N

%

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

SAH

83

47

SAH and IVH

38

21.8

SAH and IPH

29

16.7

SAH and IVH and IPH

24

13.8

Location of aneurysms

ACOM

79

45.4

ICA (non PICOM)

50

28.7

MCA

23

13.2

PICOM

22

12.7

Fisher grade

1 (No hemorrhage evident)

2

1.2

2 (SAH <1-mm thick)

27

15.5

3 (SAH >1-mm thick)

51

29.3

4 (SAH with IVH and/or IPH)

94

54

WFNS scale (Glasgow Coma Scale, GCS)

I (GCS = 15 without motor deficit)

31

17.8

II (GCS = 14–13 without motor deficit)

48

27.6

III (GCS = 14–13 with motor deficit)

58

33.3

IV (GCS = 12–7)

36

20.7

V (GCS = 6–3)

1

0.6

Vasospasm (Krylov)

0 (none)

31

17.8

I (<50 % narrowing in 1–2 segments)

53

30.5

II (>50 % narrowing in 1–2 segments)

28

16.1

III (<50 % narrowing in >2 segments)

42

24.1

IV (>50 % narrowing in >2 segments)

20

11.5

We treated a total of 174 patients with a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. The majority had isolated SAH (N = 83; 47 %). Thirty-eight (21.8 %) also had intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), 29 (16.7 %) also had intraparenchymal hemorrhage (IPH), and 24 (13.8 %) also had both IVH and IPH. The most frequent location of a ruptured aneurysm in our population was in proximity to the anterior communicating artery (ACOM; N = 79; 45.4 %). This was followed by the internal carotid artery (ICA; N = 50; 28.7 %), the middle cerebral artery (MCA; N = 23; 13.2 %), and the posterior communicating artery (PICOM; N = 22; 12.7 %).

The majority of our patients, 54 %, presented with Fisher grade 4 (SAH with IVH and/or IPH). The least number, 1.2 %, had no visible hemorrhage on CT but had SAH determined by lumbar puncture. As many of our patients presented with a good WFNS scale [I (N = 31; 17.8 %) or II (N = 48; 27.6 %] as presented with a poor WFNS clinical scale [III (N = 58; 33.3 %), IV (N = 42; 24.1 %) and V (N = 1; 0.6 %)]. Most of our patients presented with angiographically detectable vasospasm (N = 143; 82 %). Approximately one-third had extensive vasospasm (Krykov III and IV; N = 62; 35.6 %). A small number of our patients did not demonstrate vasospasm (N = 31; 17.8 %).

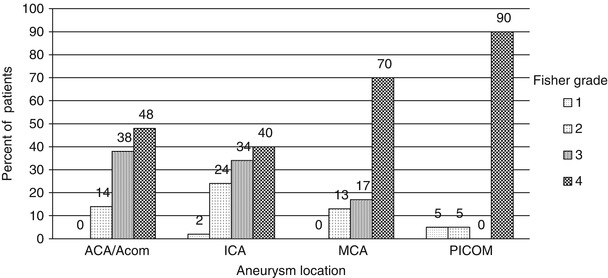

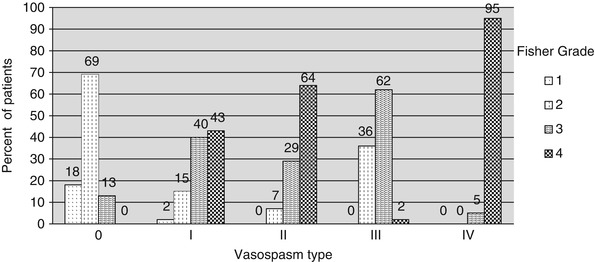

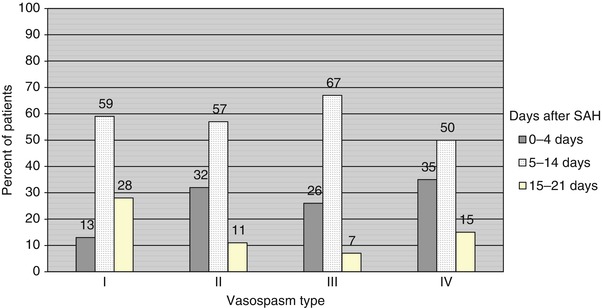

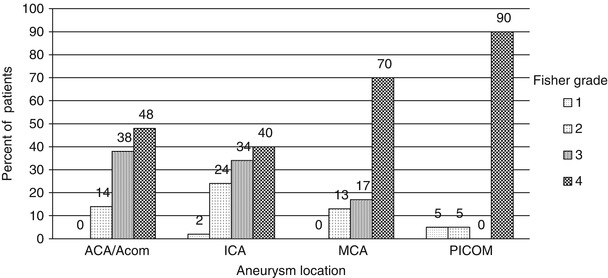

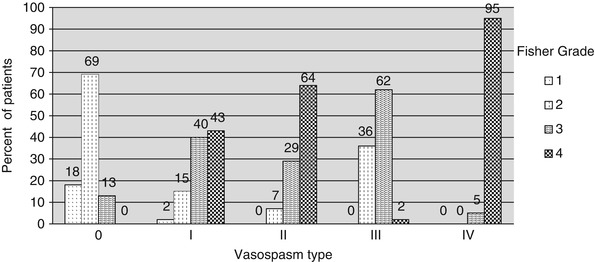

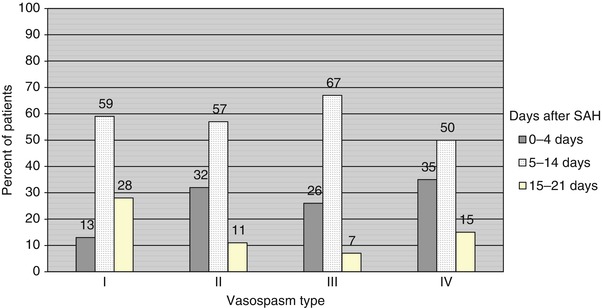

We analyzed the relationship between the location of a patient’s ruptured aneurysm and their Fisher grade (Fig. 1). We found that, for all locations, a Fisher grade of 4 was most common. We found this most prominently with MCA and PICOM aneurysms. We examined the relationship between a patient’s Fisher grade and their development of vasospasm (Fig. 2). Not unexpectedly, the patients with the most significant vasospasm (Krylov IV) had the highest Fisher grades. We studied the relationship between the severity of vasospasm and the days after SAH (Fig. 3). All severities of vasospasm were most commonly found in the 5- to 14-day period after SAH.

Fig. 1

Relationship between aneurysm location and Fisher grade

Fig. 2

Relationship between vasospasm severity and Fisher grade

Fig. 3

Relationship between severity of vasospasm and days after SAH

Management and Outcomes (Table 2)

Table 2

Management and outcomes

N | % | |

|---|---|---|

Aneurysm treatment | ||

Complete occlusion | 131 | 75.3 |

Complete occlusion withpreservation of parent vessel | 119 | |

Complete occlusion withoutpreservation of parent vessel | 12 | |

Subtotal occlusion | 29 | 16.7 |

Partial occlusion | 10 | 5.8 |

No occlusion | 4 | 2.2 |

Vasospasm | ||

Initial | 124 | 71.3 |

Delayed | 29 | 16.7 |

None | 21 | 12.0 |

Treatment of vasospasm | ||

Medical treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| ||