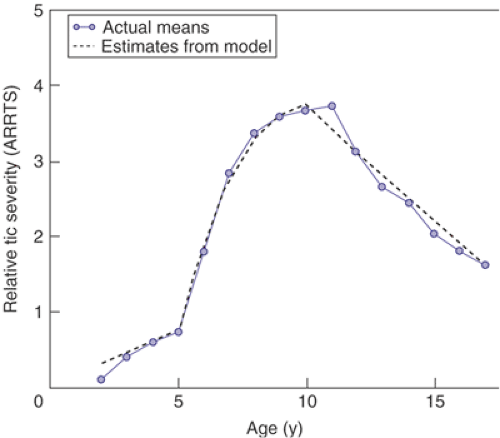

Tic severity, however, typically dissipates with the onset of adolescence. TS symptoms generally peak in severity between the ages of 8 and 12 (11,16). Reduction in TS severity generally ends by the early 20s. Although a small minority of TS patients does experience catastrophic outcomes in adulthood, on the whole, individuals rarely experience either a sustained worsening or improvement of their symptoms after the third decade of life. One-half to two-thirds of individuals with TS experience a marked reduction of symptoms by their late teens and early 20s, with one-third to one-half becoming virtually asymptomatic in adulthood (11,17). Figure 5.6.1 diagrams the general course of tic severity of TS patients through the first two decades of their illness (11,16).

Prevalence

Transient tic behaviors are commonplace among children. Studies have estimated that 4–24% of school-age children experience tics (18,19,20,52). The upper end of this estimate was based on a study by Snider et al. (2002) that assessed a community sample of 553 children ages 5–12 years in a suburban elementary school (19). Assessment was obtained by direct observations by trained observers on each child over multiple occasions over an 8-month period. Snider et al. estimated that 18% of the children (n = 101) experienced a single tic or transient tics. A much smaller portion (n = 34), 6%, had multiple or persistent tics. A similar study by Khalifa and von Knorring examined the prevalence of tic disorders in an epidemiologic sample of 4,479 Swedish children ages 7–15 using a three-stage evaluation procedure including screening, parental interview, and clinical assessment. This study estimated the prevalence of chronic motor tics at 0.7% and transient tics at 4.5% in this sample (20). The difference in prevalence measurements of transient and persistent motor tic disorders reported in these studies is likely due to their different ascertainment methods (parent interview vs. direct observation). Nonetheless, the relative commonness of transient tics in the school-age population is evident in both these studies and the difference in prevalence between transient and multiple tic disorders is relatively conserved across studies.

Although boys are more commonly affected with tic behaviors than girls, the male–female ratio in most community surveys is less than 2 to 1. For example, in the Isle of Wight study of 10 to 11 year olds, approximately 6% of boys and 3% of girls were reported by their parents to have “twitches, mannerisms, tics of face or body (18).” Similar estimates have been reported from Quebec and from North Carolina (22,23).

There exists drastic variation in estimates of prevalence of TS in the published medical literature. Once thought to be rare, current estimates vary 100 fold, from 2.9 per 10,000 to 299 per 10,000 (24,25). There are three main reasons for this variation in the measurement of the estimation of TS prevalence: 1) The prevalence and severity of tic disorders varies drastically as a function of age (with highest prevalence and greatest severity taking place late in the first decade and early in the second decade of life, and decreasing roughly with the onset of puberty), 2) assessment method of individual studies has varied (patient registries, parent interview, direct observation vs. clinically ascertained cases) and 3) the diagnostic criteria of TS has changed with time— specifically, whether the diagnosis of TS requires an impairment criteria. DSM-III included a requirement that tic symptoms need to “cause marked distress of significant impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning” in order to qualify as TS. By contrast, the impairment criteria was removed in DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10. Estimates of TS prevalence since 1990 among school-age children have estimated a prevalence somewhere between 10 to 100 per 10,000 20,26,27,28,29,30. Studies incorporating the older DSM-III definition of TS have estimated the prevalence of TS around the lower end of this range, while studies relying on the newer DSM-IV definition of TS not incorporating an impairment criteria have estimated TS prevalence toward its higher end. Estimates of older teenagers and adults with TS is considerably lower, at approximately 4.5 per 10,000 and this result is not surprising since many cases of TS improve drastically or remit completely during the course of adolescence (31).

Coexisting Conditions

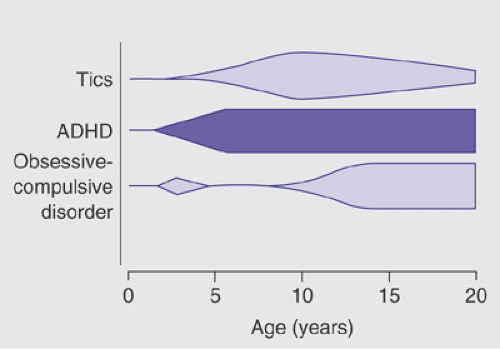

Tics, which are the most prominent feature of TS, are often neither the first nor the most impairing psychological disturbance endured by patients. It has become apparent that children with TS have higher rates of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and disinhibited speech and behavior compared to individuals in the general population. In one study, 65% of TS patients in late adolescence regarded their behavioral problems (including ADHD and OCD) and learning difficulties to have had an equal or greater impact on their life function than did the tics themselves (32). In the natural course of comorbid psychiatric illness in TS, ADHD symptoms, when they occur, typically precede the onset of tic symptoms by a couple of years, whereas OC symptoms typically present around the age of 12–13 after tics have reached their peak severity (11,16) (Figure 5.6.2).

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Clinical and epidemiological studies sharply differ on rates of ADHD seen among individuals with TS (33). Clinical studies vary according to setting and established referral patterns, but it is not uncommon to see reports of 50% or more of referred children with TS diagnosed with comorbid ADHD. In contrast, epidemiological studies typically indicate a much lower rate of comorbidity (31). Although the etiological relationship between TS and ADHD is in dispute, it is clear that those individuals with both TS and ADHD are at a much greater risk for a variety of untoward outcomes (34). Uninformed peers frequently tease individuals with TS and ADHD. They are often regarded as less likeable, more aggressive, and more withdrawn than their classmates (35). These social difficulties are amplified in a child with TS who also has ADHD (36). In such cases, their level of social skill is often several years behind their peers (37).

Negative appraisal by peers in childhood is a strong predictor of global indices of psychopathology (38). This appears to be particularly true for children with TS and ADHD. Children with TS and comorbid ADHD are at much greater risk for disruptive behavior disorders and functional impairment from psychiatric illness than children with TS alone (39). Longitudinal studies confirm that these individuals are at high risk for anxiety and mood disorders, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder (34,40). Much of this negative impact appears to be due to the ADHD, as children who only have TS tend to fare better (34,39,41). Surprisingly, levels of tic severity are less predictive of peer acceptance than is the presence of ADHD (36). Furthermore, the rates of subsequent psychiatric morbidity seen in TS plus ADHD subjects are nearly identical to those seen in prior cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of ADHD subjects who do not have tics (42,43).

Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms

Clinical and epidemiological studies indicate that more than 40% of individuals with TS experience recurrent obsessive-compulsive (OC) symptoms (16,44,45). Genetic, neurobiological, and treatment response studies suggest that there may be qualitative differences between tic-related forms of OCD and cases of OCD in which there is no personal or family history of tics. Tic-related OCD tends to have an earlier age of onset, prior to the age of 12–13, compared to non–tic-related OCD, which usually appears during late adolescence or early adulthood. Patients with OCD and comorbid tics have a significantly higher rate of intrusive violent or aggressive thoughts and images; sexual and religious preoccupations; concerns with symmetry and exactness; hoarding and counting rituals; and touching and tapping compulsions compared to patients with non-tic OCD, who often suffer primarily from contamination worries and cleaning compulsions (44,46). Compulsions designed to eliminate a perceptually tinged mental feeling of unease, coined in the literature as “Just Right” perceptions, are particularly typical of patients with OCD and comorbid tics (45). A new rating scale, the Dimensional Yale–Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DY–BOCS), was designed to measure the presence and severity of OCD symptoms within six thematically related dimensions and should aid in further discriminating the OCD experienced by patients with TS compared to those with comorbid tics (47,48). In addition, tic-related OCD is significantly less responsive to pharmacological therapy with SRIs than non–tic-related OCD and appears to be more responsive to augmentation with antipsychotic agents (49,50).

In a previous prospective longitudinal study the presence of tics in childhood and early adolescence predicted the future development of OCD (30). Similarly, in a recent followup study of adult outcomes in children with TS, 41% of TS patients experienced at least moderate obsessive-compulsive symptoms in adulthood, with these symptoms reaching their worst-ever severity between the ages of 12–13 years, an average of 2 years later than tics (16). Also, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, when present in children with TS, appear more likely to persist into adulthood than the tics themselves (16). Higher intelligence may also herald a higher risk of developing more severe OCD symptoms in adulthood (16).

Etiology

Genetic Factors

TS and other closely related disorders clearly have a strong genetic component. The overall risk of an offspring of a parent with TS developing TS is approximately 10–15%; the risk of their offspring developing a tic disorder (20–29%) or OCD (12–32%) is slightly higher (51,52,53,52). The risk of developing tic disorders in male offspring is higher, while the risk of developing OCD is less. Twin and family studies provide evidence that genetic factors are involved in the vertical transmission within families of a vulnerability to TS and related disorders (55). The concordance rate for TS among monozygotic twin pairs is greater than 50 percent, while the concordance of dizygotic twin pairs is about 10 percent (56,57). If cotwins with chronic motor tic disorder are included, these concordance figures increase to 77 percent for monozygotic and 30 percent for dizygotic twin pairs. Differences in the concordance of monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs indicate that genetic factors play an important role in the etiology of TS and related conditions. These figures also suggest that nongenetic factors are critical in determining the nature and severity of the clinical syndrome.

Several studies involving segregation analysis of large multigenerational families have implicated the possible importance of single gene(s) inherited with an autosomal dominant pattern in the pathogenesis of TS (53,55,58). Unfortunately, genetic linkage studies that have screened the entire genome have eliminated the possibility of a single gene being responsible for TS (59). More recently, nonparametric approaches using families in which two or more siblings are affected with TS have been undertaken (60). This sib-pair approach is suited for diseases with an unclear mode of inheritance and has been used successfully in studies of other complex disorders such as diabetes mellitus and essential hypertension. In this study, two areas are suggestive of linkage to TS, one on chromosome 4q and another on chromosome 8p. Currently, this international consortium of researchers is actively completing high-density maps of several genomic regions in an effort to refine and extend their preliminary results. In addition, a new sample of sibling pairs is being ascertained to determine if the linkage results on 4q and 8p can be replicated.

It is also noteworthy that none of the chromosomal regions (e.g., 3 [3p21.3], 8 [8q21.4], 9 [9pter], and 18 [18q22.3]) in which cytogenetic abnormalities have been found to co-segregate with TS showed any convincing evidence for linkage in the sib-pair study. It is still possible that rare susceptibility genes may be found in one or more of these regions using molecular cytogenetic techniques. Furthermore, none of the regions associated with candidate genes, such as DRD2 [11q22] and DRD4 [11p15], were supported by the results of the sib-pair study.

Recently, using a candidate gene approach identified by chromosomal anomalies in patients with TS, Abelson et al. (61) identified and mapped a de novo chromosome 13 inversion in a patient with TS. The gene SLITRK1 was identified as a brain-expressed candidate gene mapping approximately 350 kilobases from the 13q31 breakpoint (61). Mutation screening of 174 patients with TS was undertaken, with the resulting identification of a truncating frame-shift mutation in a second family affected with TS. In addition, two examples of a rare variant were identified in a highly conserved region of the 3′ untranslated region of the gene corresponding to a brain-expressed micro-RNA binding domain. None of these anomalies were demonstrated in 3,600 controls. In vitro studies showed that both the frame-shift and the miRNA binding site variant had functional potential and were consistent with a loss-of-function mechanism. Studies of both SLITRK1 and the micro-RNA predicted to bind in the variant-containing 3′ region showed expression in multiple neuroanatomical areas implicated in TS neuropathology, including the cortical plate, striatum, globus pallidus, thalamus, and subthalamic nucleus.

Perinatal Factors

The search for nongenetic factors that mediate the expression of a genetic vulnerability to TS and related disorders has also focused on the role of adverse perinatal events. This interest dates from the report of Pasamanick and Kawi, who found that mothers of children with tics were 1.5 times more likely to have experienced a complication during pregnancy than the mothers of children without tics (62). Other investigations have reported that among monozygotic twins discordant for TS, the index twins with TS had lower birth weights than their unaffected cotwins (57,63). Severity of maternal life stress during pregnancy, severe nausea and/or vomiting during the first trimester have also emerged as potential risk factors in the development of tic disorders (64). In 1997, Whitaker and coworkers reported that premature and low birth weight

children are at increased risk of developing tic disorders and ADHD. This appears to be especially true of children who had ischemic parenchymal brain lesions. More recently, Burd and colleagues (1999) presented the results of a case control study in which low Apgar scores at 5 minutes and more prenatal visits were associated with a higher risk of TS (65). Finally, there is limited evidence that smoking and alcohol use, as well as forceps delivery, can predispose individuals with a vulnerability to TS to develop comorbid OCD (66). Investigations into the effects of perinatal complications into the later development of TS are severely hampered by 1) the possibility that recall bias likely influences results in the retrospective case-control studies addressing this question and 2) multiple hypothesis testing without appropriate statistical correction. The only nested case-control study to date that examined TS cases arising in a Swedish community sample (rather than a clinically referred sample) found a higher rate of pre-, peri- and neonatal adverse events between TS patients and controls, but this difference was not significant (67).

children are at increased risk of developing tic disorders and ADHD. This appears to be especially true of children who had ischemic parenchymal brain lesions. More recently, Burd and colleagues (1999) presented the results of a case control study in which low Apgar scores at 5 minutes and more prenatal visits were associated with a higher risk of TS (65). Finally, there is limited evidence that smoking and alcohol use, as well as forceps delivery, can predispose individuals with a vulnerability to TS to develop comorbid OCD (66). Investigations into the effects of perinatal complications into the later development of TS are severely hampered by 1) the possibility that recall bias likely influences results in the retrospective case-control studies addressing this question and 2) multiple hypothesis testing without appropriate statistical correction. The only nested case-control study to date that examined TS cases arising in a Swedish community sample (rather than a clinically referred sample) found a higher rate of pre-, peri- and neonatal adverse events between TS patients and controls, but this difference was not significant (67).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree