Furthermore, their recommendations updated the 1998 definitions (6), replacing “at-risk for overweight” with the term “overweight” to describe children with BMIs from the 85th to the <95th percentile, and replacing “overweight” with “obese” for those at or above the 95th percentile (5). The earlier terminology had been intended to ease concern that the label “obese” would worsen children’s negative feelings about body size, trigger insensitive remarks from peers and families, and fuel the cultural stigmatization of fat people. Although success and self-esteem are still strongly linked to body image at an early age in the US and in many other cultures, the 2007 Expert Committee urged early identification and treatment in the spirit of preventing the unhealthy and often painful lifelong psychological and physical consequences of obesity.

One purpose of early assessment and intervention is to promote parental awareness of children’s excess weight, a particularly crucial step in tackling childhood obesity, as emphasized in a 2007 Institute of Medicine report (7). Still, some argue that overzealous efforts to raise awareness and trigger motivation among both parents and their children may not be effective and could even have undesirable consequences, leading to body dissatisfaction and unhealthy methods of controlling body weight (8).

We have a long way to go to achieve these recommendations. In practice, reported rates of documented diagnosis, referrals for care of comorbidities, and weight treatment among overweight children in clinical settings are very low (9–10). The overarching question is: If identification (documented diagnosis) leads to referrals (comorbidity screening) and screening indicates that treatment is necessary, what next? What treatment? What evidence exists for success, and what are the obstacles to successful intervention?

Promoting Parental Recognition of Overweight and Obesity

Parental awareness of children’s excess weight is a particularly crucial step in tackling childhood obesity. Yet some research strongly indicates that parents are poor judges of overweight in themselves and their children (11). Studies of parents report that from 32% (15) to 90% (16) of both overweight and healthy-weight parents do not recognize that their overweight child is overweight. Recognition and concern differ among cultural groups regarding children’s size and related health risks. In 2000, Young-Hyman and colleagues (12) reported that only half of African American parents perceived their overweight child as overweight, and of those who did, fewer than half (43%) considered obesity a health risk, even in families with a history of obesity and its complications. Among Native American children, whose rate of obesity is the highest of any group of US children, only 15% of parents and other caregivers (mainly grandmothers) recognize excess weight or associate it with future risk of disease (13). Latina mothers with children aged 2–5 years perceived smiling, sitting upright, and having healthy-looking skin and hair as more important aspects of health than weight. Thinness, in contrast to heavier weight, was perceived as poor health in children (14). Overweight parents are less likely to correctly categorize their overweight children as overweight. Still, among those with low recognition, 78% of parents say they are “quite” or “extremely” concerned about excess weight, regardless of parental weight status, about the same level of concern as for frequent sunburns or too much TV watching (15).

What accounts for this misperception? Focus group research finds that low-income mothers of overweight preschool children—mainly African American and Hispanic—commonly believe their children are “thick,” not overweight, and that children will grow into their weight. Further, many believe children are destined to be a certain weight which is impossible to change. Many think that eating healthy food compensates for high-calorie “junk” food, not realizing that large portions of even healthy foods come with excessive calories (16, 17). However, a 2006 study of African American and Hispanic children in Head Start programs found that minority mothers’ perceptions of their children’s body size may not be consistently biased in one direction. Despite the possible social norm for a larger body size among low-income minorities, some mothers of overweight minority children do perceive their children to be too heavy when they reach a certain size (18).

Targeting Behaviors Related to Childhood Obesity

The main behavioral approaches used in primary care are aimed at modifying diet and physical activity of individual children and families. Yet the Public Health 2005 Task Force also reported that evidence was weak, supporting the use of behavioral counseling to reduce childhood morbidity and improve psychosocial and functional measures (4). Nevertheless, recognizing the need for positive action, a 2006 National Institute of Health (NIH) Task Force concluded that, although the research base on how to prevent and treat is still limited, there is evidence that some interventions are effective when targeted to specific determinants of overweight (19). Building on this approach, a report resulting from an evidence-based analysis process was released by the American Dietetic Association (ADA) in 2006. It reviewed and recommended specific strategies for parents and children, as well as the effectiveness of specific counseling approaches for the healthcare provider (20). Recommendations from the ADA and the 2007 Expert Committee are summarized in Table 25-1. The conclusions about the strength of the evidence of the ADA are graded I, II, III, IV, or V (good to none); the Expert Committee recommendations were graded CE (consistent evidence), ME (mixed evidence), and a category that suggests they are unlikely to cause harm and are likely to have other benefits even if they do not support achievement of healthy weight.

Table 25-1 American Dietetic Association (ADA)* and Expert Committee (EComm)** Reviews of Target Behaviors Related to Childhood Obesity

The compilation of recommendations listed here represents those considered to be potentially effective and unlikely to do harm:

|

*The ADA conclusion statements result from the efforts of the ADA Childhood Overweight Evidence Analysis Work Group published online at the American Dietetic Association Evidence Analysis Library (EAL). Available at http://www.adaevidencelibrary.com. Accessed April 16, 2008.

**Expert Committee Recommendations on the assessment, prevention, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Barlow SE and the Expert Committee. Pediatrics 2007;120: Supp1–192.

Evidence for Specific Approaches to Modify Behavior

Only limited evidence is available to support the selection and promotion of specific approaches to reduce obesity rates in children. Typical findings on common approaches are summarized here.

Individual-Based Counseling Intervention

A 2002 physician-based, computer-interactive, individual counseling program (including nutrition and physical activity education) was compared to a standard care approach in overweight adolescents (21). Specifically, the program—a multiple-component, behavioral weight-control intervention (Healthy Habits)—was compared to a single session of weight counseling by a physician. Although the behavior change approach was feasible and well received by the adolescents, results did not differ in their effects on energy intake, percentage of calories from fat, physical activity, sedentary behavior, or problematic weight-related or eating behaviors/beliefs.

Another primary care office and home-based intervention with adolescents included computer-assisted diet and physical activity assessment, plus stage-based goal-setting, followed by brief healthcare provider counseling and 12 monthly mail and telephone counseling sessions. The same method was used with the comparison group, but it addressed sun-exposure protection. The intervention group significantly reduced sedentary behaviors and increased servings of fruits and vegetables, but no differences were seen in BMI (22). This trial (Patient-centered Assessment and Counseling for Exercise + Nutrition [PACE+]) was hailed as a “hopeful message that a primary-care-based intervention can result in some beneficial changes in children’s obesity-related behaviors,” despite the lack of an effect on BMI (23).

Family-Based Interventions

Based on weight loss or maintenance of reduction in weight/adiposity reports over 5–10 years, the ADA analysis concluded that there is sufficient evidence to recommend a family-based intervention including diet, physical activity, behavior change, and family counseling for reducing overweight in 5–12-year-old children (24). Weight reduction was reported in four studies by the same investigator (25–28). This intervention used intensive family strategies such as contracting, self-monitoring, and social reinforcement to limit consumption of fatty foods and to increase exercise. It involved a “traffic-light” or “stop-light” dietary plan based on food groups: Stop (Red), Caution (Yellow), and Go (Green). Green-group foods are low-calorie, high-fiber foods that may be consumed freely. Yellow-group foods are limited, but provide moderate nutrient density per calorie. Red-group foods are high in fat or simple sugars and are to be seldom eaten. The families studied were provided no-fee treatment (research funds were used), with assistance in monitoring food and activity patterns and learning to contract to earn rewards. The “Future of Children” summary report questioned widespread use of this intensive program, saying: “There is no evidence that it can be translated to primary-care centers—and implemented at reasonable cost” (3). However, the tools of monitoring, contracting, and reinforcement through group or individual follow-up are used frequently in diet counseling. Example forms are available for the 24-Hour Food Recall, the Daily Food and Activity Diary, and Goal Contract and Log from two ADA publications (29, 30). Other tools can be found/modified from resources for parents, teens, and children at the MyPlate website (www.choosemyplate.gov).

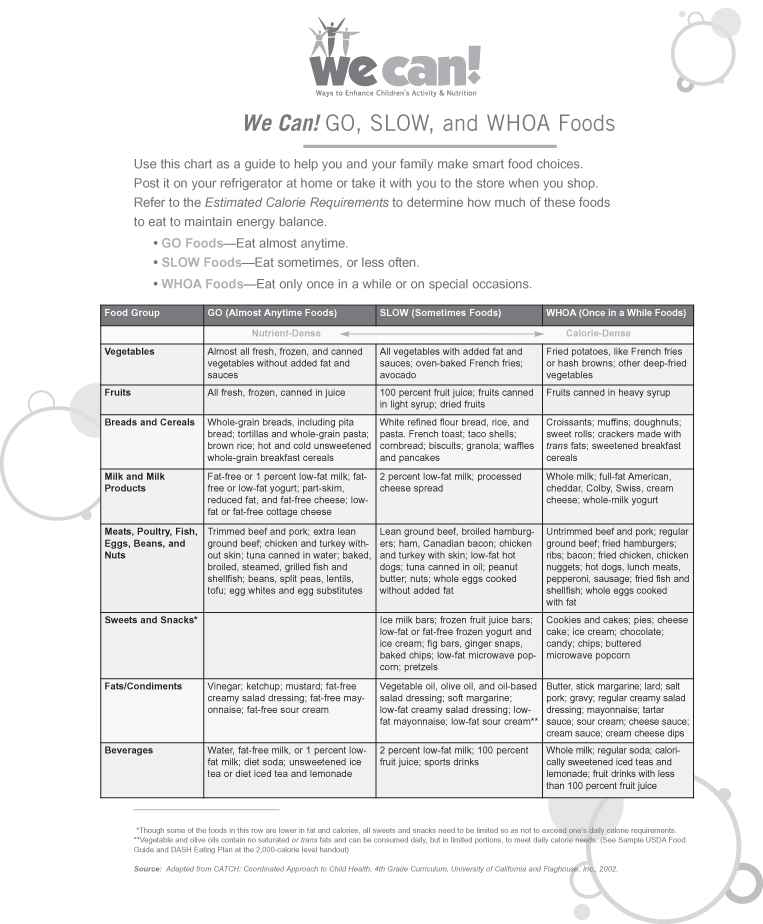

A similar family-based approach was used in the three-year Dietary Intervention Study in Children (DISC). This program relied on the application of motivational interviewing to modify diet, physical activity, and family behaviors. Over 300 children and their families engaged in an intensive intervention with dietitians and behaviorists during the first six months, including six weekly, followed by five biweekly, group sessions. Maintenance sessions were held 4–6 times per year during the second and third year, with monthly telephone contacts between group sessions. A “usual care” group of over 300 children was followed as a control group. DISC provides strong evidence for dietary intervention being successful for improvement of serum lipids, maintained over seven years through intensive family and child group strategies, but did not report a change in adiposity (which was not a goal of the study). The diet plan, tailored to lipid-lowering foods, was developed as a “Disc Go Guide” of concentric circles with “Go” foods at the center, “Slow” foods in the middle circles, and “Whoa” foods in the outer circles (31). These food groupings were adapted by the “We Can! Ways to Enhance Children’s Activity & Nutrition” NIH initiative and published in a Parent Handbook: Families Finding the Balance (32) (see Figure 25-2).

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing is a counseling technique that is applicable in most healthcare settings because it is delivered by a single trained health professional and is both useful and feasible to implement. An example is a six-month intervention program in a Scottish health center that actively engaged the child’s participation through adaptation of the traffic-light method and involved parents through motivational interviewing, goal-setting, behavioral contracting, and self-monitoring. It was implemented by a dietitian in a clinical setting and anticipated to have value for promoting healthful behavioral change (33).

Countering Resistance

Often, children and families are reluctant or resistant to trying new behaviors to improve their health and weight. In medical and dietetics practices, information typically is provided with the intent to persuade a patient to change. The clinician may say, “Drinking five cans of soda a day is one reason your child is gaining excessive weight.” Motivational interviewing assumes that behavior change is affected more by motivation than information, encouraging exploration of motivations and aspirations. Thus, the interviewer may say, “Some children who drink mostly water, instead of soda, stop gaining extra weight. What do you make of that?” A core principle of motivational interviewing is that individuals are more likely to accept and act on the opinions and plans that they voice themselves.

Motivational interviewing is a promising approach for counseling by healthcare professionals in pediatric weight management. The Healthy Lifestyles Pilot Study examined the feasibility and potential efficacy of motivational interviewing by pediatricians and registered dietitians in primary care pediatrics. Overall, the emphasis on “pulling” rather than “pushing” in motivational interviewing enabled clinicians to tailor interventions toward facilitating change in behavior among children and parents (34). Most participating parents reportedly agreed that the pediatrician/dietitian “listened to me, asked my opinion about things, asked permission before giving me advice, helped me think about why changing my family’s food or TV viewing habits is important, was supportive/encouraging, and discussed values that were important to me.” The idea is that the health provider empowers the parent or child to identify the lifestyle changes and to consider how to make the changes.

Another small, national, research-based study of office-based motivational interviewing showed promise in preventing childhood obesity. Parents of more than 90 overweight children, 3–7 years old, interacted in motivational interviewing sessions: one group as a control, another group in one session with a physician only, and a third group in four sessions—two with a physician, and two with a registered dietitian. At a six-month follow-up, BMI decreased the most in children whose parents were in the four-session group. The investigators called motivational interviewing “a promising office-based strategy” (35).

Parent Training

Parent training is a behavioral-counseling method in which parents are guided through a series of specific techniques to improve their parenting skills, including positive reinforcement, role modeling, and limit-setting. Evidence of effectiveness is inconsistent. Some studies report that counseling and educating parents (as opposed to the overweight children) is effective. Epstein and colleagues compared the change in weight of children with that of their parents after six months and again after 10 years. Children maintained the original weight reduction whereas parents did not (36). Similarly, Golan reported enhanced child weight loss when the parents as opposed to the overweight children, were targeted with counseling and education. The focus on the parents and siblings as well as the overweight child was more successful than singling out one child’s weight as “the problem” (37–38).

Maintenance of weight loss in overweight children is related to parents’ weight; weight loss was reported to be more likely to be maintained by children whose parents were both at a healthy weight (39). Overall, for the prevention of overweight in school-age children, the evidence supports using parent training in child-rearing techniques as part of a multi-component, family-based group intervention that also addresses diet, physical activity, and behavior, and includes family counseling. However, the evidence is limited for parent training having benefit in the absence of a multi-component program (24).

The Practice of Specific Approaches to Modify Behaviors

Role of Healthcare Providers

The diagnosis and treatment of childhood obesity requires the office-based clinician to translate the most effective, evidence-based research into daily practice. Cooperation is needed among all clinicians involved in the child’s and parents’ care, if they are to help the child and parents make lifestyle changes to improve the health of the entire family in the long term. An alliance developed with the family may also promote healthy weight management practices among parents and other family members (5).

Office-based clinicians generally do not have access to additional services of other professionals, such as behavioral therapists, dietitians, and exercise physiologists, who form the backbone of many of the academic center-based studies (3). Thus, clinicians have to use their clinical judgment and skills in providing guidance to both parents and the overweight child. In surveys, clinicians (pediatricians, nurse practitioners, and dietitians) reported that they viewed the obese child with concern and thought that intervention was important, but more than 50% did not know how to approach the problem, and many felt unprepared and ineffective in addressing it (40–41). Most clinicians felt they had insufficient time to dedicate to the obese child; this problem was compounded by lack of third party reimbursement for obesity treatment. They were also frustrated by their perception of insufficient patient motivation and lack of parental concern.

Another concern for clinicians is that the approaches in population-based studies may not be relevant because they focus on Caucasian, middle-class suburbia. How is a clinician in a large urban area going to apply those programs to their low-income population when many lack the support services needed to implement the recommendations? Despite these difficulties, some believe that successful treatment of childhood obesity will require a major shift in pediatric care, with pediatricians and other healthcare providers stepping up to take a major role in the care and health of the obese child (3).

The primary care provider is the first to identify and track childhood obesity as a problem with long-term consequences, and to coordinate services and referrals that the child and family may need. The Expert Committee (5) states that providers are responsible for considering current and future risks associated with obesity and rare conditions that cause obesity, and, because weight control alone may not treat many conditions adequately, that diagnosis must be followed by appropriate treatment. The following approaches address conditions associated with obesity in children (See also chapter 11).

Type 2 Diabetes

In 2000, the American Diabetes Association and American Academy of Pediatrics issued a consensus statement suggesting that children whose BMI is above the 85th percentile, who have a strong family history of type 2 diabetes, with signs of insulin resistance such as acanthosis nigricans, and who belong to an ethnic minority should be screened starting at puberty (42). A 2005 observational report noted that there appears to be a close relationship between presence of type 2 diabetes in adults and eventual appearance of this disorder in youth, and that the repetition of this pattern in many geographic regions suggests that attention to the epidemiology of type 2 diabetes in adults can help predict the emergence of type 2 diabetes in youth. These data may have implications for new screening programs to detect pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes, but most importantly, screening can help the implementation of obesity prevention programs in those specific regions (43).

Despite the large number of youth diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, treatment of this condition remains less than ideal. In many adults there is poor compliance with diet and/or weight control and in children we are seeing similar problems (44, 45). Until recently, insulin (which can only be given by injection) was the only FDA-approved medication for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in youth. The oral agents used as the gold standard of treatment in adults with type 2 diabetes appear to be efficacious in pediatric type 2 diabetes, but only one drug, metformin, is FDA-approved for youth. The long-term efficacy of oral agents is yet to be determined, but they are currently being studied in a nation-wide clinical trail, TODAY. Studies are also underway to treat with metformin high-risk youth with impaired glucose tolerance, in order to prevent onset of type 2 diabetes; long-term effects are as yet not determined (45). More effort is needed to prevent this condition, since the complications of this disease—including blindness, renal failure, leg amputations, stroke, and heart disease—can be devastating.

Acanthosis Nigricans

Acanthosis nigricans is a skin condition associated with obesity which can be used as a screening tool to identify patients who are insulin resistant and at high risk for type 2 diabetes since it is found in up to 90% of youth with type 2 diabetes. Once acanthosis nigricans is identified, the necessary screening can be done and measures taken to lower insulin levels and reduce the risk of associated diseases such as type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Weight loss and the consequent reduction in insulin levels can ameliorate acanthosis nigricans, and in some patients it can completely fade (46).

Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular Disease

The first-line treatment of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease is lifestyle modification, including exercise and a healthy diet low in concentrated sweets and fat, and high in fiber. Although no long-term evidence-based studies on children with these conditions are available, specific problems should be treated. For example, if elevated blood pressure is noted and lifestyle modifications fail to lower blood pressure, the patient will need blood pressure-lowering medication. The same is true for elevated cholesterol and impaired glucose tolerance.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

Treatment of PCOS is controversial. Over the last several years, a change has occurred in the treatment modalities. Previously, young women with PCOS were treated for prolonged periods of time with oral contraceptives, essentially to treat the menstrual irregularity and cosmetic symptoms (acne and hirsutism) associated with this syndrome. Currently, it is recognized that lifestyle modification should be the first line of therapy for all women with PCOS. Although there are no evidence-based guidelines for weight management for patients with PCOS, recent studies have shown that the hormonal, metabolic, and reproductive abnormalities associated with the disorder can improve with lifestyle modifications, suggesting that environmental factors play a fundamental role in susceptible individuals (47). Metformin is the currently preferred insulin-sensitizing drug for chronic treatment of PCOS and has been shown to be both effective and safe in adults and adolescents, although not FDA-approved for this indication. Metformin improves the metabolic profile, menstrual cyclicity, and infertility in women with PCOS, and is associated with weight loss in some, especially when combined with lifestyle modification (48). This is true even in normal-weight women with PCOS.

On the other hand, oral contraceptive use, even at low doses, may worsen the cardiovascular risk, as it can increase triglyceride levels and may worsen insulin resistance and induce glucose intolerance in some patients (49). Oral contraceptives have a place in the treatment of these young women, and many will also need them for contraception, but lipid profiles and glucose tolerance should be periodically assessed.

Promising clinical data show that with treatment (lifestyle modification and metformin) the development of abnormal glucose tolerance can be slowed and diabetes can be prevented. A study of adolescents with PCOS and impaired glucose tolerance who were treated with 850 mg of metformin twice daily showed normalization of glucose tolerance in eight of 14 of the girls treated (50–51). Others have shown that lifestyle intervention is effective for improving fertility with and without metformin (47).

Role of Parents and Other Caregivers

Parent and adult caregiver food preferences, the quantities and variety of foods in the home, eating behavior, and physical activity patterns all work in concert to establish an environment in which obesity can be promoted in the household (38). Parental obesity significantly increases the risk of obesity in adulthood for both obese and non-obese children, especially those less than 10 years of age. Those 1–2-year-old children who have an obese parent, and especially those who have two obese parents, appear to be susceptible to obesity in young adulthood (52). In the same way that cholesterol screening is recommended for children with a family history of hyperlipidemia, children born into a household with obese parents and obesity-related morbidities should be viewed as being at high risk for future obesity and its related morbidities. An alliance must be developed with the family, and in many instances parents must also be treated.

The 2007 Expert Committee recommends that clinicians encourage parents and other caregivers to promote healthy eating patterns by 1) providing only nutritious snacks; 2) increasing the availability of fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy foods, and whole grains; 3) encouraging children’s autonomy in self-regulation of food intake; 4) setting appropriate limits on choices; and 5) modeling healthy food choices (5). In a recent study, greater maternal nutrition knowledge and increased weight loss resulted from an eight-week intervention program for low-income mothers that promoted a better nutritional environment in the home; it also benefited the children (52).

Goals of Treatment for All Children

The aim of weight reduction/maintenance should be to decrease morbidity rather than to meet a cosmetic standard of thinness, and overweight children should be encouraged to set reasonable goals. Lifestyle alterations, in the form of increased exercise and/or decreased calorie intake, will need to be continued indefinitely if lower body weight is to be maintained. The primary goal of obesity treatment is improved long-term physical health through permanent healthy lifestyle habits—a good intervention outcome regardless of weight change. The second goal for overweight and obese children is gradual weight reduction/maintenance to decrease morbidity.

Even the most successful weight-loss programs in adults can only achieve a loss of 10–15% of total weight (53). Thus, the pressure to lose a certain amount of weight by a certain time can complicate matters, even if the patient has a lot of excess weight. A more productive approach focuses on weight maintenance; once this is achieved, the person can then work on weight-loss strategies. Maintaining weight requires a lot of effort; when a child is still growing, maintaining weight, if only for a year or two, is actually losing weight. When they stop growing, children who avoid further weight gain are setting the stage for making more permanent lifestyle changes that can promote future weight loss.

The 2007 Expert Committee proposed a systematic approach that integrates several aspects of treatment that are supported by evidence, although the approach as a whole is as yet untested. These recommended stages of progressively more intense obesity treatment are: 1) Prevention Plus, 2) Structured Weight Management, 3) Comprehensive Multidisciplinary Intervention, and 4) Tertiary Care Intervention (see Table 25-2). The suggested implementation may require identifying more resources, such as pediatric dietitians or behaviorists, training staff to conduct diet and activity assessments, and seeking more community resources.

Table 25-2 2007 Expert Committee Treatment Recommendations*

| The 2007 Expert Committee recommendations encourage a staged-treatment approach for children 2–18 years whose BMI is above the 85th percentile. This four-stage approach incorporates nutrition education, physical activity, parent training/modeling, and behavioral counseling. Progression through the stages is determined by the subject’s response to a given stage. If desired weight is not achieved in one stage, the next stage is undertaken. |

Stage 1: Prevention Plus

|

Stage 2: Structured Weight Management

|

Stage 3: Comprehensive Multidisciplinary Intervention

|

Stage 4: Tertiary Care Intervention

|

*Expert Committee Recommendations on the assessment, prevention, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Barlow SE and the Expert Committee. Pediatrics 2007;120: Supp1–192.

Although many of the counseling and behavioral therapy principles that apply to adult obesity treatment also apply to Stage I of childhood obesity treatment, the treatment plan needs to be individualized for the child and the family’s lifestyle, and should include dietary changes, increased exercise, decreased inactivity, and behavior modification. Children require special consideration. Because children are still growing, 1–2 years of weight maintenance can effectively compensate for each 20% increment above desirable body weight (54). As in adults, behavioral techniques have been used to help children lose weight (see Chapter 15). Self-monitoring is an important element in all behavioral programs. Understanding the balance between what we consume and expend is crucial for understanding why weight is gained and for making changes to stop weight gain and eventually to lose weight. Stimulus control, limiting the amount of high-calorie foods kept in the house and controlling where and why food is eaten, is useful. In many instances, children and adolescents eat because they are bored, not because they are hungry. They need to learn how to recognize fullness and hunger, modify their eating habits, and eventually change their attitude about food. Choosing health over taste, which requires self-understanding and maturity, is a very difficult task even for an adult. Exploring these issues with the child is important. Changes can be made, but this is often a struggle and it can take time to accept, attempt, and fully implement changes (55).

Infants and Toddlers

For the very young child, the focus is on the caregiver who controls food selection, preparation, and availability. The AAP recommends encouraging, supporting, and protecting breastfeeding for as long as possible, as some studies indicate a greater decrease in risk of obesity with prolonged breastfeeding. It is easier to overfeed using formula because it takes less effort to drink from a bottle than from the breast. Therefore, parents need to resist the urge to finish feeding a bottle when the baby shows signs of being full. Fruit juice consumption should be limited to less than 4 oz a day (even if 100% juice), in order to avoid replacing breast milk, formula, or water with a calorie-dense fluid. Water is strongly recommended for hydration of young children. Although infants and toddlers tend to prefer fruits and sweeter vegetables, the introduction of a wide variety of foods should be encouraged. Fat need not be restricted in an infant’s diet, but by age 2 years, a toddler requires only 30–35% of daily calories from fat. Encourage as much activity as possible (see www.aap.org).

Pre-School and Elementary School Children

Although school-age children are still under the control of a caregiver, they are more opinionated and can influence what they consume. One approach recommended by Golan for this age group is to consider the parents as the exclusive agents of change for the treatment of childhood obesity (37, 38). In these studies, because the focus was on the parents’ behavior rather than the children’s, greater behavioral changes were achieved, resulting in weight loss or preventing further weight gain. The researchers assumed that the presence and availability of unsuitable foods in the home was one of the main obstacles the overweight child faced. They encouraged parents to be both firm and supportive, to assume a leadership role with regard to environmental change, with appropriate granting of autonomy to the child. Of note, the obese children in this study did not know the treatment was targeted at them, as all children in the household had height and weight measurements at each visit. The researchers concluded that in some instances omitting the obese child from active participation in the health-centered program might be beneficial for weight loss and for promotion of healthy lifestyle among obese children. These data suggest that the stigma of obesity treatment in this age group may be counterproductive.

Teens

When adolescents are treated, better outcomes result when the intervention is directed to both the teen and parents, but not necessarily at the same time. The teenage diet is often unbalanced. Most adolescents do not get 5–6 servings of vegetables and fruits per day, and their diet is low in calcium as sugar-sweetened beverages have largely replaced milk (56). Teenagers often eat 10 of their 21 weekly meals outside the home, and most of these are eaten in school; teenagers are less likely than younger children to eat breakfast. A large portion of high school students use unhealthy methods to lose or maintain weight. A nationwide survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that, during the 30 days preceding the survey, 12.3% of students went without eating for 24 hours or more; 4.5% had vomited or taken laxatives; and 6.3% had taken diet pills, powders, or liquids without a clinician’s advice (57). Thus, it is important to elicit the teen’s concerns about health, body image, and weight-related behaviors, to explore possible choices, and, finally, to support the teen’s choice of selected healthful behaviors.

Useful Approaches for Health Providers, Families, and Children

Weight management is a family affair. Physicians and dietitians, working together, can provide assistance, rather than advice, by providing information and support based on the readiness of family members to try small steps. Begin by reviewing the family’s lifestyle, such as family activity, television viewing patterns, and patterns of food and meal planning, preparing, and eating. Use a positive attitude, explaining main goals in small, concrete steps. Describe each new behavior as a step, not as the final outcome. For example, expand and explore new food choices instead of concentrating on the foods to avoid. In one study, parents who had an overweight child and were in the preparation/action stage of change believed that their own weight was above average, perceived that their child’s weight was above average, and perceived that their child’s weight was a health problem (55). Assessment of such beliefs is important because it helps evaluate the parents’ readiness to help their child achieve a healthier weight.

Dietary Intervention

Dietary recommendations for overweight and obese children and adolescents are based on the foundation of sufficient protein, essential fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals, and limited saturated fat (58, 59). Mild calorie restriction in children has been shown to be safe and effective, when combined with a modified feeding behavior program aimed at both families and children, such as the traffic light diet (26). To lose weight, adults are often encouraged to eliminate up to 500 kcal from their daily diet. In contrast, calorie restriction is not always recommended for children because it can potentially interfere with growth and development. However, The ADA Childhood Overweight Evidence Analysis Work Group reviewed the efficacy of several balanced macronutrient dietary approaches and concluded (20):

- There is good evidence (Grade I) to support the use of a low-calorie diet (900–1,200 kcal/day) as part of a clinically supervised, multi-component weight-loss program for reducing adiposity among 6–12-year-old children.

- There is good evidence (Grade I) supporting the use of a reduced-calorie diet (no fewer than 1,200 kcal/day) in the acute treatment phase for obese adolescents ages 13–18 who are medically monitored for short-term weight improvements.

Treatment strategies combine the approach of decreasing the use of calorie-dense foods, such as fried foods, chips, etc., with the addition of more fruits and vegetables to the daily diet. The substitution of water for non-nutritious, high-calorie, sugar-sweetened beverages may be effective in some cases. Reductions in calorie-dense foods and sugar-sweetened beverages through substitution and/or elimination can decrease calorie intake and weight, without changing the general pattern of food consumption in the family (see Box 25-1).

Box 25-1 Actions to explore, explain, and empower

Using non-directive questions and reflective listening, determine which actions match the child’s and family’s values. Some approaches are:

- Choose substitutes wisely—replacing soda with iced tea or juice does not reduce calories; choose water or a no-calorie drink.

- Eat breakfast—identify quick meals to prepare and eat on the go.

- Apply the traffic light—or Go, Slow, and Whoa (see Figure 25-2) choices to menus when eating out—try sharing portions of fries and large servings of other calorie-dense foods with family or friends.

- Learn the amount of fat in popular foods like double burgers, potato chips, and fries, and the amount of sugar in soda, juices, and sports drinks from Tip Sheets with comparison examples.

- Learn portion sizes from Tip Sheet diagrams with common size comparisons, such as a tennis ball, cell phone, etc.

- Practice reading food labels. Compare serving size, total fat, and total carbohydrate content of favorite high-fat and high-sugar foods with alternative choices. (Parents and children with poor reading and math skills, and even many with higher education, struggle to interpret food labels (63).)

- Plan a shopping list with the whole family. Negotiate choices regarding the type and amount of calorie-dense food available at home for snacks.