and H. Alan Crockard1

(1)

Department of Surgical Neurology, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, England

Lesions placed anterior to the neuraxis are best approached anteriorly to minimize traction and further trauma on what may well be an already compromized structure. Although this concept is applied regularly in most spinal pathology, there has been understandable reluctance to apply this principle to pathology of the clivus, craniocervical junction, and upper two cervical vertebrae. The advent of microsurgical techniques, instruments designed specifically for transoral approaches (in particular), improvements in critical care and anesthesia, and perhaps most important, modern imaging have facilitated an anterior approach.

This chapter briefly discusses the relevant anatomy, appropriate investigation, and anterior approaches in general. The majority of the discussion centers on transoral surgical techniques, the approach most frequently used for the ventral midline pathology referred to this unit.

Surgical Anatomy

A thorough knowledge of the anatomy of the craniocervical junction and its variations is vital to operative success in this area, and the reader is urged to study some of the many detailed anatomical reviews available in the literature [1 – 4].

The craniocervical junction is bounded by the ventral rim of the foramen magnum, the occipital condyles, the arch of C1, the odontoid peg, and the base of the second cervical vertebra (Fig. 4.1). At the arch of C1, the vertebral artery is 24 mm from the midline, whereas at the C2–C3 disc and the ventral rim of the foramen magnum it lies 11 mm from the midline. The distance between the foramen magnum and the base of C2 is about 40 mm and that between the lateral masses of C1 is 27 mm. The wedge-shaped clivus is 38–42 mm long, 22 mm wide, and 4 mm thick at the foramen magnum and 20 mm thick dorsal to the pituitary fossa (Fig. 4.2). Rostrally, the unprotected “knuckle” of the carotid as it leaves the petrous canal to enter the cavernous sinus is 11 mm from the midline arch of C1 (Fig. 4.3). To this are attached the longus coli muscles and the anterior longitudinal ligament. A midline raphe can be seen extending to the tubercle. Above this are attached the longus capitis and rectus capitis anterior muscles; dorsal to them lies the pharyngobasilar fascia. The vertebral arteries run about 14 mm on each side lateral to the tubercle. Deep to the bones are the tectorial membrane, the posterior longitudinal ligament, and the dura, which is often attached to the ventral rim of the foramen magnum. Within this exposure, provided that there is no rotation of C1, there are no major neural or vascular structures that cross the operative field (it should be noted, however, that venous bleeding can be encountered from the dural marginal sinus and bony diploic channels in the clivus).

Fig. 4.1

Surgical anatomy of the craniocervical junction. If there is no rotation or significant lateral mass destruction, a direct midline approach will not encounter major hazards

Fig. 4.2

Normal craniocevical junction: the clivoaxial angle is about 130 degrees

Fig. 4.3

Dissection of the craniocervical junction. The anterior arch of the atlas and most of the clivus and dura have been removed. The close relationship of the vertebrobasilar system, the lower cranial nerves, and the carotid arteries can clearly be seen

Basic Indication

Details of each surgical procedure are discussed later, but broad definitions follow. In the absence of basilar invagination, a transoral approach with elevation of the soft palate will allow access to the arch of C1 and the odontoid peg. A midline split of the soft palate will gain the access to the anterior aspect of the foramen magnum. A division of the hard and soft palate will gain access to the lower half of the clivus but has such limited lateral extension because of the upper teeth that it is now used very little. The extended “open door” maxillotomy (a combination of the Le Fort 1 osteotomy and a midline palatal split) will provide access from the sphenoid down to C3; this surgical procedure was developed in response to the challenge posed by basilar invagination. A transmandibular, transglottic approach is combined with a posterior approach for 360-degree eradicational surgery for tumors of the upper cervical spine.

Radiologic Investigations

Plain lateral films of the craniocervical junction in flexion and extension (Fig. 4.4), together with an anteroposterior view (including a good view of the peg), allow for assessment of the bony limitations of the surgical field and provide a baseline for subsequent rapid office assessment. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides exquisite soft tissue images (Fig. 4.5), but computed tomography (CT) and particularly computed myelography [5] still provide the most accurate means of identifying bony abnormalities and also provide absolute measurements of the structures involved. These methods also afford easy assessment of the craniocervical angles and the angle of the neuraxis. New software packages now allow the generation of sophisticated three-dimensional surfaces, rendering images that can be evaluated from any angle. Vertebral angiography is required to outline tumor circulation or as part of a trial vertebral artery occlusion by balloon.

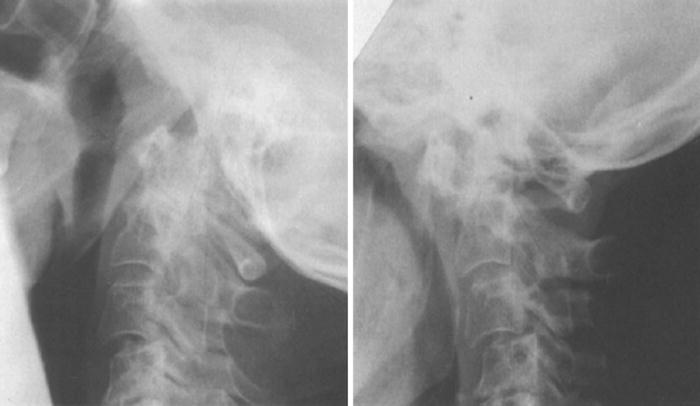

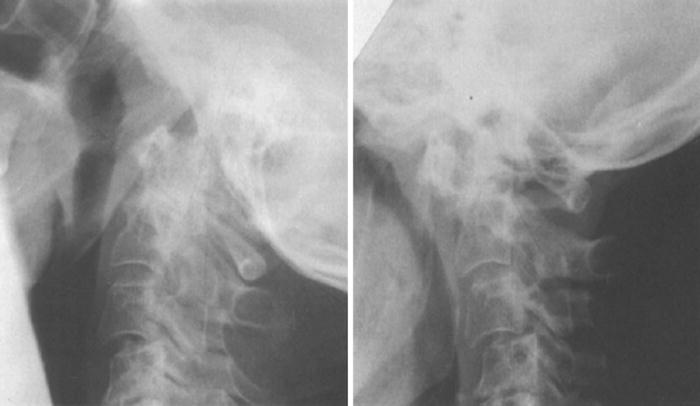

Fig. 4.4

Plain lateral radiographs of the cervical spine in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis show atlantoaxial subluxation and a step at the C2–C3 junction

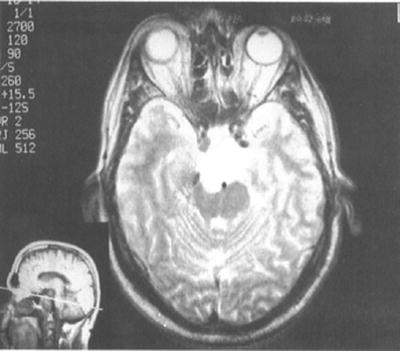

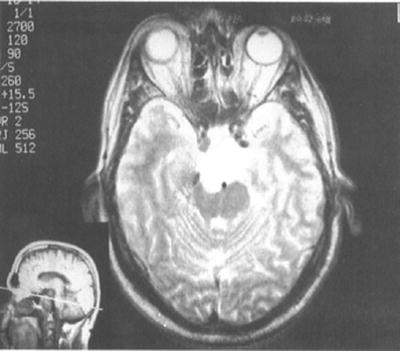

Fig. 4.5

Axial T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a skull base chordoma compressing the brainstem

Preoperative Assessment for Transoral Surgery

The Mouth

Paramount to success in transoral surgery is the careful preoperative assessment of the oral cavity and its contents. The most important of these factors is the amount of mouth opening; if the interdental distance is less than 25 mm with the patient’s mouth as wide open as possible, then a conventional transoral procedure is unlikely to be successful. In such a case, transoral surgery may be accomplished by splitting the symphysis of the mandible in the midline and laterally retracting the two parts of the mandible to allow inferior retraction of the tongue. An alternative is bilateral division of the mandibular ramus and subsequent titanium plate fixation. The patient’s dentition is a potential source of sepsis, a situation analogous to cardiac valve surgery, and a preoperative referral for dental assessment and treatment is often required, particularly in the case of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Before surgery, bacteriologic swabs of the nasal and oropharyngeal cavity are taken. Should an unusual organism be identified or postoperative infection occur, the results of these swabs are used for initial guidance. In the absence of such an event, this unit’s policy is to administer Cefuroxime and Metronidazole with the induction of anesthesia and for 48 hours postoperatively. Long-term pre- or postoperative antibiotic use increases the risk of fungal and bacterial superinfection and should be avoided. The problem posed by the edentulous patient is discussed later.

General Physical Evaluation

Many of the patients presenting for surgery have multiorgan disease (particularly those with rheumatoid arthritis), and a detailed assessment of their general condition is important. Pulmonary function may be impaired by direct pressure on the brainstem or the effects of the disease or its treatment directly on the lung parenchyma. For this reason, we routinely assess the vital capacity, arterial blood gases, and oxygen saturation of our patients. Sleep studies are often performed. In general terms, those patients with a vital capacity less than 1.2 L may have problems coming off artificial ventilation postoperatively. Cardiac and renal function also require careful assessment, and again the possible effect of the patient’s medication on these organ systems is stressed, for example, steroids and cytotoxic agents in rheumatoid arthritis.

Electrical Studies

Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) and motor evoked potentials (MEP) have been performed on some patients, but generally very large changes have not been seen in central conduction time despite marked radiologic compression and striking postoperative recovery of function. Perioperative assessment remains difficult and of more value in posterior upper cervical spine surgery.

Anesthesia

Airway

The key to success in managing the airway during and after a transoral procedure is the development of a policy that reflects local experience and best practice. Although nearly 100 % of this unit’s early transoral cases underwent a tracheostomy, this figure is now closer to 15 %. The Phoenix group consistently use an orotracheal tube [6], but our own preference is a nasotracheal airway [7]. The main objection to orotracheal intubation is not obstruction of the operative field but rather the need to remove it postoperatively because it causes extreme discomfort in the conscious patient, we remain unhappy about changing from one form of airway to another in the immediate postoperative period. With any instability of the craniocervical junction, fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation is employed in the awake patient. A tracheostomy is used only in those patients for whom long-term ventilatory problems are expected or in those for whom an extended maxillotomy is planned.

Ventilation

Tidal volume, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and end-tidal CO2 have proved to be the most immediate indices of brainstem compression. Thus, during critical anterior and posterior surgical maneuvers muscle relaxation is reversed and the patient is allowed to breathe spontaneously.

Diversion of Gastric Contents

A nasogastric tube is inserted preoperatively, first because it is easier to do so before pharyngeal surgery and second to allow emptying of the stomach in the immediate postoperative period to prevent gastric contents from soiling the wound. In the extended “open door” maxillotomy, a pharyngogastric tube has been used in place of the nasogastric tube; it is passed into the stomach in the usual way and a stab incision made into the lateral fauces to one side through which the tube is pulled. More recently, we have used a per entral gastrotomy tube (PEG) passed 2 to 3 days before the operation.

Surgery

Positioning and Instrumentation

The lateral position with the head held in a Mayfield retractor [8] confers several advantages. Blood and washings drain away from the operative site, the operator may be seated and comfortable for an exacting procedure, and it is possible to perform an anterior decompression and a posterior fixation with the patient fixed in one position, minimizing risks to the neuraxis. This position does require some “relearning” of the anatomy, and it may be advisable to evaluate any doubtful anatomy with the patient supine and the aid of needle markers. If the head can be placed in slight extension, this will make the craniocervical junction slightly more accessible in patients with complex congenital malformations or tumor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree