, Jeffrey R. Strawn2 and Ernest V. Pedapati3

(1)

Division of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

(2)

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA

(3)

Division of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry Division of Child Neurology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

What Freud did not envision, however, is the extent to which useful theory has become relational.

—Robert N. Emde

Our efforts in this chapter will be to establish an essential foundation for the field of child and adolescent psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy, a model that has radically changed over the past 50 years, in order to anchor the remainder of this book in a two-person relational psychology model.

It is important to note that we do not intend to provide the reader with a complete review of all the contributors to child psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy. Rather, we will focus on those that have become the pillars of the traditional one-person psychology model and how their contributions helped influence the transition to a two-person relational psychology for the current child and adolescent psychiatrist and psychotherapist.

If the phrase “one-person psychology” does not initially appear puzzling, we would kindly ask the reader to reconsider. It is not lost on the authors the significance of calling any approach to psychodynamic psychotherapy “one person” as clearly there are, at minimum, two people involved in any psychotherapeutic process. Therefore, the concept of one-person psychology refers to the fact that the “one person” is the objective observer and not an active participant who shares his or her subjectivities with the patient during the interaction. Wachtel (2010) and Hoffman (1998) capture the one-person process as seeing the person in a fashion that assumes that the seer [psychotherapist] has no effect on the seen [patient]. Further, Wachtel notes that the distinction between one-person and two-person psychology is a useful beginning when considering that two-person relational psychology evolved from a traditional one-person psychology. As such, we define the concept of traditional one-person psychology as the psychodynamic clinical model in which the analyst’s or psychotherapist’s goal is to discover the patient’s unconscious conflicts that have hampered their ability to have a happy and successful life. One-person psychology model relies on the patient to transfer or displace early, unconscious unresolved conflicted wishes and feelings about their parents or caregivers to the analyst or psychotherapist. Therefore, in a traditional one-person model, transference is considered a critical element for psychotherapeutic change to occur in the form of insight. Pine (1988) proposed that the unifying principle of traditional one-person models was a psychoanalytic pluralism: “The psychologies of drive, ego, object relations, and self…. While the four certainly overlap, each adds something new to our theoretical understanding, and each has significant relevance in the clinical situation.”

2.1 Traditional One-Person Psychology

Child and adolescent psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy were developed under the umbrella of adult psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy and were modeled on traditional one-person psychology. The goals of treatment were uncovering the child’s unconscious inner life to elucidate the intrapsychic conflicts that created maladaptive patterns that led to a developmental interference in their emotional growth and the working through of their conflicts in order to achieve a healthier state.

Historically, fundamental psychoanalytic clinical concepts and treatments have been understood as one-person phenomena (Aron 1990). Therefore, in a traditional one-person model, transference is considered a critical element for psychotherapeutic change to occur. Transference was understood as a process occurring within the mind of the patient and not as an interpersonal event occurring between two people. Through the process of remembering and repeating past intrapsychic and unconscious conflicts, then transferring them onto the psychotherapist, the patient’s unhealthy ego defenses, in the form of resistances, can be “worked through.” The analyst or psychotherapist helps the patient identify what he or she needs to work through (i.e., unconscious conflicts and maladaptive defenses), which when brought to consciousness by the psychotherapist results in the patient developing insight and improving symptomatically (Freud 1914). Resnik (2004) summarizes, “The aim of analysis is self-knowledge largely achieved by the analysis and interpretation of defenses against the underlying impulses, drives, urges, fantasies and so on.” Freud’s “method” encouraged the use of neutrality, free association, dreams, and the psychoanalytic couch to facilitate transferences to develop. Freud believed that psychoanalysis had to be carried out in abstinence by the analyst (Freud 1914).

Traditional one-person psychology over the years collectively became what Pine (1988) described as psychoanalytic pluralism. Pine deftly states, “Psychoanalysis has produced what I shall refer to as ‘four psychologies’—the psychologies of drive, ego, object relations, and self. Each takes a somewhat different perspective on human psychological functioning, emphasizing somewhat different phenomena.”

Greenberg takes this a step further in defining this pluralism as “the widespread acknowledgment that a range of legitimately psychoanalytic points of view exists, whether or not there is any exchange of ideas among their adherents” (Greenberg 2012).

2.2 Historical Background of Traditional One-Person Model of Child and Adolescent Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

Child and adolescent psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy developed under the umbrella of adult psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. Most early child psychoanalytic and psychodynamic literature considered the psychological development of the child in distinct psychosexual phases based on Sigmund Freud’s drive theory: pre-oedipal, oedipal, latency, and adolescence. Herein, treatment was based on helping the child overcome the conflicts of the psychosexual stage they were unable to master, and then resuming their developmental trajectory.

Child and adolescent psychoanalysis is the treatment that relies in understanding the child and adolescents past unconscious inner life that influence his or her feelings, thoughts, and actions. The goal of child and adolescent psychoanalysis is the removal of symptoms and psychological roadblocks that interfere with normal development. Yanof (2005) reminds us that “for many years adult analysts questioned whether or not child analysis was ‘real’ analysis.” Child and adolescent psychodynamic psychotherapy is based on psychoanalytic principles and initially developed as an alternative method to those children who could adhere to the four to five times a week schedule, due to its regressive nature. Subsequently, child and adolescent psychodynamic psychotherapy became a form of treatment used by psychoanalytically trained clinicians.

In child psychoanalysis, the concept of transference was controversial. Anna Freud clarified the difficulties in the use of the concept of transference with children: “The adult tendency to repeat, which is important for creating transference, is complicated in the child by his hunger for new experience and new objects…” (1965). In spite of the differences, early child and adolescent psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy were firmly grounded on the principle tenets of one-person adult psychoanalysis.

To further illustrate the profound impact Freud’s work had in child and adolescent psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy over the last 100 years, we will first review his drive theories and then describe his classic first case of child psychoanalysis, Little Hans. We follow by comparing selected elements of Freud’s Little Hans case formulation with a perspective of a two-person relational psychotherapist. We next proceed to describe the influence some of his most esteemed contemporaries had to his drive-based theories and conclude with a description of ego psychology, object relations theory, and self-psychology in the context of their contributions to child psychoanalysis and child psychodynamic psychotherapy.

2.3 Freud and Classic Psychoanalytic Theories

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939): Drive Theory

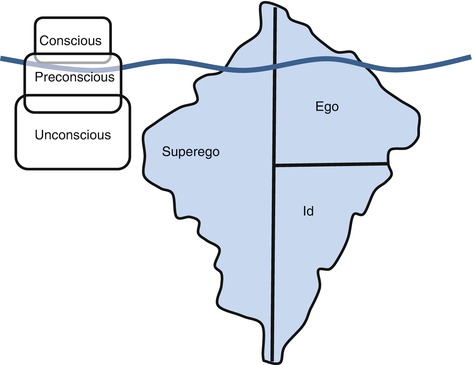

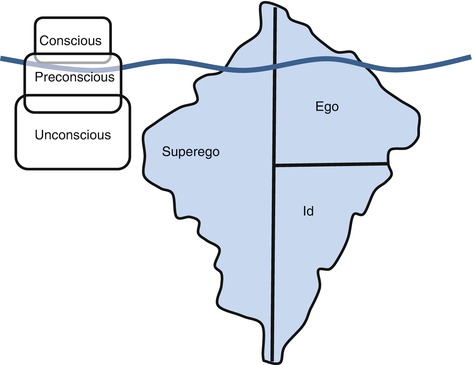

Classic psychoanalytic theory was developed by Sigmund Freud, who based his theories on his work with adult patients. In his efforts to understand the human mind, Freud proposed several hypotheses. First, the topographic model (Fig. 2.1) posits that most mental life occurs in the unconscious and that preconscious and conscious life is rather limited. Later, in revising the topographic model, Freud developed the structural model (Fig. 2.1). In this model the unconscious is comprised of several intrapsychic agencies: (1) the id , which embodies the instinctual sexual and aggressive drives and seeks for immediate gratification (Freud 1920); (2) the superego , which consists of the agency that seeks to obey cultural and societal norms incorporated into the person’s psyche; and (3) the ego , an agency that moderates the conflict between the id (which desires free reign) and the superego (which urges civility). Freud posited that the key developmental task of children involved “taming the instinctual drives” of the id through the development of the superego and ego (Freud 1916–1917).

Fig. 2.1

Sigmund Freud’s topographic (left) and structural (right) models of the mind

Still later, Freud wrote about the importance of the sexual drive theory in the form of psychosexual developmental stages determined by the organ of predominant interest to the infant/child for pleasure. As can be seen in Table 2.1, there are psychosexual stages of development —and each requires that conflicts from the previous phase be successfully resolved. For Freud, unresolved conflicts of the oral, anal, phallic, or oedipal phases led the person to have a neurotic fixation that, when he or she is under stress, causes an unconscious regression of the ego functions to behaviors of the stage fixated in. This is best exemplified when a 5-year-old child’s newly born sibling arrives home and the 5-year-old child demonstrates his anger at being displaced by the newborn by a regression to earlier anal level defenses (e.g., soiling himself or withholding bowel movements) which had been mastered prior to the arrival of the infant.

Table 2.1

Sigmund Freud’s psychosexual stages

Age | Oral | Anal | Phallic | Genital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

0–18 months | 19 months to 3 years | 3–4 years | 4–6 years | |

Erogenous zones | Mouth, tongue, lips, skin | Anus, rectum, abdomen | Genitals and urethra | Genitals |

Typical pleasurable activities | Sucking, licking, chewing, and biting | Bowel movements, elimination, and retention | Touching genitals, masturbation, urination | Loving toward parent of the opposite sex |

Developmental conflict | Needy or passive | Feelings of omnipotence (terrible twos), sadism | Castration anxiety | Oedipal (boys) and Electra complex (girls) |

Conflict resolution facilitated by psychotherapy | Curiosity, exploration | Autonomy, successful toilet training | Competence, identification with same-sex parent | Sexual identity |

Freud proposed that when the anxieties of the Oedipus complex are resolved, the person achieves the healthy psychological genital phase of normal heterosexuality (Freud 1924). According to Freud, pleasurable heterosexual intercourse was the goal of his psychosexual theories: “the subordination of all the component sexual instincts under the primacy of the genitals” (Freud 1905).

First Child in Psychoanalysis: Little Hans

Freud had encouraged his friends and colleagues to collect observations of the sexual life in their children to help him develop his theory of infantile sexuality (Freud 1909). In 1909, Freud wrote his famous case “Little Hans,” which is considered the first recorded psychoanalysis of a child. Little Hans’ father was a friend of Freud and a supporter of his theories. Although Freud did not conduct the analysis on the child, he helped Little Hans’ father conduct the analysis primarily through correspondence, although they met several times and Freud gave the father suggestions on how to approach the child.

Freud applied his psychoanalytic theories to the treatment of Little Hans, a 5-year-old boy who had developed a phobia to horses for fear that they would bite him or hurt his father. At 3 years old, Little Hans became interested in who in his family had or did not have a penis. By 3.5, his mother found him touching his penis and threatened him with castration if he continued to touch it (1909). Freud marked the mother’s castration threat as the episode that began Little Hans’ neurosis. Soon after the episode, the child was moved out from his parents’ bedroom, as his new sister arrived and was to take his place in the crib. After being moved, Little Hans took a special interest in comparing his body parts with his mother’s, his father’s, and animals’, wondering if they had a penis, a “wee-widdler.” Little Hans’ father tells Freud about the dialogue Hans had with his mother (1909):

While looking on intently at his mother undress, before going to bed:

“What are you staring like that for?” she asked.

Hans: “I was only looking to see if you’d got a widdler too.”

Mother: “Of course, Didn’t you know that?”

Hans: “No. I thought you were so big you’d have a widdler like a horse.”

Freud interprets the dialogue as representing the child’s Oedipus complex: fear that the father will punish him for desiring to have his mother and acting aggressively toward the father. Freud added that because Little Hans’ father was acting as the analyst, he was a real rival impeding the progress of the treatment. Little Hans continued to struggle with his phobia, and Freud requested that the child be brought to see him. Freud writes of this encounter:

I asked Hans jokingly whether his horses wore eyeglasses, to which he replied that they did not. I then asked him whether his father wore eyeglasses, to which, against all the evidence, he once more said no. Finally I asked him whether by “the black round the mouth” he meant a moustache; and I then disclosed to him that he was afraid of his father, precisely because he was so fond of his mother. It must be, I told him, that he thought his father was angry with him on that account; but this was not so, his father was fond of him in spite of it, and he might admit everything to him without any fear. Long before he was in the world, I went on, I had known that a little Hans would come who would be so fond of his mother that he would be bound to feel afraid of his father because of it; … “Does the Professor talk to God,” Hans asked his father on the way home, “as he can tell all that beforehand?” I should be extraordinarily proud of this recognition out of the mouth of a child, if I had not myself provoked it by my joking boastfulness. (1909)

Freud believed that the case of Little Hans confirmed his theory of infantile neurosis described in his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905) and remarked that he had learned nothing from the case that he had not already deduced from his analysis of adults.

We conclude with Freud’s comments regarding child psychoanalysis:

What? You have had small children in analysis? Children of less than six years? Can that be done? And is it not most risky for the children? … It can be done very well. It is hardly to be believed, what goes on in a child of four or five years old. Children are very active-minded at that age; their early sexual period is also a period of intellectual flowering. I have an impression that with the onset of the latency period they become mentally inhibited as well, stupider. (1926)

A Two-Person Relational Psychology View: Little Hans

In the case of Little Hans, several points are worth reviewing from a two-person relational perspective. First, we note that he had slept in his parents’ bedroom until the age of 3, when his sister arrived. It appears that from an attachment theory perspective, he seemed to be openly loved and had a great deal of exposure to his parent’s interactions, including morning dressing and evening undressing. From a contextual perspective, we do not have knowledge as to whether it was typical for children in Vienna during 1909 to sleep in the parental bedroom. We also note that Little Hans was a bright and verbal child who spoke often with his parents about his excitements and worries. One can hypothesize that he had an easy/flexible temperament and a secure attachment style (see Chaps. 5 and 8), reflected by frequent open dialogue with his parents and the trips he took to parks with his father. Finally, he had good cognitive flexibility (Chap. 8) demonstrated in his rich abstract reasoning: (1) He was aware of differences between female and male body parts, inquiring whether women can have a penis, and (2) he wondered about the size of horses as related to adult safety, fearing the horse could fall on top of his father. Herein, from a two-person relational model, it appears that Little Hans’ worries were occurring within the context of a normal developmental process of a child. Little Hans’ singular horse phobia may very well have been part of his healthy curiosity or clinically a simple phobia. We do not know if there were any other symptoms, and it appeared that he was adjusting quite well socially and academically. In fact, when Hans was 19 years old, he met with Freud and shared that after having read his case history, he could not remember the discussions with his father and did not recognize the events discussed in his case and shared that he was ostensibly doing well in life.

Considering that Little Hans may have been evaluated by a two-person relational psychotherapist, the treatment of choice would rely on here-and-now interactions between the patient and the active and present psychotherapist whose goal is to provide the patient a new emotional experience (see Chap. 5). Certainly the use of play would have been important to assess Little Hans’ capacity for social reciprocity and influence of the psychotherapist in the cocreated intersubjective field. The two-person relational psychotherapist relies on intersubjective experiences cocreated in vivo, influenced by each person’s internal working models of attachment developed during the first years of life and stored nonconsciously in nondeclarative memory systems (see Chap. 3). Additionally, in light of his fear of his father being hurt by a horse and his curiosity of whether others had a penis, it is reasonable that work with his parents would have provided a better contextual understanding of the complexities in the family system. The two-person relational approach is in contrast to a traditional one-person model which understands the patient’s symptoms as deriving primarily from conflicted internal experiences (e.g., fantasies, conflictual life), and attention to the external factors for some may be seen as a dilution of the psychoanalytic approach.

2.4 Freud’s Colleagues

While Freud is well known as the founding father of psychoanalysis, many of his contemporaries and followers also contributed to the field. Here we will introduce some of his most notable colleagues and protégés.

William Stekel (1868–1940)

William Stekel, one of Freud’s earliest followers, was once described as “Freud’s most distinguished pupil” (Wittels 1924). Stekel was an adult psychoanalyst, although he is recognized for being the first male psychoanalyst who worked psychoanalytically with children and adolescents. He claimed that parents and the environment in which children were raised were crucial to the development of a child’s psychological well-being (1931). Stekel believed that the psychoanalysis of children and adolescents was different from the psychoanalysis of adults, as it had to be adapted due to the child’s mobility and the importance in the use of play. According to Stekel, the analysis of children was not difficult because their neurotic symptoms disappeared more rapidly than in adults (Wittels 1924).

Stekel eventually dissented from Freud’s drive theory, which led to his expulsion from Freud’s inner circle and his later ostracism. Stekel may have been an early two-person relational psychoanalyst in that he believed that when the analyst took an active role as a real person in the psychoanalytic process, it helped the patient feel safe and understood (see Chap. 3).

Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961)

Although Carl Jung did not analyze children, he treated children in psychoanalytic psychotherapy as young as 6 years old and had an interest in the observation of infants. He had frequent communications with Freud about children’s emotional development and decided that women were best suited to practice child psychoanalysis due to their natural feminine intuition. He went on to provide child psychoanalytic courses to some of his female students who later became child psychoanalysts (Geissmann and Geissmann 1998).

Hermine von Hug-Hellmuth (1871–1924)

Hermine von Hug-Hellmuth was the first woman to apply psychoanalysis to the treatment of children. She was described as among Freud’s favorite students; her writings remain unknown to many current child psychotherapists (MacLean 1986). Although her work was limited to children over the age of 7, in 1912 Hug-Hellmuth published her seminal paper, The Analysis of a Dream of a 5–Year Old Boy (Drell 1982). Hug-Hellmuth was loyal to Freud’s psychoanalytic theories and was a strong advocate for the use of play in child psychoanalysis. She was an early proponent of children’s play being equivalent to free associations in adults, the royal road to the unconscious mind of children. She also believed that the goal of child psychoanalysis closely resembled the psychoanalysis of adults and that the transference neurosis of childhood was amenable to change through the interpretation of their symbolic play. Hug-Hellmuth was a teacher before she became a psychoanalyst, which helped her recognize the role parents had in their child’s neurosis and encouraged providing education to them in order to prevent from further conflicts in their child. Plastow (2011) states, “[Hug-Hellmuth’s] theory and practice heavily influenced the directions taken after her, in particular by Anna Freud and Melanie Klein, even if this influence is essentially unacknowledged by these authors.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree