Chapter 11 Understanding learning

Learning is not just about acquiring facts or knowledge. Social skills, beliefs and values are also learned. We learn how to respond emotionally, how to recognize symptoms and, as children, we learn appropriate (and inappropriate) ways of behaving (Fig. 1). If we understand how behaviour is learned we may be able to change it. We may wish to change to a healthier lifestyle, to learn how to monitor our own glucose levels or to overcome a phobia. Understanding learning has been of central concern to psychologists, and the source of much debate (Eysenck, 1996).

Theoretical background

Operant conditioning

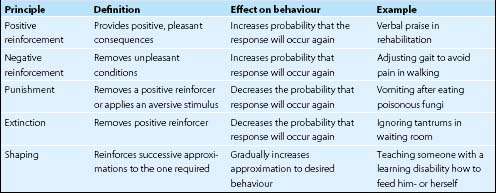

A kind of learning, known as operant conditioning, was described by an American psychologist, B.F. Skinner. In operant conditioning, the likelihood of a response occurring again is increased if the behaviour is followed by reinforcement. Thus, the behaviour is controlled by its consequences. The principles of operant conditioning have been established through experimentation on animals such as rats and pigeons, as well as humans (Table 1).