Chapter 37 Upper Cervical and Craniocervical Decompression

Pathology Overview

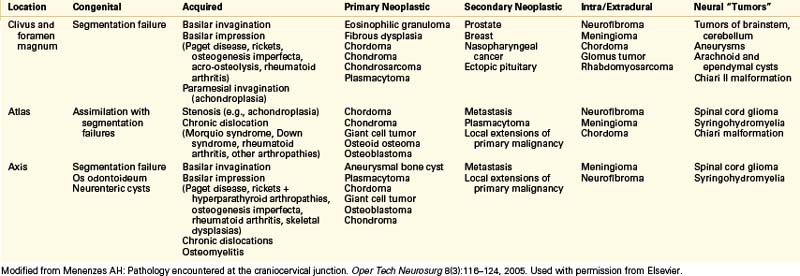

The pathologies possible at the craniocervical junction are varied.1 Most lesions requiring surgery are approached dorsally through a posterior fossa craniectomy and C1 laminectomy. Table 37-1 lists the pathologies encountered by category. In a more basic organization, the abnormalities can be divided into congenital abnormalities and developmental/acquired pathologies. In Box 37-1 the material is reorganized in an empirical fashion.

BOX 37-1 Origin of Pathology at Craniocervical Junction

Developmental/Acquired

Modified from Menenzes AH: Pathology encountered at the craniocervical junction. Oper Tech Neurosurg 8:116–124, 2005. Used with permission from Elsevier.

Ventral Approaches

Several routes to the ventral clivus and upper cervical spine are accepted. Standard approaches to the ventral cervical spine are limited by the mandible and oropharynx.2–4 Transoral routes to the lower clivus and upper cervical spine are acceptable and safe for addressing pathologies that cause craniocervical instability and that compress neurovascular structures. In 1917 Kanavel5 described the first transoral procedure, which he performed to remove a bullet lodged between the clivus and ventral atlas. In 1962 Fang and Ong6 reported the first series of six patients who underwent transoral decompression for atlantoaxial instability or congenital anomalies. Their high complication rate contributed to the slow acceptance of this approach.

A resurgent interest in the transoral approach led to the development of better techniques and instrumentation.7 Current techniques and practices have lowered complication rates considerably.8 Modern antibiotics and instruments have revolutionized and revitalized this operation. An extrapharyngeal approach for exposing the high cervical region is technically difficult but a reasonable alternative when the transoral approach cannot be used.9 The transoral approach remains an excellent tool in the surgeon’s armamentarium for ventral decompression. It is also versatile in that the upper clivus rostrally and C3 vertebral body caudally can be accessed. The authors prefer this route for extradural pathology. Dural closure is difficult in the transoral setting, and a lateral approach is preferable for intradural lesions. The far-lateral approach is quite robust for this purpose.

As minimally invasive surgery becomes more prevalent and patient demand for it increases, approaches to the upper cervical spine and clivus have become the target of efforts to minimize incisions and complications. In 2008 an endoscopic endonasal approach to odontoid resection was reported.10

Surgical Technique

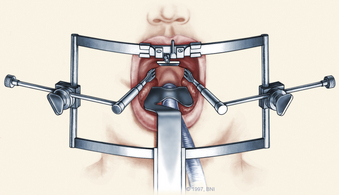

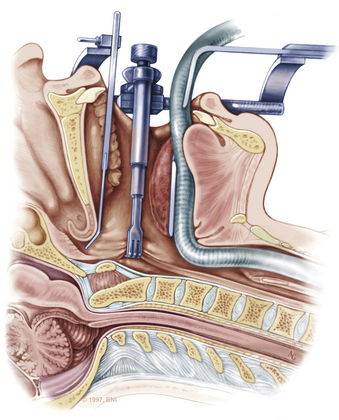

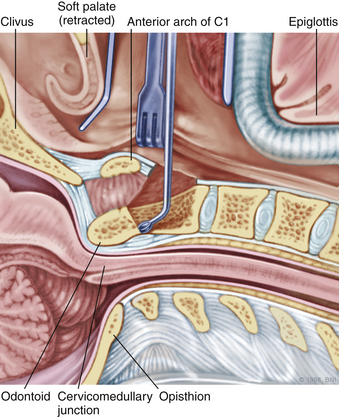

The patient is placed in the supine position on a standard operating room table with the head fixated in a Mayfield three-pin head holder (Codman, Inc., Randolph, Mass.) or a halo-ring adapter. A Spetzler-Sonntag transoral retractor (Aesculap, San Francisco) is positioned over the mouth. Retractors are used to form a rectangle of exposure. The palate is elevated cephalad, and the tongue and endotracheal tube are retracted caudally. The tonsils and lateral oropharyngeal walls are covered with moist gauze and retracted outward (Figs. 37-1 and 37-2). Transnasal catheters and palatal retraction sutures can be used in lieu of the Spetzler-Sonntag retractor. If the mouth cannot be opened sufficiently, a mandible-splitting approach can be used11 and a tracheostomy performed before the surgical approach begins.

After the retractor is placed in its final position, the oral cavity is cleansed with povidone-iodine (Betadine). A preoperative dose of antibiotics that includes coverage for oral flora should be administered. The authors prefer cefepime and metronidazole. The surgeon sits at the patient’s head, necessitating an adjustment in orientation for the duration of the case. An operating microscope is brought into the field. Stereotactic guidance may be used to guide the angle of approach and to confirm the location before the palatal incision is made.12 Alternatively, fluoroscopy can be used for confirmation. Electrocauterization is used, and the incision proceeds down to bone. Subperiosteal dissection is used to expose the lower clivus, atlas, and axis. The authors seldom find it necessary to divide the soft palate unless the upper clivus is the target. Self-retaining retractors are placed to maintain exposure.

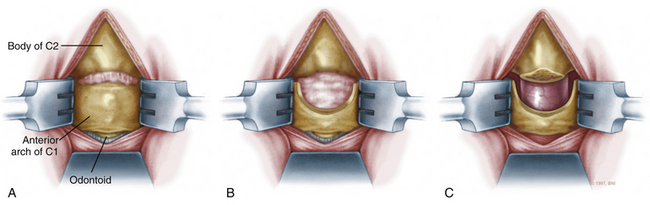

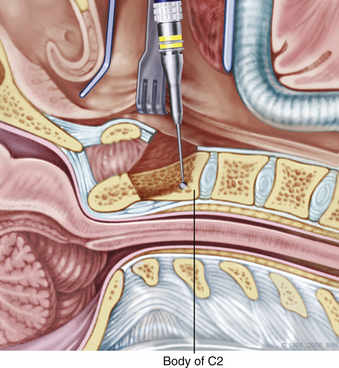

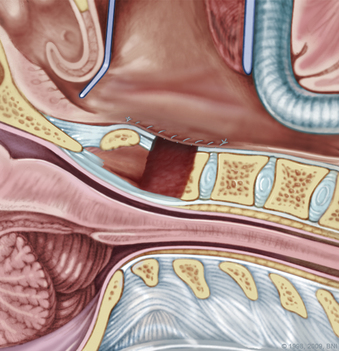

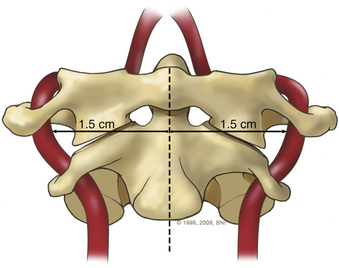

A high-speed air drill is used to remove the ventral arch of C1. The ventral arch of the atlas is the load-bearing portion of the bone.13 An effort should be made to preserve a portion of the arch to prevent spread of the lateral mass and to maintain orientation relative to midline. Approximately 70% of patients undergoing ventral decompression require supplemental internal fixation. This number increases to 90% in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.14 The remaining anterior tubercle of C1 is left as a landmark for posterior screw fixation (Fig. 37-3A–C). Stereotactic navigation may be useful in cases requiring hardware fixation, especially if a large ventral portion of C1 and surrounding bone must be removed. Various instruments can be used to remove bone and tissue carefully. Long-handled curettes and rongeurs, as well as bipolar cautery, are useful adjuncts (Figs. 37-4 to 37-6). The average distance between the vertebral arteries is approximately 3 cm. The anatomic “safe zone” is 1.5 cm lateral to midline in both directions (Fig. 37-7). Preoperative radiographs must be evaluated carefully. In many cases, CT angiography can delineate aberrant or asymmetrical vasculature. Further lateral dissection places the hypoglossal nerve, vertebral artery, and cervical neurovascular bundle at risk.15

During a transoral odontoidectomy, cautious dissection and a methodical approach are essential to minimize the risk of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistula. The superior ligamentous complex (consisting of the apical and paired alar ligaments) must be sectioned to remove the dens. This step should be performed first with curved curettes. This region is often adherent to the dura, and great care must be taken to avoid durotomy.16,17 A thin shell of bone can be left to avoid a dural tear. Once the last of the odontoid is removed, the frameless guidance or a lateral radiograph can be checked with a radiopaque instrument in the field.18

Pitfalls and Complication Avoidance

Preoperatively, many patients requiring ventral decompression may be severely debilitated. Postoperatively, they may need a course of parenteral nutrition, long-term rehabilitation or skilled-nursing care placement, and a long convalescent period. The surgeon should make it a priority to ensure that patients and their loved ones have appropriate and realistic expectations about outcomes and that they understand the possible risks and complications associated with the procedure.

Lateral Approaches

The lateral craniocervical region is rarely involved with bony compressive lesions. Most of these lesions are strongly associated with assimilation of the atlas into the occiput when segmentation fails between the last (fourth) occipital and first cervical sclerotomes. The sclerotomes fail to separate and remain fused, resulting in an incompletely separated atlas and sometimes a bifid lamina. This defect is associated with various syndromes (e.g., achondroplasia, Morquio syndrome) and usually occurs in conjunction with other occipitocervical bony anomalies. Astute clinicians should be wary of such entities, which may be common, such as Chiari I malformations and Klippel-Feil syndrome. Rarer but no less significant entities such as basilar invagination and congenital fusion of C2 and C3 also occur.19,20 Thus lateral approaches may need to be part of a larger operative plan and used in conjunction with other techniques to completely address the pathologies present.

Lateral compression can be unilateral or bilateral. Stenosis of the foramen magnum leads to pain (usually occipital or high cervical) and possibly myelopathy. Instability may be present, and a fusion procedure may be necessary in addition to decompression. Other lesions located ventrally in the foramen magnum such as vertebrobasilar aneurysms and meningiomas can be approached laterally. A lateral approach allows adequate exposure while protecting delicate neural structures.

Lateral approaches to the upper cervical spine have been in development for decades. These surgeries eventually resulted in the techniques commonly used today. Henry described a technique for gaining access to the V2 and V3 segments of the vertebral artery through a similar incision.21 Whitesides and Kelly further developed lateral approaches for spinal fusion using a similar incision.22 Their technique was based on dividing the sternocleidomastoid muscle at its origin in the mastoid and reflecting it dorsally. Since then, numerous authors have modified, refined, and expanded this approach to the lateral upper cervical spine and foramen magnum for both extradural and intradural lesions.23–26 Some authors have reported more aggressive approaches involving mobilization of the vertebral artery and sectioning of the sigmoid sinus when exposure needs to be increased.27 Approaches have been modified to allow resection of lesions traversing the foramen magnum and into the upper cervical spine—the so-called “extreme lateral” approaches.28 Either a laterally or medially based incision can be used with the muscle flap directed medially or laterally, respectively. The authors’ preferred method is based on a dorsal midline approach.

Surgical Technique for Far-Lateral Approach

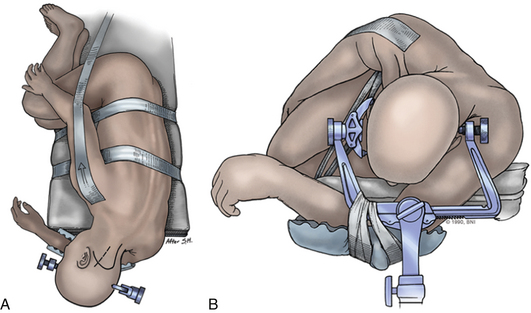

Intraoperative stereotactic navigation can be helpful with the far-lateral approach. During resection of tumors it can be useful to monitor the lower cranial nerves in addition to SSEPs. The patient is placed in the three-pin head holder with one pin on the forehead in the supraorbital area of the ipsilateral forehead. The two-pin portion is placed low on the contralateral occipital bone, above the level of the inion, leaving the retroauricular area to the midline open (Fig. 37-8A).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree