2 Traumatic Brain Injury Chad Miller Trauma accounts for over 150,000 deaths in the United States each year. A frequent cause of mortality for this group is head injury, for which over 230,000 patients require hospital care.1 The most common source of traumatic brain injury (TBI) changes with age and includes motor vehicle accidents, physical assault, and falls. The impact of TBI is substantial, considering the disability resulting from injury and the propensity for young individuals to be affected. These facts underscore the importance of prompt and comprehensive treatment for those suffering head injury. Although prevention remains the most effective treatment, recent studies have highlighted the contribution of secondary injury to overall disability in TBI. Standardization of care following evidence-based guidelines has been shown to improve patient outcomes. Level 1 trauma centers are best equipped to deliver this comprehensive care.

History and Examination

History

Physical Examination

Neurologic Examination

| Assessment | Score | |

| Verbal | Alert, oriented, and conversant Confused, disoriented, but conversant Intelligible words, not conversant Unintelligible sounds No verbalization | 5 4 3 2 1 |

| Eye opening | Spontaneous To verbal stimuli To painful stimuli None | 4 3 2 1 |

| Motor | Follows commands Localizes Withdraws from stimulus Flexor posturing Extensor posturing No response to noxious stimulus | 6 5 4 3 2 1 |

Differential Diagnosis

- Traumatic brain injury. May include subdural, epidural, subarachnoid hemorrhage, traumatic parenchymal lesion, diffuse axonal injury, posterior fossa mass lesion, depressed skull fracture. TBI is classified as mild (GCS ≥13), moderate (GCS 9–12) or severe (GCS ≤8).

- Spinal cord injury. May include sensory level, spinal shock (bradycardia, hypotension), initial absence of reflexes

- In falls or when a patient is “found down” with intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), the inciting event could be an aneurysm or AVM rupture, or ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic conversion with secondary trauma. The physician must keep an open mind while caring for patients with unwitnessed events, as the treatment priorities may be quite different from those undertaken for TBI.

Life-Threatening Diagnoses Not to Miss

- Lesions requiring surgical treatment. These include subdural hemorrhage, epidural hemorrhage, depressed skull fracture, posterior fossa lesions, certain parenchymal contusions, elevated intracranial pressure refractory to medical management, and certain spinal cord injuries.

- Elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) (if in doubt, insert an ICP monitor).

Diagnostic Evaluation

- Imaging studies

- Head CT:

- For mild TBI (patients with GCS 15 with loss of consciousness and no neurologic deficit, age >3 years), according to New Orleans Criteria,2 a noncontrast head CT to evaluate for the presence of any abnormality is recommended in patients with headache, vomiting, seizure, intoxication, short-term memory deficit, age >60 years, or injury above the clavicle. According to the Canadian CT Head Rule,3 in patients with GCS 13–15 with loss of consciousness but no neurologic deficit, no seizure, no history of anticoagulation, and age >16 years: patients at high risk for neurosurgical intervention and abnormal head CT include those with GCS <15 at 2 hours postinjury, suspected skull fracture, any sign of basal skull fracture, vomiting (≥2 times), and aged ≥65 years. Medium-risk patients for neurosurgical intervention and abnormal head CT are those with retrograde amnesia >30 minutes, or a dangerous mechanism of injury (pedestrian vs motor vehicle, ejected from motor vehicle, fall from height >1 m or five stairs.)

- All moderate-severe TBI patients require a noncontrast head CT, and, when in doubt, it is appropriate to check a head CT. Head CT can be classified using the Marshall Classification system (Table 2.2).4

- In severe TBI, head CT abnormalities are found in 93% of patients. For severe TBI patients, the absence of abnormalities on head CT is associated with, but does not guarantee, a favorable prognosis. Conversely, obliteration of the basal cisterns confers an unfavorable outcome with a positive predictive value of 97%.5

- Contusions and subdural hemorrhage (SDH) are the most common CT findings in severe TBI, each occurring in about one-fourth of patients, typically at locations where the brain collides with the adjacent skull (orbital frontal, temporal regions). Fluid-fluid levels may indicate coagulopathy.

- SDH results from tearing of bridging veins and has a propensity to expand over time. These concave lesions do not cross the falx but cross suture lines. Mixed density lesions may be seen, indicating aging blood products.

- Traumatic SAH is common and may lead to angiographic vasospasm if extensive (>1 mm in thickness) in 20 to 40% of cases.6 For these reasons, daily assessment of vascular narrowing with transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound is performed at many institutions.

- Epidural hematomas (EDH) occur infrequently (1 to 2%)7and result from temporal or parietal skull fractures, which damage underlying arteries. These lesions are concave and do not cross suture lines. Despite the classical teachings, these bleeds seldom result in a period of lucidity following loss of consciousness.

- Progressive hemorrhagic injury occurs in over 40% of patients with TBI (DTICH—delayed traumatic intracerebral hematoma).8 Neurologic deterioration accompanies many of these changes; however, this progression can be latent, particularly in severe TBI patients with a compromised baseline exam. As a result, severe TBI patients should receive routine head CT scans at 4 to 6 hour intervals until stability of the lesion is confirmed.

- Traumatic arterial dissection can lead to perfusion failure or embolic stroke and can be evaluated by CT angiogram, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the brain and neck or by digital subtraction angiography if there is sufficient suspicion.

- All moderate-severe TBI patients require a noncontrast head CT, and, when in doubt, it is appropriate to check a head CT. Head CT can be classified using the Marshall Classification system (Table 2.2).4

- For mild TBI (patients with GCS 15 with loss of consciousness and no neurologic deficit, age >3 years), according to New Orleans Criteria,2 a noncontrast head CT to evaluate for the presence of any abnormality is recommended in patients with headache, vomiting, seizure, intoxication, short-term memory deficit, age >60 years, or injury above the clavicle. According to the Canadian CT Head Rule,3 in patients with GCS 13–15 with loss of consciousness but no neurologic deficit, no seizure, no history of anticoagulation, and age >16 years: patients at high risk for neurosurgical intervention and abnormal head CT include those with GCS <15 at 2 hours postinjury, suspected skull fracture, any sign of basal skull fracture, vomiting (≥2 times), and aged ≥65 years. Medium-risk patients for neurosurgical intervention and abnormal head CT are those with retrograde amnesia >30 minutes, or a dangerous mechanism of injury (pedestrian vs motor vehicle, ejected from motor vehicle, fall from height >1 m or five stairs.)

- MRI:

- Shearing axonal injury of the brain (diffuse axonal injury) results from torsional traumatic forces and often accounts for disability disproportionate to the CT radiological injury. Gradient echo (GRE) MRI and susceptibility weighted imaging changes, particularly in the corpus callosum and brainstem, represent hemorrhage and diffuse axonal injury (DAI).

- Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences may demonstrate cerebral edema; diffusion-weighted image (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient imaging (ADC) abnormalities may show infarction.

- Shearing axonal injury of the brain (diffuse axonal injury) results from torsional traumatic forces and often accounts for disability disproportionate to the CT radiological injury. Gradient echo (GRE) MRI and susceptibility weighted imaging changes, particularly in the corpus callosum and brainstem, represent hemorrhage and diffuse axonal injury (DAI).

- ICP monitoring

- According to 2007 Brain Trauma Foundation guidelines,9 ICP monitoring should occur in all patients with GCS <9 and an abnormal head CT (e.g. hematomas, contusions, swelling, herniation, or compressed basal cisterns). ICP monitoring is indicated in patients with GCS <9 and a normal CT if two or more of the following are met at admission: age >40, unilateral or bilateral posturing, SBP <90 mm Hg.

- If the patient is comatose and has an abnormal CT, 50 to 60% will have abnormal ICP. If the patient is comatose with a normal CT, 10 to 15% will have abnormal ICP. If two of the following factors are present (age >40, unilateral or bilateral posturing, SBP <90 mm Hg), 33% will have an abnormal ICP.10

- According to 2007 Brain Trauma Foundation guidelines,9 ICP monitoring should occur in all patients with GCS <9 and an abnormal head CT (e.g. hematomas, contusions, swelling, herniation, or compressed basal cisterns). ICP monitoring is indicated in patients with GCS <9 and a normal CT if two or more of the following are met at admission: age >40, unilateral or bilateral posturing, SBP <90 mm Hg.

- Additional testing

- Focused abdominal sonogram for trauma (FAST) exam evaluates pericardium, right and left upper abdomen, and pelvic region for blood.

- CT of chest, abdomen, and pelvis

- In patients with long bone fracture, evaluate creatine kinase (CK), and check compartment pressures for compartment syndrome if CK is elevated.

- Focused abdominal sonogram for trauma (FAST) exam evaluates pericardium, right and left upper abdomen, and pelvic region for blood.

- Head CT:

| Category | Definition |

| Diffuse injury I | No visible pathology on CT |

| Diffuse injury II | Cisterns present with MLS <5 mm; no high-density lesion >2.5 cm |

| Diffuse injury III | Cisterns compressed or absent; no high-density lesion >2.5 cm |

| Diffuse injury IV | MLS >5 mm; no high-density lesion >2.5 cm |

| Evacuated mass | Any lesion surgically evacuated |

| Nonevacuated mass | High-density lesion >2.5 cm; not surgically evacuated |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; MLS, midline shift.

Data from: Marshall LF, Marshall SB, Klauber MR, et al. The diagnosis of head injury requires a classification based on computed axial tomography. J Neurotrauma 1992;9(Suppl 1):S287-S292.

Treatment

Medical Treatment

- Maintenance of ABCs are of paramount importance and supersede all other neurologic concerns. Patients with poor airway protection, GCS <9, or hypoxemia refractory to supplemental oxygen should generally be intubated. Intubation should occur with removal of the C-spine collar and manual stabilization of the C-spine. If intubation is not emergent, options include use of video laryngoscopes or fiberoptic intubation. Unless increased ICP and/or herniation are suspected, normal ventilation (PaCO2 35 to 40 mm Hg) should be targeted.

- Hypoxia and hypotension affect over one-third of all trauma patients and have a disastrous impact on outcome. A single episode of hypotension (SBP < 90 mm Hg) doubles mortality.9 In a randomized trial of TBI patients, initial resuscitation with 7.5% hypertonic saline compared with lactated Ringer revealed no difference in neurologic outcome at 6 months.11 However, hypotonic and dextrose-containing solutions should be avoided to minimize cerebral swelling and hyperglycemia. In a post hoc analysis of TBI patients enrolled in the Saline versus Albumin Fluid Evaluation (SAFE) study, fluid resuscitation with albumin was associated with higher mortality than saline resuscitation.12 Hypoxemia (PaO2 <60 mm Hg) is also associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

- Elevations in ICP occur in many patients with severe TBI. These elevations correlate with poor outcome and must be identified and appropriately treated. See Chapter 15.

- Dysautonomia or sympathetic storming is characterized by episodic hypertension, tachypnea, fever, diaphoresis, dystonia, and posturing. Dysautonomia can persist for months or years and may be due to loss of GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) inhibition of cortical projections. These episodes can be managed with β blockers (centrally acting propranolol), clonidine, opiates, benzodiazepines (midazolam, clonazepam, etc.), gabapentin, pregabalin, bromocriptine, dantrolene, levodopa, chlorpromazine, or baclofen.

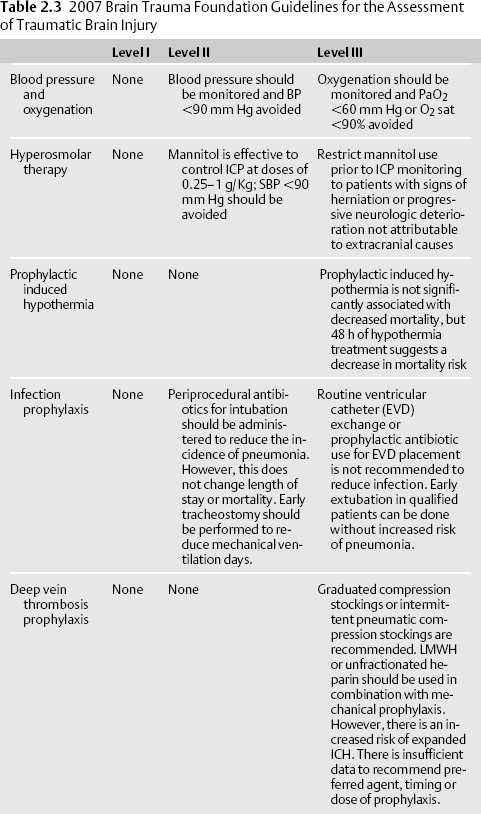

- See the 2007 Brain Trauma Foundation Guidelines in Table 2.39,13,14 for specific treatment guidelines.

- Hypoxia and hypotension affect over one-third of all trauma patients and have a disastrous impact on outcome. A single episode of hypotension (SBP < 90 mm Hg) doubles mortality.9 In a randomized trial of TBI patients, initial resuscitation with 7.5% hypertonic saline compared with lactated Ringer revealed no difference in neurologic outcome at 6 months.11 However, hypotonic and dextrose-containing solutions should be avoided to minimize cerebral swelling and hyperglycemia. In a post hoc analysis of TBI patients enrolled in the Saline versus Albumin Fluid Evaluation (SAFE) study, fluid resuscitation with albumin was associated with higher mortality than saline resuscitation.12 Hypoxemia (PaO2 <60 mm Hg) is also associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree