4 Treatment of mania

4.1 What is the best treatment for mania?

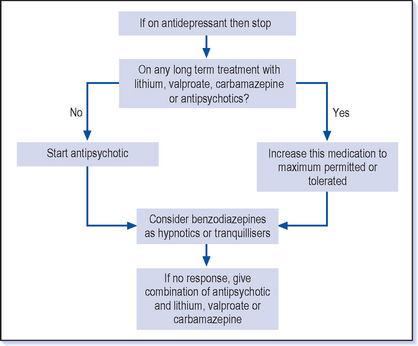

![]() The first step in the treatment of mania is to stop the antidepressants. There are then two main lines of treatment in acute manic relapses. The first is to increase the long-term treatment–for example if the patient is already taking lithium then the levels should be checked and, providing it is being tolerated reasonably well, to increase the dose, aiming for a level of up to 1.0 mmol/l (occasionally up to 1.2 mmol/l). A similar approach can be adopted with valproate and carbamazepine. The alternative line is to give a specific antimanic treatment, usually an antipsychotic, either on its own or in combination with a long-term treatment (Fig. 4.1).

The first step in the treatment of mania is to stop the antidepressants. There are then two main lines of treatment in acute manic relapses. The first is to increase the long-term treatment–for example if the patient is already taking lithium then the levels should be checked and, providing it is being tolerated reasonably well, to increase the dose, aiming for a level of up to 1.0 mmol/l (occasionally up to 1.2 mmol/l). A similar approach can be adopted with valproate and carbamazepine. The alternative line is to give a specific antimanic treatment, usually an antipsychotic, either on its own or in combination with a long-term treatment (Fig. 4.1).

4.2 How are antipsychotics used in mania?

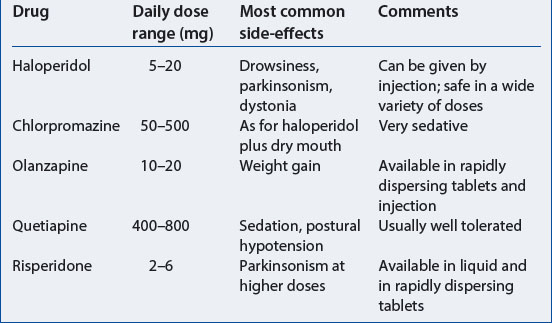

Olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone are the atypical antipsychotics that are licensed for the treatment of mania but it is probably true that all antipsychotic drugs, including the newest one, aripiprazole, improve manic symptoms. These drugs are relatively free of parkinsonian side-effects, and are generally well tolerated (Table 4.1). They are available in either rapidly dispersing tablets or liquid which can be helpful when compliance is in doubt. Olanzapine is now also available as an injection.

4.4 What other treatments are effective in mania apart from antipsychotics?

VALPROATE

Valproate is the main alternative acute treatment and has the advantage of being effective, well tolerated and easy to use. Depakote is the formulation that is licensed for the treatment of mania as the studies have been done using this form (Bowden et al 2000, NICE Technology Appraisal 66). This particular formulation provides higher blood levels for the same apparent dose compared to other forms of valproate. The usual starting dose is 750 mg daily (250 mg tablets spread over two doses). It can then be increased gradually over a week up to 1500 mg or further to 2 g if necessary. It would seem likely that the other forms of valproate are also effective but licensed preparations are generally preferred (see National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidelines, www.nice.org.uk).

LITHIUM

Lithium is also an effective antimanic treatment and is used in similar doses and with similar blood levels to those used in preventive treatment (see Chapter 5). Higher doses with levels up to 1.0 mmol/l or even slightly higher than this are sometimes used. There are several difficulties in using lithium in mania:

Patients who are severely ill may be drinking little and are therefore liable to dehydration; this makes treatment with lithium more difficult and potentially dangerous.

Patients who are severely ill may be drinking little and are therefore liable to dehydration; this makes treatment with lithium more difficult and potentially dangerous. It is difficult to find the effective dose rapidly as increases are usually done gradually: it can take a couple of weeks to reach a therapeutic dose and manic symptoms often need more urgent treatment than this.

It is difficult to find the effective dose rapidly as increases are usually done gradually: it can take a couple of weeks to reach a therapeutic dose and manic symptoms often need more urgent treatment than this. Another reason relates to starting a long-term preventive treatment when a patient is manic and is not capable of making longer term decisions. Stopping lithium suddenly can cause a rebound manic effect (see Chapter 5). If lithium is started when patients are acutely manic and not committed to long-term treatment, they are likely to stop when they have recovered and this will risk precipitating a further episode of mania. This effect is not so apparent with antipsychotics and valproate.

Another reason relates to starting a long-term preventive treatment when a patient is manic and is not capable of making longer term decisions. Stopping lithium suddenly can cause a rebound manic effect (see Chapter 5). If lithium is started when patients are acutely manic and not committed to long-term treatment, they are likely to stop when they have recovered and this will risk precipitating a further episode of mania. This effect is not so apparent with antipsychotics and valproate.BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines are also commonly used in mania. They are used generally for their sedative effect and particularly in cases where urgent calming and sleep induction are necessary. Lorazepam (0.5-1 mg) as an intramuscular injection is an effective emergency treatment for acute psychosis including mania (see Q 4.9). In the early days of treating excited manic patients many doctors give diazepam which has a long half-life, helps to improve sleep and has a calming effect during the day. Clonazepam is also used and there have been some studies to show this is effective in mania on its own, though it is unusual to treat mania only with benzodiazepines.

4.5 What if the mania is not improving on antimanic treatment?

This is a similar answer to that of treating depression that does not improve (see Q 3.9). The following questions should be considered before contemplating a change in medication:

Have you given the treatment long enough?: For example, at least 4 weeks with no or only minor response. It can be difficult to stick with the treatment when there is little improvement, but if the treatment is changed too early the benefits of the medication may be missed.

Have you given the treatment long enough?: For example, at least 4 weeks with no or only minor response. It can be difficult to stick with the treatment when there is little improvement, but if the treatment is changed too early the benefits of the medication may be missed. Have you tried a higher dose?: If the patient is not getting better, doses should be increased to the maximum dose that is recommended, provided that the treatment is reasonably tolerated before turning to an alternative antimanic.

Have you tried a higher dose?: If the patient is not getting better, doses should be increased to the maximum dose that is recommended, provided that the treatment is reasonably tolerated before turning to an alternative antimanic. Have you assessed concordance/compliance?: This is usually a problem in the treatment of mania as most patients have limited insight into their condition and so are unlikely to be taking the treatment correctly. There is also a fair chance that they are deliberately concealing their non-compliance rather than refusing. It is not uncommon to find a stack of tablets hidden away in a patient’s room when they have appeared entirely willing to take the treatment (see also Q 5.43). Can you arrange some supervision of the treatment and give it in a formulation that is harder to evade–a liquid or dispersible tablet?

Have you assessed concordance/compliance?: This is usually a problem in the treatment of mania as most patients have limited insight into their condition and so are unlikely to be taking the treatment correctly. There is also a fair chance that they are deliberately concealing their non-compliance rather than refusing. It is not uncommon to find a stack of tablets hidden away in a patient’s room when they have appeared entirely willing to take the treatment (see also Q 5.43). Can you arrange some supervision of the treatment and give it in a formulation that is harder to evade–a liquid or dispersible tablet? Have you got the diagnosis right?: For example, is this really an episode of mania or is this a drug or alcohol problem?

Have you got the diagnosis right?: For example, is this really an episode of mania or is this a drug or alcohol problem?4.6 What are the next lines of treatment in mania that has not responded to the first antimanic treatment?

There are other options available but these would usually be restricted to specialist use. These include carbamazepine, lamotrigine (see Q 3.4), benzodiazepines (including clonazepam) or ECT (see Q 3.22).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree