OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Review emerging definitions of children’s health and changing epidemiology.

Define health development and discuss the impact of the social environment on health outcomes.

Identify protective factors for child health development.

Define health promotion and describe the Life Course Health Development Model.

Describe the unique vulnerability of children.

Identify strategies to transform the clinical practice to serve vulnerable children.

Summarize strategies to tailor clinic-based assessment, education, intervention, and care coordination to vulnerable children.

Xavier is a 2-year-old boy with delayed language development. His parents are immigrants from Mexico and speak to him in Spanish. He watches television 3 hours a day and reads with his parents two to three times per week. His parents describe him as a normal, healthy boy.

INTRODUCTION

Childhood is a critical and dynamic period of health development that has lifelong effects on health and well-being.1 Preventing chronic illness and promoting optimal long-term health require a special focus on optimizing health and overall functional capacity in childhood, investing in a child’s health potential and lifelong health reserves.

This chapter discusses emerging concepts of children’s health and highlights the relationships among health, health development, and health promotion. It proposes a framework for understanding health development over an individual’s lifetime2 and how pediatric health-care providers can promote health and prevent chronic illness in the child and the future adult.

EMERGING CONCEPTS IN CHILDREN’S HEALTH

The 2004 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Children’s Health, the Nation’s Wealth, defines children’s health as “the extent to which an individual child or groups of children are able to or enabled to (a) develop and realize their potential; (b) satisfy their needs; and (c) develop the capacities that allow them to interact successfully with their biological, physical, and social environments.”3 This definition of children’s health highlights the intimate relationship between health and human development and expands it to include not only physical but also social and mental well-being. Furthermore, this definition focuses not only on the individual child but also on groups or populations of children.

US child health ranks at the bottom among wealthy nations in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)/UNICEF rankings, partially explaining why the United States is the sickest of wealthy nations as measured by adult health outcomes.4,5 This is not surprising given that in just one generation, we have witnessed remarkable increases in child health problems, with over 30% of all children having chronic health conditions. Nearly 10% of all children report disabilities caused by health problems (up from 2% in 1960) and 22% of adolescents report diagnosable mental health conditions with impairments.6,7

The shifting epidemiology of child health has profound implications for how children’s health care should be organized and delivered. Prior to the 1970s, infectious diseases were the dominant threat to children. With advances in vaccine effectiveness and availability, as well as other public health improvements, the focus of clinical pediatrics in the United States has shifted to the prevention, identification, and management of chronic health conditions, such as asthma and obesity, as well as neurodevelopmental conditions, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, and depression.6,8,9 Despite this major shift in the epidemiology of child health, much of the organization of pediatric well child care continues to focus on the prevention of infectious disease and the provision of immunizations.10 A major challenge now is addressing the mismatch between the current way that children’s primary care is organized and the changing epidemiology of child health.10,11

Living in poverty has always been associated with greater exposure to adversity, more risks, and decreased access to resources including health care. The US social landscape was characterized by rising social mobility and a general trend of decreasing inequality for many decades (1910s-1970s).12 This created an atmosphere where the American Dream—that each generation of Americans would be better off than the previous generation—was an ostensible reality, and it supported a view that poverty was not a permanent life course exposure.

After nearly five decades of increasing social mobility, education expansions, and additional benefits provided by War on Poverty programs, child poverty rates were cut from 27% to 14% between 1960 and 1975.13 However, household poverty rates of families with children began to increase in the late 1970s and, other than a slight downturn during the 1990s, have persisted at high levels. Currently, 22% of children live in families whose income is below the federal poverty line (FPL), with almost half (45%) living below 200% FPL.12,14 Overall, the current lack of social mobility means that 40% of kids born into the lowest quintile of income (i.e., poverty) will continue to live below the lowest quintile their entire lives.15 This trend is especially concerning as a growing body of literature suggests most low-income families (i.e., living below 200% of FPL) do not have the economic resources nor the access to the services and supports that are necessary for their children to thrive.

With deeper social stratification and a steeper social gradient, even families that are still considered middle class are finding that they do not have the time and resources necessary to provide all the child rearing resources that their children need.16 Overall, with inadequate support for child care, early intervention services, and other child rearing supports commonly the norm in other nations, families also lack the services that they need to help their children thrive.17

HEALTH DEVELOPMENT AND IMPACT OF THE SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT ON HEALTH OUTCOMES

Health development is a term that further expands the definition of health to acknowledge childhood as a unique period in which biological, behavioral, and environmental influences intertwine to influence current and future (adult) health.2,18,19 For example, in children with asthma, environmental exposures (e.g., dust mites, smoke) cause chronic inflammation and ultimately change lung structure and function, which has implications for adult lung function and adult functional capacity. Interventions improving children’s health thus can potentially prevent lifelong chronic illness.

Health development also defines health in terms of functional capacity. In so doing, it recognizes that health is a dynamic state that is influenced by multiple determinants, from genes to the environment with which they interact.2 For example, a poorly nourished child from a low-income family who is exposed to violence and attends school in an overcrowded classroom may not reach his developmental potential and is at greater risk for anemia, injuries, and behavioral problems. If these result in lower educational achievement, the path out of poverty becomes more difficult to follow.

Recent data highlight the relationship between low SES/poverty and brain development, including areas such as the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, providing a biological explanation for how environmental stressors associated with poverty “get under the skin” and have lasting impacts on functional outcomes.20,21,22,23,24 For example, “toxic stress” can affect a child’s developing midbrain and interrupt affiliation and attachment capacities, affect the prefrontal cortex, and interfere with the development of optimal executive function. This results in decreased impulse control, which affects not only interpersonal behavior but also the ability to control one’s choices.

Furthermore, evidence from the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study suggests that stressors/adverse childhood experiences are both highly prevalent and associated with adult comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, chronic liver disease, depression, mental illness, obesity, smoking, and alcohol and drug abuse.25

These examples underscore that poverty/adverse childhood experiences perniciously stymie a child’s capacity to achieve his maximal potential and has implications for adult health. Termed “double jeopardy” by some, poverty presents both a multitude of risks undermining optimal health development and a dearth of resources to mitigate them.26

PROTECTIVE FACTORS FOR CHILD HEALTH DEVELOPMENT

Some people are able to develop mechanisms to deal successfully with the risks they face, thus enhancing their health and well-being. This quality, referred to as resilience, is critical for attaining optimal functional capacity, especially in the face of adversity.27,28,29 Factors contributing to resilience are often termed protective or promoting factors, and they may either be intrinsic to the individual (e.g., their temperament or disposition) or external (e.g., educational opportunities, a supportive family, social connectedness/support). Protective qualities can be found in the individual, the family, and the community, as well as through the relationships that emerge through interactions between these groups. Like risk factors (remember the example of poverty), protective and promoting factors often occur together. Health promoting and protective factors can be particularly important in mitigating the impact of stressful life events in vulnerable children, and some protective factors are more important than others for children at particular developmental stages29 (Table 20-1). Supportive grandparents, siblings, teachers, and mentors can all play a role in buffering children from the effects of risk factors associated with poverty. However, poverty and its related stressors can erode a parent’s ability to provide high-quality parenting.30 Therefore, bolstering interpersonal relationships and high-quality parenting is one way that clinicians can promote health.31

| Protective Factors | Developmental Period |

|---|---|

| Individual | |

| Low distress/low emotionality | Infancy–adulthood |

| Active, alert, high vigor, drive | Infancy–adulthood |

| Sociability | Infancy–adulthood |

| “Easy” engaging temperament | Infancy–childhood |

| Advanced self-help skills | Early childhood |

| Average–above average intelligence | Childhood–adulthood |

| Ability to distance oneself, impulse control | Childhood–adulthood |

| Internal locus of control | Childhood–adolescence |

| Strong achievement motivation | Childhood–adolescence |

| Special talents, hobbies | Childhood–adolescence |

| Positive self-concept | Childhood–adolescence |

| Planning, foresight | Adolescence–adulthood |

| Strong religious orientation, faith | Childhood–adulthood |

| Family/community | |

| Small family size (<4 children) | Infancy |

| Mother’s education | Infancy–adulthood |

| Maternal competence | Infancy–adolescence |

| Close bond with primary caregiver | Infancy–adolescence |

| Supportive grandparents | Infancy–adolescence |

| Supportive siblings | Childhood–adulthood |

| For girls: emphasis on autonomy with emotional support from primary caregiver | Childhood–adolescence |

| For boys: structure and rules in household | Childhood–adolescence |

| For both boys and girls: assigned chores: “required helpfulness” | Childhood–adolescence |

| Close, competent peer friends who are confidants | Childhood–adolescence |

| Supportive teachers | Preschool–adulthood |

| Successful school experiences | Preschool–adulthood |

| Mentors (elders, peers) | Childhood–adulthood |

Resilience in children can manifest in different ways and is dependent upon the child’s ability to develop specific noncognitive skills, capabilities, and capacities. Older children and adolescents who embrace challenges persist in addressing difficult tasks in the face of challenges, learn from criticism and see effort as the path to mastery, develop a mindset with the capacity to succeed in spite of difficult circumstances.32 Developing such skills, however, requires a sound emotional foundation in early childhood, the ability to communicate responsively with peers and adults, and the development of other capacities including executive function.33

HEALTH PROMOTION AND THE LIFE COURSE HEALTH DEVELOPMENT MODEL

Trajectory 1: Projecting forward several years, Xavier has significant language delays when he goes to school. In first grade, his teachers become concerned, but it is not until third grade that he is tested and found to have language and cognitive delays. His family is disrupted when his father needs to return to Mexico; his mother works two jobs just to make ends meet. His life is now affected by food insecurity, less parental attention, more screen time, and frequent housing moves. With poor grades and little support, he eventually drops out of school.

Trajectory 2: Xavier receives a comprehensive language assessment at age 2 and is placed in language and cognitive stimulation programs. His mother is supported through her local community center where they offer parenting classes and she learns parenting skills that foster her attachment with Xavier and promote his ability to self-regulate. Xavier attends a high-quality family-based child care center where he learns more socialization skills and has regular physical activity and planned healthy meals and snacks daily. He enters school with near-normal language function, normal body mass index, and cognitive and social development. He does well in school, particularly math and science. Although his father has to return to Mexico for a short time, his family receives additional assistance to maintain stable housing, food security, and consistent and supportive relationships with friends and teachers at school.

Health promotion integrates broad definitions of health and development into health care to enable “individuals to increase control over and improve their health. It involves the population as a whole in the context of their everyday lives, rather than focusing on people at risk for specific diseases and is directed toward action on the determinants or causes of health.”34

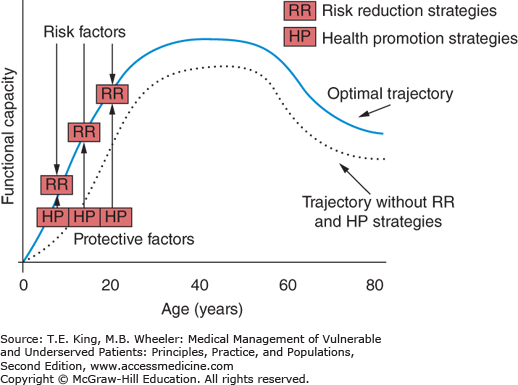

The Life Course Health Development (LCHD) model integrates the ideas that health develops over an individual’s lifetime and is influenced by environmental, physiologic, behavioral, and psychological factors into an analytic framework useful for health providers for health promotion.2,35 Positive or protective factors—genetic, environmental, or social—act to allow an individual to attain optimal healthy functioning. Negative influences on health, on the other hand, deter a person from achieving this potential. The balance of these forces determines the health trajectory of an individual (Figure 20-1).

Figure 20-1.

The health development trajectory: How risk reduction and health promotion strategies influence health development. This figure illustrates how risk reduction strategies can mitigate the influence of risk factors on the developmental trajectory, and how health promotion strategies can simultaneously support and optimize the developmental trajectory. In the absence of effective risk reduction and health promotion, the developmental trajectory will be suboptimal.2

Health professionals can have a significant impact on their patients’ health by helping parents take steps to decouple the impact of adversity on their child’s health development, providing services that can buffer the effects of different risks and by organizing interventions that provide the supportive scaffolding that promote optimal health development. The LCHD model frames health broadly and includes an ecological orientation that integrates the “upstream” social, environmental, and behavioral factors, influencing health in a way most often ignored by traditional medical models. Adoption of this framework requires a shift in clinical practice from major focus on the search for disease and disability to a perspective that also focuses on developmental assets and other factors that can be marshaled to enhance prevention and the active promotion of health.

Consistent with the life course orientation of Healthy People 202036 and a growing focus on the social determinants of health, the LCHD framework places special emphasis on the integration of the social determinants of health or non-biomedical factors (housing, income, access to healthy food, educational opportunity), thus acknowledging the special role that they play, especially during sensitive periods of development, on a range of significant health outcomes.

Viewed from the perspectives of LCHD, childhood represents an opportunity for health-care providers to intervene effectively to prevent disability and promote lifelong health during a developmental period in which interventions can be leveraged to improve the immediate health of children as well as the long-term health of the population as a whole. The integration of individual and population health promotion and disease prevention requires ongoing surveillance of the child and family functioning in order to identify strategic opportunities to support resilience and minimize risk. Finally, LCHD and the idea of health promotion provide powerful tools for tackling the vexing health problems of underserved children (Box 20-1).

THE VULNERABILITY OF CHILDREN

Children are uniquely vulnerable because they are rapidly developing and, as nonautonomous individuals, they are dependent on others for their health, safety, and well-being. Their vulnerability is dynamic because they are changing and these changes are exquisitely sensitive to external pressures. Thus, anticipating sensitive developmental periods in which children may be more vulnerable based on both their developmental capacities and their contextual environment as defined by their family, school, and community is crucial.19 Although all children are vulnerable, for some children this vulnerability is exaggerated by poor health, social or family circumstances, or other environmental threats, such as poverty and toxic stress.

Box 20-1. Linking Children’s Health Definition to the Life Course Health Development Framework and Changes in Clinical Practice

Transformation of the Concept of Children’s Health

Moves away from disease-based model

Focuses on:

Optimizing development and function

Maximizing individual and population potential

Highlights:

Interaction of environment, contextual factors, and the individual

Application of Life Course Health Development Framework

LCDH concept:

Individual-, family-, and community-level risk and protective factors interact to influence the health development of individuals over their lifetime

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree