3 Treatment of bipolar depression

3.1 What is the best medication for depression in someone who has a history of mania (bipolar I depression)?

![]() Giving antidepressants on their own to a patient with a history of mania is not to be recommended because antidepressants can precipitate mania (see Q 3.15).

Giving antidepressants on their own to a patient with a history of mania is not to be recommended because antidepressants can precipitate mania (see Q 3.15).

Another reason to avoid monotherapy with antidepressants is that the commonest time to become manic is following an episode of depression and consideration should be given to how to prevent this happening. Although antidepressants are the mainstay of treatment for bipolar depression they should only be used in combination with a medication that will prevent mania (see Q 3.6).

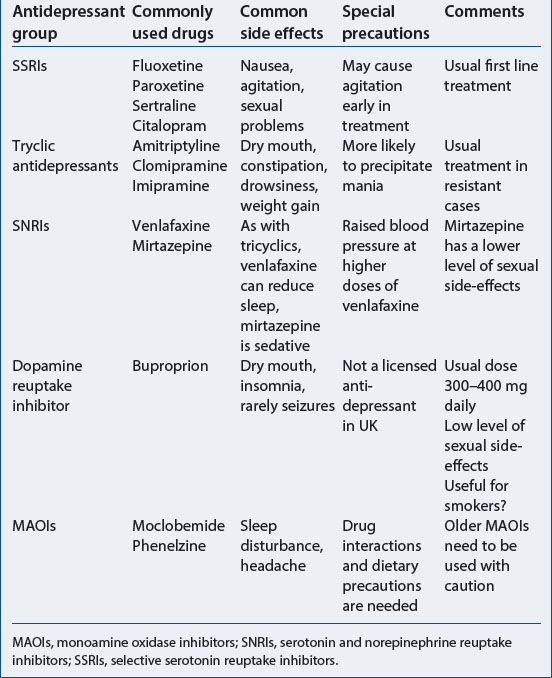

3.3 Which types of antidepressant are commonly available?

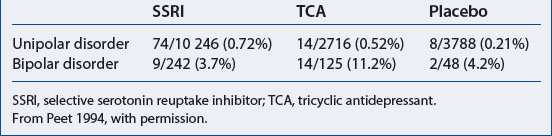

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly used antidepressants in the UK. They are not only the first line treatment for unipolar depression but also the first line treatment for bipolar depression. Tricyclic antidepressants are also effective in the treatment of both unipolar and bipolar depression (Table 3.1).

The benefits of SSRIs over tryclics are that they are simple to take (usually once daily dosage) and the initial dose is usually an effective dose. In addition, SSRIs are less likely to cause manic switch than tricyclics (Table 3.2). In contrast the tricyclics require a gradual increase to an effective dose because of side-effects, usually over at least 2 weeks. The level of side-effects of SSRIs is low and they are relatively safe if taken in overdose.

There have been reports that agitation and suicidal impulses may be increased in the first few weeks on SSRIs (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency 2003). It is difficult to disentangle this effect from a deteriorating depression which is not responding to treatment, as suicidal thoughts are an integral part of depression (see Q 1.8).

3.4 Are there any other types of antidepressant used in the treatment of bipolar depression?

MOCLOBEMIDE

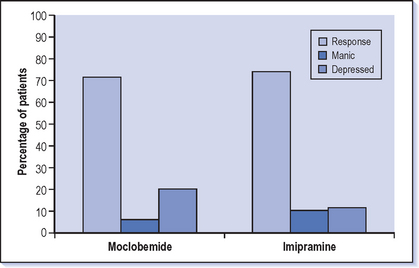

Moclobemide (Manerix) has been shown to be effective and to have a low propensity for ‘switch’ into mania compared to the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine (Silverstone 2001) (Fig. 3.1). Moclobemide is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) which often worries prescribers because of concerns about dangerous interactions with foods (the cheese reaction occurs when the amino acid tyramine passes through the gut without being broken down and leads to a rise in blood pressure). However, moclobemide is a specific inhibitor of monoamine oxidase in the brain and does not inhibit the form found in the gut. Tyramine can therefore still be broken down in the gut and so does not get through to cause a hypertensive reaction. Moclobemide is also a reversible inhibitor and is relatively short lived so there is only a short (days) wash-out period before another antidepressant can be started if there is a need to change treatment.

3.5 For how long should antidepressants be continued after recovery from depression?

The concern for bipolars who continue antidepressants is that they may be running an increased risk of mania while they are on this treatment. Because of this it would be recommended to discontinue antidepressants at an early stage after recovery from bipolar depression at about 3 months. This is in contrast to the advice for those with unipolar depression which is to continue the antidepressants for at least 6 months after recovery. Unipolar depressives are also often advised to take antidepressants long term as preventive treatment; however this would not usually be appropriate for bipolars.

For bipolars consideration needs to be given to effective long-term preventive treatment such as lithium (see Chapter 4). If they are to continue with antidepressants they must also take an antimanic drug, such as lithium, an antipsychotic or valproate (see Q 3.7).

3.6 Should bipolars continue on their long-term preventive treatment if they become depressed?

![]() Definitely. It is very important that long-term prophylactic treatment (e.g. with lithium) is continued when the patient becomes depressed. This is because the depression is most likely being treated with antidepressants and if the lithium is stopped there is an increased chance of switching into mania (Fig. 3.2). Obviously at some point the patient will need to be reviewed to assess how effective the preventive treatment is, but the usual time to do this is after recovery from the acute episode of depression.

Definitely. It is very important that long-term prophylactic treatment (e.g. with lithium) is continued when the patient becomes depressed. This is because the depression is most likely being treated with antidepressants and if the lithium is stopped there is an increased chance of switching into mania (Fig. 3.2). Obviously at some point the patient will need to be reviewed to assess how effective the preventive treatment is, but the usual time to do this is after recovery from the acute episode of depression.

3.7 Is there a role for long-term antidepressants as a way of preventing depression recurring in bipolars?

Many bipolar II patients are treated successfully in the long term with antidepressants without lithium or other preventive treatments. This usually follows on from a period of treatment with antidepressants that has been successful without a switch into hypomania. As long as an eye is kept on making sure that elated periods are not occurring, then this is a reasonable option. However, there is a need to be wary as many of those who suffer from hypomanias are not good at recognising them or tend to play down the problems that they cause. Ask someone else in the family if the patient is getting on reasonably.

3.8 What is the best medication for depression in someone who has a history of hypomania but has never been manic (bipolar II depression)

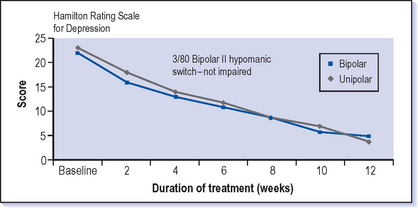

The mainstay of treatment for bipolar II depression is antidepressants, one option being the SSRI fluoxetine (Fig. 3.3). However, the initial decision to be made is whether to prescribe a drug that will prevent manic symptoms developing in addition to the antidepressant. This is a matter of judgement–at one end of the scale a patient who has had only short-lived and not disabling hypomania in the past is suitable for antidepressant treatment on its own but with monitoring for the appearance of manic symptoms. At the other end, someone who is currently depressed but with previous prominent, frequent and socially disabling hypomania should certainly be taking treatment to prevent further manic symptoms along with the antidepressant. Judging where a patient is on this spectrum is difficult and prescribing treatment often requires a lot of negotiation as many patients will be keen to relieve the depression but may not be concerned about hypomanic symptoms. It is usually the case that the manic depressive patient is very keen to relieve and prevent depression but the family (and others including doctors) are more concerned about the social disruption of hypomania.

Fig. 3.3 Treatment of depression with fluoxetine in bipolar and unipolar patients.

(From Amsterdam et al 1998, with permission.)

CASE VIGNETTE 3.1 ANTIDEPRESSANTS MAY DESTABILISE THE COURSE OF BIPOLAR ILLNESS

CASE VIGNETTE 3.1 ANTIDEPRESSANTS MAY DESTABILISE THE COURSE OF BIPOLAR ILLNESS

A bad spell of depression then hit her and she was off work for a month and started treatment with an antidepressant. This seemed to get her right within a couple of weeks but she went a bit more over the top and to her embarrassment ended up sleeping with one of her salesman who was 10 years her junior. This led to another spell of depression but an increase in the antidepressant again led to improvement. However, by the end of the year she was feeling ‘all over the place’, never knowing how her mood was going to be week to week. Her work was going badly as she was now regarded as a liability when previously reliability was her middle name.

3.9 What if the depression is not improving with antidepressant treatment?

The following questions should be considered before contemplating a change in medication:

Have you given the treatment long enough?: At least 4 weeks with no response, or 6 weeks with only minor response. It can be difficult to stick with the treatment when there is little improvement; a realistic time scale for improvement should be discussed with the patient from the beginning–it may well take up to 4 weeks to start to see a difference. It is also worth discussing at this point the balance between the time needed to give this treatment a good try against the time it will take to make a changeover to another medicine. Focusing on other ways that the patient can help to make a difference to the level of depression is also useful (see Qs 3.29 and 3.36).

Have you given the treatment long enough?: At least 4 weeks with no response, or 6 weeks with only minor response. It can be difficult to stick with the treatment when there is little improvement; a realistic time scale for improvement should be discussed with the patient from the beginning–it may well take up to 4 weeks to start to see a difference. It is also worth discussing at this point the balance between the time needed to give this treatment a good try against the time it will take to make a changeover to another medicine. Focusing on other ways that the patient can help to make a difference to the level of depression is also useful (see Qs 3.29 and 3.36). Have you tried a high dose?: If the patient is not improving, doses should be increased to the maximum, provided that the treatment is reasonably tolerated before turning to an alternative antidepressant.

Have you tried a high dose?: If the patient is not improving, doses should be increased to the maximum, provided that the treatment is reasonably tolerated before turning to an alternative antidepressant. Have you assessed concordance/compliance?: Is the patient really in agreement with this treatment and taking it (see also Q 5.43)? Are they forgetting because they are feeling so tired, lethargic and can’t remember to do anything including taking the tablets? Is there some way of improving this–linking it with some more routine or habitual aspect of their life (e.g. brushing their teeth)?

Have you assessed concordance/compliance?: Is the patient really in agreement with this treatment and taking it (see also Q 5.43)? Are they forgetting because they are feeling so tired, lethargic and can’t remember to do anything including taking the tablets? Is there some way of improving this–linking it with some more routine or habitual aspect of their life (e.g. brushing their teeth)? Is there another medication that they are taking that might be affecting their depression (e.g. steroids)?

Is there another medication that they are taking that might be affecting their depression (e.g. steroids)?3.10 What are the next lines of treatment in bipolar depression that has not responded to the first antidepressant treatment?

If this is not successful, continue the lithium but change the antidepressant to a different class of drug. It would be worth reviewing what treatments the patient has been on previously to see if it is possible to identify another drug that has been helpful in the past. If no clear treatment option is apparent the usual rule of thumb is that if the patient has been on an SSRI, change to a tricyclic and vice versa.

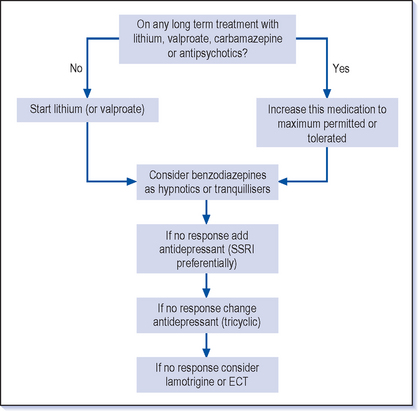

Other options that are available include other groups of antidepressants, thyroid hormone (at above replacement levels), lamotrigine, tryptophan or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (see Q 3.22) (Fig. 3.4) and psychotherapeutic talking treatments (see Qs 3.20 and 5.46).

3.13 Is the treatment for depression in adolescents different?

There are very few trials of treatment of bipolar depression but there are virtually no data on the treatment of bipolar depression in adolescents. There have been concerns that unipolar depression in this age group does not show a good response to antidepressant medication. This is difficult to reconcile with the data for adults which show a clear benefit in improving depression–is there some basic change in depression and its response to treatment at 18 (or 17)? There are also concerns that some antidepressants (SSRIs) can cause agitation and an increase in suicidal thoughts and behaviour, and that this effect is more marked in adolescents.

Overall, even more care needs to be taken when considering the treatment for bipolar depression in adolescents. However, the same lines of treatment as for adults should be followed. Keeping a long-term perspective and focusing on appropriate longer term preventive treatment is a good basic principle, though severe depressive episodes will require antidepressant treatment despite the current uncertainties.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree