18 | Unilateral and Bilateral Facet Dislocations |

| Case Presentation 1: Unilateral Facet Dislocation |

History and Physical Examination

A 34-year-old woman presented with neck pain after a head-on collision. She had no other associated injuries but presented to the emergency department in a cervical collar. Physical examination demonstrated that she was neurologically intact to motor, sensory, and reflex examination. Perianal sensation and rectal tone were normal. She was awake, alert, and cooperative with the examination but appeared to be holding her head slightly rotated toward the right side.

Radiological Findings

A lateral cervical radiograph revealed ~20% anterior translation of C5 on C6. Examination of the facet joints revealed one intact joint but that the other joint had a so-called bow-tie appearance (Fig. 18–1). Computed tomography (CT) showed that the left inferior articular process of C5 was perched on top of the left superior articular process; thus nonarticular surfaces were apposed. The right facet joint was normal, and magnetic resonance image (MRI) showed no herniated disk fragments in the canal.

Diagnosis

Unilateral left facet dislocation without a neurological deficit

| Case Presentation 2: Bilateral Facet Dislocation |

History and Physical Examination

A 19-year-old man presented to the emergency department following a high-speed motor vehicle accident. He reported neck pain and the inability to move his upper or lower extremities. He was a large, obese man with a barrel chest and broad shoulders. He exhibited pain with posterior cervical spinous process palpation. Neurological examination demonstrated that he could shrug and abduct his shoulders bilaterally; however, he could not flex his elbow and had no appreciable movement of his fingers or wrists. He had absent rectal tone, no perianal sensation, and no motor or sensory function in his lower extremities. He had already been started on a 48-hour methylprednisolone protocol. No other injuries were present.

Radiological Findings

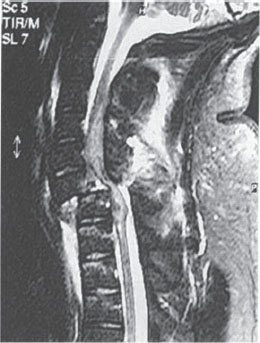

An initial lateral cervical radiograph demonstrated no visible injury; however, C5 was the lowest vertebra visualized. Subsequently, a swimmer’s view suggested a dislocation, but the level was difficult to discern (Fig. 18–2). A CT scan was quickly obtained, demonstrating nearly 100% anterior translation of C6 on C7 (Fig. 18–3) with dislocated facet joints bilaterally. MRI showed 100% canal compromise from translation. Though no herniated disk was noted posterior to C6, a bright signal was appreciated, likely representing edematous fluid (Fig. 18–4). Most importantly, intrinsic cord signal was noted that extended proximal to the dislocated segment.

Figure 18–1 Case 1: Preoperative lateral radiograph demonstrating the so-called bow-tie sign of the unilateral unapposed articular surfaces of C5 on C6.

Figure 18–2 Case 2: A swimmer’s view suggested a translational deformity, but the level was difficult to determine.

Diagnosis

Bilateral C6-7 facet dislocations with a C5 level complete spinal cord injury (American Spinal Injury Association-A) [ASIA]

| Background |

Understanding the Management Options

The optimal treatment of unilateral or bilateral facet dislocations is not clear. The role of nonoperative treatment is limited. If elected, it should be reserved for unilateral injuries in patients without neurological deficit or for those medically unfit for surgery. In such cases, external cervical orthoses are usually inadequate and a halo device should be applied. The inability of halo fixation to maintain reduction of bilateral facet dislocations has been previously well demonstrated.1

In most cases, some form of surgical stabilization is performed. Various surgical approaches can be used. If a successful closed reduction can be achieved prior to operation, either anterior or posterior surgery can be performed, with no clear evidence of the superiority of one approach over another. Conceptually, posterior instrumentation and fusion more directly addresses the posterior ligamentous complex or facet capsule disruption, which is the primary destabilizing lesion. However, in planning posterior surgery, postreduction preoperative MRI is performed to ensure that there are no fragments of herniated disk in the canal. Left undetected, further disk retropulsion and potentially a new neurological deficit can result from compression of the posterior construct. As an alternative, many surgeons routinely perform an anterior diskectomy, fusion, and stabilization following successful closed reduction of a facet dislocation. With this practice, postreduction preoperative MRI might be avoided, though the study may still be useful in finding fragments that have cranially or caudally migrated behind the vertebral body.

Figure 18–3 Case 2: Sagittal computed tomographic reconstruction showing the nearly 100% translational deformity of C6 on C7.

Figure 18–4 Case 2: T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating spinal cord compression and intrinsic spinal cord signal proximal to the dislocation.

Combined anterior and posterior surgery may also be performed. This is usually reserved for patients with more severe or missed injuries with fixed deformities. It is the authors’ preference to perform anterior surgery followed by posterior stabilization for patients with some highly unstable bilateral facet dislocations. If the facets are gapped or kyphosis remains after anterior surgery, posterior instrumentation is performed to avoid construct failure. Anterior/posterior surgery is rarely necessary for unilateral dislocations.

| Outcomes |

It is important to review the published clinical outcomes of treatment of facet dislocations. Feldborg Nielson et al12 found anterior fusion resulted in better pain relief than posterior wiring without fusion for facet dislocations. The authors thought this was from persistent residual motion in the unfused cases. In 22 patients with bilateral facet fracture-dislocations, Razack et al7 performed single-level anterior fusions with titanium locking plates. At an average follow-up of 32 months, only one case of construct failure was documented, though all patients eventually had solid fusions and achieved stability. Concerning reduction of facet dislocations, Vital et al7 found that 43% of 91 bilateral injuries could be successfully reduced using traction alone, 30% with manipulation under general anesthesia, 27% required anterior surgical maneuvers. Anterior diskectomy and plating was performed as the definitive treatment in all patients. Notably, there were several patients who had new-onset neurological deficits after reduction.

In a series of 24 patients with unilateral facet dislocations, Shapiro5 treated all with posterior interspinous wiring. Importantly, in two patients who had initially undergone a successful closed reduction, treatment with a halo alone led to recurrent dislocations; they thus eventually underwent posterior surgery. Fusion was achieved in 23 (96%) cases. Comparable clinical results were reported with interspinous wiring combined with lateral mass plating compared with facet wiring with iliac crest graft for unilateral facet dislocations. Greater maintenance of kyphotic correction was observed in the plate group compared with the facet wire/iliac crest graft group. In their reviews, Beyer and Cabenela9 found that unilateral facet dislocations or fracture-dislocations were better treated with operative intervention because nonoperative management led to a higher rate of late pain and instability.

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging before Reduction |

Rooted in Eismont et al’s case series,8 there exists a real potential for neurological decline with closed reduction, by either open or closed methods.8,9 It is generally believed that disk herniations, pushed back into the spinal cord by the cranial vertebra during reduction, are the cause. With this, many advocate prereduction MRI to rule out a disk herniation.8 This recommendation is poised, however, on the likely decision to perform an anterior procedure to remove the herniated disk prior to reduction.

In the unexaminable patient with an unknown or unmonitorable neurological status, prereduction MRI is prudent. In the awake, alert, and examinable patient, however, prereduction MRI may not be necessary. Two recent clinical reports have demonstrated that closed reduction of facet dislocation can be performed safely, provided that serial neurological examination can be performed.10,11 In one study,11 five of nine patients with facet dislocations had a new herniated disk on postreduction MRI that was not present on prereduction MRI. All underwent a successful closed reduction without neurological decline. Even though some patients had areas of increased signal within the spinal cord after reduction, no associated neurological decline was noted. In another study, Grant et al10 retrospectively reviewed their results with early closed reduction in 121 patients with cervical spine dislocations. Of the 80 patients who underwent postreduction MRI, 22% demonstrated a frank disk herniation, though this did not affect the degree or progression of neurological deficit.

In the end, the relative advantages and disadvantages of early reduction and anatomical alignment versus the increased complexity of performing anterior decompression and reduction on a dislocated spine are still not clearly established and will likely remain controversial in the near future.

| Authors’ Preferred Method of Surgical Management for Unilateral Dislocation (Case 1) |

In the case presented, it was the authors’ preference to perform an awake closed reduction followed by anterior diskectomy, fusion with iliac crest autograft, and instrumentation.

Pearls

Awake closed reduction was performed using Gardner-Wells traction. Sequentially increasing amounts of weight were applied, starting from 10 lb. An initial lateral was obtained with 10 lb of weight to insure that the occipitocervical junction or other region was not grossly distracting. After 20,30, and 40 Ib had been applied, there was ~20% of remaining overlap of the dislocated articular processes, As the patient was awake and readily examinable (and remained neurologically intact). a closed reduction manipulation was performed. Keeping the 40 Ib weight in place, a downward axial force was placed on the nondislocated side while simultaneously imparting an upward distracting force to the dislocated side. With this held, the head was then rotated toward the dislocated (left) joint. A palpable “clunk” was felt, suggesting reduction. The patient remained neurologically intact and a lateral film confirmed reduction of the facet joint. The weight was then reduced to 15 lb, the neck placed in slight extension, and another lateral radiograph obtained.

An anterior diskectomy, fusion, and instrumentation was planned. The author prefers the anterior method compared with the posterior method for several reasons. First, the patient can be easily maintained in continuous traction with the neck in extension while positioning on the operating table, With posterior surgery, even careful logrolling maneuvers into the prone position can cause movement and displacement of the cervical spine. Second, a postreduction MRI can be obviated because the disk will obligatorily be removed during the anterior procedure.

With baseline spinal cord monitoring signals established, a left-sided anterior cervical approach was performed. A bayoneted spinal needle was placed into a disk space as a marker. A lateral intraoperative radiograph was obtained to confirm the surgical level as well as maintenance of reduction. The disk was then marked and the needle was removed. The lower and upper portions of the cranial and caudal vertebral bodies were then subperiosteally exposed. The longus colli was reflected laterally and an adjustable self-retaining retractor was inserted. A knife was used to incise the anterior annulus. which revealed the typical grossly disrupted disk. All disk material was removed until the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) was visualized.

If the PLL is disrupted, the anterior thecal sac of the spinal cord should be visualized in its entirety. To confirm complete diskectomy, the thecal sac should not be indented in any region. If there does appear to be an indentation, an angled curette can be used to reach behind the vertebral bodies to retrieve disk fragments. If this yields no further fragments but suspicion is still high, sequential portions of the vertebral body can be removed using the burr to enable better cranial or caudal access to the canal. At feast half of the vertebral body should be maintained if stabilization is to be localized to the one motion segment. If additional bone is to be removed, it is more prudent to perform a full corpectomy.

Figure 18–5 Case 1: Postoperative lateral radiographs following anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion with structural autograft and plate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree