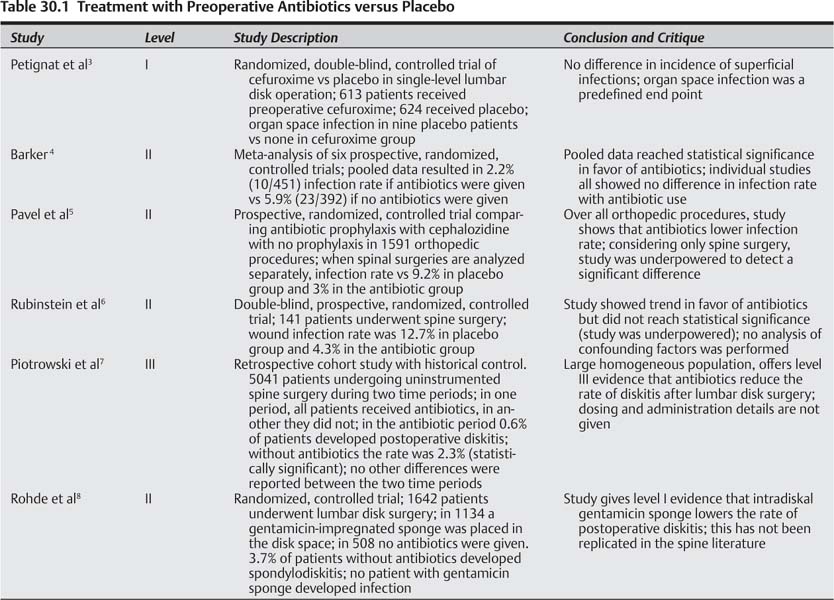

30 Surgical site infections complicate ~1.1% of surgical procedures performed in the United States annually.1 Several factors have been identified that may contribute to a higher perioperative risk of surgical site infection, including patient age, nutritional status, smoking status, comorbid conditions like diabetes and obesity, coexisting infection, immunodeficiency, and length of pre- and postoperative hospital stay. Administration of perioperative antimicrobial agents has been widely adopted as a standard of care for many surgical procedures. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) outlines four principles for maximizing benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis: (1) use an antimicrobial agent for all operations in which it has been shown to reduce infection rates based on evidence from clinical trials or those cases in which an infection would prove catastrophic; (2) use an agent that is safe, inexpensive, and likely to cover the spectrum of organisms for a given operation; (3) time the dosing of the agent so a maximal serum concentration occurs at the time of skin incision; and (4) maintain therapeutic levels of antibiotic agent until the wound is closed.1 This chapter reviews the existing literature on the use of antibiotic prophylaxis as it pertains to spinal surgery. We shall begin by addressing the first of the foregoing points from the CDC, reviewing evidence from clinical trials regarding the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in spinal surgery. We will give an overview of the subgroups of patients undergoing spinal surgery who may be at higher risk for infection. Finally, we shall address the choice of antimicrobial agent, and the schedule for dosing, including redosing of antibiotic during an operative procedure. To achieve these ends, we have performed a review of the literature to determine the best evidence for each of these questions. A Medline search used the terms “spine AND antibiotic prophylaxis AND infection” to identify studies published in 2006 or later. The North American Spine Society (NASS) guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in spine surgery were reviewed in detail, including a review of studies cited in this publication.2 These guidelines represent a systematic review of all publications available on this topic as of December 2006. Identified were two level I studies, six level II studies, and 13 level III studies. There is one level I study directly comparing a second-generation cephalosporin, cefuroxime, with placebo in a prospective, randomized, double-blinded fashion. Petignat et al3 performed a study in adult patients undergoing surgery for herniated lumbar disk. Six hundred thirteen patients received cefuroxime in a single, preoperative dose, whereas 624 patients received placebo in the same fashion. All parties were blinded to the medication administered until completion of data analysis. The predetermined end points were surgical site infection as defined by the CDC: superficial wound infection (above the fascial layer), deep wound infection (below the fascia), and organ space infection (infection of the disk, vertebra, or paravertebral structure). Superficial and deep infection rates were identical, but in the placebo group there were nine organ space infections, compared with none in the cefuroxime group (p < 0.01). The calculated number needed to treat to prevent one infection was 69. Strengths of the study are its large size (prospectively designed to be adequately powered), its homogeneous population, the similarity of the control and experimental group, and its prospective and blinded analysis. Limitations of this study include a lack of information about how many patients were screened for eligibility, lack of intention-to-treat analysis, and the fact that the diagnosis of infection was largely dependent on the treating physician. The study had a very low crossover rate, thus minimizing the effect of intention-to-treat analysis. Furthermore, all examiners and study personnel remained blinded throughout the follow-up period, minimizing the bias possible from physician identification of infected cases. In addition, six of the nine cases with organ space infection were confirmed with culture from the infected area. This study represents the first level I evidence that a single dose of antibiotic prophylaxis is effective in reducing the rate of infection after spine surgery. Barker performed a meta-analysis of six randomized, controlled trials on the effects of prophylactic antibiotics on infection in spine surgery.4 The aggregate data from these six trials represented 843 patients undergoing surgery. In all six trials, the infection rate for patients given a dose of perioperative antibiotics was lower than in those given placebo. However, in none of the trials was the result statistically significant. After pooling the data from the six trials, an infection rate of 2.2% was found in the antibiotic group versus 5.9% in the placebo group (p? 0.01). Because none of the individual trials reached significance, this meta-analysis represents level II data that antibiotics lower infection rate in spinal surgery. Pavel et al5 performed a prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 1591 clean orthopedic surgery procedures assessing the infection rate with and without perioperative antibiotics. Results showed a statistically significant reduction in infections over the entire study group. Subgroup analysis of patients undergoing spine surgery showed infection rates of 9.2% in the placebo group and 3.0% in the antibiotic group. The difference in infection rate was not statistically significant, but the number of patients in the spine surgery group was too small to detect such a difference. Thus this study shows a trend toward lower infection rate with prophylactic antibiotics and represents level II evidence favoring the use of antibiotic prophylaxis. Rubinstein et al6 present data from 141 patients undergoing “clean” operations on the lumbar spine. Of the 71 patients receiving placebo, nine (12.7%) developed an infection, whereas in the antibiotic group, three of 70 (4.3%) developed an infection. This result did not reach statistical significance, once again showing that the study was under-powered. Further limitations of this study include a lack of discussion of the coincident risk factors for infection in each group, such as the use of instrumentation. A large retrospective study performed by Piotrowski et al7 reviewed the infection rate in 5041 patients who underwent lumbar disk surgery during a time period when no antibiotics were used compared with those performed when antibiotics were used routinely. The rate of diskitis was 0.6% with antibiotics and 2.3% without. This retrospective study with historical controls represents level III evidence that antibiotic use decreases the rate of diskitis after lumbar disk surgery. A study performed by Rohde et al8 compared the rate of diskitis after lumbar disk surgery between one group of 1134 patients in whom a gentamicin-impregnated sponge was left in the disk space and another group of historical controls in which no antibiotics were used. Nineteen (3.7%) of the patients in whom no antibiotics were used developed spondylodiskitis versus none in the sponge group. These results have not been replicated in the spine literature, nor studied prospectively. Based on the evidence just reviewed, including one level I study, it is reasonable to conclude that perioperative antibiotic use lowers infection rate in spine surgery. Several prospective, randomized trials have showed a trend in favor of antibiotic use, but have been underpowered to show a significant advantage. Table 30.1 summarizes studies on this topic. Putative disadvantages to antibiotic use include exposure of patients to possible adverse drug reactions, encouraging the emergence of resistant organisms, and increasing cost. However, the available evidence favors prophylactic antibiotic use in spine surgery. Pearl • Based on one level I study and several level II studies, evidence suggests that use of perioperative antibiotics in spine surgery decreases infection rates. There are no level I data published regarding this topic. Payne et al9 published a prospective, randomized study of patients undergoing single-level lumbar laminectomy without fusion. One hundred three patients had a wound drain placed before closure and removed on postoperative day 2. Ninety-three patients had no drain placed. Two patients in the drain group became infected versus one in the no-drain group. Thus no difference in the rate of infection was reported. It is concluded that placement of a wound drain does not increase or decrease the risk of infection. In criticism, given the low overall rate of infection, the study was significantly underpowered to show a difference, thus this represents level II data. In a single-institution, retrospective, case-control study, Kanafani et al10 identified 27 cases of infection in 997 spine surgery patients and compared them with randomly selected controls. Compared with controls, cases were older (mean age 59 vs 47 years), more likely to have diabetes (odds ratio 4.0), and more likely to have foreign body implantation (odds ratio 3.4). All patients were given some manner of prophylactic antibiotics, though the details of the regimen are not made clear. No suggestion is given as to alterations of the antibiotic regimen for patients with higher-risk comorbidities. Olsen et al conducted a similar retrospective case-control study, again identifying 41 patients with surgical site infection according to CDC definition.11 All patients had received at least one dose of perioperative antibiotics. The authors performed univariate analysis of several predetermined factors thought to increase infection risk. Of those that appeared significant, postoperative urinary incontinence, posterior approach for surgery, surgery for tumor, and morbid obesity remained as independent risk factors on multivariate analysis. This study provides level III evidence that obesity (body mass index > 35) is an independent risk factor for postoperative infection. A retrospective cohort study by Wimmer et al11 identified 22 patients with postoperative infections among a group of 850 spine surgery patients. Subgroup analysis confirmed that obesity was an independent risk factor for surgical site infection. Rechtine et al12studied 117 consecutive patients who underwent thoracic or lumbar instrumented fusion following spine trauma and identified 12 patients with infection. Among 61 patients who were neurologically intact there were three infections. There were two infections among 39 patients who had incomplete neurological injuries. This was not statistically different from intact patients. However, seven of 17 patients with complete spinal cord injury developed infection. Complete spinal cord injury was found to be an independent risk factor for infection. This study is limited by its retrospective design and cohort comparisons. It does represent level III evidence that complete spinal cord injury increases the risk of postoperative surgical site infection. Two retrospective case-control studies of pediatric patients undergoing spine fusion have attempted to identify risk factors for infection in this population. Milstone et al13 identified 39 cases of surgical site infection in 989 instrumented pediatric spine fusions. Infected patients were more likely to have an underlying medical condition, to have > 10 levels fused, or to have had a previous spine surgery. Labbe et al14 performed a similar study, reporting 14 infections after 270 spine surgeries. This group discovered an infection rate of 32% in patients with myelodysplasia in comparison with 3.4% in patients without myelodysplasia. These studies are level III evidence of factors that may increase infection risk in the pediatric population. Although no level I data exist, several level III studies provide some guidance as to the risk factors that predispose the spine surgery patient to surgical site infection. Patients who are obese most clearly seem to be at higher risk. Older patients, patients with diabetes mellitus, those who undergo operations with implanted foreign bodies, as well as those with postoperative urinary incontinence may be at higher risk as well. In the pediatric population, patients with complicated medical conditions like myelodysplasia as well as those undergoing longer fusions and those who have had previous surgery may be at higher risk. Finally, a single study has suggested that patients with complete neurological injury are at higher risk (Table 30.2). Pearls • Patients who are older, have diabetes, undergo operations that involve instrumentation, or have postoperative incontinence may be at higher risk for postoperative infection. • There are no data upon which to base conclusions about a specific antibiotic regimen for high-risk patients.

Use of Prophylactic Antibiotics in Spine Surgery

Is Antibiotic Prophylaxis Effective?

Is Antibiotic Prophylaxis Effective?

Level I Data

Level II Data

Other Studies

Summary

Factors Influencing Rate of Infection after Spine Surgery

Factors Influencing Rate of Infection after Spine Surgery

Level I Data

Level II Data

Level III Data

Summary

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree