Details regarding the symptoms preceding and following the event are critical to determining the cause for loss of consciousness (

8,

32,

35). A history regarding specific symptoms preceding loss of consciousness, particularly the duration and quality, should be elicited, and any triggering events should be identified (

Tables 7-1 and

7-2).

SEIZURES

Seizures generally present as stereotyped spells that follow a specific and consistent progression of symptoms during each event. In partial-onset seizures, a specific aura can occur before the onset of alteration in level of consciousness. A clue may be a specific aura occurring in isolation as well as at the onset of a complex partial seizure (those associated with alteration in level of consciousness but without generalization) or secondarily as a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. The duration of seizures is brief, generally less than 2 minutes. However, in seizures associated with an alteration in level of consciousness, patients often experience amnesia of the seizure itself and may not recall events immediately preceding or following the seizure. Postictal confusion can last for several minutes to hours.

FOCAL CEREBRAL ISCHEMIA

Focal cerebral ischemia resulting in transient alteration in level of consciousness is not common. Normal consciousness depends on the functioning of both cerebral hemispheres, the reticular formation, other upper brainstem structures, the thalamus, and the hypothalamus (

44). Thus, focal cerebral ischemia, as during a transient ischemic attack or stroke, must involve either both cerebral hemispheres or the brainstem and other deeper structures to result in alteration in level of consciousness. Posterior circulation ischemia or massive hemisphere infarction with shift can present with alteration in level of consciousness. Posterior circulation ischemia generally results in focal signs and symptoms (e.g., diplopia, eye movement abnormalities, other cranial nerve abnormalities, cerebellar dysfunction, motor and sensory dysfunction), which aid in the diagnosis. Massive infarction, of course, results in a sustained alteration in level of consciousness.

TRANSIENT GLOBAL AMNESIA

Transient global amnesia (TGA) presents with marked anterograde amnesia that generally persists for hours, as well as retrograde amnesia. Although patients may be disoriented to time and place, they retain knowledge of their identity. The patient often repeatedly asks the same questions and has difficulty encoding new memories during this event. No focal neurologic deficits are seen, and the patient is fully conscious throughout the episode, unlike during a complex partial seizure. The pathophysiology is debated but may be related to either cerebral ischemia or seizure. The finding of reversible changes in the CA-1 sector of the hippocampus on high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggests that this area may be involved in the pathophysiology of TGA (

6). The incidence of TGA has been estimated to be approximately five in 100,000 persons. Less than 25% of patients experience recurrent episodes (

2,

41).

SLEEP DISORDERS

Sleep disorders (e.g., sleep apnea or narcolepsy) present with other symptoms that suggest a sleep

disorder, particularly excessive daytime sleepiness, which results in lapses in consciousness. However, a history of sedation and concomitant symptoms (e.g., snoring or apnea) clearly differentiates the diagnosis of sleep disorders from other disorders.

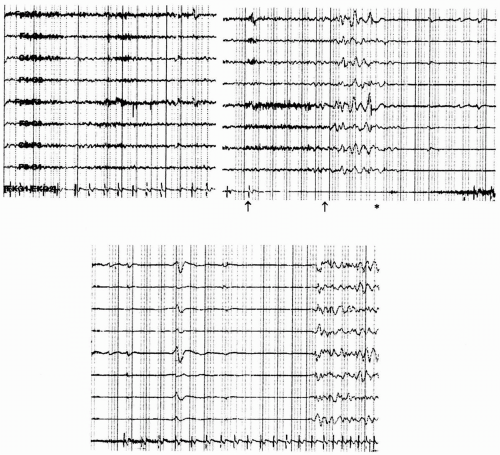

NONEPILEPTIC PSYCHOGENIC SEIZURES

Nonepileptic psychogenic seizures are more common in younger individuals; however, they also occur in the elderly. A variety of different types of presentations are seen. Although slumping and sudden apparent loss of consciousness can occur, shaking and other movements can occur as well. Common features include (a) nonstereotyped spells; (b) irregular, nonrhythmic movements; (c) eye closure during the event; (d) waxing and waning of symptoms; (e) prolonged symptoms over several minutes to hours; (f) no history of spells arising directly from sleep; and (g) no history of severe injury (e.g., fracture, burn) during the spells. The patient may have a history of sexual or physical abuse, lack of response to anticonvulsant medication, and history of a psychiatric disorder. Recent data suggest that, in the elderly, a history of severe physical health problems or health-related traumatic experiences may be a prominent risk factor in this age group (

20). Video-electroencephalographic (VEEG) monitoring (

1) or EEG and observation of the episode are helpful in establishing the diagnosis.

SYNCOPE

Because syncope has a myriad of etiologies, it is useful to classify its causes into (a) cardiovascular, (b) neurally mediated (reflexogenic), (c) orthostatic (postural), and (d) metabolic because the diagnostic evaluation and prognosis in each category differ. Cardiovascular causes of syncope include arrhythmias and structural cardiopulmonary disease, and they should be considered in any elderly patient with significant heart disease (e.g., myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure). Arrhythmic syncope is often abrupt, and such an episode in a patient with left ventricular dysfunction or conduction abnormalities (e.g., bundle branch block) should raise suspicion for ventricular tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias, respectively. Structural cardiopulmonary disease causing syncope reduces cerebral perfusion by obstructing blood flow (e.g., aortic stenosis, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy) or decreasing cardiac output (e.g., myocardial infarction, tamponade).

Neurally mediated syncope includes vasovagal, viscerovagal (situational), and carotid sinus hypersensitivity and is due to an exaggerated reflex that increases vagal tone (causing bradycardia) while reducing sympathetic outflow (causing hypotension). Such forms of syncope often have a triggering event (e.g., prolonged standing, defecation, coughing). The classical prodromal symptoms of vasovagal syncope (warmth, nausea, lightheadedness, and diaphoresis) might be absent in

an elderly patient. Abrupt syncope without prodrome can even occur (malignant vasovagal syncope). Orthostatic syncope is due to an abrupt drop in blood pressure while assuming an erect posture and is common in the elderly (

54). Autonomic dysfunction, loss of baroreceptor responses, and frequent use of multiple medications predispose elderly individuals to orthostatic syncope. Primary autonomic failure can be caused by multiple system atrophy, which is generally associated with brainstem dysfunction or parkinsonism. The Shy-Drager and Bradbury-Eggleston types of autonomic failure are associated with other evidence of autonomic dysfunction, including sexual and bladder dysfunction and anhidrosis. Secondary autonomic dysfunction can result from an autonomic neuropathy, often associated with a peripheral neuropathy, which may be seen in diabetes mellitus, chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy, amyloidosis, and other types of neuropathy. Metabolic abnormalities causing syncope are rare. These include high-altitude sickness [causing low partial pressure of oxygen (PO2)], acute hyperventilation [causing low partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) and cerebral vasoconstriction], and hypoglycemia. Insulinomas can cause repetitive seizurelike spells due to recurrent hypoglycemia (

7). Hypoglycemia is also often associated with neuro-adrenergic symptoms (e.g., diaphoresis and tremors).