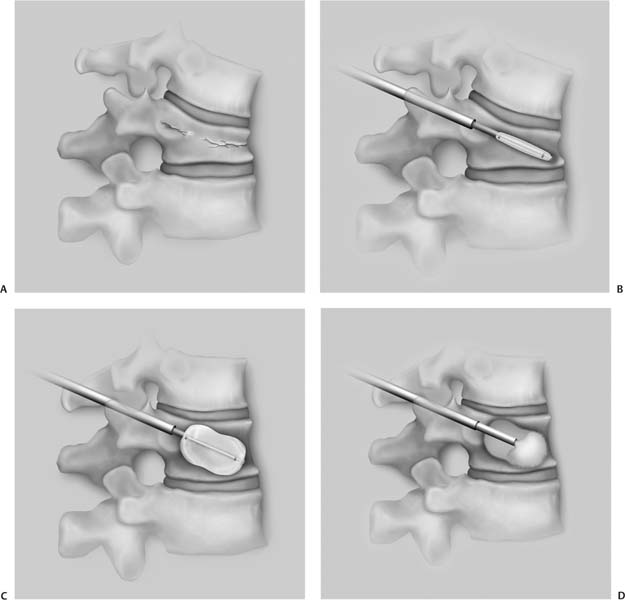

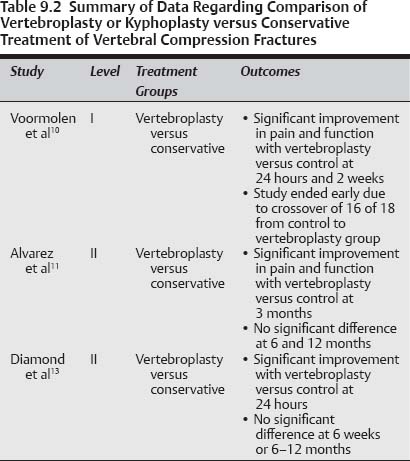

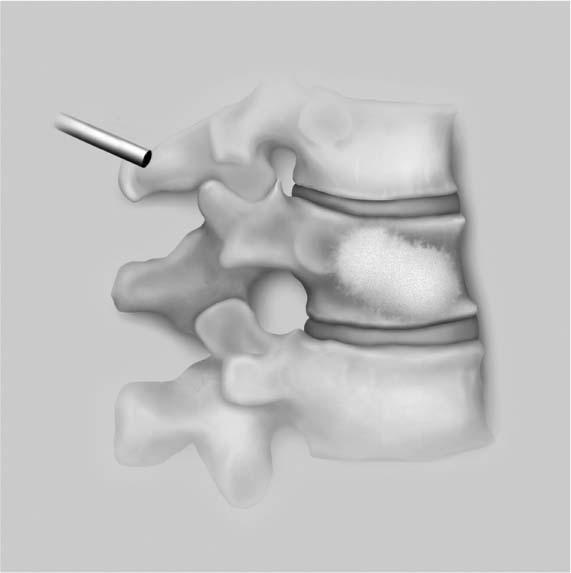

9 Osteoporosis leads to ~700,000 new vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) annually in the United States.1,2 It has been estimated that 26% of females over the age of 50 and 40% of females over 80 have sustained a VCF.1,3 The most common symptom resulting from VCF is localized pain that typically lasts for 4 to 6 weeks.4 Other potential effects include reduced pulmonary function, kyphotic deformity, and increased risk for additional VCFs.3,5,6 There has also been an increased risk of mortality following diagnosis of a VCF.7 Fortunately, for many of these patients the symptoms are self-limiting. Treatment options for these patients should include medical management of the underlying disease process, which is osteoporosis in most cases. Management of the VCF can be either conservative using a brace and analgesics or with surgical intervention. Many patients are able to tolerate the use of a brace during the healing process. This provides some symptomatic pain relief as well as protection against continued kyphotic deformity at the fracture site. For patients that can either not tolerate the use of a brace, or if they continue to experience intractable pain despite the use of the brace, surgical intervention is an option. Historically, this required the use of a traditional open procedure with an instrumented fusion.8 This approach is often not a reasonable option for these patients that are typically elderly with multiple medical comorbidities. More recently, two percutaneous techniques have been described for the treatment of VCF. Vertebroplasty was first reported by Galibert et al in 1987 for the treatment of painful vertebral hemangioma.9 In this technique needles are percutaneously placed through the pedicles into the vertebral body under fluoroscopic guidance. Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) bone cement is then injected into the vertebral body through the needles. Kyphoplasty is a modification of the vertebroplasty technique. After percutaneous placement of the needles into the vertebral body, balloons are inserted through the needles into the body. The balloons are then inflated in an attempt to create a cavity and partially restore the normal architecture of the vertebral body. Inflation of the balloons compresses the cancellous bone against the outer cortical margins. The balloons are then deflated and removed through the needles. PMMA is then injected into the cavity created by the balloons (Fig. 9.1). Although there have been numerous reports in the literature regarding vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, there are several key issues that remain somewhat controversial, including the following: (1) Is there a clinical benefit in performing vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty versus conservative treatment alone; (2) Is there an increased risk of adjacent-level VCF following vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty; and (3) Is there a clinical benefit of performing vertebroplasty versus kyphoplasty? To address these questions we have performed a comprehensive review of the literature to determine the best evidence available on each of these topics. The search included Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Registry. Additionally, a review of the references of these articles was performed for any additional studies. A search for the terms “vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty” returned 1284 articles. A search for VCF returned 2833 articles. When these were combined the search returned 613 articles. The majority of these were level IV case reports or case series, biomechanical studies, or review articles. There were three level 1 studies identified, but only one of these studies provided data on the key issues being discussed in this chapter.10 There were four relevant level II studies identified,11–14 and 23 level III studies.7,15–37 The level of evidence of the studies is summarized in Table 9.1. Fig. 9.1 Illustration of the kyphoplasty technique. (A) The patient develops a vertebral compression fracture. (B) The needle is passed through the pedicle and a balloon is inserted. (C) The balloon is inflated in the vertebral body, partially restoring the normal shape. (D) The balloon is deflated, which creates a cavity in the vertebral body, and the cement is injected. (E) The needle is then removed. There is one level I study that directly compares effects of vertebroplasty with conservative treatment. Voormolen et al performed a prospective, randomized, controlled trial to assess the short-term clinical effectiveness of vertebroplasty versus an optimal pain management control group in patients with symptomatic VCF.10 The study included 34 patients of whom 18 were randomized to the vertebroplasty group, and 16 were randomized to the control group. The initial protocol intended to follow these patients for 1 year, but the study was stopped after 2 weeks because 16 of 18 of the control patients requested to cross over from the control group to the vertebroplasty group after 2 weeks. On the first day after treatment the pain scores and analgesic usage significantly decreased in both groups. For the vertebroplasty patients the VAS scores decreased from 7.1 to 4.7, and for the control patients the VAS decreased from 7.6 to 7.1. At 2 weeks after treatment the VAS scores were 4.9 for the vertebroplasty group and 6.4 for the control group. Two patients in the vertebroplasty group sustained a new VCF during the 2-week follow-up period. One patient in the vertebroplasty group sustained a small chip fracture to the pedicle that was treated conservatively without neurological symptoms. There were no complications in the control group. When the two patients with a new VCF were eliminated from the analysis, there was a significant difference in VAS score between the two groups at the 2-week point. An interesting finding from this study was that the anal-gesic effects of vertebroplasty are immediate, and there is very little change in pain after this initial improvement. This is contrasted by the gradual improvement in pain with optimal use of analgesic medications. Table 9.1 Level of Evidence of Published Studies

Vertebral Compression Fractures: Percutaneous Vertebral Augmentation

Surgery versus Conservative Treatment

Surgery versus Conservative Treatment

Level I Data

Level | Number of Studies | Study Type |

|---|---|---|

I | 1 | Prospective, randomized, controlled trial (1 study)10 |

II | 4 | |

III | 23 | |

|

A criticism of this study is the small sample size. Due to the small number of patients in each group, confounding factors such as the new VCF have a major influence on the study results. If the data for those two patients were included, there was no difference between the two groups at the 2-week evaluation, but eliminating those two patients resulted in a statistically significant improvement in the vertebroplasty group as compared with the control group. All of the patients in the study had symptoms of VCF for between 6 weeks and 6 months. It was argued that it was difficult to recruit patients to a randomized trial that had already had a prolonged period of nonoperative care prior to the prescribed period of conservative treatment. Many patients had a preconceived notion that conservative treatment would not be effective and thus refused to participate in the study. This was further complicated by the fact that 16 of 18 patients in the control group crossed over to the vertebroplasty group after only 2 weeks.

Level II Data

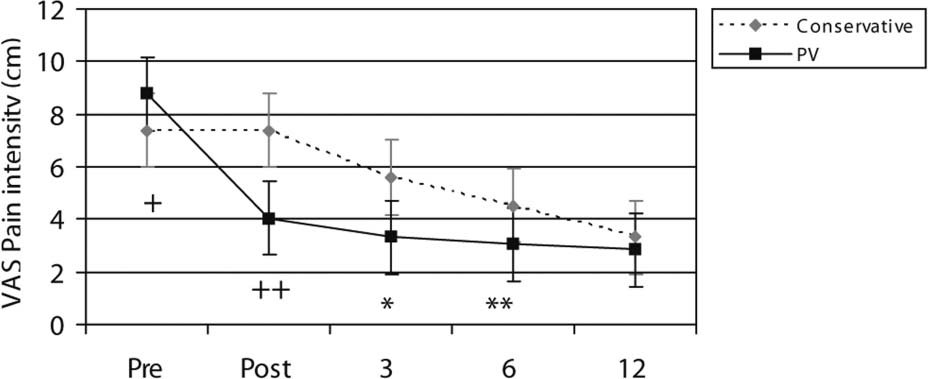

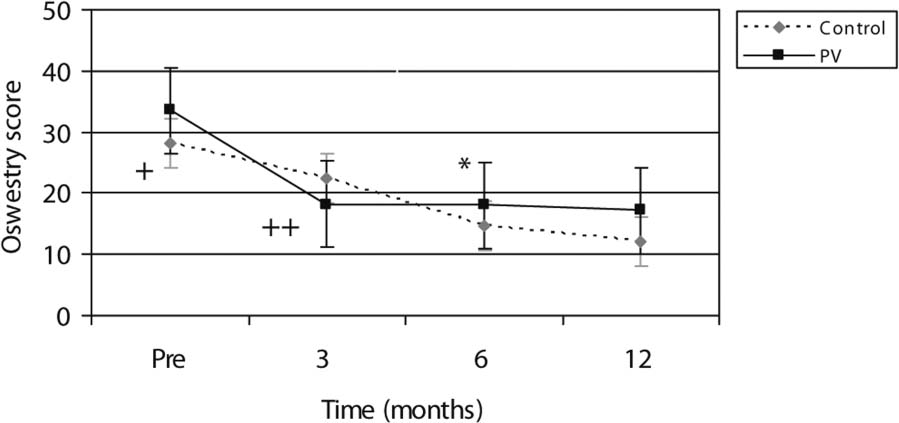

Alvarez et al reported on a prospective, double-cohort study comparing vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment for patients with symptomatic VCF.11 The study included 128 patients that had undergone conservative treatment for at least 6 weeks. Patients were enrolled in the study and given the choice of receiving vertebroplasty or continuing with conservative treatment. One hundred one patients (151 treated levels) chose the vertebroplasty treatment, and 27 continued with conservative treatment. All patients had magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence of marrow signal change to verify the presence of an acute vertebral compression fracture. Patients were excluded if the loss of vertebral height was greater than 70% or if the age of the fracture was greater than 12 months. The two groups were similar in demographics with the exception of the vertebroplasty group being significantly older than the control group (73.3 vs 69.7, p = 0.033). Patients in the vertebroplasty group reported significantly higher VAS pain scales at the initiation of the study as compared with the control patients. There was a significantly greater improvement in VAS pain scales for the vertebroplasty patients as compared with the control patients at both 3 and 6 months after treatment, but the two groups were equivalent at 12 months (Fig. 9.2). There was also a significantly greater reduction in the use of opioids in the vertebroplasty group as compared with the control group at 3 months. The Short Form-36 (SF-36) scores revealed significantly better improvements for the vertebroplasty group as compared with the control group in bodily pain (p = 0.003) at 3 months. There were no significant differences between the two groups at 6 months or 1 year. The Oswestry scores following vertebroplasty were significantly improved at each of the postoperative points compared with the preoperative levels. At 3 months the vertebroplasty group had significantly better Oswestry scores than the control group (p = 0.001). However, the control group had significantly better Oswestry scores at 6 (p = 0.006) and 12 months (p < 0.001) postoperatively (Fig. 9.3). The authors argued that this difference could be due to the fact that the control patients had significantly better health than the vertebroplasty patients at this initiation of the study. A criticism of this study was that it was not randomized. Patients were able to choose either continued conservative treatment or the vertebroplasty. Although the two groups were similar in most demographic data, the vertebroplasty group began with significantly worse symptoms than the control group. Additionally, the vertebroplasty group was much larger than the control group.

Fig. 9.2 Graph of visual analogue scale score as a function of time comparing vertebroplasty and conservative treatment. (From Alvarez L, Alcaraz M, Perez-Higueras A, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: functional improvement in patients with osteoporotic compression fractures. Spine 2006;31:1113–1118. Reprinted with permission.)

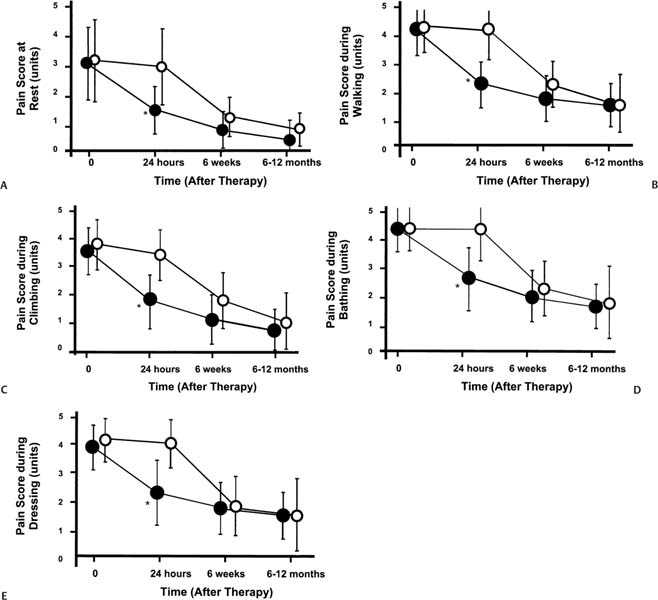

Diamond et al also reported a level II study comparing vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment for symptomatic osteoporotic VCF.13 Patients with symptoms for between 1 and 6 weeks that did not respond to nonopiate analgesia were considered for the study. Patients were given the option of receiving a vertebroplasty or continuing in a conservative treatment control group with opiate analgesics. There were 79 patients in the study, 55 (70%) of which underwent vertebroplasty, and the remaining 24 served as the control group. The two groups had similar demographic data. VAS pain scores and the Barthel index of function were recorded at 24 hours, 6 weeks, and 6–12 months after the initiation of the study. There was a significant improvement in both VAS pain score (53% improvement) and physical functioning (29% improvement) in the vertebroplasty group at 24 hours as compared with no change in the control group (p = 0.0001). Outcomes in the two groups were similar at both 6 weeks and 6 to 12 months (Fig. 9.4). There are several potential criticisms of this study. As with the study by Alvarez et al11 discussed earlier, the study was not randomized. Instead, patients were allowed to choose to either receive the vertebroplasty or continue with conservative management. Additionally, this study included patients that had failed initial conservative treatment for only 1 to 6 weeks. It is possible that with such a short initial conservative treatment period that some of the patients receiving vertebroplasty would have improved if given a longer course of conservative treatment prior to the procedure. In most cases, a period of at least 6 weeks of failed conservative treatment is recommended prior to proceeding with vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty.

Fig. 9.3 Graph of Oswestry score as a function of time comparing vertebroplasty and conservative treatment. (From Alvarez L, Alcaraz M, Perez-Higueras A, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: functional improvement in patients with osteoporotic compression fractures. Spine 2006;31:1113–1118. Reprinted with permission.)

Summary of Data

There is a limited amount of level I and II data directly comparing the outcomes of vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment of VCF. There is only one level I study and two level II studies available. There are no level I or II data comparing kyphoplasty to conservative treatment. The best evidence available suggests that vertebroplasty does provide significantly improved outcomes in terms of pain, physical functioning, and reduced need for analgesics during the short term. Given additional time, the benefits are equal to conservative treatment alone. There is some discrepancy among the studies on the duration of benefit of vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment. This can last from 2 weeks to 6 months. One potential reason for this variation is the difference in length of initial conservative treatment that was required for the various studies prior to patient enrollment.

Based on this information vertebroplasty can be recommended for patients with intractable pain related to osteo-porotic VCFs that have failed conservative treatment for at least 6 weeks. If patients are able to tolerate their symptoms, they should continue with conservative treatment alone. Based on the grading scale of Guyatt et al this recommendation would be a grade 1B: a strong recommendation, likely to apply to most patients.38 The data are summarized in Table 9.2.

Fig. 9.4 Graphs of pain score during various activities comparing vertebroplasty (solid circles) versus conservative treatment (open circles): (A) at rest, (B) during walking, (C) during climbing, (D) during bathing, (E) during dressing. (From Diamond TH, Champion B, Clark WA. Management of acute osteoporotic vertebral fractures: a nonrandomized trial comparing percutaneous vertebroplasty with conservative therapy. Am J Med 2003;114:257–265. Reprinted with permission.)

Pearls

• Level I and II evidence suggests a significant benefit for vertebroplasty for patients that have failed conservative treatment.

• There is no level I or II evidence directly comparing kyphoplasty to conservative treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree