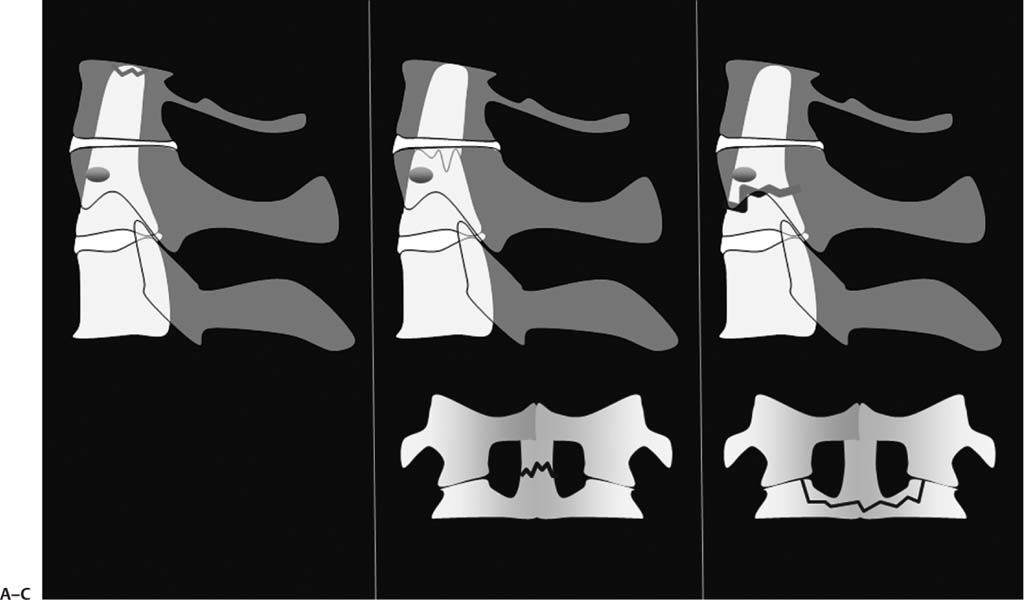

3 Odontoid fractures have posed a challenge to spine surgeons since they were first recognized in the early twentieth century.1 The incidence of odontoid process fractures has increased substantially within recent years, with current estimations indicating that they account for up to 15% of all cervical spine injuries.2,3 Odontoid fractures are traditionally classified using the system described by Anderson and D’Alonzo,4 with type II fractures (which occur at the waist of the odontoid process) found to be most common (Fig. 3.1).2,3,5,6 Unfortunately, type II odontoid injuries are often unstable and have a predisposition toward displacement and nonunion, especially in the geriatric population. Odontoid fractures occur most commonly as the result of falls or motor vehicle accidents and present in a bimodal age distribution in young adults and elderly patients.2,3,5,7 In the elderly, odontoid fractures represent the most common cervical injury in patients over the age of 70 years. These injuries are also the most common overall spine fracture in individuals over 80 years. Furthermore, as the North American population continues to age, the incidence of such fractures is predicted to increase. Historically, 50% mortality rates for odontoid fractures have been reported in the past, though modern advances in diagnosis and treatment have reduced the general rate to 4 to 11%.8 The mechanism of injury differs among the two bimodal groups most affected. In young patients, the injury is usually the result of high-energy trauma. In the elderly, the mechanism is typically a low-energy fall. Each presents a unique set of challenges to the treating spine surgeon. Younger individuals with odontoid fractures often present with associated injuries that complicate their care. Elderly patients are more likely to present with an isolated fracture, but medical comorbidities and lower functional reserves adversely impact outcomes. These disparate factors culminate in a relatively high complication rate for both populations, including permanent loss of function and, in some instances, death. Management options for odontoid fractures have expanded along with advances in imaging and surgical technologies over the last 25 years.3,7–10 The ideal treatment modality for such injuries, however, has not been established.3,7,9 This may be attributed to the absence of a scientifically rigorous, prospective investigation comparing treatment options.3,7 Additionally, it is difficult to fashion uniform treatment recommendations based on the current literature, which consists of mostly small, retrospective reports describing outcomes for disparate populations with substantial heterogeneity (Table 3.1). Potential treatments for patients with odontoid fractures include nonoperative external immobilization in a cervical orthosis, or halo vest, internal fixation via an odontoid screw, or atlantoaxial arthrodesis from a posterior approach. A rigid cervical orthosis can be used to immobilize nondis-placed odontoid fractures and facilitate healing. Due to the high pseudarthrosis rate associated with these injuries, however, many have advocated the use of a halo vest. Halo vest immobilization can also be utilized to maintain alignment in displaced odontoid fractures once they have been reduced. Posterior C1–C2 arthrodesis may be performed in most instances in which surgical treatment is indicated for odontoid fractures. Historically, a variety of procedures have been performed to effect posterior cervical stabilization. In recent years, the C1 lateral mass–C2 isthmus screw technique has gained popularity because it does not require preoperative reduction (as is needed with a C1–C2 transarticular screw) and can be used to intraoperatively reduce odontoid fractures (Fig. 3.2).9,10 Since its description in 1989, the potentially minimally invasive technique of anterior odontoid screw fixation has also gained popularity.11 An anterior odontoid screw enables direct osteosynthesis at the fracture site and potentially reduces the limitations associated with loss of head rotation.2,3,7,9,11 Fig. 3.1 The Anderson and D’Alonzo classification system for odontoid fractures. (A) Type I fractures are avulsions off the odontoid tip, while types II and III fractures represent fractures at the (B) waist of the odontoid and (C) C2 vertebral body, respectively. In terms of indications and optimal patient selection, however, most management options have been incompletely characterized, particularly in regard to the elderly. At the present time, the optimal treatment for these injuries remains controversial, and recommendations continue to evolve within the context and limitations of published reports. Specifically, controversy still exists regarding the choice of operative versus nonoperative management, the role of halo-vest immobilization, and the merits of anterior screw fixation versus posterior fusion. Table 3.1 Level of Evidence of Published Studies

Type II Odontoid Fractures: Operative versus Nonoperative Management

Level | Number of Studies | Study Type |

|---|---|---|

I | 0 | Prospective, randomized, controlled trial (0) |

II | 1 | Prospective series (1)29 |

III | 28 | |

|

| |

|

|

Operative versus Nonoperative Management

Operative versus Nonoperative Management

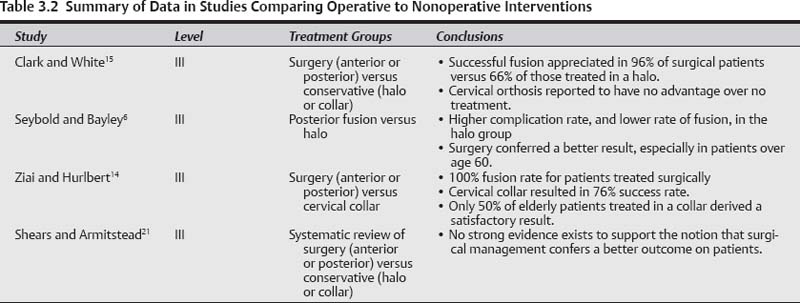

The level of evidence of comparative studies published in the literature is summarized in Table 3.2.

Level I Evidence

There is no level I evidence available regarding this topic.

Level II Evidence

There is no level II evidence available regarding this topic.

Level III Evidence

There is a variety of level III data evaluating the results of nonoperative management, and comparing outcomes between patients treated conservatively and those receiving surgery. Unfortunately, there are no prospective reports.

Govender et al reported outcomes in 183 patients with odontoid fractures treated solely with external cervical orthoses.12 The average age of the patients in this series was 36.7 years, and no patients were over age 65. Union was achieved in only 54% of those patients with type II odontoid fractures, but the presence of successful healing was not found to have an impact on clinical outcome.

Fig. 3.2 Lateral radiograph of a construct using C1 lateral mass–C2 isthmus screws for reduction and fixation of a posteriorly displaced odontoid fracture.

Koech et al examined results in 42 elderly patients (median age of 80) treated conservatively with cervical orthoses or halo-thoracic immobilization.13 Radiographic evidence of healing was present in 50% of patients treated in collars, whereas union was evident in only 37.5% of those immobilized in a halo-thoracic vest. Once again, radiographic union was not found to correlate with clinical outcome, and the authors affirmed that stability, as detected by flexion-extension radiographs, was present in 90% and 100% of those treated with cervical collars and halo vests, respectively.13

Greene and colleagues reported outcomes for 120 consecutive patients with type II odontoid fractures treated conservatively at a single center.5 In this cohort, with an average patient age of 41, the authors documented a 28% nonunion rate with conservative management. Comparable rates of healing have also been reported in the conservative treatment arms of several other studies, including those of Ziai and Hurlbert (24% nonunion rate),14 Clark and White (34% nonunion rate),15 Seybold and Bayley (35% nonunion rate),6 and Hanigan et al (45% nonunion rate).16 It is noteworthy that in the report of Clark and White nonoperative management in a cervical orthosis was found to have no advantage over no treatment.15

Several level III studies have also directly compared external immobilization with operative intervention. One of the earliest investigations was that of Clark and White, which investigated outcomes in 96 patients with an average age of 43 years.15 These authors found that anterior or posterior surgery resulted in a higher healing rate and fewer complications than immobilization in a halo vest. In this study, successful union was appreciated in 96% of patients treated surgically compared with 66% of those treated with halothoracic immobilization.

Seybold and Bayley reviewed outcomes in 37 patients treated with either posterior fusion or external immobilization for the treatment of their type II odontoid fractures.6 Complication rates and pain scores were found to be higher and fusion rates lower in those treated with a halo vest. Surgically treated patients also had better functional outcome scores, though not statistically significant except in those patients over the age of 60 years.6

Ziai and Hurlbert compared outcomes in 93 patients treated with operative or nonoperative management.14 Successful healing occurred in 100% of those patients who received surgery. Seventy-six percent of those managed nonoperatively went on to heal their fractures, although this value was found to be lower (50%) in patients over the age of 65. A similar pattern among geriatric patients has been appreciated in other studies as well,16–18 with older patients prone to a higher rate of nonunion, complications, and mortality, especially when treated with halo-thoracic vests.19,20 Furthermore, a recent investigation has documented a high complication rate as well as increased mortality among elderly patients regardless of intervention.18

In an effort to synthesize evidence-based recommendations from the available literature, Shears and Armitstead sought to conduct a systematic review comparing surgery with non-operative management as treatment for odontoid fractures.21 These authors were unable to identify any randomized or prospective investigations addressing the treatment of odontoid fractures. They concluded at the time of their writing that there was no strong evidence that surgical management of odontoid fractures confers a better outcome on patients.

Summary of Data

Currently no high-level evidence exists to support operative or nonoperative management as the ideal treatment for patients with type II fractures of the odontoid. Based on the limited data available, both external immobilization and operative fixation remain treatment options.5,7,12–21 Unfortunately, most investigations comparing operative to non-operative management have not utilized the most current surgical techniques. Although several studies document a higher fusion rate with surgical fixation, there is limited evidence that the presence of nonunion adversely impacts outcome.6,12 Halo fixation may be poorly tolerated in the elderly, with an associated high complication and mortality rate.19,20 Nonetheless, poor outcomes have been documented for elderly patients in multiple reports regardless of treatment modality.3,6,16–18

Pearls

• Operative and nonoperative interventions are both viable treatment options for patients with type II odontoid fractures.

• A higher fusion rate can be attained with surgical fixation.

• Complication and mortality rates are higher in elderly patients regardless of intervention.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree