OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Review the epidemiology of patients who smoke tobacco.

Describe other types of tobacco used by vulnerable populations.

Describe the health consequences of tobacco use and its impact on the health-care system.

Describe the challenges that tobacco use poses to patients, clinicians, and communities.

Identify strategies to treat tobacco dependence including clinical, policy-level, and systems-level interventions.

Clarence Jones is a 44-year-old man brought to the emergency room via ambulance in respiratory distress. He has had five admissions within the past year for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations and has been intubated during each admission. He has been smoking since he was 8 years old and smokes up to two packs a day.

INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable, premature morbidity and mortality in the United States and in many countries around the world. Smokers, on average, die 10 years earlier than nonsmokers.1 Tobacco use is a major cause of death from cancer, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary disease. Smoking accounts for 6% or more of total American medical costs.2 Patterns of tobacco use are the result of the complex interactions of a multitude of factors, including socioeconomic status, culture, acculturation, poor access to medical care, targeted advertising, relative affordability of tobacco products, and varying capacities of communities to mount effective tobacco control initiatives. It is clear that helping smokers quit may be the most important act health-care providers do. This chapter reviews the epidemiology, the health effects of cigarette smoking and other tobacco use, and the challenges to treating tobacco dependence, particularly among vulnerable populations where tobacco use is concentrated. It discusses some strategies for confronting these challenges.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TOBACCO USE

In 2012, an estimated 42.1 million Americans were smokers.3 Of these, about three-fourths were daily smokers, and about one-fourth intermittent smokers. Over time, the prevalence of smoking has declined, from a high of 42.7% in 1965 to the current level of 18%. The decrease in male smoking prevalence is even more dramatic, falling from a high of 54% in 1955 to the current level of 20.5%.4 Smoking among women rose to a high of 34% in 1964, before its decline to the current level of 16%.3

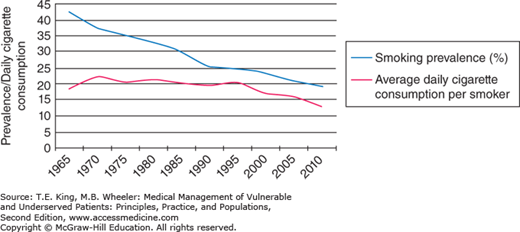

It was initially hypothesized that quitting smoking would be easier for light and intermittent smokers, and thus as a result the remaining smokers would be more hardcore. But that has not turned out to be the case. Until 1995, smokers consumed, on average, 20 cigarettes daily. Beginning in 1995 that number began to fall, and today the average smoker smokes about 13 cigarettes per day, with about 22% of all smokers not smoking every day (Figure 40-1). Although 70% of smokers state that they would like to quit, only about 5% are able to do so, with the number being higher for those seeking medical assistance with quitting. For most smokers who want to quit, it takes as many as 10–12 attempts before they succeed.

Figure 40-1.

Smoking prevalence and average number of cigarettes smoked per day per current smoker, 1965–2010. (Adapted from Schroeder SA. How clinicians can help smokers to quit. JAMA 2012. 308(15):1586-1587.)50

Differences in smoking prevalence exist among racial and ethnic groups, with Native Americans having the highest rate (31.5%), followed by whites (20.6%), African Americans (19.4%), Hispanics (12.9%), and Asians (9.9%). Substantial differences exist within these broad groups. For example, smoking rates among Americans of Korean descent are much higher than those of Filipino ancestry.5 It may seem paradoxical that Asian-American men have relatively low smoking rates, since in their home countries (China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam) male smoking rates exceed 50%. There is no evidence of selective immigration by nonsmoking Asian men, and studies have found that Asian immigrant smokers have high post-immigration cessation rates as a process of acculturating to a nation that stigmatizes smoking.

In the period before World War II and up until the 1960s, men smoked at a much higher rate than women. Since then, the gap has narrowed but persisted. In 2012, men’s smoking prevalence was 20%, compared with women’s rate of 16%.3 For youth, however, girls now have equal or higher smoking rates than boys.

A steady decline in smoking prevalence during pregnancy has followed the warnings that smoking is the most important contributor to premature delivery. However, only about one-third of women who stop smoking during pregnancy are still abstinent 1 year later. The highest rates of smoking during pregnancy occur among younger women, white or Native American women, and women of lower socioeconomic classes.

Once a badge of sophistication, tobacco use is now disproportionately concentrated among marginalized populations. These include persons with mental illness, substance use disorders including alcohol and illicit drugs, incarcerated populations, the homeless population, and the LGBT community. As smoking has become stigmatized, it is also increasingly concentrated among those with low socioeconomic status. There are very high rates among those with General Educational Development (GED) diplomas, for example. Compared with the general population (18%), smoking prevalence rates among these groups are two to four times as high, despite the fact that the steep price of a pack of cigarettes exerts a substantial financial toll on many of these vulnerable persons. By contrast, the rate of smoking among US physicians is between 1% and 2%, among the lowest in the world.

Smoking prevalence in low- and middle-income countries is generally higher than in developed nations, and much higher among men than among women. Rates are especially high among Asian men and the former Soviet Republics, including Russia, and relatively low among women in Africa, South East Asia, and most of Latin America, except for Chile and Paraguay. Although overall worldwide smoking prevalence decreased between 1980 and 2012 from 41% to 31% for men and from 11% to 6% for women, because of population growth the absolute numbers of smokers globally actually increased, from 718 million to 966 million. The highest rates of smoking for men include Russia and Indonesia (>50%) and for women Greece and Bulgaria (>30%).6

OTHER TYPES OF TOBACCO

Although cigarettes are the most common form of tobacco product used in the United States, a wide variety of other tobacco products exist. Non-cigarette forms of tobacco can be categorized into three groups: other combustible tobacco, smokeless forms of tobacco, and electronic nicotine delivery systems.7

Cigars, pipes, water pipes, and roll-your-own tobacco comprise the major forms of other combustible tobacco used in the United States. Cigars contain shredded tobacco, wrapped in a tobacco leaf, and are produced as little cigars (manufactured and packaged as cigarettes), cigarillos, or large cigars. Pipes consist of a bowl that holds the tobacco, and an attached stem, where smoke is drawn, whereas water pipes (otherwise known as shisha, hookah, or narghile) use an indirect heating mechanism where smoke from the burned tobacco is passed through a container filled with water before reaching the user via a hose. Bidis and kreteks are made from loose-leaf tobacco, and are used frequently in other parts of the world including South Asia and South-East Asia, and among US immigrants from these regions. While the exclusive use of these products is low in the United States, dual use of cigarettes and other combustible tobacco products is common among youth, persons with low incomes, and those with low educational attainment.8 The lower prices of these products compared to cigarettes, the wide variety of flavors, and the perception that these products are less harmful than cigarettes have contributed to the increase in the use of other combustible forms of tobacco.

Smokeless tobacco is a broad term for tobacco products that are used orally or nasally, and include chewing tobacco, snuff, snus, and newer dissolvable tobacco products. Chewing tobacco is sold as long strands of tobacco, which are chewed or placed in between the cheeks, gums, or teeth. The nicotine is absorbed through the tissues of the mouth, and the user spits out the tobacco after its use. Snuff and snus are finely ground tobacco that are sold in their dry or moist forms, and used in a manner similar to chewing tobacco, without the need for spitting. Other types of newer dissolvable tobacco products include tobacco lozenges or pellets or toothpick like strips, which are produced in a wide variety of flavorings that appeal to youth and young adult populations. Exclusive use of smokeless tobacco is more common among men than among women, and is highest among the young adult population (18–24 years) and those with less than a high school education. Dual use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco is more prevalent among youth and young adults, those with low incomes, and low educational attainment.

Electronic nicotine delivery systems originated in China in 2006, and became available worldwide between 2008 and 2009. Otherwise known as e-cigarettes, these devices are constructed to resemble cigarettes, and deliver a vaporized solution of nicotine. They come in a wide variety of flavorings (e.g., licorice, chocolate, and strawberry), which appeal to youth and young adults. Consequently, use of e-cigarettes among the youth and young adult population has increased substantially in recent years. The prevalence of e-cigarette use doubled between 2011 and 2012 from 3.3% to 6.8% among youths in grades 6 through 12, and from 6.2% in 2011 to 3.3% in 2010 among adults.9

HEALTH CONSEQUENCES OF TOBACCO USE

Tobacco use accounts for about 480,000 deaths annually in the United States and more than 5 million worldwide. An additional 8 million persons suffer from diseases caused by smoking in the United States alone. The list of diseases caused by tobacco use is large, and it continues to expand over time. For some illnesses, such as lung cancer, the risks are staggering. But all of the conditions listed in Table 40-1 are more likely to occur if a person uses tobacco, especially combustible tobacco.

| Cancer | Cardiovascular | Pulmonary | Gastrointestinal |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Infection | Other | Reproductive | |

|

|

|

In addition to the health consequences of active smoking, inhalation of secondhand smoke is also dangerous, accounting for an estimated 50,000 of the annual 480,000 deaths in the United States. The major causes of death from secondhand smoke exposure are diseases of the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems. Persons with these conditions can be harmed from minimal exposure to passive smoking, because even very low exposure to cigarette smoke causes changes in platelet adhesiveness and arterial endothelial function. Secondhand smoke can also increase the odds of lung cancer, nasal sinus cancer, exacerbations of asthma and other respiratory conditions, and decreased hearing in teenagers. Reproductive and developmental problems from secondhand smoke exposure include premature delivery, low-birth-weight infants, sudden infant death syndrome, childhood depression, and childhood middle ear disease. In some states and communities, it is illegal to smoke in an automobile if children are present. Cigarette-induced fires cause burns, smoke inhalation damage, and death. Pediatricians have publicized the risk of thirdhand smoke exposure, which occurs when infants and young children orally ingest tobacco smoke residues that have accumulated on the clothes and furniture of smokers. These chemicals can exacerbate respiratory and middle ear infection and are potentially carcinogenic.

Smokeless tobacco, while not as harmful as combustible products, also carries health risks, most notably oral and pharyngeal cancers, and also leukoplakia, gingivitis and gingival recession, poor recovery from oral surgery, and staining of teeth. Ingestion of tobacco products, including the nicotine found in electronic cigarettes, is an increasingly common cause of childhood poisoning. Data on the risks of using electronic cigarettes are emerging, as this product increases in popularity. The contents of e-cigarettes include propylene glycol, nicotine, nitrosamines and other known carcinogens, and ultrafine particles. While less harmful than combustible tobacco products, e-cigarettes have led to burns, explosions, and nicotine toxicity among children who ingest the contents of the cartridges.

Whether the e-cigarette is—on balance—helpful or harmful has stirred much debate in the tobacco control community. Opponents cite predatory marketing practices, packaging of the product in ways that appeal to youth, such as adding fruit or chocolate flavoring, the concern that e-cigarette usage will prove a gateway to combustible tobacco for youth, and that it will deter smoking cessation activities among established smokers. Others see the potential for great health benefit if smokers switch to e-cigarettes, which, although not proven to be safe, are likely safer than combustible tobacco. There is general consensus, however, around three points: there should be regulation of marketing practices so that the product is not marketed to youth; there should be no tolerance for e-cigarette vapor in public places; and we need to know more about the safety profile, the risk of serving as a gateway, and the potential for helping smokers quit. In April 2014, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a proposed rule that would extend to currently unregulated tobacco products including electronic cigarettes. Under the proposed rule, makers of these tobacco products would need to register with the FDA and report product ingredients, only market new tobacco products after FDA review, make direct and implied claims of reduced risk only after the FDA has confirmed scientific evidence, and not distribute free samples. In addition, makers of these products would be prohibited from selling their products to underage youth and would need to include health warnings on packaging. The FDA is expected to make a decision on its proposed rule in the near future.

IMPACT ON THE HEALTH-CARE SYSTEM

According to the 2014 report of the Surgeon General on the Health Consequences of Smoking, annual smoking-attributable costs in the United States were about $300 billion, including about $150 billion for medical care, about $150 billion from lost productivity due to premature deaths, and close to $6 billion from lost productivity due to secondhand smoke exposure.10

BENEFITS OF QUITTING

No matter how old a smoker is, she will accrue health benefits from quitting compared to what would have happened had she continued to smoke. For example, a smoker who quits at ages 25–34 saves an estimated 10 years of life. Benefits from quitting in the 35–44 years age group are 9 years, in the 45–54 years age group 8 years, and in the 55–64 years age group 4 years. Even for smokers older than 65 years, the risk of getting lung cancer or cardiovascular disease declines after stopping smoking.11 Return of function and reduction of risk following smoking cessation follow a predictable course. Within weeks to months, respiratory and circulatory function improves. By 1 year, the risk of coronary heart disease decreases to one half that of a continuing smoker and by 15 years the risk is at the level of never-smokers. For cerebrovascular disease, after 5 years, the risk is similar to never-smokers. Although the risk of lung cancer persists, by 10 years it is half that of a continuing smoker.

CHALLENGES TO MANAGING TOBACCO USE

Nicotine is a naturally occurring alkaloid found in combustible and noncombustible forms of tobacco. It is highly addictive and induces physical dependence and tolerance in a manner similar to other illicit substances, such as cocaine or heroin. In the brain, nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and triggers the activation of brain circuits that are involved in the reward system and habit formation. Chronic exposure to nicotine leads to widespread alterations in brain neurotransmission that sustains and promotes addiction. Smoking cessation disrupts these neuro-adaptations and leads to nicotine withdrawal. Symptoms of nicotine withdrawal such as depressed mood, insomnia, irritability, and anxiety act as potent deterrents to smoking cessation, and lead to maintenance of the smoking habit.

Nicotine dependence and the severity of nicotine withdrawal symptoms tend to be higher among persons with mental health disorders or substance use disorders; these individuals have higher rates of smoking than that of the general population. Many years of twin and adoption studies have demonstrated that nicotine dependence is a heritable trait. Genome-wide linkage and association studies have identified numerous genes (e.g., cholinergic nicotinic receptor subunit genes) associated with nicotine dependence that are located on chromosomes in close proximity to others linked with psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.12 These genetic factors are one of the many reasons for the increased severity of nicotine addiction among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders.

The first reports on the harmful effects of secondhand smoke were published in the 1980s. In the United States, legislation to ban smoking in the workplace was passed in 1994 and enacted in 1998, with California being the first state to implement smoke-free policies in the workplace.13 While the protection of nonsmokers was the primary intent of these policies, studies have shown that such policies are also associated with reduced prevalence of smoking and increased cessation among smokers.14,15 Since the mid-1990s, there has been a gradual expansion of smoke-free policies into public places, hospitality establishments, and hospitals. Until recently, correctional facilities, psychiatric hospitals, substance use recovery programs, public housing, and homeless shelters—settings that serve populations that are disproportionately affected by tobacco use—had a culture permissive of smoking. However, with changing norms around smoking in favor of stricter smoking restrictions and to protect nonsmokers from exposure to secondhand smoke, correctional facilities,16 psychiatric hospitals,17 and public housing18 have moved toward implementing indoor and outdoor smoke-free policies. Less is known about smoke-free policies in homeless shelters and substance use recovery programs. The absence of a consistent policy around smoking in facilities that serve marginalized populations reinforces the culture of tobacco use in these settings, and may contribute to the higher rates of tobacco use among these populations.

TOBACCO INDUSTRY MARKETING AND SOCIAL MEDIA

Television and movies promote tobacco use as a socially acceptable activity. Tobacco companies spend billions of dollars annually to market their products,19,20 and these marketing strategies are directed specifically toward youth and young adults, women, racial/ethnic minorities, and other vulnerable populations. The three most heavily advertised cigarette brands, Marlboro, Newport, and Camel, were the preferred brands of cigarettes smoked by adolescents and young adults between 2008 and 2011.21 Indeed, studies have shown the causal association between exposure to tobacco industry advertising and initiation of cigarette smoking among adolescents.22 Storefront cigarette advertising is more common in low-income communities, and these retail establishments are often situated within 1000 feet of a school.23 The close proximity of these convenience stores to schools increases children’s exposure to a wide variety of tobacco products, potentially leading to increased experimentation and sustained use.

The tobacco industry is estimated to spend more than $5 billion dollars annually in creating brands and marketing strategies that appeal to women.24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree