Treatment-Resistant Depression

BORIS BIRMAHER

DAVID A. BRENT

KEY POINTS

The main aim of treatment is to achieve remission and not only response.

No or partial response to treatment is commonly encountered in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder.

Before considering a patient a partial responder, nonresponder, or treatment resistant, it is imperative to evaluate all potential factors (individual, patient, family, other environmental) and clinicians’ specific factors that may contribute to the patient’s poor response.

Promote and assure adherence to psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy during the acute and maintenance phases of the treatment.

The management of a depressed child or adolescent who partially responds or does not respond to treatment should included education, psychotherapeutic, psychopharmacologic, and sometimes other biologic interventions.

Psychoeducation that promotes parental and child hopefulness in the context of realistic expectation about treatment is warranted.

Each new treatment needs to be done methodically and carried out step by step.

The first step is to optimize the current treatment by increasing the dose and/or increasing the length of treatment. If the patient does not respond or tolerate the treatment, consider switching or augmentation strategies depending on the case and preferences of child and family.

In general, for partial responders, augment treatment with a different class of antidepressant, other type of medications (e.g., lithium or triiodothyronine [T3]), or psychotherapy.

The only RCT for adolescents who did not respond to a single treatment with a SSRI showed that the combination of a different SSRI plus CBT was the best next strategy.

Monitor side effects, give hope, and include parents as co-therapists. This may reduce dropouts, which are common among treatment-resistant cases.

Manage comorbid disorders and give patients and their families the tools to manage and cope with ongoing family, school, friends, and other environmental stressors.

To improve the child’s outcome, encourage parents to seek treatment for their own psychopathology.

Treating difficult cases is hard on clinicians who can become disheartened and may benefit from seeking advice or support from colleagues.

Introduction

Pediatric major depressive disorder (MDD) is a recurrent familial psychiatric illness that causes significant disruption to the child’s normal psychosocial development and continues into adulthood. MDD is usually accompanied by interpersonal, academic, behavior, and occupational problems, as well as a high risk for substance abuse, legal problems, suicidal behavior, and completed suicide.1, 2, 3 Therefore, the proper treatment of pediatric depression can have a profound impact on the depressed youth’s developmental trajectory.

As described in Chapters 6, 8 and 9, current randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and psychotherapy (mainly cognitive behavior psychotherapy and interpersonal psychotherapy) alone or in combination are efficacious for the acute treatment of children and adolescents with MDD.4,5 However, at least 40% of depressed youth do not respond or do not show an adequate clinical response to these interventions. Moreover, only up to 30% show complete symptomatic remission to acute treatment. Consequently, a substantial proportion of depressed youth remain symptomatic despite exposure to adequate first-line treatment, with considerable impairment in their psychosocial functioning and with increased risk for suicide, substance abuse, behavior problems, and subsequent episodes of major depression.

This chapter discusses the definition, associated factors, and management of youth with “treatment-resistant depression.” Because there are very few pediatric treatment-resistant depression studies, the adult literature is cited, but treatments found efficacious for the management of treatment resistant depression in adults may not apply to youth. In this chapter, the term youth, unless specified otherwise, applies to both children and adolescents.

Table 4.1 (and reference 3) describe current definitions of response, partial response, remission, relapse, and recurrence. However, several studies have used their own definitions of outcome. For example, it is routine in pharmacologic studies to define remission by certain cutoff scores in a clinician-based rating scale, without taking into account the length of time the subject has been with minimal or no symptoms.

DEFINITION OF TREATMENT-RESISTANT DEPRESSION IN PEDIATRIC MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

Given the consequences of diagnosing a child with treatment-resistant depression, it is important to have a clear definition of this condition. However, as noted earlier, existing acute RCTs have shown that up to 50% of depressed youth fail to show significant clinical response to treatment and only a third show complete remission. Can we call these children treatment resistant after only one treatment, or do they need at least two trials with two antidepressants at standard doses for an appropriate period of time? Do the two antidepressants need to be from different classes or the same class? Finally, how should treatment resistance be defined in youth treated with psychotherapy?

These questions require further investigation. Furthermore, to diagnose a patient as nonresponsive or treatment resistant, the field needs to be in agreement about the definition of an adequate pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy treatment. For example, based in some, child and adult RCTs, an adequate treatment of depression with antidepressants has been defined as at least 8 weeks of treatment, at least 4 of which are at the equivalent of 20 mg of fluoxetine per day, and the second 4 weeks at an increased dose, failing an earlier response. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 However, recent adult studies have recommended 6 weeks of treatment before increasing the dose and at least 12 weeks of treatment.13 “Adequate” psychotherapy appears to require the implementation of one of two interventions for which there is some empirical evidence for efficacy, namely cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal therapy (IPT), at a “dosage” of 8 to 16 sessions, for a complete course of treatment.5,14, 15, 16

The only existing RCT for depressed adolescents who did not respond to a trial with a SSRI, the Treatment of SSRI-Resistant Depression in Adolescents study (TORDIA),8 defined treatment-resistant depression or no response as a clinically significant depression: Child Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R)17 total score ≥40 and a Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S)18 subscale ≥4 (at least moderate severity)—despite one appropriate pharmacologic treatment. TORDIA did not evaluate treatment resistance to psychotherapy. However, the “dosage” of psychotherapy in clinical trials of either CBT or IPT in depressed children or adolescents ranged from a low of 5 to 8 sessions of CBT to 12 to 16 individual or group sessions in other studies of CBT and IPT. 14, 15 16,19 Therefore, a reasonable minimum adequate “dose” of evidence-based psychotherapy is approximately 8 to 12 sessions. Longer-term follow-up of psychotherapy studies indicates that even among those who initially respond, many require additional booster sessions or additional types of mental health services, or they experience relapses, which again supports the view that even given “adequate” exposure, many depressed youth will require additional intervention. 20, 21, 22

In summary, there is not clear agreement regarding the definition of treatment resistance. Some experts have defined “treatment-resistant depression” as failure to respond to an adequate course of treatment with an antidepressant or psychotherapy. However, given that in child and adolescent MDD acute RCTs, the response rate to either antidepressants or psychotherapy is around 60%, this would be defining a very high proportion of patients as “resistant.” Some might argue that treatment-resistant depression should be defined after failure to respond to 12 weeks of combination therapy (e.g., CBT plus a SSRI)—which would include 30%, still a large proportion. Thus, until these issues are resolved, the following working definition of treatment-resistance in routine clinical practice is proposed:

A youth whose symptoms of MDD and functional impairment persist after:

8–12 weeks of optimal pharmacological treatment consisting of:

At least 6 weeks of 20 mg of fluoxetine per day (or an equivalent dose of an alternative SSRI)

Dose subsequently increased, depending on tolerance, for another 4 to 6 weeks.

And a further 8 to 12 weeks of an alternative antidepressant or augmentation therapy with other medications or evidence-based psychotherapy.

OR

8 to 16 sessions of CBT or IPT

And a further 12 weeks of pharmacologic treatment consisting of:

At least 6 weeks of 20 mg of fluoxetine a day (or an equivalent dose of an alternative SSRI)

Dose subsequently increased, depending on tolerance, for another 4 to 6 weeks.

Treatment could be more aggressive in severe cases treated in specialist settings, particularly if the life of the patient were at risk. In all cases, these treatments are complemented with patient and family education, support, and case management.

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH POOR OR NONRESPONSE TO TREATMENT

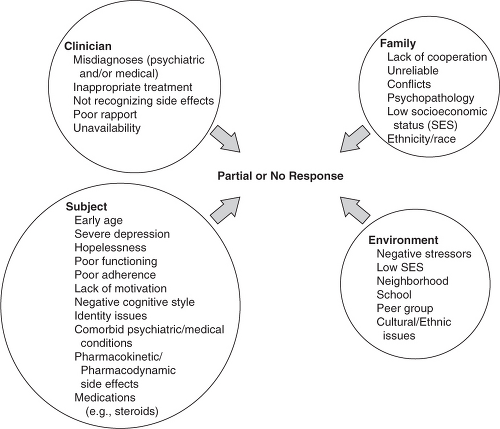

Given the high rate of partial or nonresponse to the existing treatments in youth, it is helpful for clinicians to have a framework to help them determine the particular factors contributing to treatment failure or resistance in each patient and guidelines on how to intervene and increase the likelihood of remission. 1,2,10 Even though these factors overlap, for simplicity’s sake they are divided into clinician, individual, family, and other environmental factors. Although nonexhaustive, Figure 16.1 shows some of the common variables associated with no or partial response.

INDIVIDUAL

Individual factors associated with no or partial response include, among others, early age of onset, hopelessness, low psychosocial functioning, poor motivation toward treatment, or poor adherence (for factors associated with poor adherence, see Chapter 15). In the case of medication, this means incomplete adherence to the prescribed regime. When patients are treated with medications with shorter half-lives, such as sertraline, skipping dosages can result in withdrawal symptoms, which in turn can be associated with clinical deterioration and further nonadherence. With regard to psychotherapy, patients are required to practice and apply skills learned within the session. Other predictors of poor response include indicators of severity (high symptom ratings of depression, suicidal ideation, low functioning), chronicity (long duration), and complexity (e.g., presence of psychosis or comorbid conditions such as disruptive behavior disorders, anxiety, eating, and substance abuse disorders), personal identity issues (such as concern about same-sex attraction), and socioeconomic factors (e.g., poverty and poorer response to CBT23). Also, use of other medications (e.g., steroids, contraceptives, interferon, and/or retinoic acid) and medical illness such as hypothyroidism, anemia, mononucleosis, folate or B12 deficiency and other chronic conditions can produce symptoms that overlap with the depressive symptoms or contribute to treatment nonresponse. Although relatively few studies have examined ethnicity and treatment response, there is some suggestion that IPT may have greater benefit in some domains than CBT for depressed Hispanic adolescents;24 conversely, response rates to CBT are better in Whites than in minority depressed youth.25 Hopelessness is

associated with both a poorer treatment response and dropout, at least in some psychotherapy trials.26,27 In addition, pharmacokinetic (e.g., absorption, rapid or slow metabolism, intolerance at adequate dosage) and pharmacogenetic (presence of certain polymorphisms, such as the less functional variant of the serotonin transporter) as well as medication side effects may contribute to poor response or poor adherence to antidepressant treatment.28

associated with both a poorer treatment response and dropout, at least in some psychotherapy trials.26,27 In addition, pharmacokinetic (e.g., absorption, rapid or slow metabolism, intolerance at adequate dosage) and pharmacogenetic (presence of certain polymorphisms, such as the less functional variant of the serotonin transporter) as well as medication side effects may contribute to poor response or poor adherence to antidepressant treatment.28

CLINICIAN

Among the first issues a clinician should consider when a patient is not responding to treatment is the possibility of misdiagnosis (e.g., bipolar-II versus unipolar depression) or that the patient has an unrecognized or untreated comorbid psychiatric or medical condition (e.g., anxiety, dysthymia, ADHD, eating, substance use, personality disorder, early-onset schizophrenia) or is using medications that are contributing to depressive symptomatology. Because most youth with a bipolar diathesis present in their first episode as major depression, one of the most problematic differential diagnosis is between unipolar and bipolar depression. 1, 2, 3,29 However, the presence of psychosis, a family history of bipolar disorder, or pharmacologically induced hypomania may help the clinician suspect the presence of bipolar instead of unipolar depression. 1, 2, 3 Also, the presence of recurrent periods of elation, euphoria, and agitation above and beyond what it is expected for the child’s age and cultural background may indicate the presence of bipolar disorder.

Clinicians should also consider that the pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy offered is not appropriate or that the length or dosage is inadequate for the specific child who is not responding to treatment. The presence of unrecognized medication side effects or ongoing exposure to chronic or severe life events (such as sexual abuse or ongoing family conflict) should be taken in consideration. Finally, the clinician may be an inadequate fit with the child, has poor motivation to help, or poor skills as a pharmacotherapist or psychotherapist.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree