Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

11.1 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder

11.1 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder

Both posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and acute stress disorder are marked by increased stress and anxiety following exposure to a traumatic or stressful event. Traumatic or stressful events may include being a witness to or being involved in a violent accident or crime, military combat, or assault, being kidnapped, being involved in a natural disaster, being diagnosed with a life-threatening illness, or experiencing systematic physical or sexual abuse. The person reacts to the experience with fear and helplessness, persistently relives the event, and tries to avoid being reminded of it. The event may be relived in dreams and waking thoughts (flashbacks).

The stressors causing both acute stress disorder and PTSD are sufficiently overwhelming to affect almost everyone. They can arise from experiences in war, torture (discussed in detail below), natural catastrophes, assault, rape, and serious accidents, for example, in cars and in burning buildings. Persons reexperience the traumatic event in their dreams and their daily thoughts; they are determined to avoid anything that brings the event to mind and they undergo a numbing of responsiveness along with a state of hyperarousal. Other symptoms are depression, anxiety, and cognitive difficulties such as poor concentration.

A link between acute mental syndromes and traumatic events has been recognized for more than 200 years. Observations of trauma-related syndromes were documented following the Civil War, and early psychoanalytic writers, including Sigmund Freud, noted a relation between neurosis and trauma. Considerable interest in posttraumatic mental disorders was stimulated by observations of “battle fatigue,” “shell shock,” and “soldier’s heart” in both World Wars I and II. Moreover, increasing documentation of mental reactions to the Holocaust, to a series of natural disasters, and to assault contributed to the growing recognition of a close relation between trauma and psychopathology.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The lifetime incidence of PTSD is estimated to be 9 to 15 percent and the lifetime prevalence of PTSD is estimated to be about 8 percent of the general population, although an additional 5 to 15 percent may experience subclinical forms of the disorder. The lifetime prevalence rate is 10 percent in women and 4 percent in men. According to the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS), 30 percent of men develop full-blown PTSD after having served in the war and an additional 22.5 percent develop partial PTSD, falling just short of qualifying for the disorder. Among veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, 13 percent received the diagnosis of PTSD.

Although PTSD can appear at any age, it is most prevalent in young adults, because they tend to be more exposed to precipitating situations. Children can also have the disorder (see Section 31.11b). Men and women differ in the types of traumas to which they are exposed. Historically, men’s trauma was usually combat experience, and women’s trauma was most commonly assault or rape. The disorder is most likely to occur in those who are single, divorced, widowed, socially withdrawn, or of low socioeconomic level, but anyone can be effected, no one is immune. The most important risk factors, however, for this disorder are the severity, duration, and proximity of a person’s exposure to the actual trauma. A familial pattern seems to exist for this disorder, and first-degree biological relatives of persons with a history of depression have an increased risk for developing PTSD following a traumatic event.

COMORBIDITY

Comorbidity rates are high among patients with PTSD, with about two thirds having at least two other disorders. Common comorbid conditions include depressive disorders, substance-related disorders, anxiety disorders, and bipolar disorders. Comorbid disorders make persons more vulnerable to develop PTSD.

ETIOLOGY

Stressor

By definition, a stressor is the prime causative factor in the development of PTSD. Not everyone experiences the disorder after a traumatic event, however. The stressor alone does not suffice to cause the disorder. Clinicians must also consider individual’s preexisting biological and psychosocial factors and events that happened before and after the trauma. For example, a member of a group who lived through a disaster can sometimes better deal with trauma because others have also shared the experience. The stressor’s subjective meaning to a person is also important. For example, survivors of a catastrophe may experience guilt feelings (survivor guilt) that can predispose to, or exacerbate, PTSD.

Three weeks after a train derailment, a 42-year-old budget analyst presented to the mental health clinic. He noted that he was embarrassed to seek care, as he was previously a firefighter, but he felt he needed “some reassurance that what I’m experiencing is normal.” He reported that, since the wreck, he had been feeling nervous and on edge. He experienced some difficulty focusing his attention at work, and he had occasional intrusive recollections of “the way the ground just shook; the tremendous ‘bang’ and then the screaming when the train rolled over.” He noted that he had spoken with five business colleagues who were also on the train, and three acknowledged similar symptoms. However, they said that they were improving. He was more concerned about the frequency of tearful episodes, sometimes brought on by hearing the name of a severely injured friend, but, at other times, occurring “for no particular reason.” In addition, he noted that, when he evacuated the train, rescue workers gave him explicit directions about where to report, and, although he complied, he now felt extremely guilty about not returning to the train to assist in the rescue of others. He reported a modest decrease in appetite and denied weight loss but noted that he had stopped jogging during his lunch break. He had difficulty initiating sleep, so he had begun consuming a “glass or two” of wine before bed to help with this. He did not feel rested on awakening. He denied suicidal ideation or any psychotic symptoms. His sister had taken an antidepressant several years ago, but he did not desire medication. He feared that side effects could further diminish his ability to function at the workplace and could cause him to gain weight. (Courtesy of D. M. Benedek, M.D., R. J. Ursano, M.D., and H. C. Holloway, M.D.)

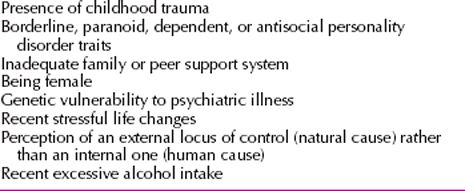

Risk Factors

Even when faced with overwhelming trauma, most persons do not experience PTSD symptoms. The National Comorbidity Study found that 60 percent of males and 50 percent of females had experienced some significant trauma, whereas the reported lifetime prevalence of PTSD, as mentioned earlier, was only about 8 percent. Similarly, events that may appear mundane or less than catastrophic to most persons can produce PTSD in some. Evidence indicates of a dose–response relationship between the degree of trauma and the likelihood of symptoms. Table 11.1-1 summarizes vulnerability factors that appear to play etiological roles in the disorder.

Table 11.1-1

Table 11.1-1

Predisposing Vulnerability Factors in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

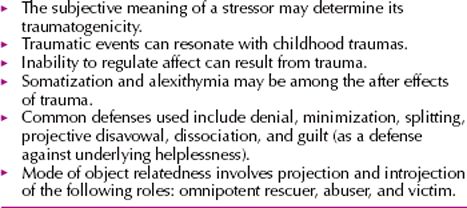

Psychodynamic Factors

The psychoanalytic model of the PTSD hypothesizes that the trauma has reactivated a previously quiescent, yet unresolved psychological conflict. The revival of the childhood trauma results in regression and the use of the defense mechanisms of repression, denial, reaction formation, and undoing. According to Freud, a splitting of consciousness occurs in patients who reported a history of childhood sexual trauma. A preexisting conflict might be symbolically reawakened by the new traumatic event. The ego relives and thereby tries to master and reduce the anxiety. Psychodynamic themes in PTSD are summarized in Table 11.1-2. Persons who suffer from alexithymia, the inability to identify or verbalize feeling states, are incapable of soothing themselves when under stress.

Table 11.1-2

Table 11.1-2

Psychodynamic Themes in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Cognitive-Behavioral Factors

The cognitive model of PTSD posits that affected persons cannot process or rationalize the trauma that precipitated the disorder. They continue to experience the stress and attempt to avoid experiencing it by avoidance techniques. Consistent with their partial ability to cope cognitively with the event, persons experience alternating periods of acknowledging and blocking the event. The attempt of the brain to process the massive amount of information provoked by the trauma is thought to produce these alternating periods. The behavioral model of PTSD emphasizes two phases in its development. First, the trauma (the unconditioned stimulus) that produces a fear response is paired, through classic conditioning, with a conditioned stimulus (physical or mental reminders of the trauma, such as sights, smells, or sounds). Second, through instrumental learning, the conditioned stimuli elicit the fear response independent of the original unconditioned stimulus, and persons develop a pattern of avoiding both the conditioned stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus. Some persons also receive secondary gains from the external world, commonly monetary compensation, increased attention or sympathy, and the satisfaction of dependency needs. These gains reinforce the disorder and its persistence.

Biological Factors

The biological theories of PTSD have developed both from preclinical studies of animal models of stress and from measures of biological variables in clinical populations with the disorder. Many neurotransmitter systems have been implicated by both sets of data. Preclinical models of learned helplessness, kindling, and sensitization in animals have led to theories about norepinephrine, dopamine, endogenous opioids, and benzodiazepine receptors and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. In clinical populations, data have supported hypotheses that the noradrenergic and endogenous opiate systems, as well as the HPA axis, are hyperactive in at least some patients with PTSD. Other major biological findings are increased activity and responsiveness of the autonomic nervous system, as evidenced by elevated heart rates and blood pressure readings and by abnormal sleep architecture (e.g., sleep fragmentation and increased sleep latency). Some researchers have suggested a similarity between PTSD and two other psychiatric disorders: major depressive disorder and panic disorder.

Noradrenergic System. Soldiers with PTSD-like symptoms exhibit nervousness, increased blood pressure and heart rate, palpitations, sweating, flushing, and tremors—symptoms associated with adrenergic drugs. Studies found increased 24-hour urine epinephrine concentrations in veterans with PTSD and increased urine catecholamine concentrations in sexually abused girls. Further, platelet α2– and lymphocyte β-adrenergic receptors are downregulated in PTSD, possibly in response to chronically elevated catecholamine concentrations. About 30 to 40 percent of patients with PTSD report flashbacks after yohimbine (Yocon) administration. Such findings are strong evidence for altered function in the noradrenergic system in PTSD.

Opioid System. Abnormality in the opioid system is suggested by low plasma β-endorphin concentrations in PTSD. Combat veterans with PTSD demonstrate a naloxone (Narcan)-reversible analgesic response to combat-related stimuli, raising the possibility of opioid system hyperregulation similar to that in the HPA axis. One study showed that nalmefene (Revex), an opioid receptor antagonist, was of use in reducing symptoms of PTSD in combat veterans.

Corticotropin-Releasing Factor and the HPA Axis. Several factors point to dysfunction of the HPA axis. Studies have demonstrated low plasma and urinary free cortisol concentrations in PTSD. More glucocorticoid receptors are found on lymphocytes, and challenge with exogenous corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) yields a blunted corticotropin (ACTH) response. Further, suppression of cortisol by challenge with low-dose dexamethasone (Decadron) is enhanced in PTSD. This indicates hyperregulation of the HPA axis in PTSD. Also, some studies have revealed cortisol hypersuppression in trauma-exposed patients who develop PTSD, compared with patients exposed to trauma who do not develop PTSD, indicating that it might be specifically associated with PTSD and not just trauma. Overall, this hyperregulation of the HPA axis differs from the neuroendocrine activity usually seen during stress and in other disorders such as depression. Recently, the role of the hippocampus in PTSD has received increased attention, although the issue remains controversial. Animal studies have shown that stress is associated with structural changes in the hippocampus, and studies of combat veterans with PTSD have revealed a lower average volume in the hippocampal region of the brain. Structural changes in the amygdala, an area of the brain associated with fear, have also been demonstrated.

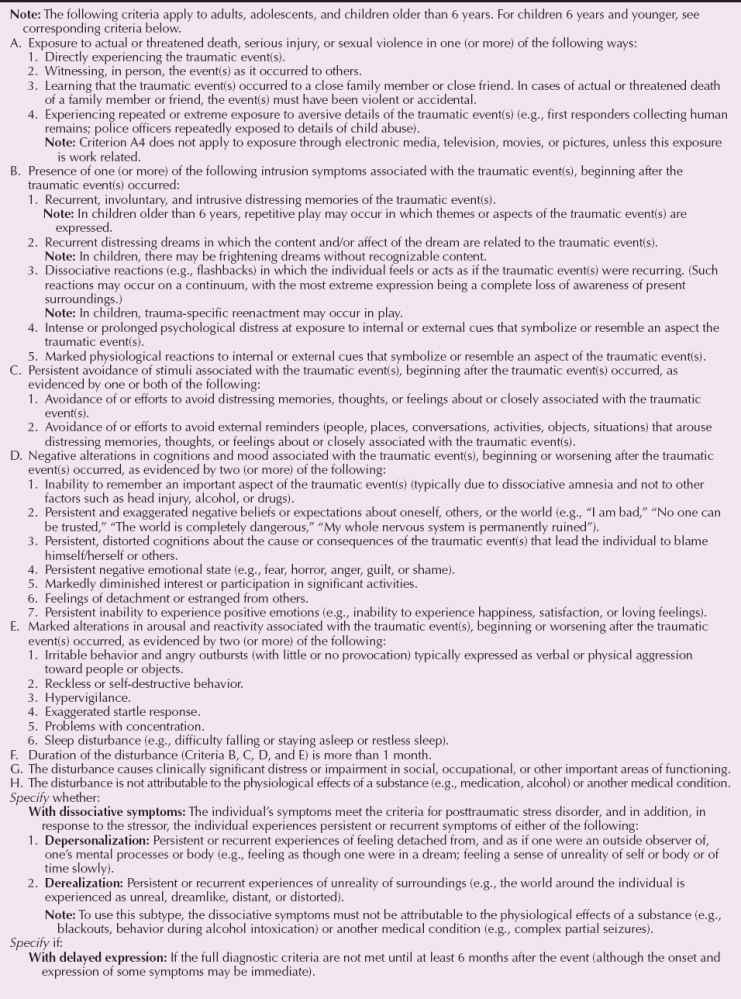

DIAGNOSIS

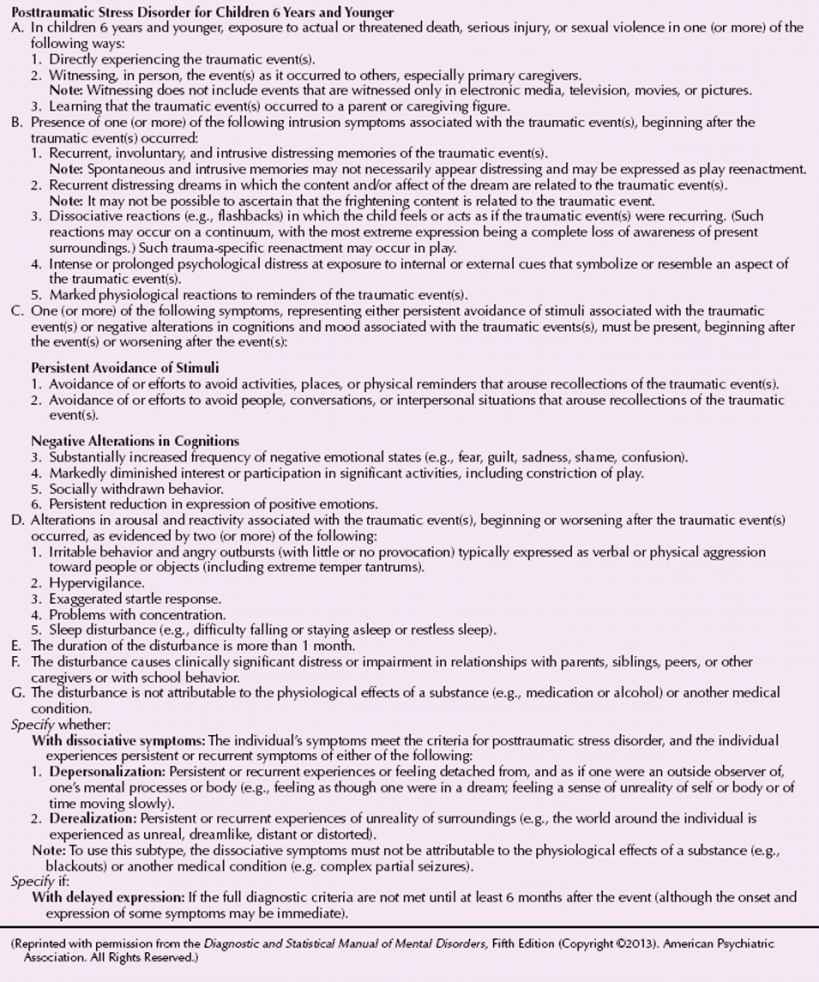

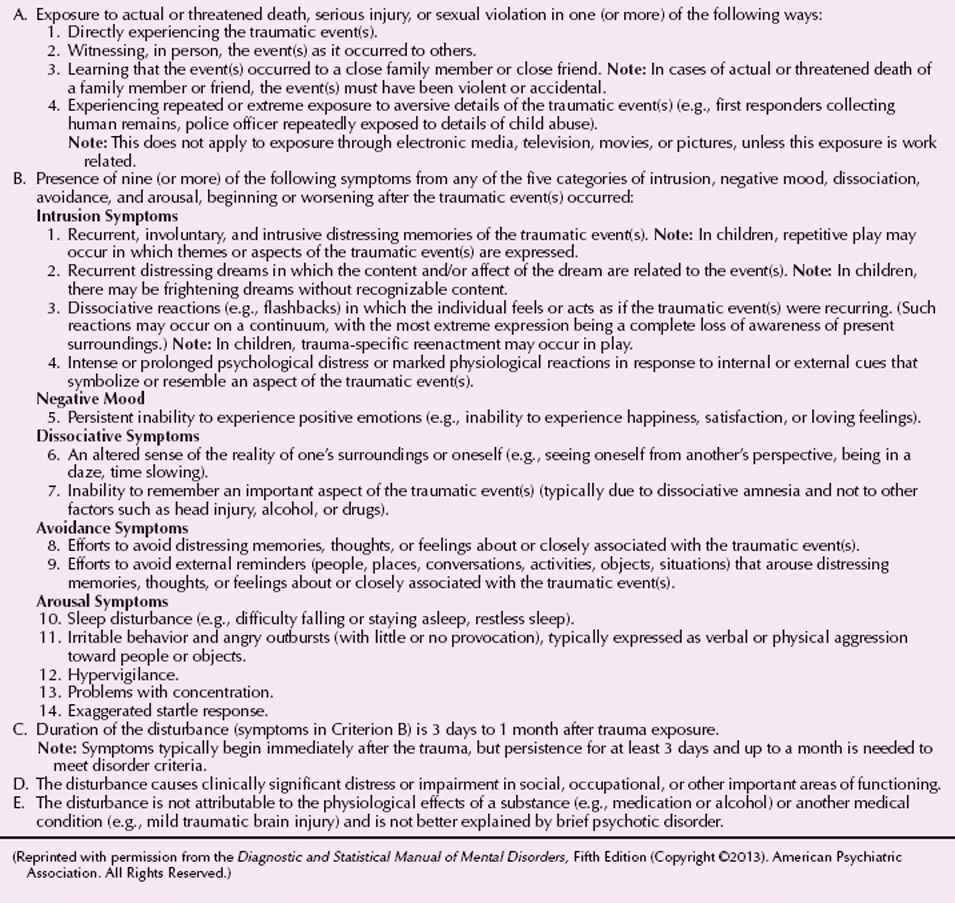

The 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria for PTSD (Table 11.1-3) specify that the symptoms of intrusion, avoidance, alternations of mood and cognition, and hyperarousal must have lasted more than 1 month. The DSM-5 diagnosis of PTSD allows the physician to specify if the symptoms occur in preschool-aged children or with dissociative (depersonalization/derealization) symptoms. For patients whose symptoms have been present less than 1 month, the appropriate diagnosis may be acute stress disorder (Table 11.1-4).

Table 11.1-3

Table 11.1-3

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Table 11.1-4

Table 11.1-4

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Acute Stress Disorder

Mrs. M sought treatment for symptoms that she developed in the wake of an assault that had occurred about 6 weeks prior to her psychiatric evaluation. While leaving work late one evening, Mrs. M was attacked in a parking lot next to the hospital in which she worked. She was raped and badly beaten but was able to escape and call for help. On referral, Mrs. M reported frequent intrusive thoughts about the assault, including nightmares about the event and recurrent intrusive visions of her assailant. She reported that she now took the bus to work to avoid the scene of the attack and that she had to change her work hours so that she did not have to leave the building after dark. In addition, she reported that she had difficulty interacting with men, particularly those who resembled her attacker, and that she consequently avoided such interactions whenever possible. Mrs. M described increased irritability, difficulty staying asleep at night, poor concentration, and an increased focus on her environment, particularly after dark. (Courtesy of Erin B. McClure-Tone, Ph.D., and Daniel S. Pine, M.D.)

CLINICAL FEATURES

Individuals with PTSD show symptoms in three domains: intrusion symptoms following the trauma, avoiding stimuli associated with the trauma, and experiencing symptoms of increased automatic arousal, such as an enhanced startle. Flashbacks, in which the individual may act and feel as if the trauma were reoccurring, represent a classic intrusion symptom. Other intrusion symptoms include distressing recollections or dreams and either physiological or psychological stress reactions to exposure to stimuli that are linked to the trauma. An individual must exhibit at least one intrusion symptom to meet the criteria for PTSD. Symptoms of avoidance associated with PTSD include efforts to avoid thoughts or activities related to the trauma, anhedonia, reduced capacity to remember events related to the trauma, blunted affect, feelings of detachment or derealization, and a sense of a foreshortened future. Symptoms of increased arousal include insomnia, irritability, hypervigilance, and exaggerated startle.

A 40-year-old man watched the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack on the World Trade Center on television. Immediately thereafter he developed feelings of panic associated with thoughts that he was going to die. The panic disappeared within a few hours; however, for the next few nights he had nightmares with obsessive thoughts about dying. He sought consultation and reported to the psychiatrist that his wife had been killed in a plane crash 20 years earlier. He described having adapted to the loss “normally” and was aware that his current symptoms were probably related to that traumatic event. On further exploration in brief psychotherapy, he realized that his reactions to his wife’s death were muted and that his relationship with her was ambivalent. At the time of her death, he was contemplating divorce and frequently had wished her dead. He had never fully worked through the mourning process for his wife, and his catastrophic reaction to the terrorist attack was related, in part, to those suppressed feelings. He was able to recognize his feelings of guilt related to his wife and his need for punishment manifested by thinking he was going to die.

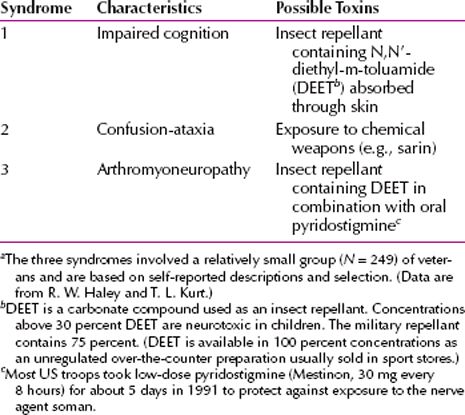

Gulf War Syndrome

In the Persian Gulf War against Iraq, which began in 1990 and ended in 1991, approximately 700,000 American soldiers served in the coalition forces. Upon their return, more than 100,000 US veterans reported a vast array of health problems, including irritability, chronic fatigue, shortness of breath, muscle and joint pain, migraine headaches, digestive disturbances, rash, hair loss, forgetfulness, and difficulty concentrating. Collectively, these symptoms were called the Gulf War syndrome. The US Department of Defense acknowledges that up to 20,000 troops serving in the combat area may have been exposed to chemical weapons, and the best evidence indicates that the condition is a disorder that in some cases may have been precipitated by exposure to an unidentified toxin (Table 11.1-5). One study of loss of memory found structural change in the right parietal lobe and damage to the basal ganglia with associated neurotransmitter dysfunction. A significant number of veterans have developed amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), thought to be the result of genetic mutations.

Table 11.1-5

Table 11.1-5

Syndromes Associated with Toxic Exposurea

In a 1997 editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the relationship of the Persian Gulf War syndrome and stress was stated as follows:

Physicians need to acknowledge that many Gulf War veterans are experiencing stress-related disorders and the physical consequences of stress. These conditions should not be hidden or denied, but rather are well-recognized entities that have been studied extensively in survivors of past wars, most notably the Vietnam conflict. As physicians, we should not accept a diagnosis of stress-related disorder in veterans prior to excluding treatable physical factors, but at the same time, we need to recognize the pervasive presence of stress-related illness such as hypertension, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue among Persian Gulf War veterans and manage these illnesses appropriately. As a nation, we need to get beyond the fallacious idea that diseases of the mind either are not real or are shameful and to better recognize that the mind and the body are inextricably linked.

In addition, thousands of Gulf War veterans developed PTSD and the differentiation between the two disorders has proved difficult. PTSD is caused by psychological stress, and Gulf War syndrome is presumed to be caused by environmental biological stressors. Signs and symptoms often overlap and both conditions may exist at the same time.

9/11/01

On September 11, 2001, terrorist activity destroyed the World Trade Center in New York City and damaged the Pentagon in Washington (Fig. 11.1-1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree