Chapter 29 Unemployment and health

As we move into the era of what has been called ‘liquid’ capitalism, we are witnessing increased part-time employment, more flexible work patterns and more self-employment. At the same time unemployment over the life course will become a more common experience for a sizeable section of the population. Unemployment will be especially high for young men (Luck et al., 2000). There will be more chronic unemployment and more workless households. Medical professionals will increasingly be faced with having to deal with the health effects of unemployment (Wadsworth et al., 1999).

The evidence and mechanisms

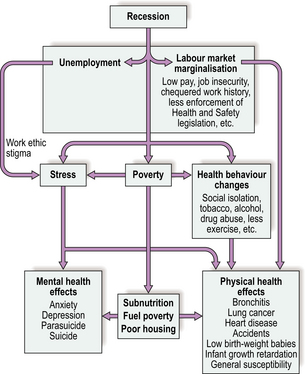

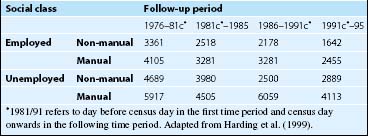

It is now accepted that unemployment is a stressful life event that can cause ill health and even mortality (Table 1). Research has also been able to capitalize on the volume of work carried out since the 1990s which gives more attention to the mechanisms that cause ill health. One way to summarize the research evidence is by considering causality and the possible links between unemployment and ill health and mortality (Fig. 1). We can consider each pathway in turn.

Table 1 Trends in death rates/100 000 persons by employment status and social class among men aged 36–64, 1971 cohort, England and Wales

The stress pathway – psychological morbidity and mortality

People who were committed to their work and who became redundant were found to be particularly disadvantaged.

People who were committed to their work and who became redundant were found to be particularly disadvantaged. Age and length of unemployment were likely to be intercorrelated, and so older people were less likely to become re-employed and were more likely to be sick. The middle-aged unemployed, in fact, were found to have the lowest well-being scores.

Age and length of unemployment were likely to be intercorrelated, and so older people were less likely to become re-employed and were more likely to be sick. The middle-aged unemployed, in fact, were found to have the lowest well-being scores.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree