utterances and behavior is that of a rapid usually noncontextual explosion of words or actions, not to be confused with angry or antisocial statements of a frustrated or acting out child. TS patients often experience premonitory awareness of the onset of a tic. Attempts at suppression or alteration of tics may then present as a collection of odd voluntary motions or vocalizations meant to mask the underlying episode. These behaviors may phenomenologically overlap with symptoms of obsessive—compulsive disorder (OCD) as the child repetitively takes suppressive action to relieve tic tension. This is different from the pattern noted in OCD in which the action is often accompanied by thoughts related to symmetry, counting, phobic avoidance, or ritual. For patients with tic disorders and without OCD, the behaviors are not associated with well-formed ideas; rather, there is a feeling of physical tension resulting in an ameliorative action.

TABLE 10-1 Comparison of Tic Disorders Described in DSM-IV | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Freimer, revealed the following range of findings: approximately 0.1% to 1% of the population suffers from TS. The estimated prevalence of Chronic Tic Disorders is much higher ranging from 2% to 5%, and 10% to 15% of children during their school years. Boys are substantially more likely to suffer tics and TS, at 2 to 10 times the frequency of girls.

and cytokines and utilized diagnostic criteria for PANDAS outlined by Swedo and others. While this controversy continues, PANDAS should be considered in the following situations: DSM-IV diagnosis of a tic disorder or OCD; prepubertal onset; episodic presentation with abrupt onset and gradual spontaneous reduction of symptoms (“saw tooth” symptom pattern); subtle neurologic findings; choreiform movements, handwriting deterioration; GABHS infection temporally during symptom exacerbation. Further considerations in the differential diagnosis of tics are summarized in Table 10-2.

TABLE 10-2 Differential Diagnosis of Tics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

have tics or TS. Children with both disorders have a much greater risk of conduct disorder, depression, and overall dysfunction, than children with TS only. Children with TS and ADHD also suffer much higher rates of cognitive disturbances and learning disabilities (LD) than children with TS alone whose rates of LD approach normal controls.

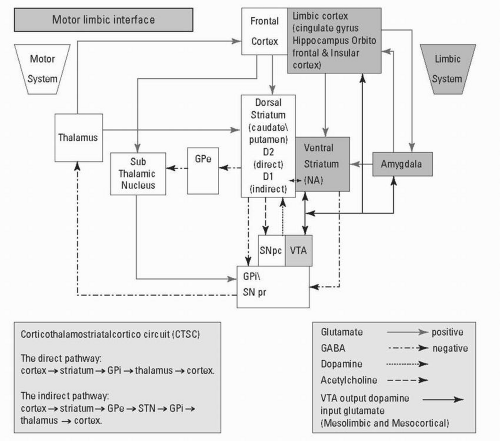

are believed to be central in causation and potential intervention. Cross activation of the limbic system may account for dysregulation of affect and control of rage in some patients, as well as the premonitory sensations and subjective experiences of tic episodes and interepisode states. Dysfunction in the striatum is also associated with the pathogenesis of OCD, ADHD, and an aspect of the neuropathology of Asperger syndrome (sensorimotor gating).

FIGURE 10-1. Schematic diagram of the motor-limbic interface. Note that these parallel systems converge in the striatum where motor and affective discharges are interactively modified. Proposed neuropathologic models of Tourette syndrome (TS) suggest anomalies in the functions of cortical and subcortical structures which function normally to modulate desired movement (voluntary cortical discharges), affect, and cognition. In TD, abnormalities in the complex cycling cascade of dopaminergic neuronal functions and influences are believed to be central in causation and potential intervention. Serotonin which is not represented here, has a modulatory role in CSTC circuits through limbic influence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|