, Jeffrey R. Strawn2 and Ernest V. Pedapati3

(1)

Division of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

(2)

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA

(3)

Division of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry Division of Child Neurology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

There is no such thing as an analysand apart from the relationship with the analyst and no such thing as an analyst apart from the relationship with the analysand.

—Thomas Ogden

Attachment theory and infant developmental research have confirmed the ubiquitous nature of the innate bidirectional mode of communication that exists in everyday human interactions. From birth, the infant learns to make meaning of the experiences with its caregivers in order to develop internal working models of attachment that reflect implicit patterns of stable or unstable mental representations of self and others. When the internal working models of attachment are created in a secure and stable manner, it allows the child to understand and predict the intent of others in their environment, and it implicitly becomes a survival-promoting tool allowing for proximity with others, establishing a psychological sense of “felt” security (Bretherton 1985; Sroufe and Waters 1977). Further research has provided a better understanding of how cognitive and memory systems shape a person’s experiences when interacting with others in what are called moments of intersubjectivity —the dynamic interplay between two people’s subjective experiences (Chap. 5). Intersubjective experiences allow for “being with” and “getting” another person’s state of mind and their intentions. It is this dynamic interplay of subjectivity that, when things go well, leads to adaptive models of relating with others. These models are stored in nonconscious and nondeclarative memory systems in what is known as “implicit relational knowing ,” which begins to be represented before the availability of language (Lyons-Ruth et al. 1998). Intersubjectivity promotes a cohesive and more flexible way of reflective abilities to know what works for healthy social reciprocity with implicit aspects of morality. Rustin and Sekaer (2004) aptly observe: “Experience, in an average expectable environment, enables genetic programs to unfold and puts the fine tuning on the genetic framework. From this new perspective the brain itself is relationally constructed.”

Thus, the advances from attachment theory, infant developmental research, and intersubjectivity have helped recognize that problematic and unstable early attachment experiences have a role in the development of mental health problems in children and adolescents. As a natural result, two-person relational psychology emerged as a theory of the mind that provided a path for the application of concepts derived from attachment theory, infant developmental research, and neurosciences in the practice of psychodynamic psychotherapy. As such, the notion of a two-person relational model of psychodynamic psychotherapy shook the foundations of traditional one-person psychoanalytic theory. Holmes (2000) suggests that attachment theory’s “most significant contribution to contemporary psychoanalysis could be to help it accept the death of its founder…. Bowlby can help us let Freud go.” We suggest not letting Freud go, but rather acknowledging the important role he had in how two-person relational psychology evolved from the traditional one-person theories.

In two-person relational psychology , the psychotherapist takes an active role to first become an ally to the patient’s subjectivity and implicit relational knowing during the session. As Adler-Tapia (2012) states, “Psychotherapy needs to account for the significant contribution of early attachment to mental health and behavioral issues.” That is, the intersubjective experience becomes a construct of the patient and psychotherapist’s personalities—temperament, cognition, cognitive flexibility, and internal working models of attachment—brought into the context of a here-and-now therapeutic relationship. It is through this bidirectional process that allows the patient to implicitly, over time, become an ally to the psychotherapist’s healthier and more adaptive way of interacting with others. In essence, the psychotherapist provides a new emotional experience for the patient, which is stored in the patient’s nondeclarative memory at an implicit level.

In this chapter, we provide a review of the trajectory of two-person relational psychology to give the reader an in-depth understanding of the importance and applicability it has to the clinical work with children and adolescents in psychodynamic psychotherapy.

3.1 Two-Person Relational Psychology

Making the Case for a New Paradigm

Over the last 30 years, with the emergence of a two-person relational psychology, there has been a significant shift in the understanding of a person’s psychological problems, from intrapsychic and object relations conflicts to problems of temperament, cognition, affective attunement, cognitive flexibility, and intersubjectivity (the complex interactions of the self, influenced by other persons, detailed in Chap. 5). This shift has led to psychotherapeutic interventions that are significantly different than those of a traditional one-person model—the archaeological discovery of an unconscious conflicted buried past. A two-person relational model relies on open bidirectional, here-and-now subjectivities that are continually modified by the reality of both persons—intersubjectivity. As expected the notion of a two-person, relationally-based psychodynamic model of psychotherapy was not received well by all clinicians in the traditional one-person psychoanalytic circles, as it challenged the legitimacy of its tenets. Friedman (2010) reflects, “The chasm dividing classical and relational approaches is both wider and deeper than is acknowledged by psychoanalysts who attempt to either reconcile or minimize the differences between them.”

The two-person relational model has gradually become a concept that most psychodynamic psychotherapists must contend with. Spezzano (1993, 1996) suggests that “the phrase two-person psychology has become shorthand for our recognition that a new paradigm has taken a firm foothold in American psychoanalysis.” This method is widely spoken about in clinical circles, and many clinicians have found the freedom of being “authentic and real” with the patient as liberating from the traditional one-person approach. Two-person relational psychotherapy, in one form or another, is now practiced by a majority of mental health practitioners (Norcross et al. 2002). The two-person relational model has served as an umbrella for several forms of psychotherapies that endorse enactments and self-disclosures that frequently occur unknowingly, although at times can be well timed —mindfulness, dialectic, cognitive, patient centered, etc. Further, in the two-person relational model, the psychotherapist as an authentic and real person may implicitly disclose aspects of him or herself without quite knowing what has been revealed.

In spite of the appeal of the two-person relational model, we have had colleagues who over the years have outwardly moved toward a contemporary two-person relational approach in their clinical work, although in reality they continue to be loyal to traditional one-person theory concepts and technique principles (Chaps. 2 and 6). They cautiously share that they do not want to throw out the baby—traditional one-person psychoanalytic concepts—with the bathwater, traditional one-person psychoanalytic technique. We find an example of this dilemma in our colleague and friend, Andrew Gerber , illustrated in his commentary Neurobiology of Psychotherapy – State of the Art and Future Directions (Gerber 2012) in the outstanding book Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Research: Evidence–Based Practice and Practice–Based Research (Levy et al. 2012). Gerber is of the opinion that the intersection of neurobiological research and psychoanalysis “is fertile and growing…. That would have delighted Sigmund Freud.” He proposes four unifying principles. In the first, he suggests that the description of psychopathology lies in a set of continuous trait and state variables representing the content and structure of an individual’s mental life. In the second principle, Gerber asks for a conciliatory stance, inviting the traditional one-person model clinicians to make mend with their own struggles in accepting that “the origins of most psychopathology are understood best as an interaction between inherited/genetic factors that lead to psychological traits, strengths, and vulnerabilities on the one hand and environmental factors, particularly experience, on the other” (italics ours). As such, two-person relational psychologies always include two “one persons.” His third principle emphasizes that psychological processes are best understood as a combination of cognitive, affective, and social categories. Finally, in his forth unifying principle, he seems to plea to the traditional one-person psychoanalytic community to accept their limitations: “The mechanism(s) of action in psychotherapies of all kinds, including psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy, overlap more than current clinical theories describe, thus beginning to explain the widespread finding that there are multiple effective ways to treat psychiatric illness with talk therapy” (italics ours). Gerber is implicitly moving the psychoanalytic movement toward a more integrative process—“we now have the opportunity to integrate multiple perspectives in our theory and research”—in line with two-person relational psychology, and concludes with “It is the task of psychotherapy to help the patient find a set of narratives that are most useful for him or her. In psychodynamic thinking, this is often described as ‘co-construction ,’ whereas in cognitive therapy, it may be thought of as ‘cognitive restructuring.’”

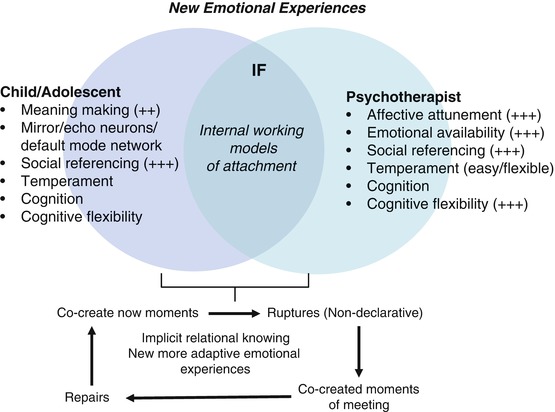

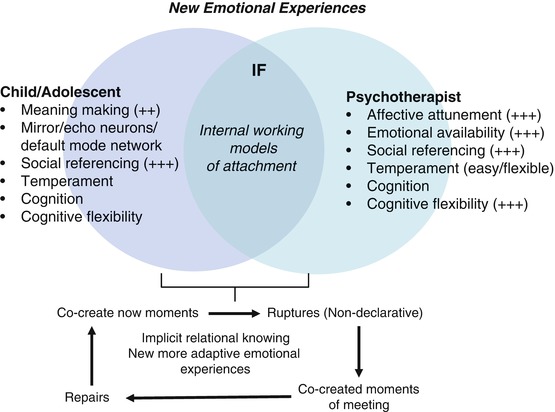

Although we mostly agree with Gerber’s principles and efforts for further dialogue among the divergent forms of psychotherapy, we caution his efforts toward an overly conciliatory stance with traditional one-person psychology clinicians as it attenuates the differences. The traditional one-person clinician believes that psychotherapy is effective when the inner conflicts of the child or adolescent are discovered and understood: through recognition of maladaptive ego defenses, the presence of transference manifestations (i.e., remembering and repeating), or by discovering object relations conflicts, which are amenable for being worked through by verbal insight-oriented suggestions or interpretations. Although the two-person relational psychology has built on the traditional one-person model, it has evolved to an approach that relies on the nonverbal, implicit cocreation of new experiences in the form of enactments and self-disclosures that frequently occur unknowingly, although at times can be well timed, to move along the psychotherapeutic relationship. The result of this is providing new and healthier nonconscious relational neuronal pathways in the here and now with the active and genuine psychotherapist—corrective emotional experiences—and later implicitly used when interacting with others (Fig. 3.1). Gaines (2003) suggests promoting new, more adaptive relational experiences, saying the “thoughtful use of therapist self-disclosure is an important tool for child and adolescent.” In two-person relational psychology, the terms “cocreate ” and “intersubjectivity ” are sine qua nons to the theory and technique. They reflect the active participation by both patient and psychotherapist in the encounter, with continuous and novel moment-to-moment changes due to each other’s subjective experiences.

Fig. 3.1

Schematic representation of two-person relational psychotherapy representing the psychotherapist and patient. New emotional experiences occur in the intersubjective field (IF), the overlap of subjective experiences. Number of (+) denotes degree of strength in this dyad

Altman (1994) masterfully captures the differences between the two models: “As I argue, child psychoanalysts of all schools has been moving in the direction of a relational, two-person or multiperson psychoanalytic model in response to the difficulties encountered in work with children on a drive theoretical basis. However, child analysts have done so while avoiding a clean break with drive theory. The result has often been a collage of one-person and two-person elements, which results in an internally inconsistent theoretical model with confusing implications for psychoanalytic technique. Specifically, a drive-based, one-person model directs attention away from the impact of the here-and-now interaction on patients.” As Hoffman (1994) states, “there is a feeling of ‘throwing away the book.’” We believe that is better stated as “let’s not forget that the original (one-person) book also has a second (two-person) part.” The mechanisms of therapeutic action may be different, but they still rely on an interaction of one and two person factors.

In Chap. 6, “Deconstruction of Traditional One-Person Psychology Concepts,” we take a bold approach that we believe is much needed but cautiously avoided by most. In that chapter, we discuss in detail the steadfast terms from traditional one-person psychologies, followed by their deconstruction when viewed through the lens of a two-person relational psychology. We then further clarify the reasons why these everyday traditional one-person concepts have transformed to terms that attend to discoveries from developmental research, neuroscience, attachment, and temperamental theories to the clinical work of a contemporary two-person relational psychotherapist.

3.2 Historical Background of Two-Person Relational Psychology in Adults

The origin of two-person relational psychology in adults dates back to the 1900s in Europe by Sigmund Freud’s dissenting colleagues and students. It is mostly believed that two-person relational psychology took hold in the United States during the last 30 years. Herein, we will briefly provide the reader with the historical evolution of the emergence of the two-person relational psychology model in the landscape of the adult psychotherapist, followed by the subsequent influence for the child and adolescent psychotherapist.

Freud’s Dissenting Colleagues

Freud began with a small and closed group of colleagues loyal to his psychoanalytic theories and formed the Wednesday Psychological Society, which later became the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. Among some of its members were Wilhelm Stekel, Paul Federn, Alfred Adler, Otto Rank, Sándor Ferenczi, Ian Suttie, Karl Abraham, and Carl Jung. Over time, conflicts aroused, and Adler, Jung, and Rank broke away from Freud’s drive theories and formed their own societies. This was followed by the departure of Ferenczi, Stekel, and Suttie, who introduced the idea that the analyst needed to be a real and active participant in the process in order to help the patient feel understood. Though their progressive ideas had the potential of extending the psychoanalytic movement to greater scientific inquiry, they instead were ostracized from prominent psychoanalytic circles for questioning Freud’s psychoanalytic theories and advocating changing neutrality to an empathic bidirectional relationship that allowed for gratifying the patient’s wishes in certain situations. The early dissenters provided the seeds needed to give birth to what later became two-person relational psychology.

Sándor Ferenczi (1873–1933)

Sándor Ferenczi was considered the heir to Freud’s Psychoanalytic Society (Fig. 3.2). He later became critical of Freud’s authoritarian and patriarchal stance, as well as his centerpiece of psychoanalytic technique, neutrality. Ferenczi encouraged a certain degree of flexibility and emotional availability of the analyst with the patient and encouraged the gratification of certain wishes in the form of empathy. In retrospect, it is clear that Ferenczi had set the stage for two-person relational psychoanalytic psychology to emerge. In Berman ’s (1999) masterful review of Ferenczi legacy, he states, “He was ahead of his time, and our generation finds him more understandable than his own.” Soon after, others in Freud’s circle openly agreed with Ferenczi’s view, the importance of the analyst as a real person and not as transference object, now considered the sine qua non in two-person relational psychology. Most of the dissenters from that period were strongly influenced by the work of Ferenczi, who pioneered the analyst’s authenticity, emphasizing the mutuality of the relationship between psychoanalyst and patient (Aron and Harris 1993). Both Ferenczi and Rank believed that therapeutic change occurred when the analyst provided supportive experiences rather than only by the interpretation of the transference.

Fig. 3.2

Sándor Ferenczi and Sigmund Freud (Image from The Sandor Ferenczi Center at The New School for Social Research (New York, NY)

For nearly a half century, the politics in the psychoanalytic community suppressed much of Ferenczi’s ideas; however, there has been a recent rediscovery about the importance of his work. In an excellent review of Ferenczi’s theoretical concepts and clinical practice, Rachman (1999) called him a “clinical genius of psychoanalysis.” Ferenczi was not simply deviating from his mentor, Freud; he was offering an alternative theory to understand the human mind. In his seminal work The Confusion of Tongue Between Adults and Children (1933), Ferenczi stated that negative early childhood experiences (e.g., parental depravation and empathic failures) could lead to adult psychopathology. Ferenczi’s contributions to psychoanalytic theory and technique include: (1) the introduction of empathy into the analytic relationship, (2) the importance of noninterpretative behavior by the analyst, (3) the function of experiential and emotional dimensions in the analytic therapy, (4) analyst self-disclosure, and (5) pioneering mutual analysis (Rudnytsky et al. 2000). To date, the first four contributions remain very much among the main tenets of the two-person relational model of psychodynamic psychotherapy.

William Stekel (1868–1940)

William Stekel was known as Freud’s most distinguished pupil (Wittels 1924). Stekel’s early contributions to psychoanalysis and child psychoanalysis while in Freud’s circle are described in Chap. 2. Subsequently, though, Stekel strongly criticized Freud’s analytic method: “Orthodox analysis, which demands that man remember all occurrences as far back as childhood, has set up an impossible task for itself—impossible to accomplish in the way it is being handled. We can call orthodox analysis the passive analysis (Stekel and London 1933). The analyst commands his patient to tell everything which passes through his mind. These revelations are then explained and associated. The same method is employed in the interpretation of dreams, Freud’s passive analysis.” Furthermore, he had strong words against Freud’s prohibition in giving advice to patients and believed it was necessary to assist pedagogically and to guide patients during the sessions. He said of Freud’s method, “No wonder that a treatment of this kind requires endless time and patience on both sides, on the part of the physician and that of the patient” (Stekel and London 1933). Stekel recognized that when the analyst took an active role during the analysis, the patients would feel safe and more open to reveal their conflicts.

Ian Suttie (1898–1935)

Ian Suttie posited that the infant had the innate capacities and wishes for human “companionship.” In his masterful and little known book The Origins of Love and Hate (1935), Suttie stated: “Formally, the tentative theory I have formed belongs to the group of psychologies that originates from the work of Freud. It differs fundamentally from psychoanalysis in introducing the conception for an innate need-for-companionship, which is the infant’s only way of self-preservation. This need, giving rise to parental and fellowship ‘love.’” Suttie was interested in the emotional bond between infant and mother and the impact it had on adult psychopathology. Montagu (1953) writes, “Where the cornerstone of the Freudian system is sex, in Suttie’s it is love.” Sadly, Suttie died at the age of 46, although the legacy of his work at the Tavistock Clinic in London later influenced John Bowlby, the father of attachment theory.

British Relational Theorists

Charles Rycroft (1914–1998)

It was not until the 1950s that Charles Rycroft , a British psychoanalyst, left the Freudian psychoanalytic movement of Europe and openly questioned the scientific credentials of psychoanalysis and became dismayed by the bitter rivalry between the Kleinian and Freudian camps (Rycroft 1985; Holmes 1998). He too questioned the psychoanalytic approach of the detached observer and emphasized the importance of the real relationship between the psychotherapist and patient as crucial and curative. Though he was also dismissed from traditional psychoanalytic circles, Rycroft reinvigorated the ideas of two-person relational psychology through his prolific work in popular press, including The Observer and The New York Review of Books.

Jeremy Holmes (1943–)

Jeremy Holmes is a contemporary British psychoanalyst whose instructive books The Search for the Secure Base: Attachment Theory and Psychotherapy (2001) and Exploring in Security: Towards an Attachment–Informed Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy (2010) make use of Bowlby’s concept of internal working models. Holmes proposed that psychotherapists need to take an active role in order to help adult patients break the negative cycle of self-defeating experiences. He believes that when patients and psychotherapists mutually cocreate a coherent new narrative of their experiences with others, they learn to manage their affects more effectively. He adds, “What good therapists do with their patients is analogous to what successful parents do with their children” (Holmes 2001).

American Relational Theorists

In the United States, there also were some dissenters who broke from the mainstream of Freud’s drive theory and the restrictive psychoanalytic techniques, specifically the emphasis on analytic neutrality and psychic determinism (Chap. 6). The dissenters founded the William Alanson White Institute (WAWI) in 1946. The WAWI was strongly influenced by the work of Ferenczi, and its members included Harry Stack Sullivan, Clara Thompson, Erich Fromm, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, David Rioch, and Janet Rioch. Currently, WAWI is one of the leaders in the advancement of two-person relational psychology and has among its faculty member’s distinguished writers Philip Bromberg, Jay Greenberg, and Donnel Stern.

Harry Stack Sullivan (1892–1949)

Harry Stack Sullivan is thought to be among the original important figures in American psychiatry. He departed from Freud’s drive theory and Klein’s object relations theory and was considered a Neo-Freudian psychiatrist and psychoanalyst whose main contribution to the psychoanalytic movement was the interpersonal theory and interpersonal psychotherapy. He proposed that the most important contributor to the formation of a person’s personality was the interpersonal relationships created in early childhood within the context of society and culture (Barton 1996). Sullivan believed that a person “can never be isolated from the complex of interpersonal relations in which the person lives and has his being” (Sullivan 1940).

Jay Greenberg (1933–) and Stephen Mitchell (1946–2000)

The shift from Freud’s one-person psychology to a two-person relational psychology occurred over several decades, and it was not until 1983—with the publication of Jay Greenberg and Stephen Mitchell ’s seminal book Object Relations in Psychoanalytic Theory—that the differences and overlaps between relational and drive models were outlined. Greenberg and Mitchell were trained under the influence of Harry Stack Sullivan, the founder of the interpersonal theory of psychiatry (Sullivan 1953). Greenberg and Mitchell’s (1983) departure from Freud’s traditional drive theory led to the distinct two-person psychology concept of relatedness—referring to the analyst and patient—that represented a change in psychoanalytic thought. They stated, “Relations with others constitute the fundamental building blocks of mental life.” The psychodynamic theories that ensued were a clear departure from the traditional one-person model that considered the neutrality of the analyst to be a necessary component in facilitating the development of the transference neurosis onto the analyst. The contemporary two-person relational psychology model proposes a bidirectional form of treatment that features the mutual participation of the psychotherapist and the patient in a real relationship, with attention to here-and-now cocreated moments that are recognized as therapeutic in and of themselves. Greenberg and Mitchell saw the relational models as diverging from the traditional Freudian conceptualization of human motivation and the nature of the mind. So as to not recreate bitter conflicts, such as those that Freud had with his dissenters or the heated disagreements between the Anna Freudians and the Melanie Kleinians, Greenberg and Mitchell were wise in taking a rather conciliatory approach when conveying their concepts to the psychoanalytic community (King and Steiner 1991). Ultimately, with Mitchell’s (1988) book Relational Concepts in Psychoanalysis: An Integration that the relational movement took hold in the United States.

By 1991, Mitchell had become the most prolific and influential relational psychoanalyst in the field and was instrumental in helping to launch the International Association for Relational Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy. He also became the founding editor of Psychoanalytic Dialogues: The International Journal of Relational Perspectives, which remains a well-respected international publication for the contemporary psychoanalytic and psychodynamic community. Sadly, Mitchell died at the age of 54, and in honoring his work, his colleagues founded The Stephen Mitchell Center for Relational Studies in New York City in 2010. It continues to be an active educational and clinical center that counts many well-respected two-person relational psychoanalysts among its faculty, including Lewis Aron, Beatrice Beebe, Jessica Benjamin, Adrienne Harris, James Fosshage, Paul Wachtel, and Jay Frankel. Pearlman and Frankel (2009) reflect on the relational movement, saying it “gained its first institutional foothold when it became a separate official ‘orientation’ within the New York University postdoctoral program in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis in 1988.” For an eloquent and detailed description of two-person relational psychology and attachment theory in psychotherapy of adults, we refer the reader to Buirksi and Haglund (2009), DeYoung (2003), Wachtel (2010), and Wallin (2007).

Paul Wachtel (1940–)

Paul Wachtel is a psychologist and psychoanalyst and cofounder of the Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Integration (SEPI). The central themes of his writings focus on the theory and practice of two-person relational psychotherapy, which he eloquently distinguishes from the traditional one-person model. He posits that what transpires during a psychotherapy session goes beyond the patient and psychotherapist subjectivities. He emphasizes that the clinical encounter is best viewed from a fully contextual approach: accounting for the patients’ and psychotherapist’s experiences of each other as implicitly being influenced by earlier relationships, as well as implicit social and cultural forces. He is best known for his books Relational Theory and the Practice of Psychotherapy (2008), Inside the Session: What Really Happens in Psychotherapy (2011), and Cyclical Psychodynamics and the Contextual Self (2014).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree