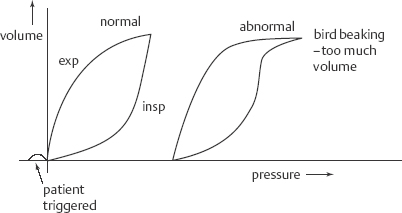

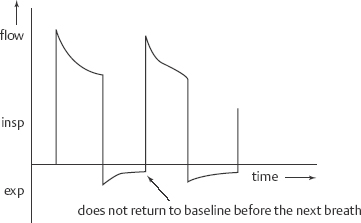

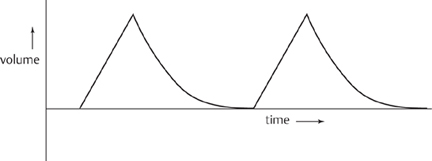

17 Ventilator Management Mariana Nunez, Roopa Kohli-Seth, Zinobia Khan, Moses Bachan, and Jennifer A. Frontera Mechanical ventilation (also known as respiratory failure) is common in critically ill patients. Neurologic patients often require mechanical ventilation for failure to protect the airway due to poor mental status or neuromuscular disease, rather than for pulmonary insufficiency. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) which is commonly used in COPD exacerbation, can be used in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Guillain-Barré, or myasthenia gravis patients when there is a minimal aspiration risk. Decreased mental status is a contraindication to NPPV. This chapter will focus on positive pressure ventilation in intubated patients. For details on intubation, see Chapter 16. Assess pulmonary and cardiac history (history of pneumonia, COPD, reactive airway disease, pulmonary emboli, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction (MI), smoking history), details of intubation (including if it was a difficult, complicated intubation), duration of mechanical ventilation, and modes used. Look for a recent history of secretions (noting their color and character), mucous plugging, or atelectasis. Assess vital signs, oxygenation, and end-tidal CO2; check ETT position (should be ~22 to 24 cm at the lips, depending on the patient’s size), assess for ETT air leak (listen at mouth for gurgling with inspiration), assess for signs of respiratory distress (tachypnea, diaphoresis, retraction, paradoxic abdominal breathing, cyanosis), and auscultate the lungs and heart. Assess for excessive secretions and sputum production. Indications for mechanical ventilation include The following suggest the need for mechanical ventilation: The pressure volume curves in Fig. 17.1 demonstrate both patient triggered breaths and if the patient is receiving too much tidal volume. Extrinsic PEEP is the PEEP set on the ventilator (typically beginning at 5 cm H2O). Intrinsic PEEP is also known as stacking or auto-PEEP and occurs when there is insufficient time for complete expiration of a tidal volume. On ventilator flow curves (see below), the expiratory phase fails to return to baseline when the inspiratory phase starts. An expiratory pause maneuver allows quantification of auto-PEEP (normal auto-PEEP should be zero). With auto-PEEP there is increase work of breathing because the patient must generate enough pressure to overcome this intrinsic PEEP and trigger the ventilator. The easiest way to treat auto-PEEP is to slow the RR and allow for additional expiratory time (this may require sedation). Other options include increasing flow rates to allow for a longer expiratory phase and applying extrinsic PEEP (<80% of auto-PEEP) to ease the work of breathing. Lower TV can limit the risk of hyperinflation as well. COPD patients are particularly susceptible to auto-PEEP. Excessive auto-PEEP, just like extrinsic PEEP, can lead to hypotension due to elevated intrathoracic pressures and decreased venous return (Fig. 17.2). Fig. 17.1 Tidal volume: Pressure volume curves demonstrating both patient triggered breaths and if patient is receiving too much tidal volume. Fig. 17.2 Intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP): On ventilator flow curves the expiratory phase fails to return to baseline when the inspiratory phase starts. In this mode, inspiration is terminated after a present TV is delivered a set number of times per minute. The pressure delivered depends on the lung mechanics (resistance and compliance). Advantages of this mode are that TV and minute ventilation are guaranteed, but disadvantages are that the airway pressure is not controlled, and this mode is somewhat less comfortable than other modes. Troubleshoot peak and plateau airway pressures. Examples of volume cycled ventilation include:

History and Examination

History

Physical Examination

Neurologic Examination

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Evaluation

Life-Threatening Diagnoses Not to Miss

Treatment

Basic Ventilator Settings

Ventilator Modes

Volume Cycled Ventilation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree