CAUTION

CAUTIONWhen non-pharmacological approaches have been tried and yet symptoms persist, medication trials are then recommended. The choice of medication depends on the specific symptom targets, the severity of symptoms, and side-effect profiles. Because efficacy is usually only modest, it is important to discuss with families realistic expectations for improvement and continue using non-pharmacological measures. Also keep in mind that the natural course of many symptoms is to resolve later during the dementia illness, so careful reductions in doses or even discontinuation of medications can be attempted after a period of stability.

TIPS AND TRICKS

TIPS AND TRICKSEducation about the disease, course, and prognosis.

Referral to a support group network or advocacy group (e.g. Alzheimer’s Association).

Assess need for additional help (e.g. other family members, paid caregivers, adult day health, respite programs).

Suggest changes to a patient’s environment.

Reduce overstimulation (e.g. turn off television, move bedroom to a quieter area).

Improve daytime lighting.

Add healthy activities.

Exercise.

Art or recreation therapy.

Social visits from family or volunteers.

Structured activities (e.g. senior center, adult day health).

Agitation and aggression

Agitation and aggression are terms used to describe a cluster of symptoms where patients are physically or verbally overactive in a way that is distressing to themselves or those around them. Symptoms can be in mild forms such as pressured pacing, difficulty sitting still, and irritability. They can also be severe, where examples include throwing objects and physically assaulting others. Agitation and aggression result in compromised access to care, hospitalizations, or admissions to long-term care settings. Therefore appropriate treatments are imperative for the quality of life and safety of both patients and caregivers. Pharmacological treatment options for agitation are summarized in Table 8.1, and include the cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine, antidepressants, atypical antipsychotics, adrenergic antagonists, and benzodiazepines. Specifics are discussed below.

Mild agitation

Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine

Non-pharmacological approaches are recommended for mild agitation, because mild agitation is more likely to respond to non-medication strategies, and because the side-effects of most drugs used to treat agitation outweigh the potential benefit. However, the primary agents used for cognition, cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, may be of some utility. Post hoc analyses have shown that Alzheimer’s disease patients taking cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine) and memantine have had less severe or fewer behavioral symptoms than patients taking placebo. However, it is important to realize that persons with moderate or severe behavior symptoms were excluded from these studies. The cholinesterase inhibitors are also indicated for vascular dementia, DLB, and PDD. As these medications already are recommended for their cognitive effects, it is worthwhile establishing adequate trials of these drugs if patients are also exhibiting mild agitation.

Table 8.1 Medication choices for dementia-related agitation

| Agitation characteristics | Medication choices | Time to response |

| Infrequent Minimal distress Redirectable | Cholinesterase inhibitors Memantine Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | Weeks |

| Frequent Significant distress Interferes with necessary care | Atypical antipsychotics Prazosin | Days to weeks |

| Physical aggression (hitting, kicking, throwing things) The safety of the patient or others is at risk | Atypical antipsychotics Benzodiazepines Anticonvulsants | Days |

Contraindications to cholinesterase inhibitors include severe liver or lung disease, bradycardia, and severe peptic ulcer disease. Prominent side-effects are nausea and diarrhea, which can be minimized by very slow upward titrations no more quickly than every 4–6 weeks. Memantine is an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist and is indicated for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. This medication is generally well tolerated with few side-effects. In some individuals, there may be a transient worsening in confusion.

Antidepressants

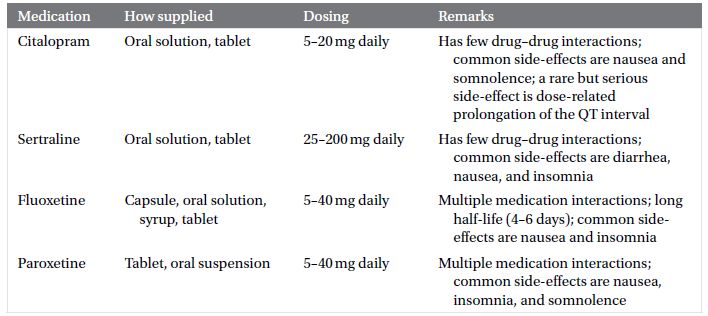

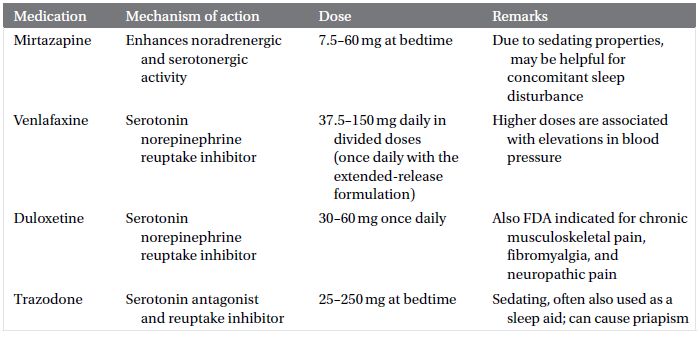

Antidepressant medications that have been studied for dementia-related agitation include the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and trazodone (Tables 8.2 and 8.3). Results are mixed, and therefore they are a potential option for treatment in individualized cases but not routinely recommended by treatment guidelines. They may be considered for patients with milder symptoms or those who do not tolerate or do not respond to antipsychotics.

Table 8.2 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Table 8.3 Other antidepressants

Moderate to severe agitation and aggression

Antipsychotics

For more severe degrees of agitation, in which distress or risk to the patient and caregivers requires immediate intervention, antipsychotics are the agents with demonstrated, albeit modest, efficacy. Because of a high adverse effect burden of the older (“typical,” e.g. haloperidol) antipsychotics, the second-generation (“atypical”) antipsychotics are preferred. The atypical antipsychotic medications that have been studied for dementia-related agitation include olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, and aripiprazole.

Unfortunately, the side-effects of the atypical antipsychotics are also significant and limit their use. These include sedation, falls, and extrapyramidal symptoms. These drugs can cause metabolic syndrome, but this problem is of less concern in the elderly dementia population than younger persons. Older adults are also particularly vulnerable to extrapyramidal symptoms, such as parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia.

A notable concern is an increased risk of death associated with antipsychotic drug use in dementia patients with agitation and psychosis, which is the basis for a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) black box warning against use of these agents. A 2005 analyses of 17 atypical antipsychotic placebo-controlled trials that enrolled 5377 elderly patients with dementia-related behavioral disorders found an approximately 1.6–1.7-fold increase in mortality rate (4.5%, compared with 2.6% in the patients taking placebo). In 2008 the FDA expanded the black box warning to first-generation antipsychotics as well, based on two large retrospective studies indicating that risk of mortality associated with first-generation antipsychotics was comparable to or exceeded that of the atypicals. Some data suggest that sedation is associated with this increased mortality.

Although there is a negative side-effect profile and increased risk associated with atypical antipsychotics, there is also significant risk to inadequate treatment of agitation. In many situations where a patient’s agitation and aggression are endangering themselves or others, the benefits of use often outweigh risks. Many patients and families also express a willingness to accept a small increased risk if the patient’s quality of life meaningfully improves with antipsychotic treatment. For these reasons atypical antipsychotics are still commonly used and included in treatment guidelines. Information specific to each atypical antipsychotic is summarized in Table 8.4.

CAUTION

CAUTIONStay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree