Vasculitides Involving the Central Nervous System

Key Points

Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) is a rare disorder, far less common than mimics such as reversible vasoconstriction syndrome or secondary CNS involvement by systemic vasculitis.

Cerebral angiography is of very limited sensitivity in the evaluation of PACNS, a disorder usually manifest in the distal arterioles beyond the limits of angiographic sensitivity.

The understanding, categorization, and treatment of vasculitides affecting the CNS have progressed substantially in the past two decades, and therefore clinical requests for cerebral angiography to “rule out vasculitis” are much more frequent. While it should seem intuitively obvious that a good-quality angiogram would be highly relevant to the diagnosis of CNS vasculitis, the question of the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of angiography in this group of patients warrants some elucidation.

Vasculitides are a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by inflammatory and necrotic changes in the blood vessel wall. When dealing with a neurologic patient, the first question to consider is whether the disorder in question is systemic or confined to the CNS.

Systemic Vasculitides

Rheumatologists tend to categorize systemic vasculitic disorders according to whether the vessel involvement is large (giant cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis), medium (polyarteritis nodosa, Kawasaki disease), or small. The small vessel vasculitides are separated into those positive for ANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies), including Churg–Strauss, and Wegener’s granulomatosis, and negative for ANCA (lupus Fig. 27-1, Sjogren’s syndrome, and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis) (1). A multitude of other conditions are associated with vasculitic changes and CNS involvement including arteriopathic complications of HIV infections, neurosyphilis, hepatitis C, herpes zoster complications, Lyme disease, (2), and so on. Even rarer entities will need to be considered in particular patients, for example, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) (3), or Eale’s syndrome (4). Susac syndrome (5,6) may need to be considered in ophthalmology patients, Köhlmeier–Degos syndrome (malignant atrophic papulosis) (7) in patients with spontaneous gastrointestinal infarctions or perforations with CNS involvement, or Behçet’s disease when there is basal ganglia or brainstem involvement (8,9). Angiocentric fungal infections, nocardia, or intravascular lymphoma (10) may all present with imaging features identical to those of CNS vasculitis.

Systemic vasculitis with secondary involvement of the CNS occurs with a prevalence of approximately 15/100,000 to 30/100,000, and while these diseases are rare, this prevalence far exceeds that of primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS). The role of angiography in the setting of a known systemic vasculitis will be determined by the particular circumstances in hand, and may include evaluation of the great vessels of the aortic arch, renal angiography, and evaluation of the extracranial carotid and vertebral arteries.

Primary Angiitis of the CNS (PACNS)

PACNS is a rare disorder with a peak presentation around the age of 50 years, more commonly seen in males (11), but sometimes seen even in children (12). Older papers dealing with CNS vasculitis include a substantial number of patients who would now be distinctly categorized under reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (see Chapter 26), and therefore a deal of confusion can arise in describing the entity of PACNS when this distinction is not clear. The symptoms and manifestations of PACNS likely relate in part to the size of vessel involvement. Proximal involvement close to the circle of Willis tends to give a picture of focal deficits, infarctions, transient ischemic attacks, and ataxia (Fig. 27-2). More distal small vessel involvement tends to cause vague, nonspecific complications such as personality and cognitive impairment. The distinction is relevant to the diagnostic angiographic evaluation of the patient, because there is a higher likelihood that with the latter pattern of small vessel involvement the angiogram will be normal (Fig. 27-3).

There may be different subtypes of PACNS, but the most classic presentation is that sometimes referred to as “granulomatous angiitis,” which is seen in more distal vessels, causing a multitude of infarctions of different sizes and ages,

diffuse dull headache, and abnormal CSF. MRI demonstrates ischemic lesions and sometimes leptomeningeal enhancement (10% to 15%) (13), which can serve as a target for biopsy. Cerebral angiography is normal in some series, most likely when the disease is exclusively confined to the small distal vessels (11), but other series of biopsy-proven granulomatous angiitis demonstrate consistently abnormal, although nonspecific, findings of vessel irregularity and beading (14). Other subsets of patients with primarily lymphocytic perivascular infiltrates or PACNS featuring histologic overlap with cerebral amyloid angiopathy are also described (15,16).

diffuse dull headache, and abnormal CSF. MRI demonstrates ischemic lesions and sometimes leptomeningeal enhancement (10% to 15%) (13), which can serve as a target for biopsy. Cerebral angiography is normal in some series, most likely when the disease is exclusively confined to the small distal vessels (11), but other series of biopsy-proven granulomatous angiitis demonstrate consistently abnormal, although nonspecific, findings of vessel irregularity and beading (14). Other subsets of patients with primarily lymphocytic perivascular infiltrates or PACNS featuring histologic overlap with cerebral amyloid angiopathy are also described (15,16).

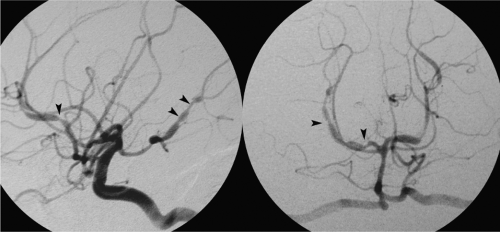

Figure 27-1. Angiographic appearance of intracranial vasculitis. A patient with fluctuating neurologic deficits in the course of treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus demonstrates a profusion of intracranial irregularities of the anterior and posterior circulation (arrowheads). The question is always asked, how do you tell the difference between this and intracranial atherosclerotic disease? There are several answers to this question, including the acknowledgment that at times one cannot tell. Atherosclerotic lesions are classically taught to be eccentric on the vessel, arteritis concentric. On the other hand, modern understanding of the genesis of atherosclerosis would suggest that the difference between inflammatory arteritis and atherosclerotic narrowing is specious, as they both represent overlapping pathophysiologic mechanisms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|