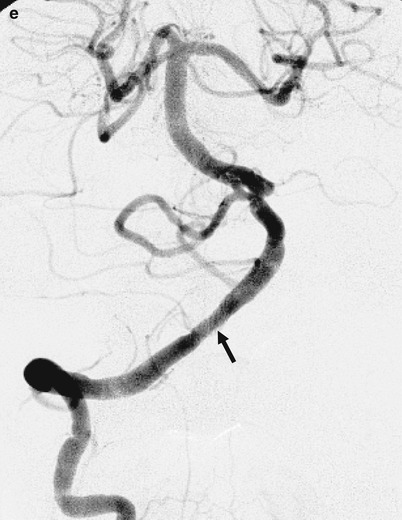

Fig. 1

(a) Anteroposterior view of a right vertebral artery angiogram demonstrating high-grade stenosis (arrow) of a right vertebral artery. (b) Lateral view of a left vertebral artery angiogram before treatment, demonstrating occlusion of a left vertebral artery. (c) Lateral view of a right internal carotid artery angiogram. Right posterior communicating artery was not revealed. (d) Lateral view of a left common carotid artery angiogram. Left posterior communicating artery was not revealed. (e) Anteroposterior view of a right vertebral artery angiogram demonstrating sufficient dilatation of the lesion (arrow)

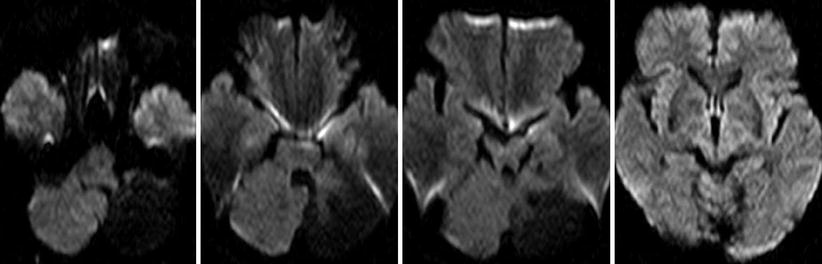

Fig. 2

MRI DWI imaging after stenting showing no fresh infarction

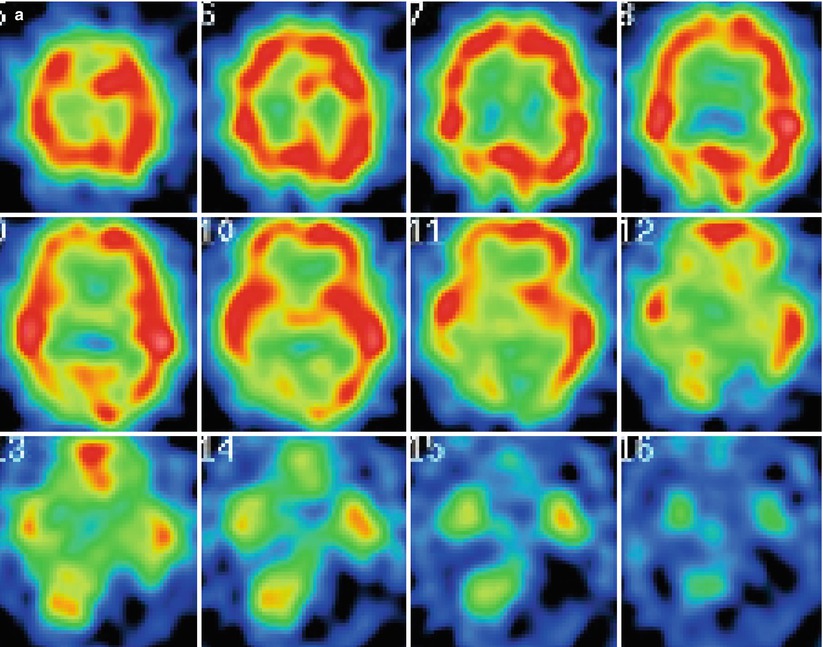

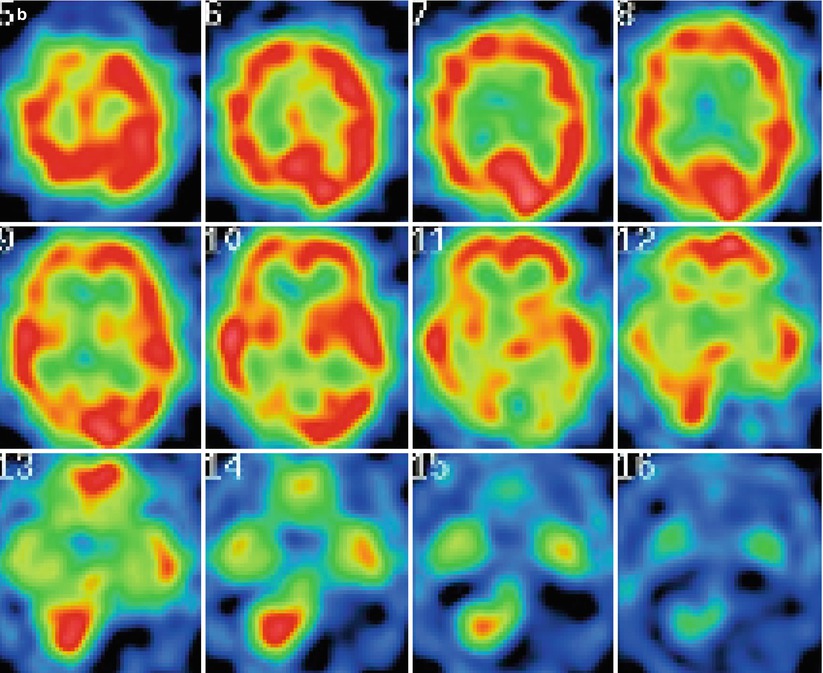

Fig. 3

(a) SPECT before treatment demonstrating a decline of cerebral blood flow in the cerebellum, brain stem, and bilateral occipital lobes. (b) SPECT after treatment demonstrating an increase of cerebral blood flow in the right cerebellum, brain stem and bilateral occipital lobes

Discussion

Transient ischemic attacks of the posterior circulation are associated with a 22–35 % risk of stroke in 5 years, and infarction of the vertebrobasilar artery carries a serious prognosis [1, 5, 13]. WASID investigators suggest that 35–40 % of intracranial atherosclerosis cases involve the vertebrobasilar vessels [12]. Medical treatment, such as anticoagulation and antiplatelet aggregation therapy, does not consistently benefit patients. The annual vertebrobasilar territory stroke rate in nonsurgically treated patients with vertebrobasilar stenosis of at least 50 % was 8.7 % in the WASID study. In particular, symptomatic patients with hemodynamic compromise, such as the case presented here, cannot be expected to ameliorate the symptoms and prevent recurrent stroke with medical treatment. The limitations of standard medical treatment have encouraged the development of endovascular surgery for IAS. Currently there are three main endovascular procedures available for IAS: balloon angioplasty, angioplasty with a balloon-expandable stent, and balloon angioplasty with a self-expandable stent. Balloon angioplasty for vertebrobasilar artery stenosis was introduced in the early 1980s as an alternative to surgery by Sundt et al. [10]. The advantages of this procedure are straightforwardness and the ability to follow up noninvasively with MRA after treatment. However, its usefulness has been limited by immediate complications including elastic recoil, wall dissection, and vessel rupture [2, 6, 8, 11]. These limitations have fueled interest in treating these lesions using stents. Theoretically, stenting improves the acute and long-term patency and reduces the risk of acute closure from dissection by trapping plaque material between the stent and arterial wall. The advent of the self-expanding stent has enhanced the accessibility of the intracranial lesions and has increasingly been used for IAS [4, 7].

Recently, the results of the SAMMPRIS trial demonstrated a higher-than-expected 30-day stroke rate in the stent plus medical therapy arm (14.7 %), and a lower-than-expected 30-day stroke rate in the medical therapy alone arm (5.8 %). The difference in the 30-day stroke rate between the two arms was statistically significant [9]. In our series, technical success was achieved in all patients, and the rate of stroke and death within 30 days was 2.3 %. Our results of endovascular treatment were better than those of reported series [2, 4, 6–9, 11]. We can speculate on some of the reasons for our favorable result: (1) Under dilatation: The mean stenosis rate after endovascular treatment was greater than 15 % in the current study. Intracranial arteries are delicate and thin-walled vessels, with a greater risk of rupture, which can result in lethal bleeding [4, 7–10]. Therefore, we under-dilate these arteries with or without stents. The relative under-dilatation can prevent lethal complications, such as subarachnoid hemorrhage. Indeed, there was no bleeding complication in our series. (2) Patient selection: The lesions we treated were accessible with coronary stents and short (>15 mm) lesions. The risk of periprocedural ischemic complications may be low in these patients, because of a small plaque volume, fewer perforators within the lesion, and fewer obstacles in the approach route to the lesion. (3) IAS of the vertebro-basilar arteries may be more suitable for endovascular treatment than that of the anterior circulation. In the SAMMPRIS trial, a considerable number of IAS cases involving anterior circulation were enrolled. The high complication rate of endovascular treatment influenced the poor outcome of the trial.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree