• Measure waist circumference.

• Review the patient’s medical condition.

Assess comorbidities:

How many are present, and how severe are they?

Do they need to be treated in addition to the effort at weight loss?

• Look for causes of obesity including the use of medications known to cause weight gain.

• Assess the disease risk of this patient’s obesity using Table 23-3.

• Is the patient ready and motivated to lose weight?

• If the patient is not ready to lose weight, urge weight maintenance and manage the complications.

• If the patient is ready, agree with the patient on reasonable weight and activity goals and write them down.

• Use the information you have gathered to develop a treatment plan based on Table 23-4.

• Involve other professionals, if necessary.

• Don’t forget that a supportive, empathetic approach is necessary throughout treatment.

History

Disorders Associated with Obesity

The patient’s history is important for evaluating associated risks and for developing a treatment plan. Patients should be asked questions regarding age of onset of obesity, minimum weight as an adult, events associated with weight gain, recent weight-loss attempts, previous weight-loss modalities (both successful and unsuccessful), and any complications they may have experienced. For example, achieving a weight below a patient’s minimum weight as an adult is unusual, and an earlier age of onset of obesity often, but not always, predicts a less successful weight loss outcome. A treatment modality that was previously unsuccessful, or during which the patient experienced complications, should generally be avoided. A history of eating disorders, bingeing, and purging by vomiting or laxative abuse are relative contraindications to weight-loss treatment. In these areas referral to a specialist is indicated. Alcohol or substance abuse requires specific treatments that should take precedence over obesity treatment. Cigarette smoking can complicate treatment history because, after stopping, weight is often gained. While smoking cessation is of paramount importance, implementing a diet and exercise program on or before smoking cessation can minimize associated weight gain.

Assessing the patient’s current level of physical activity is important and is helpful in determining a starting point for exercise recommendations. While some individuals may be completely sedentary, others are vigorously active, and the same recommendation to both would be inappropriate. Similarly, the patient’s level of understanding of nutrition will determine whether a basic or more sophisticated level of nutrition education should be used. Material that is too advanced won’t be retained, and material that is too basic will be boring to the patient.

Diseases that may have an effect on weight, such as polycystic ovary syndrome and hypothyroidism, require specific treatment, even though treatment of the condition alone may not result in any weight loss. Patients may also exhibit substantial weight gain in the months or years before developing overt type 2 diabetes.

Complications of Obesity

The clinician should search for complications of obesity, such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, osteoarthritis of the lower extremities, gall bladder disease, gout, and certain cancers. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of colorectal and prostate cancer in men and with an increased risk of endometrial, gall bladder, cervical, ovarian, and breast cancer in women (1). Signs and symptoms of these disorders, such as vaginal or rectal bleeding, should be identified by the physician.

Table 23-2 Drugs that Can Promote Weight Gain (and Alternatives to Them)

| Category | Drugs That May Promote Weight Gain | Alternatives |

| Neurology and psychiatry | Anti-psychotics Antidepressants Lithium Anti-epileptics | Ziprasidone Buproprion, Nefazodone Topiramate, Zonisamide, Lamotrigine None currently available |

| Steroid hormones | Hormonal contraceptives Corticosteroids Progestational steroids | Barrier methods of contraception Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents Weight loss for menometrorrhagia |

| Diabetes treatments | Insulin Sulfonylureas Thiazolidinediones | Metformin Acarbose, miglitol Exenatide, pramlintide, liraglutide |

| Antihistamines | Diphenhydramine, cyproheptadine, others | Newer agents, inhaled steroids |

| B-adrenergic blockers | Propranolol, Metropolol, Atenolol, others | Carvedilol, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, calcium-channel blockers |

Obstructive sleep apnea is another disorder often overlooked in obese patients. Symptoms and signs include very loud snoring or cessation of breathing during sleep, often followed by a loud clearing breath and then brief awakening. The patient may be a restless sleeper; some find that they can only sleep comfortably in the sitting position. Many patients are completely unaware of any symptoms of sleep apnea. The patient’s partner may best describe these symptoms. Daytime fatigue, with episodes of sleepiness at inappropriate times, and morning headaches, also occur. On physical exam, hypertension, narrowing of the upper airway, scleral injection, and leg edema secondary to pulmonary hypertension may be observed. Laboratory studies may show polycythemia. If a patient’s history reveals any signs of sleep apnea, referral to a sleep specialist is appropriate. The onset of sleep apnea is sometimes associated with further weight gain. The successful management of sleep apnea helps the patient to feel more alert and focused and may assist with weight loss for that reason, or may change levels of weight-regulating hormones.

Drugs that Cause Weight Gain

A number of medications are known to cause weight gain in some patients (Table 23-2). These include antidepressants, phenothiazines, lithium, glucocorticoids, progestational hormones, over-the-counter antihistamines, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, and insulin, among others. In some cases, it may be possible to prescribe alternatives to these medications that will not cause weight gain.

A variety of medications can interact with, or cause side-effects if taken with a sympathomimetic appetite suppressant. The medications of concern include, but are not limited to: monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressants, over-the-counter weight control products containing synephrine, and other non-specific sympathomimetics.

Physical Examination

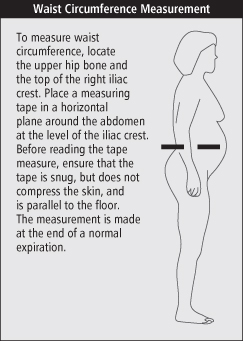

Clinical manifestations, causes and complications of obesity should be sought during the physical exam. Height and weight should be measured and the BMI calculated, waist circumference should be assessed with a tape measure (Box 23-1), and blood pressure should be checked with an appropriately sized cuff. One should be alert for manifestations of hypothyroidism and provide a thorough examination of the thyroid. In addition, special attention should be given to skin tags around the neck and axilla and acanthosis nigricans, which suggest hyperinsulinemia. Leg edema, cellulitis, and intertriginous rashes with signs of skin breakdown may be seen in the very obese.

Box 23-1 Measuring Waist Circumference

To measure waist circumference, place a measuring tape in a horizontal plane at the level of the iliac crest—the area just above the hip bone and below the ribs—without compressing the skin. The value is read at the end of a normal expiration. Men with a waist circumference > 102 cm and women with a waist circumference > 88 cm are at higher risk because of excess abdominal fat and should be considered one risk category above that defined by their BMI.

National Institutes of Health. The practical guide: identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health; 2000 (5).

Signs of type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hepatic steatosis, coronary heart disease, osteoarthritis of the lower extremities, gallbladder disease, gout, colorectal and prostate cancer in men, and endometrial, gallbladder, cervical, ovarian, and breast cancer in women should be sought.

Laboratory and Other Testing

Type 2 diabetes, gout, hyperlipidemia, and hepatic steatosis are the disorders most often discovered. Other lab test values may indicate disorders that may be involved in the induction of obesity and require specific treatment, such as hypothyroidism and hyperinsulinemia. Complete evaluation might include a complete blood count, urinalysis, and blood tests for glucose, uric acid, BUN, creatinine, ALT, AST, total and direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, and thyroid stimulating hormone. In some cases, a two-hour postprandial glucose and insulin level are of value in diagnosing hyperinsulinemia. At present, serum leptin levels and genetic studies are research tools. Measurements of body composition using methods such as bioelectrical impedance, while motivating to some patients, are not necessary for treating the average obese patient.

Evaluation

Risk Assessment

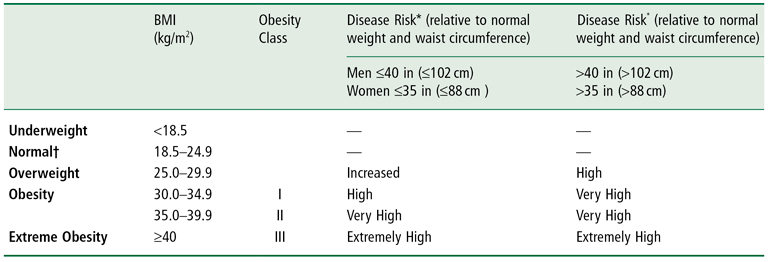

The risk associated with a given degree of overweight and obesity can be estimated using Table 23-3.

Table 23-3 Classification of Overweight and Obesity by BMI, Waist Circumference, and Associated Disease Risk*

Adapted from Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic of Obesity. Report of the World Health Organization Consultation of Obesity. WHO, Geneva, June 1997 (1).

*Disease risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and CVD.

†Increased waist circumference can also be a marker for increased risk even in persons of normal weight.

Contraindications to Treatment

Obesity treatment is contraindicated during pregnancy, as well as in patients in the terminal stage of an illness. Medical or psychiatric illnesses must be stable before weight reduction is initiated. Patients with cholelithiasis and osteoporosis should be warned that these conditions might be aggravated by weight loss.

Readiness to Lose Weight

The decision whether to attempt weight-loss treatment should involve consideration of the patient’s readiness to make the necessary lifestyle changes. This includes assessment of 1) the patient’s reasons and motivation for weight loss; 2) previous attempts; 3) expected support from family and friends; 4) understanding of risks and benefits; 5) attitudes toward physical activity; 6) time availability; and 7) potential barriers, including financial limitations, to the patient’s adoption of change.

For the patient to succeed, he or she must be ready to make the effort to lose weight. An unwilling patient rarely succeeds, frustrating the practitioner and alienating the patient. If the patient does not wish to lose weight and is not at high risk, weight maintenance should be encouraged. If the patient is at high risk as a result of obesity, the clinician should make an effort to motivate the patient by discussing the medical consequences related to the patient’s case. It should be noted that negative and pejorative statements should be avoided since they have no therapeutic value and tend to be demoralizing. The proper approach is termed “mutualistic”—the physician and the patient teamed together, tackling the disease.

Management

Goals of Treatment

The ultimate goal of treatment is weight loss followed by long-term weight management. The prevention of weight gain is the minimum goal. Given our current state of knowledge and the available treatments, keep in mind that the goal of treatment should be the lowest weight the patient can comfortably maintain. For the average patient, a realistic weight loss goal is about 5–10% of total body weight or 2 BMI units. Attaining an “ideal” body weight, or a loss of 20–30% or more of total body weight, is not possible for the vast majority of overweight and obese people. Even though many may feel disappointed when they are unable to reach their “dream weight,” they should be reminded that a loss of 5–10% of body weight can significantly improve risk factors associated with obesity because of the loss of abdominal fat (5). With this in mind, counseling about achievable goals and health-related goals such as an improvement in lipids or glucose, improved mobility, reduced waist circumference, or simply compliance with healthy eating are worthy alternative goals. Improvements in health complications should be discussed on an ongoing basis. If patients are focused on the medical benefits rather than the cosmetic benefits of weight loss, they may be better able to attain and maintain their goals and experience the feeling of success long-term. The typical rate of weight loss is 0.5–1 kg a week, but will vary from patient to patient. Faster rates of weight loss do not achieve better long-term results. Prevention of weight gain is another important treatment goal, often overlooked by patient and clinician, yet worth emphasizing.

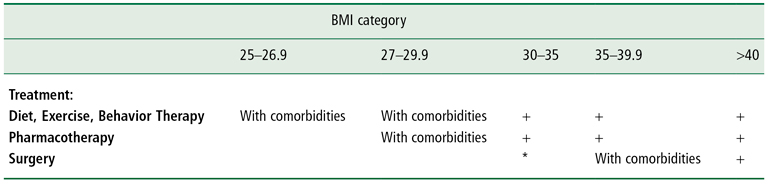

Deciding on Treatment

While healthy eating and an increase in activity should be encouraged in every patient, these are imperative for those with a BMI greater than 25, especially in the presence of comorbid conditions. More specifically, Table 23-4 outlines a guide to selecting the appropriate therapy based on BMI. Treatment, including the use of pharmacotherapy, is recommended for patients with a BMI > 30. It is also recommended for patients with a BMI of 27 or higher with concomitant obesity-related risk factors or diseases. Individuals at lesser risk should be counseled about the benefits of lifestyle changes.

Table 23-4 A Guide to Selecting Treatment

Source: National Institutes of Health. The practical guide: identification, evaluation and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Bethesda MD: NIH publication No. 00 4084 (5).

+: the treatment is recommended for individuals in that BMI category, with or without comorbidities.

With comorbidities: the treatment is recommended for individuals in that BMI category with comorbidities.

Prevention of weight gain with lifestyle therapy is indicated in any patient with a BMI >25, even without comorbidities, while weight loss is not necessarily recommended for those with a BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2 or a high waist circumference, unless they have two or more comorbidities. Combined intervention with a low-calorie diet, increased physical activity, and behavior therapy provides the most successful therapy for weight loss and weight maintenance.

*On February 16, 2011, the FDA announced approval of the LAP-BAND® Adjustable Gastric Banding System for use in obese adults with a BMI of 30–40 kg/m2 with one or more obesity-related comorbidity, and when nonsurgical weight loss methods have not been successful.

Behavior and Lifestyle Change

Behavioral techniques are not used alone, but in conjunction with all other approaches, including diet, exercise, medication, or surgery (5, 6) in order to achieve the best results. The goal of behavioral therapy is to overcome barriers to compliance. Behavioral therapy assumes that patterns of eating and physical activity are learned behaviors that can be changed, and that to change these patterns over the long term, the patient’s environment must be modified. In some cases, behavioral therapy is administered on an individual basis; in other cases, as group sessions. The combination of treatment modalities appears to be the key to achieving and maintaining maximal weight loss. A study that compared sibutramine (now removed from the U.S. market) use alone with lifestyle modification alone, and with a combination of sibutramine and lifestyle modification, found that the combination induced 5–6 kg more weight loss after 52 weeks of treatment (7).

Physical Activity

Physical activity is a key component of any weight management program because of its role in increasing energy expenditure, which is markedly reduced with weight loss (8). Clinical studies suggest that physical activity is more effective for preventing weight regain than it is in facilitating weight loss (9). Aerobic exercise is usually recommended for weight management because of the large number of calories burned as well as the other health benefits achieved. Strength training may also be beneficial because it builds lean body mass and improves body composition. Adherence to a regular exercise program is associated with better outcome, possibly because it may improve dietary compliance or be a marker of better dietary compliance. The added benefits of exercise include enhancing self-esteem, reducing stress, and relieving depression.

Any physical activity that the patient enjoys and is willing to perform is recommended. For the completely sedentary patient, walking is often the best way to start. Patients with physical limitations secondary to arthritis or size may start with water exercises, bedside stretching, seated activities, or a program designed by an exercise physiologist or physical therapist. In general, 30–45 minutes of exercise 3–5 days per week is recommended, although more of a greater intensity may be better. Up to one hour daily with one day off a week is a reasonable maximum goal. Three 10-minute periods of activity yield about the same benefit as a single 30-minute period, and compliance with such a program is more achievable. Increasing physical activity during daily life, such as climbing stairs instead of taking an elevator, walking or cycling rather than travelling by car, and parking farther away from the entrance to the mall, can be effective and simple ways to add small periods of physical activity to a busy lifestyle.

Nutrition Therapy

A calorie deficit must be created in order to reduce body weight. This can be achieved by giving general recommendations for healthy eating, such as reducing sugar, starch, alcohol, and saturated fat or total fat intake, or by setting calorie guidelines. No single approach to diet works for everyone; the best approach is to customize the diet to make it more palatable to the patient. Patient preference plays an important role in dietary selection and compliance. Recent findings suggest that foods with a lower glycemic index (blood glucose rise per gram of food) may reduce food consumption later in the day (10) and foods with a lower calorie density (number of calories per gram), such as vegetables, appear to be more filling and may reduce overall food consumption (11). Higher-protein diets, long in disrepute, appear to produce weight loss and health benefits similar to those of low-fat diets. Liquid meal replacement diets such as Optifast, and Slimfast are of value in certain people who have a medical need to lose weight. Fad diets and other methods that promise a quick, easy way to lose weight distract the patient from the real task at hand. While almost any method of unhealthy dieting can reduce weight in the short run, the true test comes in the long term. Diets that are too drastic cannot be followed long term. Unfortunately, the patient too often bears the blame for the lack of success, perpetuating a cycle of failure.

Medication

Obesity is as much a metabolic, endocrine disorder as is diabetes, and as such deserves medical and surgical management in clinically appropriate settings (1, 12). In general, medication helps patients to comply with a reduced-calorie regimen. Not every patient responds to a given medication. Currently, orlistat (Table 23-5) is the only prescription drug approved for long-term use by the Food and Drug Administration (see Chapter 18). However, several medications approved for other indications have been shown to cause weight loss and are included in Table 23-5 (12, 13). In addition, antihyperglycemic agents, such as metformin, exenatide, liraglutide and pramlintide, approved for the treatment of diabetes, appear to have beneficial effects on obesity and other cardiometabolic risk factors that comprise the metabolic syndrome. These agents have shown promise in reducing weight and improving abnormal glucose metabolism and therefore may help to prevent diabetes as well as cardiovascular disease. They should thus be considered first in the treatment of the patient with type 2 diabetes (2).

Table 23-5 Medications Used for Weight Loss

Source: ref. 13.

| Drug | Mechanism of Action | Side-effects |

| Sibutramine∧† | Appetite suppressant: combined norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Modest increases in heart rate and blood pressure, nervousness, insomnia |

| Phentermine*† | Appetite suppressant: sympathomimetic amine | Cardiovascular, gastrointestinal |

| Diethylpropion*† | Appetite suppressant: sympathomimetic amine | Palpitations, tachycardia, insomnia, gastrointestinal |

| Orlistat* | Lipase inhibitor: decreased absorption of fat | Diarrhea, flatulence, bloating, abdominal pain, dyspepsia |

| Bupropion∧ | Appetite suppressant: mechanism unknown | Paresthesia, insomnia, central nervous system effects |

| Fluoxetine#∧ | Appetite suppressant: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Agitation, nervousness, gastrointestinal |

| Sertraline#∧ | Appetite suppressant: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Agitation, nervousness, gastrointestinal |

| Topiramate∧ | Mechanism unknown | Paresthesia, changes in taste |

| Zonisamide∧ | Mechanism unknown | Somnolence, dizziness, nausea |

*Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for weight loss.

†Drug Enforcement Administration schedule IV. Medications with a limited potential for physical dependence. They are controlled substances for which a DEA number is required on a prescription.

#Have not been shown to produce weight loss for longer than six months and often produces weight gain thereafter.

∧Not approved or no longer approved by FDA for weight loss, but weight loss has been observed in clinical trials.

Sibutramine (Meridia®, Abbott Pharmaceuticals, Abbott Park, IL) was withdrawn from the U.S. market, in October of 2010, at the request of the FDA. It acts on the central nervous system to inhibit the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin (13–16). The drug was effective in that it amplified satiety signals and reportedly induced a sensation of feeling fuller more rapidly after the start of a meal. Sibutramine, while proven to be effective, was taken off the U.S. market because of concerns from the FDA regarding an increased risk of heart attack and stroke.

Health benefits demonstrated with the use of sibutramine included reductions in triglycerides, uric acid, total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol, and an increase in HDL cholesterol. Adverse events seen during randomized trials included dry mouth, constipation, insomnia, increased appetite, dizziness, and nausea. It was contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled or poorly controlled hypertension, congestive heart failure, symptomatic heart disease, coronary heart disease, conduction disorders, or stroke. Approximately 12% of patients treated with sibutramine had an increase in systolic BP of 15 mmHg or more; however, <1% of patients treated had to be withdrawn from trials as a result of a sustained increase in blood pressure. Of note, a decrease in blood pressure is most often seen in patients who lose more than 5% of body weight and in whom treatment would be most likely to continue. For these reasons, it was recommended that blood pressure and pulse be checked 2–4 weeks after sibutramine was started and then monthly for the first 6 months.

Orlistat (Xenical®, Hoffman LaRoche, Nutley, NJ) is an inhibitor of pancreatic lipases and prevents the absorption of about one-third of dietary fat ingested during a meal (17). Health benefits demonstrated in clinical trials include a reduction in LDL and increase in HDL cholesterol, reduction in blood pressure and fasting insulin levels, improvement in oral glucose tolerance test outcomes, and improved glycemic control in obese diabetics. The gastrointestinal side-effects associated with orlistat use are usually mild in intensity, occur early in treatment, and may enhance compliance with a low-fat diet. No effect on mineral balance or gallstone or renal stone formation was seen. A mild reduction in the levels of vitamin D and beta-carotene was noted in some treated patients during trials, and supplementation has been recommended with a daily multivitamin (taken several hours either before or after the drug is taken). Orlistat in a lower dose of 60 mg three times daily was recently approved by the FDA as an over-the-counter drug marketed as Alli® (Glaxo Smith Kline Pharmaceuticals, UK) in conjunction with a behavior modification program. (See also Chapter 18.)

Surgery

Bariatric surgery should be considered in patients with a BMI > 40 or between 35 and 40 who fail other methods of treatment, if serious obesity-related complications are present (5, 18–20). Subject to the same requirements, on February 16, 2011, the FDA announced approval of the LAP-BAND® Adjustable Gastric Banding System for use in obese adults with a BMI of 30–40. Careful screening of candidates is required if the patient is to benefit from the procedure. Surgical candidates must be motivated and well informed about the risks of the procedure, as well as the change in their lives that will occur as a result of the procedure and its long-term effects. These changes include the need for long-term treatment with vitamin and mineral supplements, modified food intake, and the possibility of chronic vomiting or diarrhea after meals. In general, weight loss of 20–50% of initial body weight is achieved depending on the procedure, and loss reaches its maximum at 18–24 months, with some weight regain up to the fifth year postoperatively and weight stability thereafter. Obesity surgery is best performed in specialty centers with experience in performing procedures on high-risk obese patients. Long-term follow-up is required to ensure the best weight loss and health benefit, and maintenance of proper nutrition over the long term. Surgery is discussed in more detail in Chapter 19.

Monitoring

In general, healthy patients on a weight-loss regimen should be seen in the medical office within 2–4 weeks of starting treatment in order to monitor both the treatment’s effectiveness and any potential side-effects. Visits approximately every 2–4 weeks are sufficient during the first three months if the patient has a favorable weight loss and few side-effects. Clinical judgment will dictate whether more frequent visits are required, particularly if the patient has comorbid conditions. The patient should be weighed at each visit, with waist circumference measured less often. Blood pressure and pulse should be monitored if the patient is taking an appetite suppressant. Each visit should be used to monitor compliance with the program, provide encouragement, and set new goals. This can be accomplished by reviewing food and exercise records, discussing progress (or lack of progress), and solving any problems the patient has encountered. Less frequent follow-up is required after the first six months.

Resources Available to the Healthcare Practitioner

The use of other healthcare providers with an interest in obesity treatment, including dieticians, psychologists, nurses, and nurse practitioners, is an efficient way to manage the obese patient. For example, while many physicians feel uncomfortable prescribing a diet, community or hospital-based dieticians are available in most communities to assist with patient education and support. For the clinician interested in treating obesity in the office, important educational information, including sample diets and other patient material, can be found in the NIH publication Practical Guide to the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults, or on the NIH/NHLBI website (www.nhlbi.nih.gov/nhlbi/cardio/obes/prof/guidelns/ob_home.htm). Obesity.org, the website of The Obesity Society (TOS), also contains educational materials and slides.

Conclusion

Obesity is associated with hormonal and metabolic changes that promote inflammation and chronic disease, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Lifestyle intervention is the first-line approach to the management of obesity. The process of assessment, classification, and treatment of obesity is like the evaluation and treatment of any chronic disease. For patients who cannot achieve weight loss or favorably modify their metabolic risk factors with lifestyle intervention alone, adjunctive long-term pharmacotherapy or, in some severe cases, bariatric surgery may be indicated. A goal of 5–10% body weight loss is achievable with non-surgical treatments and will improve obesity-related health outcomes. Chronic treatment is required, and relapse can be expected if treatment is discontinued.

Summary: Key Points

- Barriers to obesity treatment in the primary care setting include: practitioner training, not feeling comfortable providing treatment, perceiving treatment as ineffective and time-consuming, viewing the patient as responsible for the problem, and lack of reimbursement for treatment.

- Conditions that might contraindicate weight loss treatment in the primary care setting include eating disorders, substance abuse, alcohol abuse, current pregnancy, terminal illness, or the presence of unstable medical or psychiatric disease.

- The readiness of the patient to initiate a weight loss plan, which generally includes calorie reduction and physical activity, should be evaluated, and realistic, achievable weight-loss goals established. Where appropriate, use of medication or surgery should be considered.

- Monitoring of patients on a weight-loss regimen by a primary care physician can include periodic visits at which measurements may be made of weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, pulse, and compliance. Food and exercise records can be reviewed, new goals set, and problem-solving approaches discussed.

- Bariatric surgery should be considered in patients with a BMI >40, or between 35 and 40, if serious obesity-related complications are present.