Lesion

Overall endocrinopathy

Diabetes insipidus

Panhypopituitarism

Craniopharyngioma

56–83 %

4–37 %

24–42 %

Rathke’s cleft cyst

66–70 %

0–13 %

0–11 %

Arachnoid cyst

50–60 %

Case reports

Case reports

Tuberculum sella meningioma

2–39 %

4.5 %

4.5 %

Chordoma

Case reports

Insufficient data

Insufficient data

Metastases/Lymphoma

23–100 %

45–100 %

23–25 %

Following surgical resection of non-adenomatous sellar lesions, anterior pituitary gland function can improve, as is commonly seen with Rathke’s cleft cysts and sellar arachnoid cysts. However, it is extremely uncommon for diabetes insipidus to resolve post-operatively (Table 21.2). New post-operative anterior and/or posterior gland dysfunction is most commonly seen with craniopharyngiomas and occasionally with Rathke’s cleft cysts (particularly supraglandular cysts adherent to the infundibulum), but rarely with parasellar meningiomas and clival chordomas. The relevant surgical anatomy and imaging, surgical nuances for preserving gland function and hormonal outcomes for each of these lesion types is discussed below.

Table 21.2

Post-operative pituitary outcome

Lesion | New anterior pituitary dysfunction | New diabetes insipidus | Improvement of pre-operative pituitary dysfunction |

|---|---|---|---|

Craniopharyngioma | 17–80 % | 23–69 % | 0–35 % |

Rathke’s cleft cyst | 1.7–6 % | 2–19 % | 22–41 % |

Arachnoid cyst | 0 % | 0 % | 25–100 % |

Tuberculum sella meningioma | 0–23 % | 0 % | 0 % |

Chordoma | Case reports | Case reports | Insufficient data |

Metastases/Lymphoma | Insufficient data | Insufficient data | Insufficient data |

Endonasal Transsphenoidal Approach with Attention to Gland Identification and Preservation

The endonasal transsphenoidal approach, enhanced with neuroendoscopy, offers a safe surgical trajectory for the great majority of parasellar lesions. In terms of preserving gland function, a careful review of the preoperative sellar MRI allows one to anticipate gland location and the course of the infundibulum relative to the tumor. While most pituitary adenomas distort the gland by pushing it laterally, posteriorly and or superiorly, non-adenomatous lesions can push the gland anteriorly (as is often the case with Rathke’s cleft cysts and sellar arachnoid cysts) or inferiorly (as is often the case with craniopharyngiomas and tuberculum sella and dorsum sellae meningiomas). While craniopharyngiomas are the most variable in their location, they are the tumor that most commonly engulfs the infundibulum and extends into the retro-chiasmal space.

In patients with fully or partially intact pituitary gland function, in whom functional preservation is a goal, the gland should be gently manipulated. To access a tumor or cyst behind the gland, it is generally safe to make a low vertical gland incision and even to remove a small window of attenuated gland as a working corridor (Dusick et al. 2008, Table). This approach is preferred over putting excessive traction on the gland which can compromise gland and infundibulum neurovasculature. An alternative and technically more demanding approach for working in the retro-glandular space is pituitary gland transposition as described by Kassam et al. (2008) for some lesions such as craniopharyngiomas, chordomas and meningiomas. For lesions that extend into the suprasellar and supra-diaphragmatic space, particularly for retrochisamal craniopharyngiomas and tuberculum sellae meningiomas, it is also critical to visualize and preserve the superior hypophyseal arteries which typically course from laterally to medially to the infundibulum in 2 or 3 branches and then bifurcate superiorly to the undersurface of the chiasm and inferiorly to the gland . Injury to these delicate arteries can contribute to gland dysfunction as well as visual field loss from chiasmal ischemia (Kassam et al. 2008).

Specific Sellar Lesions: Approach and Hormonal Outcomes

Craniopharyngioma

Relevant Anatomy and Imaging: Craniopha-ryngiomas typically have their epicenter around the infundibulum but can extend into various locations including intrasellar, suprasellar, intraventricular, or a combination of these areas as well as into the frontal and middle fossas. However, the most common location for craniopharyngiomas is in the sellar, suprasellar and retrochiasmal space.

Clinical Presentation and Hormonal Outcomes: In addition to the common presentation of visual loss and headaches, craniopharyngiomas lead to pituitary hormonal dysfunction in 56–83 % of patients. The most common hypothalamic pituitary axes affected are the gonadotrope and somatotrope systems. The incidence of panhypopituitarism is approximately 24–42 %. Diabetes insipidus is a less common presenting finding (4–37 %) (Honegger et al. 1999, Table; Shin et al. 1999, Table). Following surgery, the incidence of new panhypopituitarism is 17–80 %. This is dependent on the tumor location, the surgical approach, the degree of tumor resection, and the preservation of the normal pituitary gland and infundibulum. The incidence of post-operative prolonged diabetes insipidus is 23–69 % (Honegger et al. 1999; Shin et al. 1999). With more extensive tumors involving the hypothalamus, the incidence of adipsic DI, temperature dysregulation and hypothalamic obesity can occur. These syndromes are very difficult to manage as the thirst and satiety nuclei of the hypothalamus are affected and hormone replacement alone does not suffice (Crowley et al. 2010). With tumors that significantly involve the infundibulum, deliberate pituitary stalk sectioning may be necessary, resulting in DI and pan-hypopituitarism. In tumors where there is apparent anatomic preservation of the pituitary gland, the incidence of pituitary dysfunction remains elevated regardless of surgical approach (Honegger et al. 1999). Even with stalk preservation, post-operative DI still occurs in 52–64 % of patients. Post-operative hypocortisolism occurs in up to 40 % of patients.

Surgical Nuances for Maximizing Gland Preservation: Given that the majority of craniopharyngiomas are in the sellar, suprasellar and retrochiasmal space, an endonasal transsphenoidal approach with endoscopy or endoscopic assistance is recommended for the majority of such tumors. In some tumors with predominantly pre-chiasmal or lateral suprasellar extensions, the supraorbital or pterional approach may be preferred (Fatemi et al. 2009). For lesions predominantly within the third ventricle, a trans-ventricular approach may be utilized.

If preoperative pituitary gland function is largely intact, an attempt is made to identify the pituitary stalk and its site of insertion to the pituitary gland early in the dissection and to avoid traction on the stalk during tumor removal. However, when pre-operative diabetes insipidus or multiple anterior gland deficiencies are present and/or the pituitary stalk is engulfed by tumor on the pre-operative MRI, persevering gland function is less likely and thus less of a priority although an effort should be made in every case to identify and preserve the infundibulum. While total resection of craniopharyngiomas has been advocated by some, it is associated with a higher morbidity and mortality (Zhou and Shi 2004). Consequently, the goal should be safe maximal resection and settling for subtotal removal if dense adhesions to neurovascular structures are present (Puget et al. 2007; Van Effenterre and Boch 2002). In recent reports, total removal rates have ranged from 7 % to 89 % in transsphenoidal series with the microscope and/or endoscope (Chakrabarti et al. 2005; Czirjak and Szeifert 2006; Laws et al. 2005), 40–74 % in supra-orbital series (Czirjak and Szeifert 2006; Jallo et al. 2005) and 6–100 % by the subfrontal or pterional routes (Fahlbusch and Schott 2002, Table; Puget et al. 2007; Van Effenterre and Boch 2002).

Rathke’s Cleft Cyst

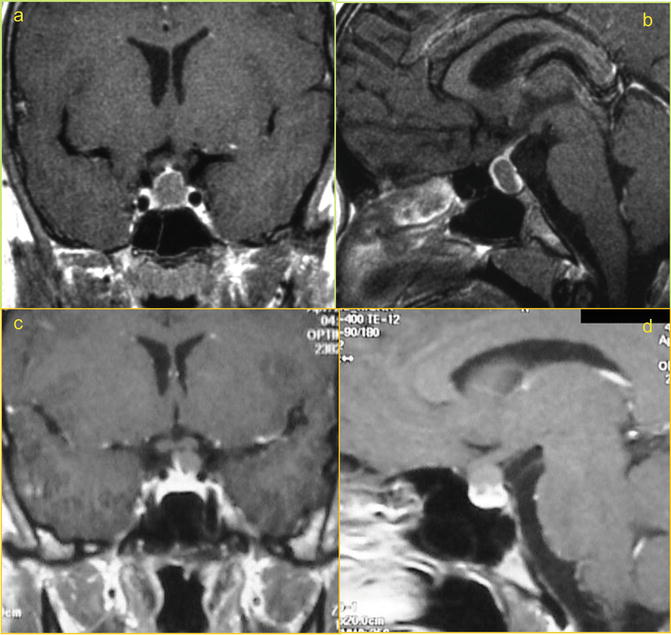

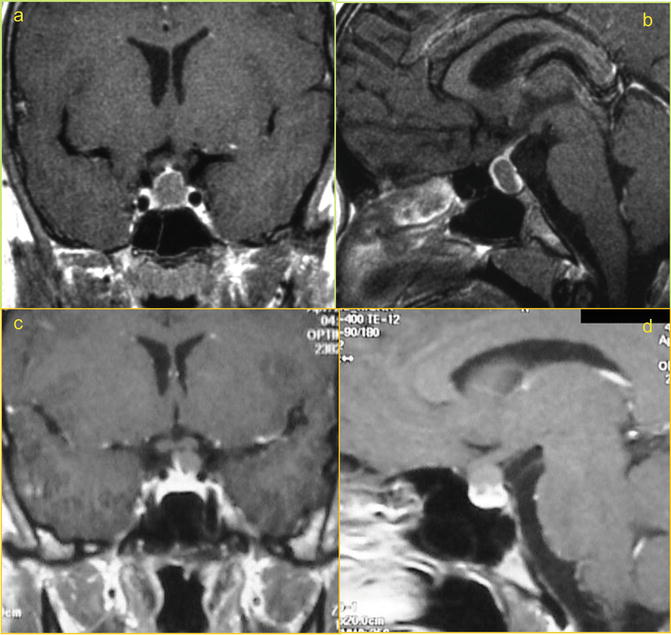

Relevant Anatomy and Imaging: Rathke’s cleft cysts are the most common non-adenomatous symptomatic lesions affecting the pituitary gland (Dusick et al. 2005, Table). They most commonly are intrasellar with or without suprasellar extension causing anterior displacement of the anterior gland and posterior displacement of the posterior lobe. Less commonly they can be entirely supraglandular in location often adherent to infundibulum and extending into the suprasellar space (Potts et al. 2011) (Fig. 21.1).

Fig. 21.1

Coronal and Sagittal MRI post-contrast images of Intrasellar (a, b) and supraglandular (c, d) Rathke’s Cleft Cyst

Clinical Presentation and Hormonal Outcomes: These lesions are most commonly associated with headaches (70–85 %), typically frontal or retro-orbital in location. Hypopituitarism can also occur, though more frequent in children (Aho et al. 2005, Table; Madhok et al. 2010, Table; Potts et al. 2011, Table). In a large series of symptomatic patients with RCC, pituitary dysfunction was present in 66–70 % of patients, with 0–13 % presenting with DI (Aho et al. 2005). Pre-operative anterior hormonal deficits frequently improve as shown in our recent report with a 41 % rate of resolved anterior axis deficiencies and a 67 % rate of resolved stalk hyperprolactinemia (Dusick et al. 2008). Resolution of diabetes insipidus however is extremely rare (Frank et al. 2005).

Surgical Nuances for Maximizing Gland Preservation: For intrasellar RCCs, since such cysts are typically located behind the anterior lobe, their removal involves an approach through the anterior gland via a low midline vertical glandular incision or as described by Madhok et al. (2010) using an infrasellar approach to the cyst contents with minimal gland incision. Through this small low anterior or inferior corridor, the cyst contents are removed with suction, curettes and irrigation. Given that the resection cavity is generally formed by the anterior and posterior pituitary lobes and the cyst lining is generally adherent to these normal structures no attempt should be made to vigorously strip the cyst wall off of the normal gland, since this approach has been associated with a higher rate of post-operative pituitary gland dysfunction including diabetes insipidus (Aho et al. 2005). However, this less aggressive approach is also associated with a higher rate of cyst recurrence (Kim et al. 2004). A detailed endoscopic visualization of the cyst wall and normal pituitary structures may improve surgical outcomes and decrease the incidence of DI. Although occasionally utilized, instilling caustic agents such as ethanol or hydrogen peroxide does not appear to decrease the recurrence rate of these cysts, and may increase pituitary gland dysfunction (Benveniste et al. 2004).

Sellar Arachnoid Cysts

Relevant Anatomy and Imaging: Arachnoid cysts of the sellar and parasellar region are generally thought to be congenital and/or developmental in origin. Pre-operative imaging demonstrates a cyst with signal characteristics similar to CSF (hyperintense on T2, hypointense on T1, no diffusion restriction on DWI). Unlike sellar Rathke’s cleft cysts which consistently reside between the anterior and posterior lobes of the pituitary, sellar arachnoid cysts have a much more variable relationship to the gland and infundibulum. The gland may be pushed anteriorly or splayed bilaterally, superiorly or posteriorly by the cyst (McLaughlin et al. 2012, Table).

Clinical Presentation and Hormonal Outcomes: Pre-operative anterior pituitary dysfunction can be seen with sellar arachnoid cysts ranging from 50–60 % (Shin et al. 1999), while DI is rarely seen (McLaughlin et al. 2012). Following surgical fenestration and cyst obliteration occlusion, pituitary dysfunction can improve in 0–100 % of patients, being rare to improve in those presenting with panhypopituitarism and common to improve in those with partial deficiencies (Table 21.2).

Surgical Nuances for Maximizing Gland Preservation: As we recently described, our technique for sellar arachnoid cyst obliteration involves a relatively small dural opening and cyst cavity obliteration with an abdominal fat graft and sellar floor reconstruction (McLaughlin et al. 2012). The dural opening should be large enough to pass a 4 mm rigid endoscope but not so large as to increase the complexity of the skull base closure. The anterior arachnoid cyst membrane is opened sharply with a microblade with return of clear cerebrospinal fluid. An inspection of the AC cavity is performed making sure the lesion is not a cystic tumor, and looking for potential diaphragmatic defects or arachnoid diverticula. Widening or dissection through the diaphragmatic defect in order to establish a larger communication to the suprasellar SAS is specifically avoided. Additionally, the cyst wall is not dissected off of the pituitary gland which is typically thinned and attenuated, given the risk of worsening pituitary dysfunction. Subsequently, the defect is obliterated with a fat graft that has enough volume to fill the cavity without excess pressure on the surrounding normal pituitary gland which is typically thinned. The fat graft is supported with a buttress, collagen sponges, and tissue glue.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree