Treating Patients with Psychological Nonepileptic Seizures

W. Curt LaFrance Jr.

Andres M. Kanner

John J. Barry

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (NES), which are commonly occurring paroxysmal neuropsychiatric disorders, are still situated in the gap between neurology and psychiatry, and treatment remains poorly studied. Also known as pseudoseizures, hysterical seizures, and many other names in the past (1), diagnostic references for NES have been present since the first millennium BC (2), and treatment references have been in the medical literature for more than two-and-a-half centuries (3).

An explosion of NES knowledge occurred beginning in the 1980s largely because of the growth and use of intensive video electroencephalography (VEEG) (4,5,6) Cragar et al. reviewed the diagnostic tests used for NES, including electroencephalography (EEG), neuroimaging, prolactin levels, and personality testing, providing the sensitivities and specificities for each of these tests (8). Diagnosis of NES and these tests are covered in Chapter 25. The gold standard for NES diagnosis remains VEEG. Despite diagnostic advances there is no standardized, effective treatment for NES. Even as our knowledge of NES phenomenology continues to grow, no randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) for NES treatments have been completed.

In contrast to the rapid advances in therapy for other paroxysmal disorders, such as epilepsy, stroke, and bipolar and anxiety disorders, advances have been slower in NES treatment. The lack of “ownership” for NES is a major factor accounting for the lack of therapeutic studies and advances. Although stroke, seizure, and migraine have a home in neurology, and mood and anxiety disorders have a home in mental health practice, no discipline has “claimed” NES. This disorder is best diagnosed by neurologists with expertise in clinical neurophysiology using long-term monitoring and VEEG, and then best treated by psychiatrists or psychologists whose experience affords them a familiarity with psychological constructs and conflicts. This borderland diagnosis leaves many patients improperly diagnosed or inappropriately treated. Even when correctly diagnosed, often the only “treatment” offered to patients is the recommendation to see a mental health care provider, then they are often lost to follow-up (9). On referral for

treatment, many psychiatrists and psychologists may doubt the diagnosis and communicate mixed messages to the patients (10,11). These mixed messages, in combination with a patient’s perception and understanding of his or her NES after diagnosis, greatly affects outcome and functioning (12).

treatment, many psychiatrists and psychologists may doubt the diagnosis and communicate mixed messages to the patients (10,11). These mixed messages, in combination with a patient’s perception and understanding of his or her NES after diagnosis, greatly affects outcome and functioning (12).

Other neurological disorders, such as stroke, can serve as an analogy to better understand NES. Because both are paroxysmal disorders, comparing types of stroke and treatments aids in proposing a neuropsychiatric model for NES semiology and treatment. The treatment of paroxysmal disorders in both neurology and psychiatry utilizes symptomatic and prophylactic therapy. For stroke, we use thrombolytics to treat the acute event—a “clot buster” can have immediate effects on the pathophysiology of ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Another means of treating stroke is through prevention. By treating the risks and precursors to stroke (atrial fibrillation, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smoking), we decrease the incidence of stroke.

For psychogenic NES, no established “NES-olytic” exists. Although we have symptomatic treatment for stroke, we have none for NES. Although hypotheses of psychobiology and functional neuroanatomy of NES have been suggested (13), our current understanding of the underlying cause of NES is based on psychogenic mechanisms (14). For psychiatric disorders, we have two main treatments for “prophylaxis”— psychotherapies and somatic therapies. Just as aggressive management of hypertension and diabetes decreases stroke, case reports suggest that appropriately addressing the psychological issues and the psychiatric comorbid diagnoses may reduce NESs (15,16). Psychotherapy addresses the underlying psychological issues. Therapy and psychopharmacology aid in treating the comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. This prophylactic approach to the paroxysmal neuropsychiatric NES is the basis of the current research on NES reduction and improvement of patient health being conducted at the neuropsychiatry of epilepsy program at Rhode Island Hospital. Distinguishing the psychogenic components and behaviors of NES will also improve epilepsy care in those who have mixed NES and epileptic seizures (ES).

The First Step in Treatment: Diagnosis of Nonepileptic Seizures

Essential to addressing these issues is first obtaining an accurate diagnosis of NES, which is critical for instituting proper therapy and avoiding unnecessary and potentially dangerous therapies. Clinical features of ES and NES overlap, however, and there is no one clinical feature that reliably distinguishes ES from NES, as discussed in Chapter 25. NES are not associated with epileptiform discharges on VEEG recordings, the gold standard for NES diagnosis. Humility in diagnosing NES without VEEG—and sometimes with VEEG—is critical. In one study, prediction of the nature of seizures by the admitting neurologist was accurate in only 67% of cases. Without accompanying EEG, diagnosis based on observations of unit personnel and neurologists was correct in less than 80% of episodes (17).

The co-occurrence of ES and NES in a patient further complicates diagnosis and therapy. The diagnosis comes through careful history, thorough review of medical records, and review by family members of events captured on VEEG that can identify different episode types and assess the supportive data. Abnormalities on EEG in patients with NES do not necessarily rule in the diagnosis of ES. For example, EEG recordings showing “sharpish waves” or paroxysmal slowing provide little support of ES. Furthermore, ES of mesial or orbitofrontal origin often mimic NES, although their scalp VEEG recordings frequently fail to reveal an ictal pattern (18,19,20).

No single psychopathogenic process causes NES. NES are classified under different Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnoses including conversion, somatization, and dissociation disorders and a much smaller percentage as factitious disorder and

malingering. Once the diagnosis of NES is confirmed, a structured psychiatric interview (e.g., Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV [SCID]) and psychosocial history provide critical diagnostic data. A psychosocial stressor (e.g., sexual or physical abuse, loss of a relationship, work stress, parental divorce) (21) is often identified but may take months to uncover. Many patients with NES also have mood (12% to 100%), anxiety (11% to 80%), personality (33% to 66%), nonseizure conversion/somatoform (20% to 100%), and nonseizure dissociative disorders (up to 90%) co-occurring with their primary NES diagnosis of conversion, somatoform, or dissociative disorder (22).

malingering. Once the diagnosis of NES is confirmed, a structured psychiatric interview (e.g., Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV [SCID]) and psychosocial history provide critical diagnostic data. A psychosocial stressor (e.g., sexual or physical abuse, loss of a relationship, work stress, parental divorce) (21) is often identified but may take months to uncover. Many patients with NES also have mood (12% to 100%), anxiety (11% to 80%), personality (33% to 66%), nonseizure conversion/somatoform (20% to 100%), and nonseizure dissociative disorders (up to 90%) co-occurring with their primary NES diagnosis of conversion, somatoform, or dissociative disorder (22).

The Nonepileptic Seizures Treatment Literature

Introduction

Neurological, psychiatric, and psychological publications are replete with descriptions of NES. Hundreds of articles describe ictal semiology, psychiatric comorbidities, neurological findings, psychological makeup, and neuropsychological testing in patients with NES. Controlled treatment trials for NES, however, are lacking. The NES treatment literature was reviewed, and most of the articles consisted of class IV reports (case reports or case series), with a handful of class III reports (23). There are no published double-blind RCTs for treatment of NES. As the NES treatment research literature matures, we are beginning to see an increase in prospective trials. There are, however, only a few open-label trials of medications and psychotherapies to treat NES.

In our review of the NES treatment literature using 11 keywords for NES (e.g., NES, pseudoseizure, psychogenic seizure, conversion epilepsy), we identified more than 500 articles on NES; 200 of which were journal articles, 95 were review articles or chapters (23). Eighty mention treatments for NES. There are five books specifically focused on NES (24,25,26,27,28). The literature provides widely divergent views on natural history and outcome, as well as the value of psychotherapy, psychotropic medication, and other interventions for NES (29,30,31,32). More than two centuries after this disorder was clearly identified in medical literature, we still need controlled treatment trials for this costly and disabling disorder.

Historical Treatment Approaches to Nonepileptic Seizures

In the late nineteenth century, the neuropsychiatric syndrome of NES was established in the German, French, and British medical literature (referred to as hysteroepilepsy). Briquet, Charcot, Richer, and Gowers described NES, but the French and English differed in the treatment approaches (33,34,35,36). Charcot, with his understanding of hypnosis, likely utilized the power of suggestion, and he promoted ovarian compression for treatment of acute attacks. Gowers endorsed aversive therapies such as closing the nose and mouth, faradization (electric shock to the skin), and hydrotherapy. Long-term management for both consisted of environmental changes with removal from the home, suggesting that family dysfunction can influence NES recurrence. Charcot’s ovarian compression methods were not as readily accepted in the United States as they were in Europe, as noted in a letter by Dr. Wood to the American Journal of Insanity (37).

Modern Treatment Approaches to Nonepileptic Seizures

Although our treatments are refined in the sense that we psychopharmacologically target neurotransmitter abnormalities in patients or treat them with individualized psychotherapies, after more than 200 years, we have added only a few prospective trials to empirically test the outcome from our treatments for NES. Despite this, we can learn about NES treatment from the numerous case reports, case series, retrospective treatment reports, and a handful of prospective studies.

The NES psychotherapy data include case reports, small uncontrolled trials, or

medium-size retrospective follow-up studies. We reviewed all of the NES treatment literature and included the articles that gave clear descriptions of their treatment(s) and the individual/population treated, in Table 27.1 (where repeated treatment descriptions in case reports were found, we included only the earliest noted article). The vast majority of the treatment trials for NES to date would be considered class IV data and a few would be considered class III studies that utilized a control or comparison group (Table 27.1). Outcomes in these reports are discussed as follows.

medium-size retrospective follow-up studies. We reviewed all of the NES treatment literature and included the articles that gave clear descriptions of their treatment(s) and the individual/population treated, in Table 27.1 (where repeated treatment descriptions in case reports were found, we included only the earliest noted article). The vast majority of the treatment trials for NES to date would be considered class IV data and a few would be considered class III studies that utilized a control or comparison group (Table 27.1). Outcomes in these reports are discussed as follows.

A chart review of patients with NES (38) found that matching specific psychotherapies to the patient’s comorbid diagnoses produced greater seizure-free rates, with 21

of 33 patients (63%) reaching event-free status at the end of treatment. The pharmacological references for NES treatment using intravenous barbiturates, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), β-blockers, analgesics, or benzodiazepines are anecdotal references in case reports, journal review articles, or book chapters (16,39,40,41,42).

of 33 patients (63%) reaching event-free status at the end of treatment. The pharmacological references for NES treatment using intravenous barbiturates, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), β-blockers, analgesics, or benzodiazepines are anecdotal references in case reports, journal review articles, or book chapters (16,39,40,41,42).

TABLE 27.1 Classification of Nonepileptic Seizure Treatment Reports | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reported outcomes in NES treatment vary from greatly successful to not impressive. The higher success rates are noted in the treatment articles and chapters describing longer inpatient admissions where patients were managed by a multidisciplinary team familiar with NES (52). More recent reviews, however, reveal that roughly one third of the patients have NES cessation, and another third have reduction in their NES (80). However, quality of life measures improve when patients reach NES freedom, and not when their NES are merely reduced (81). Reuber et al. discussed appropriate outcome measures in NES noting the importance of other psychosocial measures, along with NES frequency (82).

Even with NES improvement, up to half of the patients remain on government or family support and are unemployed (83), and patients with NES generally do not expect to return to work (84). One study found that patients with NES scored higher on hypochondriasis and somatic-complaint scales of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory when compared with patients with epilepsy (PWE), reflective of a focus on bodily function and neurological

complaints (85). Poor quality of life in patients with NES may partly result from their somatic focus. A factor analysis of predictors of health-related quality of life revealed that patients with NES had more bodily concern than those with epilepsy (86), and that somatic focus may influence health-related quality of life.

complaints (85). Poor quality of life in patients with NES may partly result from their somatic focus. A factor analysis of predictors of health-related quality of life revealed that patients with NES had more bodily concern than those with epilepsy (86), and that somatic focus may influence health-related quality of life.

Treatment Theories

Interventions chosen for NES treatment may be based on the etiological conceptualization for NES. Some of the proposed etiologies include neuroanatomical/pathophysiological, psychodynamic with trauma and dissociation, psychosomatic misinterpretation, interpersonal, cognitive-behavioral, intellectual/learning difficulties, volitional feigning with conscious or unconscious awareness, communication difficulties, and family system disturbances (13,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95). Although trauma is frequently found in patients with NES, it is not universal. Bjørnæs’ reviewed etiological models for NES (87).

Biomedical approaches highlight the absence of epileptiform activity during NES, demonstrating a functional-neuroanatomic dissociation model for NES (42,89). Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) do not treat NES and in some patients can worsen NES (96). Antidepressant, antianxiety, and antipsychotic therapies (e.g., medication and psychotherapy) can treat symptomatic comorbid disorders and may also indirectly improve NES frequency or severity. Psychodynamic approaches view NES as being triggered by unresolved, strong, painful emotions caused by trauma, abuse, or loss. The events function as primary gain by being a psychological defense against the emotion, allowing painful emotions to remain in the unconscious, whereas on the surface the patient appears nondistressed (97). Behaviorists conceptualize NES as an arousal disorder, with NES triggered by stimuli that intensify autonomic arousal (74). These stimuli could be environmental or stimulant agents, or emotional traumatic memories. Family theorists highlight dysfunctional communication and roles in patients with NES and theorize that strong secondary gain (benefits from illness) results from long-standing NES, and that families are emotionally enmeshed with each other (83). Treatments based on these theoretical models are largely anecdotal case reports or series demonstrating only modest outcomes, at best.

The literature for NES reveals a wide range of percentages for outcomes across a variety of psychotherapies, noted in the previous text. Patients with NES generally have poor-to-fair treatment outcomes, but children and adolescents tend to do better than adults. In one study, outcome was significantly better for the younger patients at 1, 2, and 3 years after diagnosis (seizure-free percentages were children 73%, 75%, 81%; adults 25%, 25%, 40%, respectively). The authors proposed that different psychological mechanisms at different ages of onset and greater effectiveness with earlier intervention may be factors leading to better outcome in children and adolescents (98).

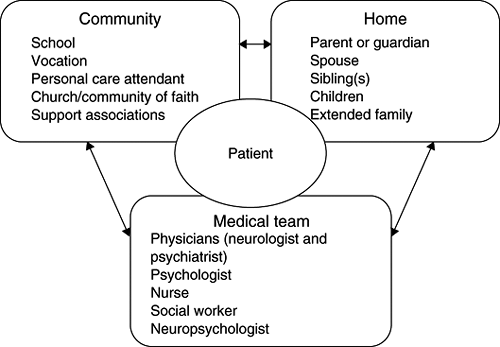

NES are currently treated as a psychiatric illness with psychological underpinnings. Both psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological interventions are used. These approaches fall under the headings of psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), family systems therapies, behavioral modification (mainly for mentally retarded individuals), and biological psychiatric treatments. Because of the variety of neurological, psychiatrical, and psychosocial issues present in the lives of patients with NES, a multisystem treatment approach has been proposed (Fig. 27.1) (23). The fact that different modalities are being used in NES treatment illustrates that NES may have different underlying causes.

In the following section, we will describe the main conceptualizations of NES, as well as treatment approaches for patients with NES. The treatment models include pharmacotherapy, CBT, psychodynamic psychotherapy, hypnosis, group therapy, and family therapy. We will address these interventions and their application to NES treatment, treatment in the inpatient and outpatient settings, and the most recent studies examining these models. We will

conclude with directions for future research in NES treatment trials.

conclude with directions for future research in NES treatment trials.

Figure 27.1 Systems model for prevention and treatment of nonepileptic seizures (23). From LaFrance WC Jr, Devinsky O. The treatment of nonepileptic seizures: historical perspectives and future directions. Epilepsia 2004;45(Suppl 2):15–21 |

Treatment of Nonepileptic Seizures

Patients who display nonepileptic events do so as a result of an array of potential etiologies. Many of these have been outlined and categorized by other authors (99). The diagnosis of NES is often seen as a unitary disorder or syndrome. Just as the behavioral manifestations of NES vary tremendously, the underlying etiologies are also varied. There are many etiologies for right hemiparesis with aphasia in a patient with stroke (e.g., atrial fibrillation–induced cardioembolic ischemic stroke, amyloid angiopathy, tumor with hemorrhagic necrosis). Similarly, there are potentially many etiologies for NES. Precursors to psychogenic NES include childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, comorbid psychiatric conditions, minor head trauma, disability claims, and reinforced behavioral patterns, amongst others. By identifying signs, symptoms, and situations that are associated with NES in a patient, we can provide interventions to promote the mental, physical, and social health of the patient (95).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree